Einar Jolin

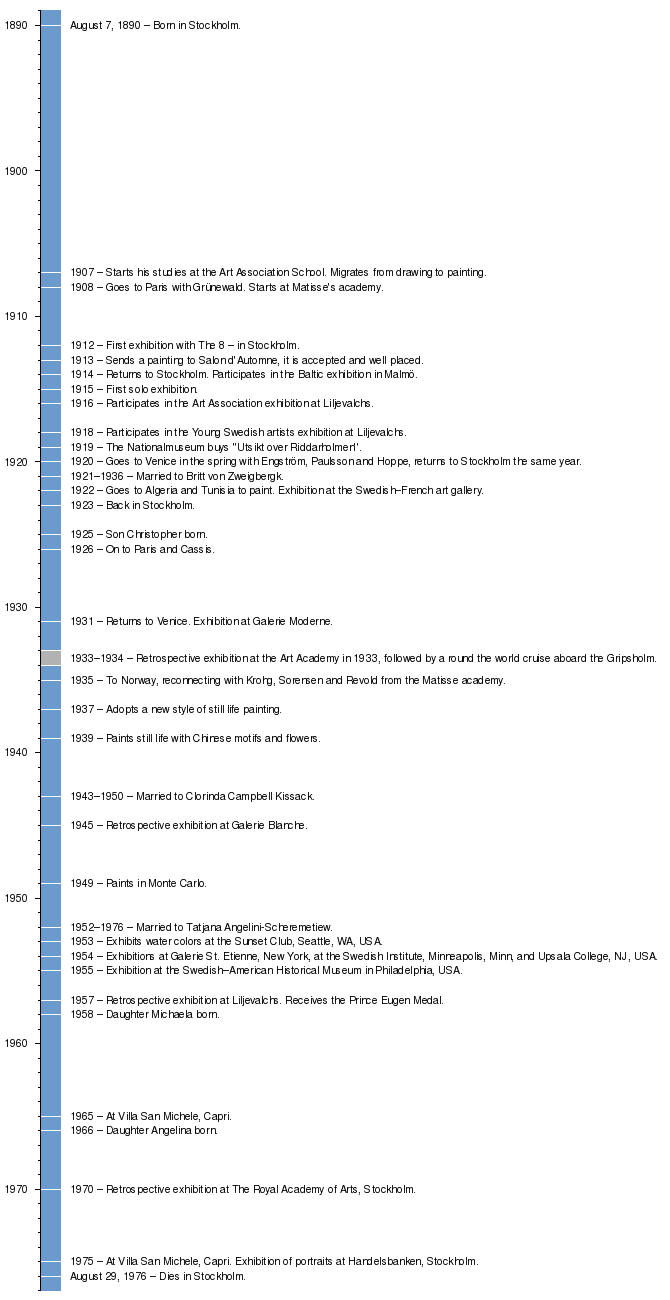

Einar Jolin (7 August 1890 – 29 August 1976) was a Swedish painter best known for his decorative and slightly naïve Expressionist style. After studying at Konstfack, Stockholm in 1906 and at the Konstnärsförbundet målarskola (the Artists Association Art School), Jolin and his friend Isaac Grünewald went to Paris for further studies at Henri Matisse's academy from 1908 to 1914.

Einar Jolin | |

|---|---|

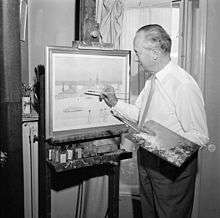

Einar Jolin at home 1960 | |

| Born | Johan Einar Jolin 7 August 1890 |

| Died | 29 August 1976 (aged 86) Stockholm, Sweden |

| Resting place | Stockholm, Sweden |

| Nationality | Swedish |

| Education | Konstfack, Stockholm and The Artists Association Art School |

| Known for | Painting |

| Movement | Expressionism |

| Spouse(s) | 1:Britt von Zweigbergk 2:Clorinda Campbell Kissack 3:Tatjana Angelini-Scheremetiew |

| Awards | Prince Eugen Medal |

He painted portraits, still lifes and cityscapes, always accentuating what he called "the beautiful" in his motifs. He mainly worked in oils and watercolors, using delicate brush strokes and light colors. His most noted works are his paintings of Stockholm during the 1910s and 1920s in his trademark naïve style.

Jolin made numerous travels, collecting impressions and inspiration for his paintings. He journeyed to Africa, India and the West Indies, but favored the countries around the Mediterranean Sea, especially the island of Capri where he also exhibited his works.

He had several exhibitions at Liljevalchs konsthall in Stockholm and in 1954, he toured the United States with an exhibition, during which Dag Hammarskjöld purchased a painting for his office in the United Nations building.

Biography

Early life and education

Einar Jolin was born 7 August 1890 in Stockholm. He was the son of professor Severin Jolin and grandson of actor Johan Christopher Jolin. He grew up on Kammakargatan 45 in the Jolinska Huset (Jolin Residence),[1] a three-story townhouse with a garden, built by his grandfather.[2][3] Jolin grew up in the middle of Stockholm close to Tegnérlunden, Adolf Fredrik Church and Vasaparken, which may have influenced his depiction of houses, roof tops, and views of Stockholm in his paintings.[4] Jolin loved his house with its exotic furnishings. For interior paintings, he often selected props from things in the house – Gustavian and Empire style furniture, Chinese embroideries and East Indian tableware.[5] Other residents in the house were his parents, brother Eric, sisters Ingrid and Signe, grandmother Mathilde Wigert-Jolin and his aunt,[4] artist Ellen Jolin (1854–1939) who was the first to teach Jolin the basic techniques of painting.[6]

Jolin's artistic education started at the Technical School (later known as Konstfack) in Stockholm in 1906. The school mainly taught painting techniques and Jolin was more interested in learning about style. Within the year, he started looking for another place to continue his studies.[7] At the beginning of the 20th century, the Konstnärsförbundet (The Artist's Association) had a school on Glasbruksgatan in Stockholm.[8] Jolin applied there in the autumn of 1907.[9] His future teacher Karl Nordström reviewed his drawings and Jolin was admitted to the school the same year.[10] Jolin joined the inner circle at the school, a group of Scandinavian artists who would later become known as De Unga (The Young Ones) or 1909 års män (The Men of 1909).[11][12][13] Among these were Isaac Grünewald, Leander Engström, Birger Simonsson and Gösta Sandels.[14] Jolin described the pupils at the school as: "... a bunch of individuals with long hair, great muffler scarves and slouch hats worn askew in a way that really impressed me since I was only seventeen and the youngest of the bunch. The most amazing of them all was of course Isaac who had longer and more raven hair than anybody else and a fluttering violet scarf. I had not yet beheld such a creature. We became good friends."[13][15] Jolin's education at the Artist's Association was curtailed by the school's closure in the spring of 1908.[16]

Paris

In 1908, Jolin and Isaac Grünewald left Sweden for the vibrant life in Paris and its art community.[17] The Swedish painter, graphic artist and forester Carl Palme knew Henri Matisse[18] and helped the artist to find a suitable location for the new Matisse Academy. An abandoned nunnery in central Paris became the first home for the academy.[19] Together with Grünewald and Leander Engström, Jolin joined the Matisse Academy, where their friends from Stockholm had already been accepted as pupils.[19][20] At the Academy, Jolin would develop his sense for a stylish line in combination with bright and clean colours in his paintings.[14][21]

Jolin's time at the Academy proved more educational for him than the schools he had previously attended and the experience he got from having an established artist as mentor, was important for his development as an artist.[22] Even so, the influence of Matisse on his young pupils should not be exaggerated. Jolin learned croquis at the academy and also developed a natural, spontaneous speed in his brushwork.[23] He mostly painted models and still life,[24] and during a visit to the south of France in 1911, he made his earliest landscapes.[25] At the school, Jolin got his first nickname; the other students, as well as Matisse, used to call him "The Puppy" since he was the youngest of the students.[20][26]

During his time in Paris, Jolin became good friends with Nils Dardel. Jolin also spent some time in Senlis where he depicted its street life 1913,[20] before returning to Stockholm the following year.[27]

Return to Stockholm

In the spring of 1914, when Jolin and his friends from the Matisse Academy returned to Stockholm,[28] the group became known as De Unga (The Young Ones). Their participation and paintings created uproar in the Baltic Exhibition in Malmö.[29] Albert Engström, artist and influential member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Arts as well as other members of the Swedish art world at that time, stated that they were perplexed and unable to understand The Young Ones' works.[30]

Jolin had planned to return to Paris the following summer, but the outbreak of World War I on 28 July 1914, forced him to reconsider his decision. With the road to France closed, he decided to stay in Stockholm,[30] and managed to obtain a studio workshop on Fiskargatan 9,[31] in the so-called "Scandalous House" [lower-alpha 1] near Katarina Church in the southern part of town.[20] From his window he had a wide view of the city, the Stockholms ström and the harbour entrance. In that apartment, during the years 1914–1915, he created some of his best-known vistas of Stockholm.[33]

In 1917, Jolin rented a studio at Kungsbroplan in Stockholm and painted diligently.[34] At the end of that year he was visited by Herman Gotthardt, a wholesaler from Malmö, who had recently taken up art collecting as a hobby.[35] He studied Jolin's numerous works and, as at this time the artists sold very few paintings, it came as a surprise to him when Gotthardt bought 16 canvases. Jolin received seven thousand crowns (sek) for the paintings, and at home the same evening he was able to show his parents the money from his first major sales, saying: "Look here, this is what I earned today".[36]

Jolin spent most of 1918 in Copenhagen,[30] where he showed his paintings at an art gallery at Nikolaiplads.[37] They sold well enough for him to stay in Denmark almost a year. Jolin enjoyed life in the Danish capital, the social life was more spontaneous than in Stockholm and people from different professions, or social standings, mixed with each other in a way that appealed to him.[38]

Travelling

After World War I, traveling was once again possible for the many young artists who had been forced to stay home during the six years of war. In 1920, Jolin went on a journey, first to Italy,[39][40] North Africa and Spain for new international impressions, and then on to India, Africa[41] and the West Indies.[42] In the spring of 1924, Jolin went to Spain with his first wife, Britt von Zweigbergk. Like many other artists he painted the bullfights,[40][43] but contrary to the strong, and sometimes bloody, bullfight painted by his colleague and close friend Gösta Adrian-Nilsson (GAN),[lower-alpha 2][45][46] Jolin's works were created in the calm and orderly manner that had earned him his second nickname: Eleganten Einar (Einar, the Elegant).[lower-alpha 3][47]

In 1931, Jolins friend, GAN moved to Bastugatan 25, and in 1936, Jolin followed his example and rented an apartment in the same building, where he lived until 1943.[48][49] At that time the street was home to numerous artists and writers.[50] The Swedish writer Ivar Lo-Johansson, who had a studio apartment at number 21, described life in the area thus: "In a part of a street, no longer than three hundred meters, everything existed. Bastugatan had become a kind of Montmartre to art, a concept."[51] In 1990, Lo-Johansson's apartment was converted into a literary museum by the Ivar Lo-Johansson Society.[52]

During the years from 1935 to 1956, Jolin spent much of his time travelling.[53] In 1954, he toured the United States with an exhibition. It was opened in January, by Swedish ambassador Erik Boheman, at Galerie St. Etienne in New York.[54] Secretary-General of the United Nations Dag Hammarskjöld, attended the exhibition and bought a painting depicting Riddarholmen for his study of the United Nations building. The exhibition was shown on national TV in the United States.[55] Jolin also exhibited his works at galleries in several other countries, and in 1957, the Liljevalchs konsthall hosted a retrospective exhibition featuring over 200 of his paintings.[13][56]

Family and later life

With the birth of his first daughter, Michaela, in 1958,[57] Jolin settled down to a more quiet life as a father and family man.[58] His second daughter Angelina was born in 1966.[59] He continued to paint, mostly still life and portraits, at his studio apartment at Stagneliusvägen 34, in Fredhäll.[60] He spent most summers with his family in Tällberg in the Dalarna County or at Villa San Michele on the island of Capri.[61] Although he held some minor exhibitions,[62] his work from the 1960s to his death in 1976, did not receive the same acclaim as his earlier paintings.[63]

Jolin married three times and had three children. His first marriage was to Britt von Zweigbergk, 1921–1936,[64] during which time they had a son, Christopher Jolin, born in 1925.[65] He was married secondly to Clorinda Campbell Kissack in the years 1943–1950,[65] and thirdly in 1952–1976 (his death) to singer Tatjana Angelini-Scheremetiew.[66] Einar Jolin died on 29 August 1976, and is buried at Norra Begravningsplatsen in Stockholm.[67]

Career

Style

Although influenced by Matisse, the Oriental art that Jolin discovered at Musée Guimet was even more important to his style. Chinese and Japanese art became the base for the decorative, slightly naïve style in light colours, that he developed during the 1910s and 1920s.[14][25] Jolin's style deviates from that of the traditional Expressionists, in that he simplifies his motifs in an almost primitive way, painting an imagined reality rather than raw emotions.[68]

Jolin, as well as Dardel, used a naïve style in their paintings before this concept had been introduced into the Swedish art world.[29] Both Jolin and Dardel were inspired by French naïvists, not just by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, but also by Séraphine Louis who lived in Sentis[69] and Wilhelm Uhde, a specialist in naïve painting. Matisse, Jolin's and Dardel's mentor, was no stranger to naïve art but it was not prominent in his work. Jolin also appreciated the cultivated and sophisticated, older painting, and was deeply impressed during his visits to the Louvre, where he was inspired by the works of masters such as Rubens, Watteau and Chardin.[22]

Expressionism

_1915.png)

In 1913 to 1914 Jolin started to paint in his own naïve interpretation of Expressionism.[70] By the end of the 1910s his works became more expressed and the shapes more plastic, but in 1916, Jolin's paintings were still inspired by the years he spent in France.[71] That spring, members of the Konstnärsförbundet (The Artists Association) and their young pupils, were invited to present the new style, Expressionism, to the Swedish audience as exhibition number two (number one being Anders Zorn, Bruno Liljefors and Carl Larsson) at the new art venue, the Liljevalchs konsthall, in Djurgården.[72] Participating in the second exhibition were a number of noted Swedish artists at that time, including Leander Engström, Isaac Grünewald, Gösta Sandels, Birger Simonsson and Jolin who exhibited thirteen paintings.[30][73]

Two so dissimilar painters and tempers as Einar Jolin and GAN were both called Expressionists.[48][74] During most of the 1910s this term was used in a number of contexts in Sweden. In 1915, the Herwarth Walden gallery Der Sturm in Berlin,[75] a venue for Expressionists, presented an exhibition, Schwedishe Expressionisten (Swedish Expressionism), with works by Swedish artists.[76] Jolin participated with six paintings, three of these were vistas from Stockholm. The rest of the participants were Isaac Grunewald, Edward Hald, GAN and Sigrid Hjertén.[75] In the autumn of 1915, Jolin and GAN held a joint exhibition in Lund University's art museum.[74][77] Despite their differences, their friendship continued during GAN's years in Stockholm (1916–1919). Jolin was tired of Isaac Grünewalds increasingly dominant role among the young Swedish artists at that time, a sentiment shared by GAN.[73] Expressionism never became a dominant style for Jolin, not in the way GAN and other members of the group embraced it. GAN always objected to Jolin's choice to include colors such as pearl gray and light purple or violet in his paintings.[78]

During the years 1925–35, Jolin's style is characterized by light, soft, grey notes and pastels.[79] Later on, still life featuring Oriental porcelain, preferably displayed on a reflecting mahogany tabletop,[80] became a more common motif.[81] He also painted numerous portraits of the Swedish socialites at that time.[1][82]

In the 1930s, Nils Palmgren, named a group of Swedish painters "The Purists",[83] an expression originally coined by the French artists Amedée Ozenfant and Le Corbusier. Palmgren referred to painters such as Torsten Jovinge, Erik Byström, Wilhelm Wik and Helge Linden. But, according to Palmgren, Einar Jolin could also be called a Purist since he constantly stressed that colors should be kept pure, contours clear and the composition of the motif orderly.[84] During his more than 70-year career, Jolin always followed his own path.[1][85] Through his motifs, characteristic portrayals, still lifes and pictures of Stockholm, an observer can follow Jolin on his journeys to other cultures, explore the collected artifacts in his house or get acquainted with what Stockholm looked like during the first part of the 1900s. Nils Palmgren ends his 1947 biography on Einar Jolin with the words:

Nils Palmgren on Jolin:

- Let us just say this: The artistic hallmark of Einar Jolin comes from his eternal worship of natures beauty, the beauty in landscapes, women, flowers and animals, fabrics and things. He is a tenderhearted, although a bit pretentious guardian of the artistic purity, the simple line, the clear spaces and the poet of soft shapes. His best human qualities are character, pride and courage to walk alone against the tide.[86]

Depicting Stockholm

Jolin started to depict Stockholm when he moved to Fiskargatan, on the tall cliffs of southern Stockholm in 1914. From his studio he could see most of the city. He divided the view, facing Stadsgården or Riddarholmen, into smaller frames for his paintings. Noted works from that time are: Strömmen mot Kastellholmen (Over the Strömmen on to the Kastellholmen) 1914, now in the Stockholm City Museum; Utsikt över Riddarholmen (View of Riddarholmen) 1914, bought by the Nationalmuseum but kept in the Moderna Museet,[87] and Utsikt mot Kastellholmen (View towards the Kastellholmen) 1915, now in the Malmö Konstmuseum.[87] In the Stockholm från Söders höjder (Stockholm from the heights of Söder) 1938, elements from Oriental art are present in the naked, branches of the trees and the red buoys looking like Chinese lanterns hanging in the trees.[1] These paintings are defined by swift, flowing brushwork and forceful contours framing fresh, light colours. His composition of the motif involved putting details against big blocks of cool pink, sheer blue, ivory turquoise and emerald, thereby creating a populated setting.[88] There is always an air of teaming citylife along the docks and busy boating on the water of the Strömmen in these paintings.[71]

Jolin was a strong advocate for the architectural and aesthetic preservation of the capital, as is written in his draft for a pamphlet called Mot strömmen (Against the Tide).[89] According to him, Stockholm had become an ugly town, by insensitive mixing of styles, densification, and centuries of eager renovation.[90][91] Jolin wanted to bring out the beautiful and the genuine in the cityscape, as well as restore, what he considered to be distorted parts of the city, to their former glory.[92] According to Palmgren, perhaps it was that dream Jolin expressed in his depictions of Stockholm.[93] At the end of the 19th century, and during some decades into the 20th century, artists depicted Stockholm in a variety of ways, each according to his own mind and individualism. Traditionalists worked side by side with Modernists, old with young, seasoned pursuers of the established view of the city and young enthusiastic individuals, such as Jolin.[94] By the middle of the 20th century, his focus shifted from the cityscape to other motifs such as chinoiserie settings,[95] but in his youth,[96] he and his friends from his years in Paris found inspiration in Stockholm and its surroundings.[33]

Einar Jolin said of his 1957 retrospective exhibition at the Liljevalchs konsthall:

- In my art I want to express what I have experienced when I have concentrated and immersed myself. There is this everyday view—man has named everything that surrounds her in life and she finds all this self evident and do not see the wonder of it. To me, art is to give form to the wonders of creation, to create beauty and harmony, to be able to lift a receptive observer from the trivial everyday life into the beautiful and fathomless in which we live. If I have succeeded in this, my life have not been in vain.[lower-alpha 4][98]

Throughout his life he continued to paint romanticized exteriors of Stockholm, whether in spring sunshine or winter haze, the city was always depicted as beautiful and unspoiled.[71] He expressed the idea that only through the emotions of an individual could nature be depicted the right way. In the magazine Konst (Art) 1913–14, he writes on False perspective and exaggerations in modern art etc. that: "Nature is wonderful, but a photo is nothing, because nature becomes wonderful only when it is seen and understood by a great human, and a great human always sees and feels something special in nature, something she wants to reproduce."[99]

Award

In 1957, Jolin received the Prince Eugen Medal[100] from His Majesty King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden.[101]

Exhibitions

Some of the exhibitions of his work during his lifetime were:[102][103]

- 1912 Salong Joël, Stockholm

- 1914 Baltic Exhibition, Malmö

- 1915 Stockholm

- 1916 Liljevalchs konsthall, Stockholm

- 1918 Liljevalchs konsthall, Stockholm

- 1918 Valand, Gothenburg

- 1918 Copenhagen, Denmark

- 1919 Liljevalchs konsthall, Stockholm

- 1922 Svensk-Franska Konstgalleriet, Stockholm

- 1931 Galerie Moderne, Stockholm

- 1933 Konstakademin, Stockholm

- 1945 Galerie Blanche, Stockholm

- 1953 Sunset Club, Seattle, USA

- 1954 Galerie St Etienne, New York, USA

- 1954 Swedish Institute, Minneapolis, USA

- 1954 Upsala College, New Jersey, USA

- 1955 Swedish-American Historical Museum, Philadelphia, USA

- 1957 Liljevalchs konsthall, Stockholm

- 1970 Royal Swedish Academy of Arts, Stockholm

- 1975 Handelsbanken, Stockholm

In 2010–2011, The Liljevalchs art venue held a commemorative exhibition showcasing some of Jolins best works.[1]

Legacy

As of 2009, Jolin's pictures continue to be popular at art auctions. At Stockholm auctioneer Bukowski's fall auction in 2009, one of Jolin's paintings sold for 2.53 million crowns (about US$390,000).[104]

Notes

- The house is very tall and obstructs the Katarina Church, which was considered scandalous at the time.[32] The house once again became noted in 2006 when The Girl Who Played with Fire by Stieg Larsson was published. In the book it is the home of character Lisbeth Salander.

- His name, Gösta Adrian-Nilsson, is very long and cumbersome to pronounce in Swedish, whereas his initials form a name easy to say and remember. He was called GAN his entire life. It is also written on his headstone.[44]

- Eleganten Einar was also used as the name of the 2010 exhibition at the Liljevalcs.[1]

- The Swedish word for "man" as in "mankind" has no gender, Jolin, and most Swedes, refer to "mankind" as "she".[97]

References

- Mårten Castenfors, 25 September 2010, "Eleganten Einar 140 målningar av Jolin, 2010–2011" [Einar the Elegant 140 paintings by Jolin] (in Swedish). Liljevalcs art venue. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- Palmgren pp. 15–29.

- "The Jolin Residence, painting, 1943". Bukowskis (in Swedish). Retrieved 7 May 2014.

- Palmgren p. 30.

- Palmgren p. 33.

- Palmgren p. 24.

- Palmgren pp. 46–50.

- Bergman, Emanuel. "Aron Gerle och hans konst" [Aron Gerle and his art]. Hembygden 1931 (in Swedish). abc.se. pp. 71–75. Archived from the original on 28 May 2010. Retrieved 10 May 2014.

- Palmgren p. 23.

- Palmgren p. 53.

- Palmgren p. 55.

- Palmgren p. 87.

- Liljevalchs Katalog p. 3.

- Liljevalchs Katalog p. 4.

- "Litografi av Einar Nerman föreställande Isaac Grünerwald och Einar Jolin" [Lithography by Einar Nerman of Isaac Grünerwald and Einar Jolin]. Periodical (in Swedish). Antikvärlden. Archived from the original on 8 May 2014. Retrieved 7 May 2014.

- Palmgren p. 59.

- Palmgren p. 67.

- Palmgren p. 72.

- Palmgren p. 75.

- "Michaela Jolin om Einar Jolin" [Michaela Jolin about Einar Jolin] (in Swedish). Stockholms Auktionsverk. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- Palmgren p. 13.

- Palmgren p. 79.

- Palmgren p. 81.

- Nerman, Einar (1938). Konturer, minnen och modeller (in Swedish). Stockholm. Retrieved 5 September 2014.

- Palmgren p. 80.

- Angelini-Jolin p 35.

- Palmgren p. 85.

- Liljevalchs Katalog p. 5.

- Palmgren p. 88.

- Liljevalchs Katalog p. 7.

- Palmgren p. 91.

- Jörgensen, Johan. "Percy säljer drömlyan" [Percy sells the dream flat]. Affärsvärlden online (in Swedish). Affärsvärlden. Retrieved 10 May 2014.

- Palmgren p. 95.

- Palmgren p. 107.

- Gotthard, Herman (1933). Herman Gotthardts konstsamling [The art collection of Herman Gotthard] (in Swedish). Malmö: John Kroon. Retrieved 5 September 2014.

- Palmgren pp. 107–108.

- Palmgren p. 109.

- Palmgren p 113.

- Palmgren p. 129.

- Liljevalchs Katalog p. 13.

- Palmgren p. 147.

- Palmgren p. 173.

- Palmgren p. 159.

- Ahlstrand, Jan Torsten (1985). GAN: Gösta Adrian-Nilsson : modernistpionjären från Lund 1884–1920 [GAN: Gösta Adrian-Nilsson :The pioneering Modernist from Lund 1884–1920] (in Swedish). Lund: Signum. ISBN 91-85330-71-X. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- "Gösta Adrian-Nilssons (GAN) efterlämnade papper" [Gösta Adrian-Nilsson's (GAN) archives] (in Swedish). Universitetsbiblioteket, Lunds universitet. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- "Tjurfäktning, målning av GAN 1928" [Bullfight, painting by GAH, 1928] (in Swedish). artvalue.com and Stockholms Auktionsverk. Archived from the original on 8 May 2014. Retrieved 7 May 2014.

- "Tjurfäktning i Madrid, målning av Einar Jolin, 1924" [Bullfight in Madrid, painting by Einar Jolin, 1924] (in Swedish). Liljevalchs. Archived from the original on 8 May 2014. Retrieved 7 May 2014.

- Jörgensen, Johan. "Där ett konstnärsväsen klingar – Om GAN" [Where the spirit of an artist sounds – About GAN]. Tidningen Kulturen online (in Swedish). Tidningen Kulturen. Retrieved 10 May 2014.

- "Husets och omgivningens historia" [The history of the house and its surroundings]. Website (in Swedish). Bostadsrättföreningen Katthuvudet 17. Retrieved 10 May 2014.

- Tjerneld, Staffan (1950–1951). "Människor på Mariaberget". Stockholmsliv: hur vi bott, arbetat och roat oss under 100 år [Life in Stockholm: how we have lived, worked and amused ourselves over a century.] (in Swedish). Stockholm: Nordstedt. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- Lo-Johansson, Ivar. "Bastugatan". essay (in Swedish). Ivar Lo-Johansson Sällskapet. Archived from the original on 21 November 2014. Retrieved 10 May 2014.

- "Ivar Lo-museet, en presentation" [The Ivar Lo Museum, a presentation]. Website about Ivar Lo-J (in Swedish). Ivar Lo-Johanssonsällskapet. Retrieved 10 May 2014.

- Angelini-Jolin pp. 55–68.

- "Past Exhibitions". Website. Galerie St. Etienne. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- Liljevalchs Katalog p. 60

- Angelini-Jolin p. 69.

- Angelini-Jolin p. 118.

- Angelini-Jolin pp. 153–164.

- Angelini-Jolin p. 146.

- Angelini-Jolin p. 139.

- Angelini-Jolin pp. 139–164.

- Angelini-Jolin pp. 158–177.

- Rubin, Birgitta. "Einar Jolin på Liljevalchs" [Einar Jolin at Liljevalchs]. www.dn.se (in Swedish). Dagens Nyheter. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- Angelini-Jolin p. 40.

- Angelini-Jolin p. 41.

- Angelini-Jolin pp. 55–59.

- Björnberg p 48.

- Palmgren pp. 160–162

- Palmgren p. 82.

- Wretholm, Eugen (1949). "Einar Jolin och det primitiva" [Einar Jolin and the primitive]. Paletten (in Swedish).

- Palmgren p. 96.

- Palmgren p. 97.

- Palmgren p. 98.

- Palmgren p. 116.

- Palmgren p. 115.

- Hubert van den Berg, ed. (2012). A cultural history of the avant-garde in the Nordic countries 1900–1925. Avant-garde critical studies, 1387–3008 ; 28. Amsterdam: Rodopi. ISBN 978-90-420-3620-8.

- "Expressionist-utställning: Gösta Adrian-Nilsson och Einar Jolin. : Lunds univ. konstmuseum" [An expressionism exhibition: Gösta Adrian-Nilsson and Einar Jolin] (in Swedish). Lund. 1915.

- Palmgren p. 167.

- Palmgren pp. 167–172.

- Palmgren p. 161.

- Liljevalchs Katalog p. 19.

- Liljevalchs Katalog p. 16.

- Blake, Jody (1999). Le tumulte noir: modernist art and popular entertainment in jazz-age Paris, 1900–1930. University Park, Pa.: Pennsylvania State University Press. p. 138. ISBN 0-271-01753-8.

- Palmgren p. 19.

- Palmgren p. 185.

- Palmgren p. 207.

- "108 works By Einar Jolin at the Moderna Museet, Stockholm and Malmö, database" (in Swedish). Moderna Museet digital data base. Archived from the original on 28 March 2014. Retrieved 7 May 2014.

- Palmgren pp. 95–96.

- Jolin, Einar (1954). "Mot strömmen" [Against the tide]. Konstrevy (in Swedish).

- Palmgren p. 206.

- Wretholm, Eugen (1950). "En blond arkitekt" [A blond architect]. Konstperspektiv (in Swedish) (1).

- Palmgren p. 205.

- Palmgren p. 196.

- Liljevalchs Katalog p. 11.

- Wretholm, Eugen (1949). "Kinesen bland dovhjortar" [The Chinaman among fallows]. Ord och Bild (in Swedish).

- Hoppe, R. (1928). "Einar Jolins konst" [The art of Einar Jolin]. Konstrevy (in Swedish).

- "Människa" [Man]. Svenska Akademiens Ordbok (in Swedish). Stockholm: Swedish Academy. 1945. pp. M1931.

- Liljevalchs Katalog p. 23.

- Konst 1913–14 [Art 1913–1914] (in Swedish). Stockholm: Bröderna Lagerström. 1911–1918. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- Sveriges Kungahus. "Prins Eugen-medaljen" [The Prince Eugen medal]. Official website (in Swedish). Sveriges Kungahus. Retrieved 10 May 2014.

- Sveriges Kungahus. "Medaljförläningar – Prins Eugen-medaljen" [Medal recipients – The Prince Eugen medal]. Official website (in Swedish). Sveriges Kungahus. Archived from the original on 3 June 2014. Retrieved 10 May 2014.

- Liljevalchs Katalog pp. 59–60.

- Palmgren.

- "Einar Jolin (1890–1976)" (in Swedish). Bukowskis. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- Bibliography

- Angelini-Jolin, Tatiana (1979). Tatiana om Einar: mina 25 år med Einar Jolin [Tatiana about Einar: my 25 years with Einar Jolin]. Stockholm: Askild & Kärnekull. ISBN 91-7008-991-4. (in Swedish)

- Björnberg, Karl-Axel (1998). Kungliga och Norra begravningsplatserna (vandringar bland berömda personers graver) [The Royal and North cemeteries (walks among the graves of famous persons)]. Södertälje: Fingraf. ISBN 978-91-88016-69-0. (in Swedish)

- Liljevalchs Katalog nr 224 (1957). Einar Jolin. Liljevalchs katalog, 0349-1137 ; 224. Stockholm: Liljevalchs hos Esselte. (in Swedish)

- Palmgren, Nils (1947). Einar Jolin. W & W konstböcker. Stockholm: Wahlström & Widstrand. (in Swedish)

Further reading

- Berg, Hubert van den, ed. (2012). A cultural history of the avant-garde in the Nordic countries 1900–1925. Amsterdam: Rodopi. ISBN 9789042036208.

- Boëthius Bertil; Hildebrand Bengt; Nilzén Göran, eds. (1918). "Svenskt biografiskt lexikon" [Swedish biographical dictionary] (in Swedish). Stockholm: Svenskt biografiskt lexikon.

- Bock-Weiss, Catherine C. (1996). Henri Matisse: a guide to research. 1424Artist resource manuals, 99-2494755-X ; 1. New York: Garland. ISBN 0-8153-0086-7.

- Dahl Torsten; Bohman Nils, eds. (1948). "Svenska män och kvinnor: biografisk uppslagsbok. 4, I-Lindner" [Swedish men and women: biographical encyclopedia.] (in Swedish). Stockholm: Bonnier.

- Jolin, Einar (1990). Öhman, Nina (ed.). Einar Jolin 1890–1976 (Moderna museet, Stockholm 17 mars – 13 maj 1990). Moderna museets utställningskatalog 0347-9196. Stockholm: Moderna museet. ISBN 91-7100-383-5. (in Swedish)

- Sahlin, Nils G., ed. (1954–1955). American Swedish Historical Foundation: The Chronicle, Winter 1954–1955. 1 (4 ed.). New York: American Swedish Historical Foundation.

- Szabad Carl, ed. (1998). "Sveriges dödbok 1968–1996 : version 1.03" [Deaths in Sweden 1968–1996] (in Swedish). Stockholm: Sveriges släktforskarförb. ISBN 91-87676-20-6.

- "Vem är det: svensk biografisk handbok. 1977" [Who is that: Swedish biographical manual. 1977] (in Swedish). Stockholm: Norstedt. 1976. ISBN 91-1-766022-X.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Einar Jolin. |

- "Einar Jolin" (in Swedish). Metropol. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- "Einar Jolin på auktion" (in Swedish). Antikvärlden. Archived from the original on 8 May 2014. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- "Examples of genuine signatures by Einar Jolin". Art signature dictionary. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- "The nude in art history — Einar Jolin". Retrieved 8 May 2014.