Edwin Taylor Pollock

Edwin Taylor Pollock (October 25, 1870 – June 4, 1943) was a career officer in the United States Navy, serving in the Spanish–American War and in World War I. He was later promoted to the rank of captain. Like many naval officers, his name was often abbreviated using initials: E. T. Pollock.

Edwin Taylor Pollock | |

|---|---|

Capt. Pollock as Superintendent of the U.S. Naval Observatory | |

| Born | October 25, 1870 Mount Gilead, Ohio |

| Died | June 4, 1943 (aged 72) Washington, D.C. |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Service/ | United States Navy |

| Years of service | 1893–1927 |

| Rank | Captain |

| Commands held | USS Virginia USS Kearsarge USS Salem USS Alabama USS Hancock USS George Washington USS Oklahoma Commandant U.S. Naval Station Tutuila Superintendent U.S. Naval Observatory |

| Battles/wars | Battle of Santiago de Cuba |

| Awards | Navy Cross |

| Other work | Military Governor of the U. S. Virgin Islands (acting) and American Samoa |

As a young ensign, Pollock served aboard USS New York during the Spanish–American War. After the war, he rose through the ranks, served on several ships, and did important research into wireless communication. In 1917, less than a week before the United States entered World War I, he won a race against a fellow officer to receive the U.S. Virgin Islands from Denmark, and served as the territory's first acting governor. During the war, he was promoted to captain and a vessel under his command transported 60,000 American soldiers to France, for which he was awarded a Navy Cross. Afterward, he was made the eighth Naval Governor of American Samoa and then the superintendent of the United States Naval Observatory, before retiring in 1927.

Early career

Originally from Mount Gilead, Ohio, Pollock attended the United States Naval Academy and, as a midshipman, was assigned to USS Lancaster and USS Monocacy.[1] He graduated with a rank of ensign in 1893.

After graduation, Pollock returned to Ohio and married Beatrice E. Law Hale on December 5.[2] Two weeks later, he was assigned to the cruiser USS New York during its initial shake-down.[3] He was subsequently assigned to the gunboat USS Machias for an expedition to China.[4] He remained in China for two and a half years as part of the Asiatic Squadron, then transferring to USS Detroit before returning home in 1897.[5] On his return home, the Spanish–American War was heating up and he was reassigned to New York, to see service in Cuba and Puerto Rico, eventually taking part in the Battle of Santiago de Cuba.[6]

In January 1900, he was promoted to lieutenant and assigned to USS Alliance.[7] Over the following year he served on USS Dolphin and USS Buffalo.[8] On board Buffalo, he returned to the Asiatic Squadron near China and was finally transferred to USS Brooklyn, the squadron's flagship.[9] He remained on board Brooklyn, until its return home in May 1902.[10] After a brief leave, Pollock was assigned to the USS Chesapeake (as the watch and division officer), a position he held for more than one year.[11] He was transferred to USS Cincinnati, serving for another year, and then to Cavite Naval Base.[12] At Cavite, he was promoted to lieutenant commander in February 1906.[13]

His first duty as a lieutenant commander was on USS Alabama, as the navigator.[14] In 1910, Pollock was reassigned to USS Massachusetts, where he was promoted to commander in March 1911.[15][16]

On his promotion, Pollock commanded USS Virginia and USS Kearsarge, before being transferred to the United States Naval Observatory.[17] During his command of Kearsarge, Pollock briefly commanded USS Salem for a world-record setting wireless experiment. For this feat, Salem was outfitted with 16 different wireless telegraph technologies and sailed to Gibraltar, with Pollock commanding. On arrival, they tested these technologies and set a world-record for longest wireless telegraph distance, 2,400 miles (3,900 km), using a "Poulsen Apparatus", based on principles by Valdemar Poulsen. Experiments were also conducted to determine wireless characteristics during inclement weather and during both the day and night.[18] In 1916, he was put in command of USS Alabama, the ship on which he had been the navigator.[19]

U.S. Virgin Islands

In the final days before the entrance of the United States into World War I, the US military was concerned that Germany was planning to purchase or seize the Danish West Indies for use as a submarine or zeppelin base.[20] At the time, Charlotte Amalie on Saint Thomas was considered the best port in the Caribbean outside of Cuba, and Coral Bay on Saint John was considered the safest harbor in the area.[21] Although the United States was not yet at war with Germany, the US signed a treaty to purchase the territory from Denmark for 25 million dollars on March 28, 1917. President Woodrow Wilson nominated James Harrison Oliver to be the first military governor.[22] The United States announced plans to build a naval base in the territory to aid in the protection of the Panama Canal.[23]

Oliver was unable to travel immediately to the Islands and the honor of being the first Acting Governor of the United States Virgin Islands was decided in an unusual way. Both Pollock, commanding USS Hancock, and B. B. Blerer's USS Olympia were dispatched to the Islands in a race. The commander of the ship that arrived first would officiate at the transfer ceremony and be acting governor.[22] Pollock arrived first and the transfer ceremony took place on March 31, 1917, on Saint Thomas. Blerer officiated at a smaller ceremony on Saint Croix. Present for the handover was the crew of the Danish station cruiser Valkyrien and the former island legislature.[24] The United States declared war on Germany on April 6, less than a week after securing the islands. Oliver was confirmed by Congress on April 20 and relieved Pollock as governor.

World War I

During the war, Pollock was appointed as captain on USS George Washington, a German cruise liner which was seized by the United States government for use as a military transport ship. She was rechristened George Washington in September 1917 and Pollock was given her command on October 1, 1917. That December, she set out with her first load of troops. During the war, Pollock successfully transported 60,000 American soldiers to France in 18 round trips.[25] In 1918, George Washington was tasked to deliver President Woodrow Wilson to the Paris Peace Conference, though Pollock would not make the trip. He was reassigned on September 29, 1918.[26]

While on board George Washington, Pollock and Chaplain Paul F. Bloomhardt edited a daily newspaper. After the war, stories from the paper were assembled and published in 1919 by J. J. Little & Ives co. as Hatchet of the United States Ship "George Washington". A short review of the work by Outlook magazine called the book "readable" and "admirably illustrated". It "abounds in clever bits of fun, queer and notable incidents, and sound and patriotic editorials."[27] After the war, he was eventually reassigned to the battleship USS Oklahoma, to serve in the Pacific fleet.[25] On November 10, 1920, Pollock was awarded a Navy Cross for his services during the war.

American Samoa

On November 30, 1921, Pollock was transferred from command of Oklahoma to become the Military Governor of American Samoa.[29] Events both personal and political had led to a previous governor, Warren Terhune's, suicide on November 3, 1920, and the appointment of Governor Waldo A. Evans to conduct a court of inquiry into the situation and to restore order. Pollock succeeded Evans, who had successfully restored the government and productivity of the islands after a period of unrest.[30] At this time, American Samoa was administered by a team of twelve officers and a governor, with a total population of approximately 8,000 people. The islands were primarily important due to the excellent harbor at Pago Pago.[31]

Beginning in 1920, a Mau movement, from the Samoan word for "opposition", was forming in American Samoa in protest of several Naval government policies, some of which had been implemented by Terhune but which were not revoked following his death, which natives (and some non-natives) found heavy-handed. The movement itself may have been inspired by a different and older Mau movement in nearby Western Samoa, against the German and then New Zealand colonial powers. Some of the initial grievances of the movement included the quality of roads in the territory, a marriage law which largely forbade natives from marrying non-natives, and a justice system which discriminated against locals in part because laws were not often available in Samoan. In addition, the United States Navy also prohibited an assembly of Samoan chiefs, whom the movement considered the real government of the territory. Surprisingly, the movement had grown to include several prominent officers of former Governor Terhune's staff, including his executive officer. It culminated in a proclamation by Samuel S. Ripley, an American Samoan from an afakasi or mixed-blood Samoan family, with large communal property in the islands, that he was the leader of a legitimate successor government to pre-1899 Samoa. Evans also met with the high chiefs and secured their assent to continued Naval government. Ripley, who had traveled to Washington to meet with Secretary of the Navy Edwin C. Denby, was not permitted by Evans to enter the port at American Samoa and returned to exile in California, where he later became the mayor of Richmond.[30]

After being appointed as governor, Pollock's continued the colonization work started by his predecessor. Prior to traveling to the territory, he met with Ripley in San Francisco, California. Although Ripley maintained that American "occupation" of Samoa was usurpation, he agreed to allow Pollock to govern unfettered and to provide him with copies of his letters. Almost immediately after arriving on the island, Pollock and Secretary of Native Affairs S. D. Hall met with representatives of the Mau, becoming the first governor to do so. Shortly afterwards, some members of the Mau disbanded, though the movement would continue in some form for another 13 years.[30]

Pollock's remaining time as governor was less eventful. While exploring Tonga in May 1923, he discovered a turtle which had been branded by Captain Cook on his expedition there in 1773. The turtle was thus known to have lived more than 150 years.[32] He was ordered home on July 26, 1923.[33]

United States Naval Observatory

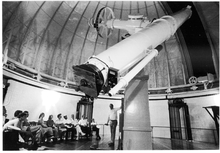

Immediately on leaving Samoa, Pollock was appointed superintendent of the United States Naval Observatory in Washington, D.C., replacing outgoing Rear Admiral William D. MacDougal.[34]

On August 22, 1924, Mars came within 34,630,000 miles (55,730,000 km) of Earth. The US Naval Observatory made no formal observations of the planet, but Pollock and the son of astronomer Asaph Hall ceremonially re-enacted Hall's 1877 discoveries of the moons Phobos and Deimos with his original 17-inch (430 mm) telescope.[35] They also made observations to calculate the masses of the two moons.[36]

On January 24, 1925, Pollock commanded the dirigible USS Los Angeles on a flight from Lakehurst, New Jersey, to photograph a solar eclipse from an altitude of 8,000 feet (2,400 m). This was the first time an eclipse had been photographed from the air.[37]

After retirement

Pollock retired from service in 1927 and was replaced as superintendent by Captain Charles F. Freeman.[38] In 1930, Pollock and his wife purchased a summer home in Jamestown, Rhode Island, while continuing to maintain their main residence in Washington, D.C. In 1932, he was made a director of the Jamestown Historical Society.[39] He also became interested in genealogy and published several works on his family's history through the 1930s.[40] He died on June 4, 1943, after a long illness and was buried in Arlington National Cemetery on June 7, 1943.[41]

Works

- Hatchet of the United States Ship "George Washington", edited by Pollock and Paul F. Bloomhardt. A compilation of stories from The Hatchet, a daily printed on board George Washington during the First World War. Published 1919.

References

- "Army and Navy". New York Times. 1891-06-03. p. 6.; "Cadets To Be Examined". New York Times. 1893-04-13. p. 3.

- Ulrich, Ron. "Edwin Taylor Pollock/Beatrice E. Law Hale". Retrieved 2007-01-22.

- "New-York's Trial Ended". New York Times. 1893-12-15. p. 3.

- "Machias Will Sail For China". New York Times. 1894-08-26. p. 5.

- "Old Salts Spin Yarns". New York Times. 1897-05-18. p. 3.

- "The United Service". New York Times. 1898-04-28. p. 3.

- "The United Service". New York Times. 1900-01-28. p. 4.

- "The United Service". New York Times. 1900-05-24. p. 5.; "The United Service". New York Times. 1900-11-21. p. 11.

- "The United Service". New York Times. 1901-03-09. p. 5.

- "The Brooklyn Home Again". New York Times. 1902-05-02. p. 3.

- "The United Service". New York Times. 1903-05-23. p. 14.

- "The United Service". New York Times. 1904-08-14. p. 13.; "Orders to Naval Officers". Washington Post. 1905-07-01. p. R8.

- "The United Service". New York Times. 1904-08-14. p. 13.; "The United Service". New York Times. 1906-02-03. p. 7.

- "The United Service". New York Times. 1906-09-12. p. 6.

- "The United Service". New York Times. 1907-05-02. p. 9.

- "United States Navy". New York Times. 1910-08-25. p. E2.

- "The United Service". New York Times. 1912-06-14. p. 21.; "The United Service". New York Times. 1913-03-27. p. 21.

- "Wireless Feat Breaks Record". Los Angeles Times. 1913-03-12. p. I5.

- "The United Service". New York Times. 1916-01-08. p. 17.

- "Virgin Island Deal Foiled Berlin Plan". Washington Post. 1917-04-10. p. 1.

- Wilfred Schoff (1916-08-18). "The Danish West Indies Ought to Pay". Los Angeles Times. p. II4.

- "Oliver to Govern Our New Islands". New York Times. 1917-03-29. p. 12.

- "Pay Danes For Island". Washington Post. 1917-04-01. p. 10.

- "U.S. Flag Over Virgin Islands". Washington Post. 1917-04-02. p. 5.

- "'Gobs' Play Hosts to Navy Officers". New York Times. 1921-06-21. p. 20.

- Edwin Taylor Pollock and Paul F. Bloomhardt, ed. (1919). The Hatchet of the United States ship "George Washington" (2nd ed.). New York: J.J. Little & Ives Co. p. 236.

- "War Books". Outlook: 581. 1919-08-13.

- "Denby Appoints Governors". New York Times. 1921-12-01. p. 24.

- Gray, J. A. C. (1960). Amerika Samoa: History Of American Samoa And Its United States Naval Administration. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute. pp. 194–210.

- Overstreet, L. M. (1922-10-18). "Always On Guard". Outlook. pp. 290–294.

- "Turtle Branded by Capt. Cook In 1773 Is Now Found Alive". New York Times. 1923-06-28. p. 1.

- "Naval Orders". New York Times. 1923-07-28. p. 19.

- "News of Army and Navy". Washington Post. 1923-09-02. p. 15.

- "Mars to be Photographed". New York Times. 1924-08-20. p. 12.

- "Army Radio Force to Listen For Signals from Martians". Washington Post. 1924-08-21. p. 9.

- "Scientists on Los Angeles Praise First Dirigible Eclipse Flight". New York Times. 1925-01-25. pp. 1–2.

- "Capt. E.T. Pollock Rites Tomorrow". Washington Post. 1943-06-06. p. M15.

- "Captain E. T. Pollock Dies In Washington". Newport Mercury And Weekly News. 1943-06-11. p. 3.

- Pitoni, Ven (1985-09-20). "What's In a Name?". Fredrick Post. p. A-7.

- Sorensen, Stan (2008-06-13). "Historical Notes, page 2" (PDF). Tapuitea Volume III, No. 24. Retrieved 2011-08-16.

External links

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Henri Konow (Acting – Final Danish Governor) |

Governor of the U.S. Virgin Islands 1917 (Acting) |

Succeeded by James Harrison Oliver |

| Preceded by Waldo A. Evans |

Governor of American Samoa 1922–1923 |

Succeeded by Edward Stanley Kellogg |