Eaton, Leicestershire

Eaton is a village and civil parish in Leicestershire, England. It is situated in the Vale of Belvoir. The population at the 2011 census (including Eastwell and

| Eaton | |

|---|---|

Saint Denys Church, Eaton | |

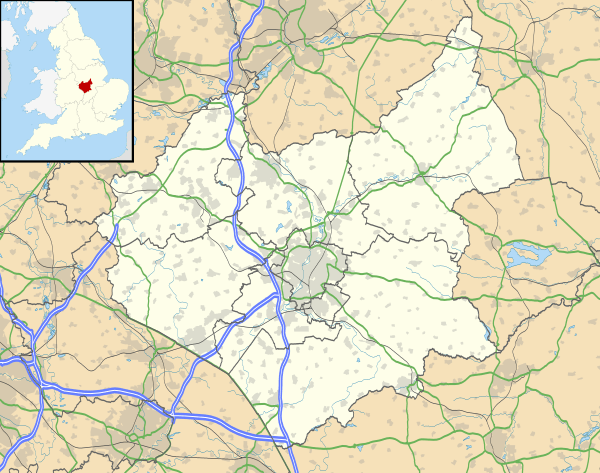

Eaton Location within Leicestershire | |

| Population | 648 (2011 Census) |

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Grantham |

| Postcode district | NG32 |

| Police | Leicestershire |

| Fire | Leicestershire |

| Ambulance | East Midlands |

| UK Parliament |

|

Goadby Marwood) was 648.[1] Eaton has a church, a village hall, a public house called "The Castle", a children's park and a new village shop. The civil parish includes nearby Eastwell, which is to the west of the village.

Nature around Eaton

The land surrounding Eaton has at least ten known springs and is the source of the River Devon. It is full of sandstone and in the past a large quarry was formed outside the village. The quarry has since become a woodland area. The land is also full of iron ore and the area was a famous source of iron, supplying two local iron works by rail via the Eaton Branch Railway from around 1884 to 1965.[2] The railway bridge under which the iron was transported is still in Eaton today.

Buildings in Eaton

The church in Eaton is Saint Denys Church, which mostly dates back to the 13th century. Unusually the spire is built of ironstone.[3] The public house in Eaton is "The Castle", which serves food and is also a registered campsite. It is also probably one of the only pubs in England to have a village shop built on the side of it. Eaton also has a village hall which was built in 1952.

Local legends

Like most ancient villages Eaton has a few local legends. Probably the most famous is the "phantom cat" which stalks the surrounding countryside at night. There have been over 300 recorded sightings of the cat, said to be a black panther, over 2001 to 2002. People believe there must be more than one cat in the area and there have been sightings of dead herons and dead lambs found in trees. There are also plenty of hiding places for the cats as there are large stretches of abandoned railway now covered in trees.

The other local story is that of "Ash Tree Operations". According to locals, back in the 17th century a band of vigilantes formed an organisation called Ash Tree Operations and built a huge underground hideout somewhere in the Eaton countryside. The entrance to this was a hollow ash tree which gave the organisation its name. The reason this band was formed was that in the 17th century Eaton was a popular haunt for criminals from the surrounding villages and there were many murders and many houses were looted.

Eaton was considered too desolate for the police to get involved so ten local men formed Ash Tree Operations and became vigilantes, doing terrible things to anyone who committed a serious crime. The legend states that whenever someone commits a serious crime in Eaton and gets away with it the site of Ash Tree Operations will be found and the finder will restart the band and "deal" with the perpetrator.

History

The incumbent's reply to the Articles of Inquiry for the Ecclesiastical Revenues Commission in 1832.

- Robert Walker, the vicar, gives the population of Eaton as 350 (from the 1831 census). He was admitted in October 1814. There was no curator so he did the duties himself. There was only one church which was capable of accommodating the entire population. The "Glebe House unfit, being a mere cottage and very damp" was occupied by Richard Palmer who rented part of the land, paying £10.4.0 for the lodgings. The annual income of the benefice was stated as £83.6.2, no tithes or corn rents or dividends and any other income. The Surplice and other fees amounted to nine or ten shillings. This was a poor living, as the incumbent states: "I expect a decrease of Income in future but cannot speak as to the amount of that decrease because the lands are said to be too high let at present and poor rates are increasing."

- Source: Articles of Inquiry. Ecclesiastical Revenues Commission: Diocese of Lincoln. Article no. 2348.

Iron Ore Quarrying

Iron ore was quarried in the parish between 1884[4] and 1965. A mineral branch, known as the Eaton Branch, was built by the Great Northern Railway in 1884[5] to transport the ore. Its terminus was to the north of the Belvoir Road. Its nearest point to the village was a bridge passing under Stathern Road. The first ore was carried to a railway wharf to the north of that bridge by a narrow-gauge tramway in horse-drawn wagons. The horses on that line were replaced by steam locomotives in 1890. The railway never had a passenger service but occasionally freight other than iron ore was carried. The first ore was dug to the west of this railway to the north of the Stathern Road close to the bridge.[6]

The quarries at the northern end of the Eaton Branch were owned by the Waltham Iron Ore Company, a subsidiary of the Staveley Coal and Iron Company. Ore was transported from these quarries to the Eaton Branch by the narrow-gauge Waltham Iron Ore Tramway, starting in 1884. One of the locomotives that worked on this tramway is preserved at the Irchester Narrow Gauge Railway Museum.[4]

More quarries were opened over the years. The quarries later surrounded the village and except as noted below they were connected with the Great Northern branch railway at various points by standard or narrow gauge tramway. One group of quarries used a tramway that connected to an aerial ropeway which ran to sidings on the railway to the south of the Stathern Road bridge. The ropeway ran from 1914 to 1916 and from 1923 (when it was rebuilt) to 1948. Tipping docks were built at the wharf and also one at the branch terminus on the Belvoir Road. A group of quarries to the south and east of the village connected with a narrow-gauge tramway running via Eastwell to the Great Northern and London and North Western Joint Railway near Harby.

The ore was dug by hand at first but from 1912 onwards steam diggers were introduced. From 1936 onwards these began to be replaced by diesel diggers. The Waltham tramway had steam locomotives from its opening in 1884. One of the tramways had a petrol locomotive from 1929 and a diesel locomotive from 1936. From 1946 onwards the tramways began to close and ore was transported from some quarries to the wharf by lorry. The last quarries to close were south of the Stathern Road and west of the railway and close to the Eastwell Road (east of the road). The last loads of ore were transported from these quarries to the railway wharf by lorry in December 1965. The Eaton Branch then closed and was lifted.

There was a wooden viaduct on the railway which was filled in with slag from Holwell Ironworks in 1955. The embankment thus made is one of the two main monuments to iron ore quarrying in Eaton, the other being the final face of a quarry close to Eaton Grange which ceased production in 1948. This had been one of the quarries which transported ore via a tramway which connected with the ropeway. Most of the quarries have been landscaped and returned to agricultural use.[6]

Eaton church

Eaton church Nature in Eaton; owl boxes

Nature in Eaton; owl boxes Eaton church again

Eaton church again One of the springs around Eaton

One of the springs around Eaton Start of the river Devon

Start of the river Devon Eaton

Eaton Eaton graveyard

Eaton graveyard Land where iron ore used to be mined

Land where iron ore used to be mined Nature in Eaton; badger sets

Nature in Eaton; badger sets "The Castle"- Eaton pub

"The Castle"- Eaton pub

References

- "Civil Parish population 2011". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- Aldworth, Colin (2012). The Nottingham and Melton Railway 1872 - 2012.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus; Williamson, Elizabeth (1984). Buildings of Leicestershire and Rutland. Buildings of England (2nd with corrections of 1992 ed.). London: Penguin. p. 149. ISBN 0-14-071018-3.

- Quine, Dan (2016). Four East Midlands Ironstone Tramways Part One: Waltham. 105. Garndolbenmaen: Narrow Gauge and Industrial Railway Modelling Review.

- Turnock, David (2016). An Historical Geography of Railways in Great Britain and Ireland. Routledge. p. 1925. ISBN 1-351958-93-3.

- Tonks, Eric (1992). The Ironstone Quarries of the Midlands Part 9: Leicestershire. Cheltenham: Runpast Publishing. p. 45–145. ISBN 1-870-754-085.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Eaton, Leicestershire. |