Early history of Gowa and Talloq

The Makassar kingdom of Gowa emerged around 1300 CE as one of many agrarian chiefdoms in the Indonesian peninsula of South Sulawesi. From the sixteenth century onward, Gowa and its coastal ally Talloq[lower-alpha 1] became the first powers to dominate most of the peninsula, following wide-ranging administrative and military reforms, including the creation of the first bureaucracy in South Sulawesi. The early history of the kingdom has been analyzed as an example of state formation.

Genealogies and archaeological evidence suggest that the Gowa dynasty was founded around 1300 in a marriage between a local woman and a chieftain of the Bajau, a nomadic maritime people. Early Gowa was a largely agrarian polity with no direct access to the coastline, whose growth was supported by a rapid increase in wet Asian rice cultivation. Talloq was founded two centuries later when a prince from Gowa fled to the coast after his defeat in a succession dispute. The coastal location of the new polity allowed it to exploit maritime trade to a greater degree than Gowa.

The early sixteenth century was a turning point in the history of both polities. Tumapaqrisiq Kallonna of Gowa conquered the coastline and forced Talloq to become Gowa's junior ally. His successor, Tunipalangga, enacted a series of reforms intended to strengthen royal authority and dominate commerce in South Sulawesi. Tunipalangga's wars of conquest were facilitated by the adoption of firearms and innovations in local weaponry which allowed Gowa's sphere of influence to reach a territorial extent unprecedented in Sulawesi history, from Minahasa to Selayar. Although the later sixteenth century witnessed setbacks to Gowa's campaign for hegemony in Sulawesi, the kingdom continued to grow in wealth and administrative complexity. The early historical period of the two kingdoms—a periodization introduced by Francis David Bulbeck and Ian Caldwell—ended around 1600 and was followed by the "early modern" period in which Gowa and Talloq converted to Islam, defeated their rivals in South Sulawesi and expanded beyond South Sulawesi to become the most important powers in eastern Indonesia.

The early history of Gowa and Talloq witnessed significant demographic and cultural changes. Verdant forests were cleared to make way for rice paddies. The population may have grown by as much as tenfold between the thirteenth and sixteenth centuries, while new types of crops, clothes, and furniture were introduced into daily life. The scope of these territorial, administrative, and demographic transformations have led many scholars to conclude that Gowa underwent a transformation from a complex chiefdom to a state society in the sixteenth century, although this is not a unanimously held position.

Background

Four main ethnic groups inhabit the Indonesian peninsula of South Sulawesi: the Mandar on the northwestern coast, the Toraja in the northern mountains, the Bugis in the lowlands and the hills south of the Mandarese and Toraja homelands, and the Makassar throughout the coast and mountains in the south.[3] Each group speaks its own language, which is further subdivided into dialects, and all four languages are members of the South Sulawesi subgroup of the Austronesian language family widely spoken throughout Southeast Asia.[3] By the early thirteenth century, the communities in South Sulawesi formed chiefdoms or small kingdoms based on swidden agriculture, whose boundaries were set by linguistic and dialectal areas.[4][5]

Despite limited influence from the Javanese empire of Majapahit on certain coastal kingdoms[6][7] and the introduction of an Indic script in the 15th century,[8] the development of early civilization in South Sulawesi appears to have been, in the words of historian Ian Caldwell, "largely unconnected to foreign technologies and ideas."[9] Like Philippine chiefdoms[10] and Polynesian societies,[11] pre-Islamic Gowa and its neighbors were based "on indigenous, 'Austronesian' categories of social and political thought" and can be contrasted with other Indonesian societies with extensive Indian cultural influence.[12][13]

Historical sources

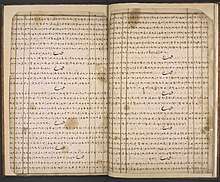

The most important historical sources for precolonial Makassar are the chronicles or patturioloang of Gowa and Talloq,[14] dated to the sixteenth century onwards.[15] The Gowa Chronicle and the Talloq Chronicle are written primarily to describe the rulers of both communities, but at the same time they contain a general description of the development of Gowa and Talloq, from the origin of the dynasties to their unification and transformation to become the most important powers in eastern Indonesia in the early seventeenth century.[14] Historians of Indonesia have described these chronicles as "sober" and "factual" when compared to babad, their counterpart from Java in western Indonesia.[16][17] The South Sulawesi chronicles centered around the reigning monarchs, and each monarch's section is arranged thematically and is not necessarily chronological.[18]

There is another genre of Makassar historical writing called lontaraq bilang, translated variously as "royal diaries" or "annals".[19][20] These annals are dated according to both Islamic and Christian calendars, with the names of the months derived from Portuguese, making it likely that the tradition of writing annals was itself borrowed from the Europeans.[19][21] Manuscripts in this genre are arranged chronologically, listing important events such as births and deaths of aristocrats, wars, construction projects, the arrival of foreign delegations, natural disasters, and peculiar events such as eclipses and the passing of comets.[22] The tradition of writing annals seems to have been firmly established by the 1630s; entries from earlier period were limited in terms of frequency and topics.[19][21]

There are hardly any external records on South Sulawesi prior to the early 16th century, save for sporadic information such as South Sulawesi place names listed in the 14th-century Javanese poem Nagarakretagama.[23] Tomé Pires's account from early 1500 provided a rather confusing description of a "big country with many islands" that he calls "Macaçar".[24] Other reports from the 16th and 17th century were limited in their geographical scope. Only after the rise of Gowa and Talloq in the early 17th century did documentation by external sources regarding the region became more coherent and detailed.[23]

Origin of Gowa and Talloq

Major dynasties in South Sulawesi associate their origins with the tumanurung, a race of divine white-blooded beings who appeared mysteriously to marry mortal lords and rule over mankind.[26] Gowa is no exception. The Gowa Chronicle specifies that the parents of the first karaeng (ruler) of Gowa were the stranger king[27] Karaeng Bayo and a female tumanurung who descended to the Kale Gowa area upon the request of the local chiefs.[28] The polity of Gowa was born when the chieftains known as the Bate Salapang (lit. Nine Banners) swore allegiance to Karaeng Bayo and the tumanurung in return for their recognition of the Bate Salapang's traditional rights.[27]

The tumanurung legend is generally viewed by archaeologists (such as Francis David Bulbeck) as a mythologized interpretation of a historical event, the marriage of a Bajau potentate with a local aristocratic woman whose descendants then became the royal dynasty of Gowa.[29][30] At the time, the Bajau, a nomadic maritime people, may have been a key trading community who transported goods from the Sulu Sea to South Sulawesi.[31] Estimates based on dynastic genealogies suggest that the founding of the Gowa polity occurred around 1300.[32] This is supported by archaeological evidence suggesting the emergence of a powerful elite in the Kale Gowa area around this time, including a large number of foreign ceramic imports.[33][34]

The founding of Gowa, circa 1300, was part of a dramatic shift in South Sulawesi society which ushered in what Bulbeck and Caldwell (2000) refer to as the "Early Historical Period".[35] Commerce with the rest of the archipelago increased throughout the peninsula, raising demand for South Sulawesi rice and encouraging political centralization and intensification of rice agriculture.[36] Population densities rose rapidly as slash-and-burn agriculture was replaced by intensive wet rice cultivation dependent on the newly introduced stock-handle plow (drawn by buffaloes[37]), with a large number of new settlements founded in the increasingly deforested interior of the peninsula.[38] Increasing rice cultivation allowed the formerly rare delicacy to displace older crops such as sago or Job's tears[38] and become the staple food of South Sulawesi.[39] These changes were accompanied by the rise of new polities based on wet rice agriculture in the interior, such as the Bugis polities of Boné and Wajoq.[38] Early Gowa, too, was an interior agricultural chiefdom centered on rice cultivation.[34]

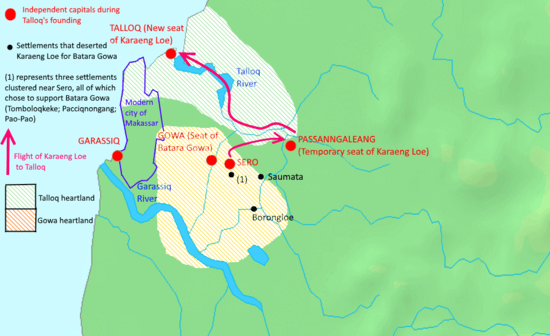

Makassar sources recount that Talloq was founded as an offshoot of the Gowa dynasty at the end of the 15th century. During a succession dispute between the two sons of the sixth karaeng of Gowa, Batara Gowa and Karaeng Loe ri Sero,[lower-alpha 2] the former seized his brother's lands[41] and, according to the Talloq Chronicle, Karaeng Loe left for 'Jawa',[42] perhaps referring to the north coast of Java[43] or to Malay commercial communities in coastal Sulawesi or Borneo.[lower-alpha 3][42] This incident may have been part of a wider process in which the karaeng of Gowa's direct authority expanded to the detriment of his independent or autonomous neighbors.[44] Upon his return, Karaeng Loe found that some of his nobles had remained loyal to him. With these followers he spent some time in a temporary seat to the east, then sailed to the mouth of the Talloq River where uninhabited forest was cleared and the new polity of Talloq was established.[41] The broad outlines of the story are archaeologically supported by a marked increase in ceramics near the mouth of the Talloq around 1500.[44]

Talloq was a maritime state from its beginnings, capitalizing on the rising quantity of trade in the region[45] and a corresponding coastal population increase.[34] Portuguese accounts suggest the existence of a Malay community in western South Sulawesi from around 1490,[46] while one Malay source claims that a sayyid (descendant of the prophet Muhammad) arrived in South Sulawesi as early as 1452.[lower-alpha 4] Karaeng Loe's son and successor, Tunilabu ri Suriwa, according to the Talloq Chronicle, "went over to Melaka, then straight eastwards to Banda. For three years he journeyed, then returned."[lower-alpha 5][42] Tunilabu's wives, including a Javanese woman from Surabaya, were also affiliated with mercantile communities. The third Karaeng Talloq, Tunipasuruq, again voyaged to Melaka and lent money in Johor.[42][49] Talloq's commercial heritage would contribute to the city of Makassar's future emergence as a great center of trade.[50]

Gowa and Talloq from 1511 to 1565

Reign of Tumapaqrisiq Kallonna (c. 1511–1546)

Older historiography, such as the work of Christian Pelras in 1977, has generally taken the view that the kingdom of Siang dominated western South Sulawesi prior to the emergence of Gowa as a major power.[51][52][53] This interpretation points to a 1544 account by the Portuguese merchant António de Paiva which seems to imply that Gowa was a vassal of Siang: "I arrived in the aforesaid port, a large city called Gowa, which formerly had belonged to a vassal of the king of Siang but had been taken from him."[54] However, Gowa's heartland is interior farmland, not a port. Bulbeck interprets Paiva's "Gowa" as referring to the coastal port of Garassiq, then contested between Siang and Gowa.[55] Recent archaeological work also yields little evidence of a powerful Siang.[46] The more modern theory suggests that there was no single overlord across western South Sulawesi until the rise of Gowa.[55]

This status quo was broken by Tumapaqrisiq Kallonna (r. c. 1511–1546[lower-alpha 6]), son of Batara Gowa, who is the first karaeng described in detail by the Gowa Chronicle.[42] Since the days of Batara Gowa, Gowa had had ambitions to annex the affluent port-polity of Garassiq, site of the modern city of Makassar,[43] but it was not until the era of Tumapaqrisiq Kallonna that this was accomplished. Gowa's conquest of Garassiq occurred possibly as early as 1511[lower-alpha 7] and provided the hitherto landlocked polity with much greater access to maritime commerce.[61] Besides Garassiq, the Gowa Chronicle credits Tumapaqrisiq Kallonna with conquering, making vassals of, or levying indemnities from thirteen other Makassar states.[62] Most of his conquests appear to have been limited to the southwestern, ethnically Makassar areas of the peninsula.[lower-alpha 8][63] Gowa may have encountered setbacks from around 1520 to 1540, such as the loss of the upper Talloq River[64] and Garassiq, but these were temporary. By the 1530s, Garassiq had been reconquered and eventually became the seat of the Gowa court,[61] with the royal citadel of Somba Opu possibly first constructed during Tumapaqrisiq Kallonna's reign.[65] Trade in Gowa expanded substantially, partly due to the decline of Majapahit in Java during the fifteenth century and the fall of Malacca to the Portuguese in 1511.[66] The former event shifted the main source of trade in South Sulawesi from Java to western Indonesia and the Malay peninsula, and the latter caused the predominantly Muslim traders from those regions to avoid Malacca and seek other ports such as Gowa.[66]

The most celebrated of Tumapaqrisiq Kallonna's accomplishments may be his war against Talloq and its allies, a crucial turning point in the history of both kingdoms[67] which occurred in the late 1530s or early 1540s.[57][68] The cause of war between Gowa and Talloq was not explicitly recorded, but a later text in the Gowa Chronicle hinted that war broke out after a Gowa prince abducted a Talloq princess.[69] Tunipasuruq of Talloq allied with the rulers of two nearby polities, Polombangkeng and Maros,[lower-alpha 9] to attack his cousin Tumapaqrisiq Kallonna.[67] Under the leadership of Tumapaqrisiq Kallonna and his two sons,[lower-alpha 10] Gowa routed Talloq and its allies in the war. As the victor, Tumapaqrisiq Kallonna was then invited to Talloq where oaths were sworn making Talloq a favored junior ally of Gowa. "The ruler of Gowa was thus publicly acknowledged as the dominant figure in the Makassarese heartlands."[67] This alliance was cemented by the large number of Talloq royal women who married Gowa kings.[67][72] Similar arrangements with Maros and, to a lesser extent, Polombangkeng ensured that the new kingdom of Gowa would command both the commercial clout of Talloq[73] and the manpower and agricultural resources of not only Gowa proper, but Maros and Polombangkeng as well.[74]

Tumapaqrisiq Kallonna's reign was also associated with internal reforms, including the expansion of historical writing and the invention of the first bureaucratic post of sabannaraq or harbormaster.[75] The first sabannaraq, Daeng Pamatteq, had a wide range of responsibilities including the maintenance of commerce in the port of Garassiq/Makassar and command over the Bate Salapang.[75] The expansion of the bureaucracy to incorporate multiple specialized positions was an innovation of the next karaeng, Tunipalangga.[62] Besides being the first important bureaucrat in Gowa's history, Daeng Pamatteq introduced historical writing to the kingdom.[76] The Gowa Chronicle credits Tumapaqsiriq Kallonna as well with making "written laws, written declarations of war".[62] Similarly, the Talloq Chronicle states that Tunipasuruq, Tumapaqrisiq Kallonna's contemporary, was the first karaeng of Talloq to excel at writing.[77] Earthen walls were also built around Kale Gowa,[78] and possibly Somba Opu in Garassiq as well.[79]

Reign of Tunipalangga (c. 1546–1565)

The reign of the next Karaeng Gowa, Tunipalangga (r. c. 1546–1565[lower-alpha 11]), was marked by military expansionism. The karaeng himself was considered to be "very crafty in war [...] a very brave person".[82] The Gowa Chronicle narrates that the karaeng was responsible for "mak[ing] smaller the long shields [and] shorten[ing] spear shafts",[82] which would have made these traditional weapons more maneuverable.[83] Tunipalangga also first introduced many advanced foreign military technologies such as gunpowder, "great cannons", brick fortifications (including Somba Opu fortress in the city of Makassar, which became the seat of government under Tunipalangga[84]), and the "Palembang bullet" used for long-barreled firearms.[82] Gowa was thus able to vanquish a large number of polities throughout the island of Sulawesi, from the northern Minahasa Peninsula to Selayar Island off the southern coast.[81] In particular, the conquest of the Bugis kingdoms of the Ajatappareng eliminated Gowa's last rivals on the west coast of Sulawesi and allowed Tunipalangga's authority to expand into their former sphere of influence in Central Sulawesi as far north as Toli-Toli.[85]

The defeated rulers were obliged to make annual pilgrimages to Tunipalangga's court in Gowa to deliver tribute and renew their ritual demonstration of submission and loyalty,[86] while marriage to local subjugated dynasties legitimized the authority of Gowa.[87] By 1565 only the most powerful Bugis kingdom, Boné, remained independent of Gowa's sphere of influence in South Sulawesi.[81] Tunipalangga not only forced the submission of most of his neighbors, but also enslaved and relocated entire populations to build irrigation networks and fortifications.[88][89]

The conquests may have involved the relocation of Malay merchants active in South Sulawesi to the Gowa-controlled port of Garassiq/Makassar,[90] although this is contested by Stephen C. Druce.[91] In any case, Malay trade in Makassar developed greatly in the mid-16th century. In order to maintain their commerce in Makassar, in 1561 Tunipalangga signed a pact with Datuk Maharaja Bonang,[lower-alpha 12] a leader of Malay, Cham, and Minangkabau merchants.[93] Bonang and his people were granted the right to settle in Makassar and freedom from Makassar customary law.[94][95] This ensured that the Malay presence in Makassar would no longer be seasonal and temporary, but a permanent community.[96] Tunipalangga's conquest of competing ports and shipbuilding centers in the peninsula, such as Bantaeng,[97] and his economic reforms, such as the standardization of weights and measures—which may have been suggested by the Malay community—also facilitated Gowa-Talloq's strategy to make itself the preeminent entrepot for eastern Indonesian spices and woods.[98]

.jpg)

The incipient Gowa bureaucracy was greatly expanded by Tunipalangga. He relieved the sabannaraq of his non-commercial duties[99] by creating the new post of tumailalang,[lower-alpha 13] a minister of the interior[100] who mediated between the karaeng and the nobles of the Bate Salapang.[101] The former sabannaraq Daeng Pametteq was promoted to become the first tumailalang.[94] Another bureaucratic innovation was the creation of the post or posts[lower-alpha 14] of guildmaster or tumakkajananngang, who supervised the operation of craftsmen's guilds in Makassar and ensured that each guild would yield the services that the state demanded of them.[102][106] In tandem with these bureaucratic reforms, centralization continued apace with Tunipalangga remembered as the first to impose heavy corvée duties on his subjects.[94] However, corvée workers continued to be recruited by the landed nobility rather than the emerging bureaucracy.[107]

Gowa and Talloq from 1565 to 1593

War against Boné and the reign of Tunijalloq and Tumamenang ri Makkoayang (1565–1582)

In the early 16th century, the Bugis kingdom of Boné had been an ally of Gowa, with the latter sending troops east to help Boné's war against its neighbor Wajoq.[108] But concurrently with Tunipalangga's foreign campaigns, La Tenrirawe, the arung (ruler) of Boné, endeavored to expand his own realm across eastern South Sulawesi. The two polities soon came to compete for the lucrative trading routes off the southern coast of the peninsula, and in 1562 war broke out when La Tenrirawe incited three of the newly acquired vassals of Gowa to ally with Boné.[109] Tunipalangga quickly forced Boné to return the three polities in question. He continued the war in 1563, leading an alliance between Gowa and Boné's principal neighbors to attack Boné from the north.[109] However, the result was a Gowa defeat where Tunipalangga was wounded. The karaeng invaded Boné once more in 1565, but returned after a week and soon died of illness.[110] The war against Boné was continued by his brother and successor Tunibatta, but Tunibatta's troops were routed within a few days.[111] The karaeng himself was captured and beheaded.[110]

Tunibatta's death was followed by a succession dispute which was resolved by Tumamenang ri Makkoayang, the Karaeng Talloq. He made himself the first tumabicara-butta or chancellor,[112] the last and most important Gowa bureaucratic post to be established. The tumabicara-butta was the principal adviser to the throne of Gowa and supervised defense, diplomacy, and royal education.[113] With his newfound authority, Tumamenang ri Makkoayang installed Tunibatta's son Tunijalloq as Karaeng Gowa. For the first time, the karaeng of Gowa shared his authority with the karaeng of Talloq.[112] Makassar chronicles note that the two karaengs "ruled jointly", while Tumamenang ri Makkoayang is recorded to have said that Gowa and Talloq had "only one people, but two karaengs" and wished "[d]eath to those who dream or speak of making Gowa and Talloq quarrel".[lower-alpha 15][115][116] This precedent would enable Karaeng Matoaya, son of Tumamenang ri Makkoayang, to later become the most powerful man in Gowa and South Sulawesi.[117]

Tumamenang ri Makkoayang's choice of Tunijalloq as Karaeng Gowa may have involved the prince's close ties to the court of Boné;[112] Tunijalloq had lived there for two years and had even fought wars on the side of Boné.[110][118] Tumamenang ri Makkoayang, Tunijalloq, and La Tenrirawe soon negotiated the Treaty of Caleppa, ending the war between Gowa and Boné. The treaty obliged Boné to grant rights to the people of Gowa within its realm, and vice versa. The borders of Boné were also clarified, with both Gowa and Luwuq (one of Gowa's allies) making territorial concessions.[109][110] This arrangement, though unfavourable to Gowa, brought peace to South Sulawesi for sixteen years.[119]

Tunijalloq and Tumamenang ri Makkoayang continued to encourage foreign commerce in Makassar. The two karaengs established alliances with and sent envoys to states and cities across the archipelago, including Johor, Malacca, Pahang, Patani, Banjarmasin, Mataram, Balambangan, and Maluku.[121][122] Trade thrived as Makassar was more fully integrated into the Muslim commercial routes, which Christian Pelras (1994) refers to as the "Champa-Patani-Aceh-Minangkabau-Banjarmasin-Demak-Giri-Ternate network",[123] and Tunijalloq had the Katangka Mosque built for the burgeoning Malay community of Makassar.[120] The influence of Islam on Gowa and Talloq grew stronger, although Muslim missionaries such as Dato ri Bandang still had little success;[124] the veneration of the divine origins of nobility and the influential role of the bissu priesthood remained powerful obstacles for Islamization.[125] In 1580, Sultan Babullah of the Malukan sultanate of Ternate offered an alliance on the condition that Tunijalloq convert to Islam, but this was rejected perhaps in order to prevent Ternaten religious influence over South Sulawesi.[126] Four Franciscans were also sent to Gowa in the 1580s, but their mission, too, was short-lived.[127] Nevertheless, foreign religions came to exert growing influence over the Gowa nobility in these years, culminating in the conversion of the kingdom to Islam in the first decade of the 1600s.[128] Other internal reforms under Tunijalloq included the expansion of court writing, the introduction of kris-making, and military strengthening such as the deployment of additional cannons in forts.[129][130]

War against the Tellumpocco and the reign of Tunipasuluq (1582–1593)

Boné felt threatened by the continuing rise of Gowa, while two neighboring vassals of Gowa, Soppéng and Wajoq, had also been alienated from their overlord due to its harsh rule.[131] In 1582, Boné, Wajoq, and Soppéng signed the Treaty of Timurung which defined the relationship between the three polities as an alliance of brothers, with Boné considered the eldest brother.[126] This Boné-led alliance, called the Tellumpocco (lit. "Three Powers" or "Three Summits"), sought to regain the autonomy of these Bugis kingdoms and halt Gowa's easward expansionism.[126][131][132] Gowa was provoked by this alliance and launched a series of offensives to the east (often with the aid of Luwuq, another Bugis polity[131]), beginning with an attack on Wajoq in 1583 which was repulsed by the Tellumpocco.[126] Two subsequent campaigns in 1585 and 1588 against Boné were equally unsuccessful.[126] Meanwhile, the Tellumpocco attempted to forge a pan-Bugis front against Gowa by forming marriage alliances with the Bugis polities of Ajatappareng.[132] Tunijalloq decided to attack Wajoq once more in 1590, but was assassinated by one of his subjects in an amok attack while leading a fleet off the west coast of South Sulawesi.[131] In 1591, the Treaty of Caleppa was renewed and peace resumed.[126] The Tellumpocco had successfully thwarted the ambitions of Gowa.

Major changes in the political landscape were also occurring in the ethnically Makassar heartlands. Tumamenang ri Makkoayang died in 1577[133] and was succeeded by Karaeng Baine, his daughter and the wife of Tunijalloq.[134] The Talloq Chronicle states that Tunijalloq and Karaeng Baine ruled both Gowa and Talloq together,[134] although Karaeng Baine appears to have obeyed her husband's wishes[135] and accomplished little of note except for innovations in handicrafts.[136] After the murder of Tunijalloq in 1590, Karaeng Matoaya, the eighteen-year-old son of Tumamenang ri Makkoayang and the half-brother of Karaeng Baine,[137] was invested with the position of tumabicara-butta. Karaeng Matoaya then appointed Tunipasuluq, Tunijalloq's fifteen-year-old son, as the new karaeng of Gowa.[136] However, besides reigning as the karaeng of Gowa, Tunipasuluq also claimed the position of the karaeng of Talloq[lower-alpha 16][138] and assumed the throne of nearby Maros upon the death of its ruler.[139] This constituted the largest realm that would ever be directly controlled by Gowa.[140] Confident of his position, Tunipasuluq sought to centralize all power in his own hands.[138][141][142] He moved the seat of government to Somba Opu[142] and confiscated the properties of, exiled, or executed aristocrats in order to weaken their resistance to his prerogative.[143][138] Many among the nobility and the Malay community fled Makassar, fearing Tunipasuluq's arbitrary rule.[138]

Tunipasuluq was overthrown in 1593 in a palace revolution most likely led by Karaeng Matoaya, the very man who had enabled Tunipasuluq's coronation.[144] The erstwhile Karaeng Gowa was exiled and died in the distant island of Buton in 1617, although he may have continued to maintain close ties with his supporters in Makassar.[145] Karaeng Matoaya was enthroned as Karaeng Talloq and appointed the seven-year-old prince I Manngarangi (later Sultan Ala'uddin), as Karaeng Gowa.[146] Maros regained its own independent karaeng after a few years of interregnum.[147] The ousting of Tunipasuluq thus secured the autonomy of the nobility, delineated the limits of the karaeng of Gowa's authority, and restored balance between Gowa, Talloq, and other Makassar polities.[138] Henceforth the dominion of Gowa was ruled by a confederation of powerful dynasties of which the Gowa royalty was nominally primus inter pares, although Talloq, the homeland of the tumabicara-butta, was often the de facto dominant polity.[148] During the following four decades, Karaeng Matoaya spearheaded both the conversion of South Sulawesi to Islam and Gowa-Talloq's rapid expansionism east to Maluku and south to the Lesser Sunda Islands.[149] The ousting of Tunipasuluq and the beginning of Karaeng Matoaya's effective rule may therefore be considered to mark the end of Gowa's initial expansion and the beginning of another era of Makassar history.[150][151]

Aftermath

According to Bulbeck and Caldwell, the turn of the seventeenth century marked the end of "early historical period" for Gowa and Talloq and the start of the "early modern" period.[152] During the early modern period, Gowa and Talloq embraced Islam, initiated by Karaeng Matoaya who converted in 1605, followed by I Manngarangi (now Sultan Ala'uddin) and their Makassarese subjects in the following two years.[153] Subsequently, Gowa won a series of victories against her neighbors, including Soppéng, Wajoq, and Boné, and became the first power to dominate the South Sulawesi peninsula.[154][155] By 1630, Gowa's expansion extended not only to most of Sulawesi, but also overseas to parts of eastern Borneo, Lombok in the Lesser Sunda Islands, and the Aru and Kei Islands in Maluku.[155] In the same period, the twin kingdoms became a more integral part of an international trading network of mostly Muslim states stretching from the Middle East and India to Indonesia.[156][152] The period also saw the arrivals of Chinese traders and more European nationals in Gowa's thriving port.[152][157] However, in the late 1660s, Gowa and Talloq were defeated by an alliance of the Bugis and the Dutch East India Company.[158] This ended their overlordship in South Sulawesi and replaced it with the dominance of Boné and the Dutch.[159]

Demographic and cultural shifts

The low-lying interior heartland of the kingdom around Kale Gowa had been an estuary as late as 2300 BCE. The recession of the sea as the temperature cooled meant that the former coastline became a verdant wetland, well-watered by both the Jeneberang River and the monsoon rains.[160] Such terrain is ideal for the growth of rice.[161] Large swathes of formerly unoccupied land in Gowa and its environs were settled and farmed.[162] This includes the Talloq River valley;[64] the toponym Talloq itself comes from the Makassar word taqloang meaning "wide and uninhabited", referring to the empty forests cleared during settlement.[163] Rice from South Sulawesi was commonly traded for imported goods, and its surplus supported foreign trade on an unprecedented scale.[164] A 1980s archaeological survey of Makassar and its environs found over 10,000 pre-1600 ceramic sherds from China, Vietnam, and Thailand, including a single garden field which yielded over 850 sherds.[165] According to Bulbeck and Caldwell, the scale of the ceramic importation "beggars imagination".[164] It appears that these ceramics were only a portion of the imported "exotic sumptuary goods to pre-Islamic South Sulawesi",[166] with the most common import being perishable textiles of which few examples have survived.[166] These factors contributed to sustained population growth in Gowa and its neighbors after around 1300.[39]

The general trend of rapid population increase was tempered by regional variations. For instance, the population in the countryside around Kale Gowa appears to have declined after around 1500 as the centralization of Gowa under the Karaeng Gowa's court drew rural inhabitants into the political centers of Kale Gowa and Makassar.[167] Occasional shifts in the course of the Jeneberang also affected population distribution,[168] while warfare under Tumapaqrisiq Kallonna reduced the populations of specific areas such as the upper Talloq River.[64] Nevertheless, Bulbeck variously estimates that the population of Makassar within 3.6 kilometres (2.2 mi) from the coastline had grown by three[169] to ten times between the 14th and 17th centuries.[170] The overall population of Gowa and Talloq's core territories has been estimated at over half a million,[171] although Bulbeck gives a more cautious estimate of 300,000 people within twenty kilometers of Makassar in the mid-17th century: 100,000 people in the urban center of Makassar itself, 90,000 people in the suburban districts of Talloq and Kale Gowa, and 110,000 people in outlying rural areas.[170]

The growth in foreign trade allowed for other transformations in society. In housing, new types of furniture were introduced and Portuguese words borrowed to refer to them, such as kadéra for chair from Portuguese cadeira, mejang for table from Portuguese mesa, and jandéla for window from Portuguese janela. The split bamboo floors of noble houses were increasingly replaced by wooden floors.[172][173] Western games such as ombre and dice began to spread as well. New World crops such as maize, sweet potato, and tobacco were all successfully propagated, while upper-class women abandoned toplessness.[173]

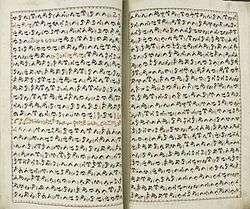

Another notable innovation in Gowa and Talloq's early history was the introduction of writing in the form of the Makassar alphabet, knowledge of which was apparently widespread by 1605.[174] However, the early history of the script remains mysterious. Although some historians have interpreted the Gowa Chronicle as stating that writing was unknown until the reign of Tumapaqrisiq Kallonna,[175][176] it is generally thought that writing existed in the region some time prior to the sixteenth century.[177][178] There is also universal agreement that the alphabet ultimately derives from an Indic source, although it remains an open question which Indic script had the greatest influence on the Makassar alphabet; the Javanese kawi script, the Batak and Rejang alphabets of Sumatra,[179][180] and even the Gujarati script of western India[181] have all been proposed.

The extent and the impact of writing are disputed. The historian Anthony Reid argues that literacy was pervasive even at a popular level, especially for women.[182] On the other hand, Stephen C. Druce contends that writing was restricted to the high elite.[183] William Cummings has asserted that writing, by being perceived as more authoritative and supernaturally potent than oral communication, wrought profound social changes among the Makassar. These included a new stress on detailed genealogies and other continuities between the past and present, a more stringently enforced social hierarchy centered on the divine descent attributed to nobility, the emergence and codification of the concept of a Makassar culture, and the "centralizing of Gowa" by which connections to Gowa became the greatest source of legitimacy for regional Makassar polities.[70] Cummings's arguments have been contested by historians such as Caldwell, who argues that authority derived from the spoken word more than the written and that histories from other Makassar areas reject a Gowa-centered view of legitimacy.[184]

Gowa's early history as state formation

Although South Sulawesi polities are generally referred to as kingdoms, archaeologists classify most of them as complex chiefdoms or proto-states rather than true state societies.[185][186][187][188] However, many archaeologists believe Gowa constitutes the first[189] and possibly only genuine state in precolonial South Sulawesi.[185][190] The case for this has been made most forcefully by Bulbeck.[185]

Bulbeck argues that Gowa is an example of a "secondary state", a state society which emerges by adopting foreign technologies and administrative institutions. For example, Gowa's military expansionism under Tunipalangga was greatly aided by the introduction of firearms and new fortification technologies.[189] The capability of Gowa's rulers to integrate foreign expertise with local society allowed sixteenth-century Gowa to satisfy eighteen of the twenty-two attributes offered by Bulbeck as the "more useful, specific criteria" for early statehood.[189] Similarly, Ian Caldwell classifies Gowa as a "modern state" marked by "the development of kingship, the codification of law, the rise of a bureaucracy, the imposition of a military draft and taxation, and the emergence of full-time craftsmen."[188]

However, the characterization of Gowa's early history as a process of state formation is not universally accepted.[191] Arguing that royal absolutism never developed in Gowa and that labor for infrastructural projects was recruited by landed nobles rather than the rudimentary bureaucracy, the historian William Cummings contends that Gowa was not a state according to Ian Caldwell's six criteria.[191] Cummings concedes that there were moves towards bureaucratization and rationalization of government, but concludes that these were of limited scope and effect—even Gowa's incipient bureaucracy was organized according to patron-client ties—and did not fundamentally change the workings of Makassar society.[191] Contemporaneous Makassars themselves did not believe that Gowa had become something fundamentally different from what had come before.[191] Ultimately, Cummings suggests that as social complexity does not evolve in a linear manner, there is little point to debating whether Gowa was a state or a chiefdom.[191]

Notes

- Also referred to as Tallo, Tallo' or Tallok according to varying transliteration schemes. The final glottal stop in South Sulawesi languages is variably written with the letter 'q', letter 'k', or an apostrophe.[1][2]

- The official Gowa and Talloq Chronicles claim that Batara Gowa was the senior brother, perhaps reflecting the senior position of Gowa for most of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, whereas a 19th-century account recording oral tradition in Talloq claims that Karaeng Loe ri Sero was the legitimate Karaeng Gowa before founding Talloq, and that Batara Gowa was the usurper.[40]

- 'Jawa' is etymologically identical to the European words for the island of Java and often translated as such, but the word is in fact a general term referring to the Central and Western Archipelago and is used most often for Malays.[42]

- However, the historian Christian Pelras believes that this account "may be not completely reliable" since this sayyid is claimed to have gone to Wajoq, in eastern South Sulawesi, even though Wajoq was of little importance in the fifteenth century.[47]

- Original (transliterated): "... taqle ri Malaka tulusuq anraiq ri Banda tallu taungi lampana nanapabattu ..."[48]

- William Cummings consistently dates Tumapaqrisiq Kalonna's reign to be from 1510 or 1511 to 1546 (Cummings 2002, 2007, 2014), as does Thomas Gibson.[56] David Bulbeck dates the reign to 1511–1547.[57] Anthony Reid suggests a reign between 1512 and 1548.[58]

- This interpretation is rooted in the statement of the Gowa Chronicle that "[Tumapaqrisiq Kalonna] was also [the first king] to have the Portuguese come ashore. In the same year he conquered Garassiq, Melaka too was conquered by the Portuguese" (original [transliterated]: "... iatonji uru nasorei Paranggi julu taungi nibetana Garassiq nibetanatodong Malaka ri Paranggia ..."[59]). Melaka was captured by the Portuguese in 1511. But this phrase may also be interpreted as suggesting that Gowa conquered Garassiq in the same year that the Portuguese arrived, and there is no evidence of Portuguese in South Sulawesi prior to the 1530s.[60][61]

- The Gowa Chronicle mentions that Tumapaqrisiq Kallonna "conquered" Sidenreng, a Bugis kingdom. However, this probably refers to Sidenre, a minor polity of Makassar ethnicity.[63]

- Polombangkeng was not ruled by a single monarch like Gowa or Talloq but rather a confederation of seven small polities, each believed to be descended from one of seven brothers.[70]

- These were Tunipalangga and Tunibatta, the next two kings of Gowa.[71] Bulbeck suggests that it was the two princes, and not Tumapaqrisiq Kallonna himself, who were responsible for the victory over Talloq.[57]

- See note [f] for the end of Tumapaqrisiq Kallonna's reign. Tunipalangga's death is generally dated to 1565,[56][80][81] but Anthony Reid dates it to 1566.[58]

- 'Captain' or 'skipper' in Malay is nakhoda, and so he is referred to as 'Anakoda Bonang' ('Captain Bonang') in Makassar chronicles and many modern secondary sources.[92]

- During the reign of Tunipalangga there was apparently only one tumailalang. Later on in the century there were effectively three, a 'senior' tumailalang with two 'junior' assistants.[99]

- Bulbeck (1992) and Gibson (2005), among others, believe that the guildmaster was a single post under Tunipalangga; Reid (2000) believes each guild had one.[102][103][104] Cummings, in his translation of the Gowa Chronicle, does not see the tumakkajananngang as a single specific post, but as a generic word for "a term or title describing those charged with supervising others who had specific tasks."[105]

- Original (transliterated): "... seqreji ata narua karaeng nibunoi tumassoqnaya angkanaya sisalai Gowa Talloq."[114]

- Tunipasuluq's claim was based upon his status as the son of Tunijalloq (of Gowa) and Karaeng Baine (of Talloq). However, while his ill-fated reign over Gowa was recognized, his attempt to rule Talloq was considered illegitimate and is only mentioned briefly in the Talloq Chronicle.[137]

References

Citations

- Cummings 2002, p. xiii

- Cummings 2007, p. 17

- Pelras 1997, p. 12.

- Abidin 1983, pp. 476–477.

- Bulbeck & Caldwell 2000, p. 106.

- Bulbeck & Caldwell 2000, p. 77

- Bougas 1998, p. 119

- Cummings 2002, p. 44

- Caldwell 1995, pp. 402–403

- Druce 2009, p. 32

- Cummings 2002, p. 100

- Caldwell 1991, pp. 113–115

- Pelras 1997, pp. 94–95

- Cummings 2007, p. vii.

- Cummings 2007, p. 18.

- Cummings 2007, p. 8.

- Hall 1965, p. 358.

- Cummings 2007, p. 3.

- Bulbeck 1992, pp. 24–25.

- Cummings 2005a, p. 40.

- Cummings 2005a, p. 41.

- Cummings 2005a, pp. 43, 53.

- Bulbeck 1992, pp. 26–27.

- Bulbeck 1992, p. 398.

- Ritcher 2000, p. 214.

- Cummings 2002, pp. 149–153

- Cummings 2002, p. 25

- Abidin 1983, pp. 474–475

- Bulbeck 1992, pp. 32–34

- Bulbeck 2006, p. 287

- Bulbeck & Clune 2003, p. 99

- Bulbeck 1992, pp. 34, 473, 475, among others

- Bulbeck 1992, p. 231

- Bulbeck 1993, p. 13.

- Bulbeck & Caldwell 2000, p. 107

- Druce 2009, pp. 34–36

- Pelras 1997, p. 232

- Pelras 1997, pp. 98–103

- Bulbeck & Caldwell 2008, p. 15

- Cummings 2002, pp. 81, 86.

- Cummings 2002, p. 81.

- Cummings 2007, pp. 2–5, 83–85

- Gibson 2005, p. 147

- Bulbeck 1992, pp. 430–432

- Reid 1983, pp. 134–135.

- Druce 2009, pp. 237–241

- Pelras 1997, pp. 135–136

- Cummings 2007, p. 97

- Reid 1983, p. 135.

- Cummings 2007, pp. 2–5, 83–85.

- Reid 1983, p. 134.

- Andaya 1981, pp. 19–20

- Villiers 1990, pp. 146–147

- Baker 2005, p. 72

- Bulbeck 1992, pp. 123–125

- Gibson 2007, p. 44

- Bulbeck 1992, pp. 117–118

- Reid 1983, p. 132.

- Cummings 2007, pp. 67–68

- Cummings 2007, p. 33

- Bulbeck 1992, pp. 121–127

- Cummings 2007, pp. 32–33

- Druce 2009, pp. 241–242

- Bulbeck 1992, pp. 348–349

- Cummings 2007, p. 57

- Bougas 1998, p. 92.

- Cummings 2014, pp. 215–218

- Cummings 2000, p. 29

- Cummings 1999, pp. 106–107

- Cummings 2002, pp. 152–153

- Cummings 2007, pp. 32–33, 36

- Bulbeck 1992, pp. 127–131

- Villiers 1990, p. 149

- Cummings 2002, p. 28

- Bulbeck 1992, pp. 105–107

- Cummings 2002, p. 216

- Cummings 2002, p. 85

- Bulbeck 1992, p. 208

- Bulbeck 1992, p. 317

- Cummings 2007, p. 4

- Bulbeck 1992, pp. 120–121, also Figure 4-4

- Cummings 2007, pp. 33–36, 56–59

- Andaya 1981, pp. 25–26

- Bulbeck 1992, p. 126

- Druce 2009, pp. 232–235, 244

- Cummings 2014, pp. 219–220

- Bulbeck 2006, p. 314.

- Druce 2009, pp. 242–243

- Gibson 2005, pp. 152–156

- Andaya 1981, p. 26

- Druce 2009, p. 242

- Sulistyo 2014, p. 54

- Sutherland 2004, p. 79

- Cummings 2007, p. 34

- Andaya 1981, p. 27

- Cummings 2014, pp. 219–221

- Bougas 1998, p. 92

- Andaya 2011, pp. 114–115

- Cummings 2002, p. 112

- Gibson 2007, p. 45

- Bulbeck 1992, p. 107

- Gibson 2005, p. 45

- Bulbeck 1992, pp. 108–109

- Reid 2000, p. 449

- Cummings 2007, pp. 34, 207

- Bulbeck 2006, p. 292

- Reid 2000, pp. 446–448

- Andaya 1981, p. 23

- Pelras 1997, pp. 131–132

- Andaya 1981, p. 29

- Cummings 2007, p. 36

- Reid 1981, p. 4.

- Bulbeck 1992, p. 102

- Cummings 2007, p. 98

- Cummings 1999, pp. 109–110

- Cummings 2007, p. 86

- Reid 1981, pp. 5–6.

- Cummings 2007, p. 38

- Druce 2014, p. 152

- Sila 2015, p. 28

- Cummings 2007, p. 41

- Cummings 2002, p. 22

- Pelras 1994, p. 139

- Pelras 1994, p. 131

- Pelras 1994, pp. 142–144

- Andaya 1981, p. 30

- Pelras 1994, p. 141

- Pelras 1994, p. 138

- Reid 2000, p. 438

- Cummings 2002, pp. 26–27

- Pelras 1997, p. 133

- Druce 2009, p. 246

- Bulbeck 1992, p. 30

- Cummings 2007, p. 87

- Cummings 2014, p. 217

- Bulbeck 1992, p. 103

- Cummings 2007, p. 94

- Cummings 2005b

- Cummings 2000, pp. 8, 19.

- Bulbeck 2006, p. 306

- Cummings 1999, pp. 110–111

- Gibson 2005, p. 154

- Reid 1981, pp. 4–5.

- Cummings 2005b, p. 46

- Cummings 2005b, p. 42

- Cummings 2007, pp. 6, 43

- Cummings 2000, p. 29.

- Bulbeck 2006, p. 288

- Reid 1981, pp. 16–17.

- Bulbeck 2006, p. 307.

- Bulbeck 1992, p. 35.

- Bulbeck & Caldwell 2000, p. 107.

- Andaya 1981, p. 32.

- Poelinggomang 1993, p. 62

- Andaya 1981, p. 33.

- Andaya 1981, p. 34.

- Andaya 1981, p. 36.

- Andaya 1981, p. 137.

- Andaya 1981, p. 142.

- Bulbeck 1992, p. 203

- Higham 1989, p. 70

- Pelras 1997, p. 99

- Cummings 1999, p. 103

- Bulbeck & Caldwell 2008, p. 16

- Bulbeck 1992, pp. 368, 608, 662–663

- Bulbeck & Caldwell 2008, p. 17

- Bulbeck 1992, p. 256

- Bulbeck 1992, p. 259

- Bulbeck 1992, pp. 461–463

- Bulbeck 1994, p. 4.

- Lieberman 2009, p. 851

- Pelras 2003, p. 266

- Pelras 1997, pp. 122–124

- Noorduyn 1961, p. 31

- Bulbeck 1992, pp. 20–21

- Reid 1983, p. 117.

- Cummings 2002, p. 42

- Jukes 2014, p. 3

- Jukes 2014, p. 2

- Noorduyn 1993, p. 567

- Miller 2010, pp. 280–283

- Reid 1988, p. 218

- Druce 2009, pp. 73–74

- Caldwell 2004, pp. 343–344.

- Druce 2009, p. 27

- Bulbeck & Caldwell 2000, p. 1

- Henley & Caldwell 2008, p. 271

- Caldwell 1995, p. 417

- Bulbeck 1992, pp. 469–472

- Caldwell 1995, p. 418

- Cummings 2014, pp. 222–224

Sources

- Abidin, Andi' Zainal (March 1983). "The Emergence of Early Kingdoms in South Sulawesi: A Preliminary Remark on Governmental Contracts from the Thirteenth to the Fifteenth Century". Southeast Asian Studies. Kyoto University Center for Southeast Asian Studies. 20 (4): 1–39. doi:10.14724/jh.v2i1.14 (inactive 2020-06-06). hdl:2433/56113. ISSN 0563-8682.

- Andaya, Leonard Y. (1981). The Heritage of Arung Palakka: A History of South Sulawesi (Celebes) in the Seventeenth Century. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan. ISBN 978-9024724635.

- Andaya, Leonard Y. (2011). "Chapter 6: Eastern Indonesia: A Study of the Intersection of Global, Regional, and Local Networks in the 'Extended' Indian Ocean". In Halikowski Smith, Stephan C. A. (ed.). Reinterpreting Indian Ocean Worlds: Essays in Honour of Kirti N. Chaudhuri. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 107–141. ISBN 978-1443830447.

- Baker, Brett (2005). "South Sulawesi in 1544: a Portuguese letter" (PDF). Review of Indonesian and Malaysian Affairs. Canberra, ACT: Association for the Publication of Indonesian and Malaysian Studies. 39 (1): 72. ISSN 0815-7251.

- Bougas, Wayne A. (1998). "Bantayan: An Early Makassarese Kingdom, 1200–1600 A.D.". Archipel. Paris. 55 (1): 83–123. doi:10.3406/arch.1998.3444. ISSN 2104-3655.

- Bulbeck, Francis David (March 1992). A Tale of Two Kingdoms: The Historical Archaeology of Gowa and Tallok, South Sulawesi, Indonesia (PhD thesis). Australian National University.

- Bulbeck, Francis David (1993). "New Perspectives on early South Sulawesi History". Baruga: Sulawesi Research Bulletin. Leiden: KITLV Press. 9: 10–18. OCLC 72765814.

- Bulbeck, Francis David (1994). Ecological Parameters of Settlement Patterns and Hierarchy in the Pre-Colonial Macassar Kingdom (PDF). Asian Studies Association of Australia Biennial Conference. Perth, WA.

- Bulbeck, Francis David; Caldwell, Ian (2000). Land of iron: the Historical Archaeology of Luwu and the Cenrana valley : Results of the Origin of Complex Society in South Sulawesi Project (OXIS). University of Hull Centre for South-East Asian Studies. ISBN 978-0903122115.

- Bulbeck, Francis David; Clune, Genevieve (2003). "Macassar Historical Decorated Earthenwares: Preliminary Chronology and Bajau Connections". Earthenware in Southeast Asia: Proceedings of the Singapore Symposium on Premodern Southeast Asian Earthenwares. Singapore Symposium on Premodern Southeast Asian Earthenwares. Singapore: NUS Press. pp. 80–103.

- Bulbeck, Francis David (2006). "Chapter 13: The Politics of Marriage and the Marriage of Polities in Gowa, South Sulawesi, During the 16th and 17th Centuries". In Fox, James J. (ed.). Origins, Ancestry and Alliance: Explorations in Austronesian Ethnography. The Australian National University Acton: ANU Press. pp. 283–319. ISBN 978-1920942878.

- Bulbeck, Francis David; Caldwell, Ian (March 1, 2008). "Oryza Sativa and the origins of Kingdoms in South Sulawesi, Indonesia: Evidence from Rice Husk Phytoliths". Indonesia and the Malay World. 36 (104): 1–20. doi:10.1080/13639810802016117. ISSN 1363-9811.

- Caldwell, Ian (March 1991). "Review: The Myth of the Exemplary Centre: Shelly Errington's "Meaning and Power in a Southeast Asian Realm"". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 22 (1): 109–118. doi:10.1017/S002246340000549X. ISSN 1474-0680. JSTOR 20071266.

- Caldwell, Ian (1995). "Power, State and Society Among the Pre-Islamic Bugis". Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde. Leiden: Brill. 151 (3): 394–421. doi:10.1163/22134379-90003038. ISSN 0006-2294. JSTOR 27864678. S2CID 59575666.

- Caldwell, Ian (2004). "Review: William Cummings, Making Blood White ; Historical transformations in early modern Makassar". Archipel. Paris. 68 (1): 343–347. ISSN 2104-3655.

- Cummings, William P. (1999). "'Only One People but Two Rulers': Hiding the Past in Seventeenth-Century Makasarese Chronicles". Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde. Leiden: Brill. 155 (1): 97–120. doi:10.1163/22134379-90003881. ISSN 0006-2294. JSTOR 27865493.

- Cummings, William P. (2000). "Reading the Histories of a Maros Chronicle". Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde. Leiden: Brill. 156 (1): 1–31. doi:10.1163/22134379-90003851. ISSN 0006-2294. JSTOR 27865583.

- Cummings, William P. (2002). Making Blood White: Historical Transformations in Early Modern Makassar. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0824825133.

- Cummings, William P. (January 2005). "Historical texts as social maps: Lontaraq bilang in early modern Makassar". Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde. Leiden: Brill. 161 (1): 40–62. ISSN 0006-2294. JSTOR 27868200.

- Cummings, William P. (2005). "'The One Who Was Cast Out': Tunipasuluq and Changing Notions of Authority in the Gowa Chronicle". Review of Indonesian and Malaysian Affairs. 39 (1): 35–59. ISSN 0815-7251.

- Cummings, William P. (2007). A Chain of Kings: The Makassarese Chronicles of Gowa and Talloq. KITLV Press. ISBN 978-9067182874.

- Cummings, Wiliam P. (October 17, 2014). "Chapter 10: Re-evaluating state, society, and the dynamics of expansion in precolonial Gowa". In Wade, Geoff (ed.). Asian Expansions: The Historical Experiences of Polity Expansion in Asia. Routledge. pp. 214–232. ISBN 978-1135043537.

- Druce, Stephen C. (2009). The Lands West of the Lakes: A History of the Ajattappareng Kingdoms of South Sulawesi, 1200 to 1600 CE. Brill. ISBN 978-9004253827.

- Druce, Stephen C. (October 2006). "Dating the tributary and domain lists of the South Sulawesi kingdoms". In Ampuan Haji Brahim bin Ampuan Haji Tengah (ed.). Cetusan minda sarjana: Sastera dan budaya. Bandar Seri Begawan, Brunei: Brunei: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka. pp. 145–156. ISBN 978-9991709604.

- Gibson, Thomas (2005). And the Sun Pursued the Moon: Symbolic Knowledge and Traditional Authority among the Makassar. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0824828653.

- Gibson, Thomas (June 11, 2007). Islamic Narrative and Authority in Southeast Asia: From the 16th to the 21st century. 11 W 42nd St, New York, NY 10036, USA: Springer Publishing. ISBN 978-0230605084.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Hall, D. G. E. (1965). "Problems of Indonesian Historiography". Pacific Affairs. Vancouver: Pacific Affairs, University of British Columbia. 38 (3/4): 353–359. doi:10.2307/2754037. ISSN 0030-851X. JSTOR www.jstor.org/stable/2754037.

- Henley, David; Caldwell, Ian (2008). "Kings and Covenants: Stranger-kings and social contract in Sulawesi". Indonesia and the Malay World. 36 (105): 269–291. doi:10.1080/13639810802268031. ISSN 1363-9811.

- Higham, Charles (1989). The Archaeology of Mainland Southeast Asia: From 10,000 B.C. to the Fall of Angkor. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521275255.

- Jukes, Anthony (2014). Writing and Reading Makassarese (PDF). International Workshop on Endangered Scripts of Island Southeast Asia. Tokyo University of Foreign Studies. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-04-28. Retrieved 2017-01-21.

- Lieberman, Victor (2009). Strange Parallels: Southeast Asia in Global Context, Volume 2, Mainland Mirrors: Europe, Japan, China, South Asia, and the Islands. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1139485173.

- Miller, Christopher (2010). A Gujarati Origin for Scripts of Sumatra, Sulawesi and the Philippines. Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society. University of California, Berkeley.

- Noorduyn, Jacobus (1961). "Some aspects of Macassar–Buginese historiography". In Hall, D. G. E. (ed.). Historians of South-East Asia. Oxford University Press. pp. 29–36.

- Noorduyn, Jacobus (1993). "Variation in the Bugis/Makassarese Script". Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde. Leiden: Brill. 149 (3): 533–570. doi:10.1163/22134379-90003120. ISSN 0006-2294. JSTOR 27864487.

- Pelras, Christian (1994). "Religion, Tradition and the Dynamics of Islamization in South-Sulawesi". Indonesia. 57 (1): 133–154. doi:10.2307/3351245. hdl:1813/54026. ISSN 0019-7289. JSTOR 3351245.

- Pelras, Christian (1997). The Bugis. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. ISBN 978-0631172314.

- Pelras, Christian (2003). "Bugis and Makassar Houses: Variation and Evolution". In Schefold, Reimar; Nas, Peter J. M.; Domenig, Gaudenz (eds.). Indonesian Houses: Tradition and transformation in vernacular architecture. KITLV Press. pp. 251–284. ISBN 978-9067182058.

- Poelinggomang, Edward L. (1993). "The Dutch Trade Policy and its Impact on Makassar's Trade". Review of Indonesian and Malaysian Affairs. 27: 61–76. ISSN 0815-7251.

- Reid, Anthony (1981). "A Great Seventeenth-Century Indonesian Family: Matoaya and Pattingalloang of Makassar". Masyarakat Indonesia. 8 (1): 1–28. ISSN 0125-9989.

- Reid, Anthony (1983). "The Rise of Makassar". Review of Indonesian and Malayan Affairs. 17 (1): 117–160. ISSN 0815-7251.

- Reid, Anthony (1988). Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce: 1450–1680. The lands below the winds. Volume 1. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300039214.

- Reid, Anthony (2000). "Pluralism and progress in seventeenth-century Makassar". Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde. Leiden: Brill. 156 (3): 433–449. doi:10.1163/22134379-90003834. ISSN 0006-2294. JSTOR 27865647.

- Ritcher, Anne (2000). Jewelry of Southeast Asia. Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 978-0-8109-3528-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sila, Muhammad Adlin (2015). Maudu': A Way of Union with God. The Australian National University Acton: ANU Press. ISBN 978-1925022711.

- Sulistyo, Bambang (2014). "Malay Emigrants and Their Islamic Mission in South Sulawesi in 16th to 17th Century". TAWARIKH: International Journal for Historical Studies. Bandung. 6 (1): 53–66. ISSN 2085-0980.

- Sutherland, Heather (2004). "The Makassar Malays: Adaptation and Identity, c. 1660–1790". In Barnard, Timothy (ed.). Contesting Malayness: Malay Identity Across Boundaries. NUS Press. pp. 76–106. ISBN 978-9971692797.

- Villiers, John (1990). "Makassar: The Rise and Fall of an East Indonesian Maritime Trading State, 1512–1669". In Kathirithamby-Wells, Jeyamalar; Villiers, John (eds.). The Southeast Asian Port and Polity: Rise and Demise. NUS Press. pp. 143–159. ISBN 978-9971691417.

External links

- The official site of the OXIS group, "an informal confederation of historians, anthropologists, archaeologists, geographers and linguists working on the origins and development of indigenous societies on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi." This site makes available a large number of articles and books on the early history of Gowa and Talloq.