Dwarf dog-faced bat

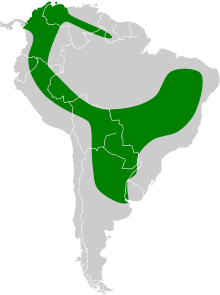

The dwarf dog-faced bat (Molossops temminckii) is a species of free-tailed bat from South America. It is found in Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Guyana, Peru, Paraguay and Uruguay, typically at lower elevations. It is one of two species in the genus Molossops, the other being the rufous dog-faced bat (M. neglectus). Three subspecies are often recognized, though mammalogist Judith Eger considers it monotypic with no subspecies. It is a small free-tailed bat, with a forearm length of 28.9–32.5 mm (1.14–1.28 in) and a weight of 5–8 g (0.18–0.28 oz); males are larger than females. It is brown, with paler belly fur and darker back fur. Its wings are unusual for a free-tailed bat, with exceptionally broad wingtips. Additionally, it has low wing loading, meaning that it has a large wing surface area relative to its body weight. Therefore, it flies more similarly to a vesper bat than to other species in its own family. As it forages at night for its insect prey, including moths, beetles, and others, it uses two kinds of frequency-modulated echolocation calls: one type is to navigate in open areas and to search for prey, while the other type is used for navigating in cluttered areas or while approaching a prey item.

| Dwarf dog-faced bat | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Chiroptera |

| Family: | Molossidae |

| Genus: | Molossops |

| Species: | M. temminckii |

| Binomial name | |

| Molossops temminckii Burmeister, 1854 | |

| |

Little is known about its reproduction, with pregnant females documented July through December in various parts of its range. Females might be capable of becoming pregnant multiple times per year, unlike some bats which have an annual breeding season. It roosts in small groups, typically three or fewer, which can be found under tree bark, in rocky outcrops or buildings, or even within holes in fence posts. Its predators may include owls, though the extent of owl depredation is unknown. It has a variety of internal and external parasites, including nematodes, cestodes, trematodes, mites, ticks, and bat flies.

Taxonomy

The dwarf dog-faced bat was first named by Danish zoologist Peter Wilhelm Lund in 1842, who placed it in the now-defunct genus Dysopes, with a scientific name of Dysopes temminckii.[2][3] However, Lund's name was deemed a nomen nudum ("naked name", or unaccepted due to inadequate taxon description), and thus Lund is not recognized as the taxonomic authority. Instead, the authority is given as German zoologist Hermann Burmeister, who was judged to have adequately described the taxon in 1854.[4][3] The holotype had been collected in Lagoa Santa, Minas Gerais, Brazil.[5] American zoologist Gerrit Smith Miller was the first to use its present name combination, placing it in the genus Molossops in 1907.[6][5] The eponym for the species name "temminckii " is Dutch zoologist Coenraad Jacob Temminck.[7]

A variable number of subspecies are recognized. Four subspecies of Molossops temminckii have been named: M. t. temminckii, M. t. griseiventer, M. t. sylvia, and M. t. mattogrossensis. The former three are still recognized as subspecies by some, though M. t. mattogrossensis is now most frequently recognized not only as a distinct species, but also in a separate genus, Neoplatymops mattogrossensis.[3] Mammalogist Judith Eger, however, did not recognize any subspecies in Mammals of South America (2008).[3][5] The dwarf dog-faced bat and the rufous dog-faced bat (M. neglectus) are the only two species in the genus Molossops. Genetic analysis suggests that the Molossops species are closely related to those in the genus Cynomops; they are in a clade along with the genera Eumops, Molossus, Promops, Nyctinomops, and Neoplatymops.[3]

Description

| Measurement | Females | Males |

|---|---|---|

| Greatest length of skull[lower-alpha 1] | 12.9 | 13.3 |

| Condylobasal length[lower-alpha 2] | 12.5 | 12.9 |

| Greatest breadth across zygoma[lower-alpha 3] | 8.6 | 9.0 |

| Least interorbital constriction[lower-alpha 4] | 3.6 | 3.7 |

| Greatest breadth across mastoid process | 8.1 | 8.5 |

| Breadth of palate and molars | 6.2 | 6.5 |

The dwarf dog-faced bat is considered small for the free-tailed bat family, Molossidae. Individuals have a total length of 60–84 mm (2.4–3.3 in), forearm length of 28.9–32.5 mm (1.14–1.28 in), and tail length of 21–34 mm (0.83–1.34 in). It weighs 5–8 g (0.18–0.28 oz). It is sexually dimorphic, with females smaller than the males; this is particularly noticeable in skull measurements. Its fur coloration is variable; back fur ranges from dark to light brown, with individuals found in forested areas darker than those in more arid ones. The belly fur is lighter in color and typically grayish. Its ears are small and triangular, with triangular tragi (cartilage projections in front of the ear canal). Its skull has a flattened top, with a weak sagittal crest. Its snout is long and flat, with a blunt tip and smooth lips. The nostrils are surrounded by wart-like bumps. Males have a gular gland used for scent marking members of a colony.[3] It has a dental formula of 1.1.1.31.1.2.3 for a total of 26 teeth.[10]

It has short thumbs with a well-developed pad at the base of each. It has distinct calcars (cartilage spurs) on the edge of its uropatagium (tail membrane); the calcars are more than half the length of the hind foot to the tail. Its wings attach to its hind limbs at the middle of the tibia. Its wings are large and broad, and it has low wing loading, meaning that it has a large wing area relative to its body weight.[3] Its wingtips are exceptionally broad for a free-tailed bat.[11] The dwarf dog-faced bat can differentiated from the rufous dog-faced bat by its smaller size; the latter typically has a forearm length greater than 36 mm (1.4 in).[12]

Biology and ecology

Reproduction

Overall, little is known about its reproduction. Pregnant females have been found in July in Venezuela, September and December in Brazil, September in Bolivia, and October and November in Argentina. Some authors have hypothesized that females may be polyestrous, or capable of becoming pregnant multiple times a year.[3] Two pregnant females found in Argentina each had a litter size of one offspring.[13]

Behavior

The dwarf dog-faced bat is moderately social, typically roosting in small groups of no more than three individuals. Groups of up to fifteen have been found roosting under the bark of Pithecellobium trees. It has flexible roosting needs, and can use rocky outcrops, buildings, tree hollows, or hollow fence posts for roosting. It is nocturnal, with individuals leaving their roosts around dusk to forage.[3]

Diet and foraging

The dwarf dog-faced bat is an insectivore, catching insects mid-flight. It is relatively slow for a free-tailed bat, which are generally adapted for high speeds, and has flight characteristics more similar to a vesper bat. Its predicted flight speed is 6.3 m/s (23 km/h; 14 mph). It uses echolocation to navigate and locate prey, utilizing two kinds of calls. The first kind of calls are upward-sloping, frequency modulated calls, starting at around 40 khz frequency and ending at 50 kHz. The calls' duration is relatively long, at an average of 7.8 miliseconds, and they are more spaced out, with 97 miliseconds between calls. These calls are used when searching for prey or navigating in uncluttered space. The second kind of calls are downward-sloping, frequency modulated calls, starting at around 65 – 70 kHz and ending at 30 – 35 KHz. These calls have a shorter duration (4.7 miliseconds) and occur closer together (interpulse interval of 50.8 miliseconds). They are used while navigating in more cluttered environments, or when approaching a prey item. Its echolocation characteristics are considered unusual for a free-tailed bat, as it uses short, frequency modulated calls at high frequencies spaced close together. These echolocation characteristics are adapted for differentiating small prey items from background clutter such as vegetation. Its diet includes beetles, moths, flies, true bugs, Hymenoptera species, and grasshoppers and katydids.[3]

Predators and parasites

Little is known about its natural predators, but its remains were once documented within the pellet of a barn owl in Argentina. Its endoparasites (internal parasites) include cestodes in the genus Vampirolepis; nematodes of the genera Allintoshius, Capillaria; and Molostrongylus, and trematodes of the genera Anenterotrema, Ochoterenatrema, and Urotrema. Its ectoparasites (external parasites) include the ticks Ornithodoros hasei and Amblyomma; the mites Chiroptonyssus venezolanus, Spinturnix americanus, Macronyssus, Trombicula, Steatonyssus, and Chiroptonyssus; the bat flies Basilia carteri (Nycteribiidae) and Trichobius jubatus (Streblidae); and true bugs of the genus Hesperoctenes.[3]

Distribution and habitat

The dwarf dog-faced bat is found only in South America, with a wide range encompassing Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Guyana, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay, and Venezuela.[1] The proposed subspecies M. t. sylvia is known from Corrientes Province, Argentina and Uruguay. Molossops temminckii griseiventer is known from Colombia in the Magdalena River Valley, as well as the Tolima, Meta, and Cundinamarca Departments. The nominate subspecies, M. t. temminckii, has been reported from Paraguay, northern Argentina, and several Brazilian states.[14] The species is generally found in lower altitude areas. The greatest elevation record for this species is 770 m (2,530 ft) above sea level, which was in Colombia. It has been found in a variety of biomes and ecoregions, including the Amazonian lowlands, Cerrado (tropical savanna), Caatinga (dry shrubland), Pantanal (wetlands), Atlantic Forest, Alto Paraná Atlantic forests, and Argentine Espinal.[3]

Notes

- measured from anterior face of incisors to posterior limit of skull

- measured from anterior surface of base of incisors to posterior surface of occipital condyles

- Greatest distance across zygomatic arches of the cranium at right angles to the long axis of skull[9]

- The least distance across the top of the skull between the eye sockets[9]

References

- Barquez, R.; Diaz, M. (2015). "Molossops temminckii". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T13643A22108409.

- Lund, P. W. (1842). "Fortsatte Bemærkninger over Brasiliens uddöde Dyrskabning" [Continued Remarks on Brazil's Extinct Animal Creation]. Det Kongelige Danske videnskabernes selskabs skrifter. 9 (in Danish): 128.

- Gamboa Alurral de, Santiago; Díaz, M Mónica (2019). "Molossops temminckii (Chiroptera: Molossidae)". Mammalian Species. 51 (976): 40–50. doi:10.1093/mspecies/sez006.

- Burmeister, Hermann (1854). "Systematische Uebersicht der Thiere Brasiliens : Welche während einer Reise durch die Provinzen von Rio de Janeiro und Minas geraës gesammlt oder beobachtet Wurden" [Systematic overview of the animals of Brazil: which were collected or observed during a trip through the provinces of Rio de Janeiro and Minas] (in German): 72–73. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.13607. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Gardner, A. L. (2008). Mammals of South America, Volume 1: Marsupials, Xenarthrans, Shrews, and Bats. 1. University of Chicago Press. pp. 417–419. ISBN 978-0226282428.

- Miller, Jr., Gerrit S. (1907). "The Families and Genera of Bats". United States National Museum Bulletin. 57: 247.

- Beolens, B.; Watkins, M.; Grayson, M. (2009). The Eponym Dictionary of Mammals. The Eponym Dictionary of Mammals. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 407. ISBN 978-0-8018-9533-3.

- Myers, P.; Wetzel, R. M. (1983). "Systematics and zoogeography of the bats of the Chaco Boreal" (PDF). Miscellaneous Publications, Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan (165).

- "Glossary". University of Texas at El Paso. 2 November 2007. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- Eisenberg, John F.; Redford, Kent H. (2000). Mammals of the Neotropics, Volume 3: Ecuador, Bolivia, Brazil. University of Chicago Press. p. 206. ISBN 978-0-226-19542-1.

- Freeman, P. W. (1981). "A multivariate study of the family Molossidae (Mammalia, Chiroptera): morphology, ecology, evolution". University of Nebraska State Museum (26): 80–81.

- Nunes, H.; Lopez, L. C.; Feijó, J. A.; Beltrão, M.; Fracasso, M. P. (2013). "First and easternmost record of Molossops temminckii (Burmeister, 1854) (Chiroptera: Molossidae) for the state of Paraíba, northeastern Brazil". Check List. 9 (2): 436–439.

- Mares, M. A.; Barquez, R. M.; Braun, J. K. (1995). "Distribution and ecology of some Argentine bats (Mammalia)" (PDF). Annals of Carnegie Museum. 64 (3): 219–237.

- Ibáñez, C.; Ochoa, J. G. (1985). "Distribución y taxonomía de Molossops temminckii (Chiroptera, Molossidae) en Venezuela" [Distribution and taxonomy of Molossops temminckii (Chiropera, Molossidae) in Venezuela] (PDF). Doñana, Acta Vertebrata (in Spanish). 12 (1): 141–150.