Duladeo Temple

The Duladeo Temple (Devanagri: दुलादेव मंदिर) is a Hindu temple in Khajuraho, Madhya Pradesh, India. The temple is dedicated to the god Shiva in the form of a linga, which is deified in the sanctum.[1][2] 'Dulodeo' means "Holy Bridegroom".[3] The temple is also known as "Kunwar Math".[1] The temple faces east and is dated to 1000–1150 AD.[1] It is the last of the temples built during the Chandela period. The temple is laid in the seven chariot plan (saptarata).[4] The figurines carved in the temple have soft expressive features unlike other temples. The walls have a display of carved celestial dancers (apsara) in erotic postures and other figures.[5][6]

| Duladeo Temple Khajuraho | |

|---|---|

दुलादेव मंदिर | |

Duladeo Temple at Khajuraho | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Hinduism |

| District | Chattarpur, Khajuraho[1] |

| Deity | Shiva[1] |

| Location | |

| Location | Khajuraho[1] |

| State | Madhya Pradesh |

| Country | India |

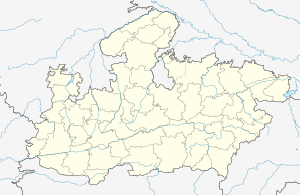

Location in Madhya Pradesh | |

| Geographic coordinates | 24°51′11″N 79°55′10″E |

| Architecture | |

| Creator | Chandella Rulers |

| Completed | Circa A.D. 1000–1150.[1] |

| Temple(s) | 1 |

Location

The temple is located on the bank of the Khodar River in the southern group of the Khajuraho Group of temples in Khajuraho village in an area spread over 6 square kilometres (2.3 sq mi). It is 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) away from the Khajuraho village close to the Jain enclosure.[7][1] The approach road is rough.[8]

History

Duladeo Temple is one of the 22 temples to the Hindu god Shiva, which are among the 87 temples that were created by the Chandela rulers of Central India. The peak period of building activity was from 950-1050 AD in the small village of Khajuraho.[9] The temples belong to the traditional religions of Hinduism and Jainism. They are identified under three groups or three zones - the western zone, the eastern zone and the southern zone. Ibn Batuta, the Moroccan traveller had attested to the existence of these temples even in 1335. The temples in the southern group are the Duladeo and Chaturbhujs. All the extant temples were inscribed in 1986 under the UNESCO List of World Heritage Sites under Criterion III for its artistic creation and under Criterion V for the culture of the Chandellas that was popular till the country was invaded by Muslims in 1202.[10] It is also said that Madanaverman (1128–1165) of the Chandela dynasty built this temple during his reign.[11]

The sculptures in the temple have strong identity with those found among the remnants of a temple in Jamsor near Kanpur in Uttar Pradesh. From this similarity it has been inferred that the sculpturing at both locations were the handiwork of the same sculptors and further that they were created during the period from 1060-1100, during the reign of Kirttivarman.[12] However, Archaeological Survey of India has inferred the period of temple building activity in Khajuraho from 950 to 1150 AD based on palaeography and the architectural style.[1]

From the name Vasala inscribed at a number of locations in the temple, it is inferred that the name is of the chief sculptor who created the sculptures.[13]

Architecture

The temple is categorized as a nirandhara temple. Nirandhara means a layout without the ambulatory path[14] consisting of a sanctum without an ambulatory, a vestibule, main hall (maha-mandapa), and an entrance porch.[1] The layout of the temple does not have a circumambulatory passage which is probably due to the fact that it was the last of the temples built in the 12th century during the reign of Chandelas, when the peak period of their construction phase had already passed.[15] The temple pinnacle (shikhara) is created in three rows of minor shikharas.[1] Its features are in general conformity with those adopted for the other temples in the Khajuraho complex. The classification according to the physical characteristics of the monuments consists of a raised base, which is a sub structure over which the richly decorated structure rises and is covered with rich sculptures.[16] The architectural style is Nagara, representing Mount Kailash, the abode of Shiva.[16]

The main hall in the temple is very large and octagonal in shape. Its ceiling has elegantly carved celestial dancers (apsaras). There are twenty such brackets carved with the apsaras, with two or three apsaras next to each other in each bracket, and arranged in the ceiling in a corbelled circle.[1] The damsels dancing around trees, and women in erotic poses are also part of the temple architecture. It is said to be the "last glow of Khajuraho's architectural and sculptural mastery".[7] The top rows in the facade have sculptures of supernatural beings (vidyadhara) in a vibrant mode. In the porch entrance, there are sculptures of river-goddesses under cover of umbrellas and decorations of pompons.[1]

A striking sculpture is of a profile carving of a celestial dancer in the inner passage of the temple hemmed between buttresses, which has decoration of a necklace with hands poised as if to throw a dice.[17] Another similarity noted between the ruins of Jamsor temple and Duladeo is the canopy of sculptures of mango trees and fruits, which are symbols of fertility. The figurines set with in these trees project out and have well finished front face but exhibit "double chin and sharply arched eyebrows". These are all richly decorated with ornaments.[12] Also notable are a carving of a flying god (deva), which is decorated with a long rectangular shaped necklace. There is also a carving of the trinity of Surya, Brahma and Shiva.[18]

A figure of Shiva is carved on the lintel at the entrance to the sanctum (garbhagriha). The central icon of the linga in the sanctum is not the original but a duplicate, as the original is untraced.[19] Worship is offered at the temple by the local people. A unique feature of the depictions on the linga is that it has 999 more lingas carved all around its surface. Its religious significance is that going round the linga would amount to taking of circumambulation a 1,000 times around it.[20]

The architecture copies the old style as it was built at the end of the Chandela period, and hence the sculptures are stated to be "wooden" and "stereotyped" compared with other earlier temples in the complex.[8] However, the elegance and grace of the figurines of women are more like "pin-ups" and there are also few figurines in the erotic poses of couples engrossed in love (mithuna).[8]

By the time the British arrived, the temple was in a state of disrepair and partly ruined. The shikara was restored as were the side walls and columns. The restored parts are discernible in the lighter colour of the sandstone, and that they are not carved and devoid of any sculptures or decoration.

Gallery

- Closer view of the restored pinnacle and walls

- Various sculptures depicting Nandi and Shiva

- Various sculptures depicting Shiva and Parvati

See also

References

- Notes

- "Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) – DulaDeo Temple". Archaeological Survey of India (ASI). Retrieved 21 March 2012.

- Pacaurī 1989, p. 35.

- Kramrisch 1976, p. 365.

- Shah 1988, p. 56.

- Pacaurī 1989, p. 32.

- Gajrani 2004, p. 88.

- Kumar 2003, p. 114.

- Sajnani 2001, p. 201.

- "Khajuraho". Official website of Madhya Pradesh Tourism. Archived from the original on 21 October 2013. Retrieved 5 October 2013.

- "Evaluation Report:World Heritage List No 240" (PDF). UNESCO Organization. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- Sullere 2004, p. 26.

- Indian Sculpture: 700-1800. University of California Press. 1988. p. 115–. ISBN 978-0-520-06477-5.

- Kramrisch 1976, p. 377.

- "The Religious Imagery of Kajuraho" (pdf). Columbia Education. p. 178. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- Kuiper 2010, p. 309.

- "World Heritage Centre (UNESCO) – 240 – Khajuraho Group of Monuments". UNESCO Organization. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- Kramrisch 1976, p. 381.

- Gangoly 1957, p. 23.

- Mitra 1977, p. 198.

- Knapp 2009, p. 109.

- Bibliography

- Gangoly, Ordhendra Coomar (1957). The Art of the Chandelas. snippets. Rupa.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gajrani, S. (2004). History, Religion and Culture of India. Isha Books. ISBN 978-81-8205-064-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Knapp, Stephen (1 January 2009). Spiritual India Handbook. Jaico Publishing House. ISBN 978-81-8495-024-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kuiper, Kathleen (15 August 2010). The Culture of India. The Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-61530-149-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kumar, Brajesh (2003). Pilgrimage Centres of India. Diamond Pocket Books (P) Ltd. ISBN 978-81-7182-185-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kramrisch, Stella (1976). The Hindu Temple. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0224-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mitra, Sisirkumar (1 January 1977). The Early Rulers of Khajurāho. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1997-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pacaurī, Lakshmīnārāyaṇa (1989). The Erotic Sculpture of Khajuraho. snippets. Naya Prokash. ISBN 978-81-85109-79-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sajnani, Manohar (2001). Encyclopaedia of Tourism Resources in India. Kalpaz Publications. ISBN 978-81-7835-017-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shah, Kirit K. (1 January 1988). Ancient Bundelkhand: Religious History in Socio-economic Perspective. Gian Books. ISBN 978-81-212-0189-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sullere, Suśīla Kumāra (1 January 2004). Chandella Art. Aakar Books. ISBN 978-81-87879-32-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

![]()