Dudley Castle

Dudley Castle is a ruined fortification in the town of Dudley, West Midlands, England. Originally a wooden motte and bailey castle built soon after the Norman Conquest, it was rebuilt as a stone fortification during the twelfth century but subsequently demolished on the orders of King Henry II. Rebuilding of the castle took place from the second half of the thirteenth century and culminated in the construction of a range of buildings within the fortifications by John Dudley. The fortifications were slighted by order of Parliament during the English Civil War and the residential buildings destroyed by fire in 1750. In the nineteenth and early twentieth century the site was used for fêtes and pageants. Today Dudley Zoo is located in its grounds.

| Dudley Castle | |

|---|---|

| Part of Dudley Zoological Gardens | |

| Dudley, West Midlands | |

The keep of Dudley Castle | |

Dudley Castle | |

| Coordinates | 52.5142°N 2.0800°W |

| Type | Motte and Bailey |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Dudley Metropolitan Borough Council |

| Controlled by | Dudley and West Midlands Zoological Society |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Condition | Ruined |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1070 |

| Built by | Ansculf de Picquigny |

| In use | Until 1750 |

| Materials | Limestone |

| Battles/wars | The Anarchy English Civil War |

Its location, Castle Hill, is an outcrop of Wenlock Group limestone that was extensively quarried during the Industrial Revolution and which now, along with Wren's Nest Hill, is a scheduled monument of the best surviving remains of the limestone industry in Dudley. It is also a Grade I listed building. The Dudley Tunnel runs beneath Castle Hill, but not the castle itself.

History

Medieval

The antiquarian William Camden claimed a castle was constructed at Dudley about the year 700 by a Mercian duke named Dodo or Doddo [1] and some subsequent histories and articles repeated this claim.[2] However, this assertion is not taken seriously by today's historians, who usually date the castle from soon after the Norman Conquest of 1066.[1] It is thought one of the Conqueror's followers, Ansculf de Picquigny, built the first castle in 1070.[3] The Domesday Book records that Ansculf's son, William Fitz-Ansculf, was in possession of the castle when it was recorded at the time of the survey of 1086. The first line of the Domesday entry for Dudley translates as: "the said William held Dudley; and there is his castle".[4] Some of the earthworks from this castle, notably the "motte", the vast mound on which the present castle keep now sits, still remain. However the earliest castle would have been of wooden construction and no longer exists.[5]

After Fitz-Ansculf, the castle came into the possession of the Paganel family, who built the first stone castle on the site. This castle was strong enough to withstand a siege in 1138 by the forces of King Stephen.[6] However, after Gervase Paganel joined a failed rebellion against King Henry II in 1173 the castle was demolished by order of the king. The Somery's were the next dynasty to own the site when Ralph de Somery I succeeded his uncle, Gervase Paganel in 1194. Roger de Somery II set about rebuilding the castle in 1262. The castle was far from complete on the death of Roger de Somery II in 1272 and construction carried on from this time into the 14th century by Roger's heirs.[7] The keep (the most obvious part of the castle when viewed from the town) and the main gate date from this re-building.

.jpg)

The last of the male line of Somery, John Somery, died in 1321. It is thought that the fortifications were complete by this date.[1] The castle and estates passed to John Somery's sister Margaret and her husband John de Sutton. Subsequently, members of this family often used Dudley as a surname. John and Margaret were only in possession of the castle for a few years before the property was seized by the younger Hugh Despenser, a favourite of King Edward II.[8] Despenser owned the castle from 1325-1326, being dispossessed when the king fell from power. The castle was returned to John and Margaret in 1327.[8] It was probably during the time of John and Margaret's son and successor John Sutton II that a chapel and great chamber were added within the castle walls.[1] Following the death of John Sutton II, the castle passed to his wife, Isabel, daughter of John de Cherleton who held it until her death in 1397.

Early modern

In 1532 another John Sutton (the seventh in the Dynasty named John) inherited the castle but after having money problems was ousted by a relative, John Dudley, later Duke of Northumberland, in 1537. John Dudley was the great-grandson of John Sutton, 1st Baron Dudley and had risen to prominence during the reign of King Henry VIII. Starting around 1540, a range of new buildings were erected within the older castle walls by him. The architect was William Sharington and the buildings are thus usually referred to as Sharington Range. According to Historic England, the Sharrington Range represents "one of the earliest known examples of the influence of the Italian Renaissance on the secular architecture of the West Midlands." [9] John Dudley was executed in 1553 for his attempt to set Lady Jane Grey on the throne of England.[5]

.jpg)

The castle was returned to the Sutton family by Queen Mary, ownership being given to Edward Sutton. The castle was visited by Queen Elizabeth I in August 1575[10] and was considered as a possible place of imprisonment for Mary, Queen of Scots. However, the Sutton family were not destined to hold the castle for much longer and Edward Sutton's son, Edward Sutton III was the last of the male line to possess the property. In 1592, this Edward sent men to raid the property of Gilbert Lyttelton, carrying away cattle which were impounded in the Castle grounds.[1] Financial difficulties continued to mount, however, until Edward Sutton III solved the problem by marrying his granddaughter and heir, Frances Sutton, to Humble Ward, the son of a wealthy merchant.

Civil War

During the First English Civil War the castle was held by a Royalist garrison commanded by Colonel Thomas Leveson, a local Catholic who was later one of only 25 former Royalists listed by Parliament in 1651 as subject to 'perpetual banishment and confiscation.'.[11] It was besieged by Parliamentary forces in 1644 and finally surrendered to forces led by Sir William Brereton on 13 May 1646.[12] The castle was partly demolished to prevent it being used again and the present ruined appearance of the keep results from this decision. However some habitable buildings remained and were subsequently used occasionally by the Earls of Dudley although by this time they preferred to reside at Himley Hall, approximately four miles away, when in the Midlands.[5]

Final years and ruin

.jpg)

A stable block was constructed on the site at some point before 1700. This was the final building to be constructed in the castle.[5]

The bulk of the remaining habitable parts of the castle was destroyed by fire in 1750. However, in the nineteenth century, the site found a new use as a 'Romantic Ruin' and a certain amount of tidying up of the site was carried out by the Earls of Dudley. Battlements on one of the remaining towers were reconstructed and two cannon captured during the Crimean Wars were installed. In the nineteenth and early twentieth century the site was used for fêtes and pageants. In 1937, when the Dudley Zoo was established, the castle grounds were incorporated into the zoo.

Location

The castle is located on a hill at one end of Dudley Town centre with the entrance (shared with Dudley Zoo) to the grounds off Castle Hill (the A459). The hill is an outcrop of limestone that was extensively quarried during the Industrial Revolution.[14]

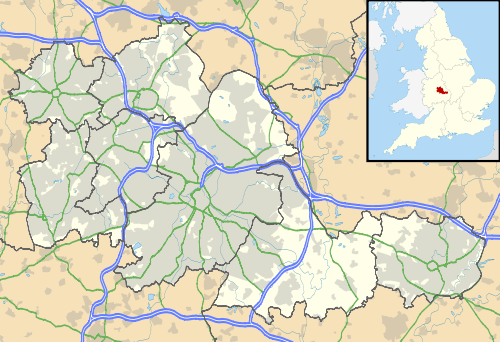

Despite being situated on the edge of Dudley town centre, historically the castle was situated within the borders of Sedgley – which was part of neighbouring Staffordshire rather than Worcestershire as shown by the maps of Christopher Saxton drawn in 1579 and John Speed in 1610.[15] The borders were changed to include the castle and its grounds within the Dudley borough only in 1926, when restructuring of the boundaries took place to allow the development of the Priory Estate.[16]

The castle remains

Motte and bailey

The motte is the oldest remaining structure at the castle site. It originally had a moat at its foot which could have been wet or dry. The motte has a core of limestone rubble encased in clay.[17] It stands around 9 metres high.[9] The oval-shaped bailey, which measures 100 metres north to south and 80 metres east to west is surrounded by a dry moat. In the medieval period, there were probably buildings in an outer court beyond the bailey moat.[9]

The keep

The castle keep dates from the rebuilding that started in 1262. It rests on the motte, constructed in the Norman period but somewhat reduced in height afterwards.[18] The original building was slightly rectangular in plan with approximate dimensions 15 metres north to south and 22 metres east to west. The four drum towers on each corner are 9.8 metres in diameter.[9] After the slighting at the end of the civil war, only the north side of the castle and parts of two of the drum towers remain.

Main gatehouse

A little to the east of the keep is the main gatehouse. Like the keep, it was subject to slighting at the end of the Civil War. Some elements of the Paganell's Norman castle remain in the structure but it mainly dates from the rebuilding carried out after 1262 by the de Somery family. A double gateway with two portcullises was constructed at this time. Under the Suttons, a barbican was added to the outside of the gatehouse so that the whole structure is sometimes called the 'Triple Gate'.[18] Originally the gatehouse was connected to the keep by a thick curtain wall. When built, the gatehouse had three floors with the machinery for operating the portcullises on the first floor and a guard room on the second floor. Above the guard room were the battlements.

Great chamber and chapel block

Probably constructed during the time of John Sutton II but re-modelled in the Tudor era when the Sharington Range was built for John Dudley. The block was in ruins before the fire of 1750.[18]

Sharington range

Constructed for John Dudley, starting around 1540, the three-storey range included a great hall, kitchen, servery, buttery, cellars and bedrooms. A small amount of masonry dating from the early Paganell castle is evident in the ruins. The range was destroyed by the fire of 1750.

Stable block

Once thought to be lodgings, the stable block was one of the last buildings constructed at the castle site, dating from before 1700. The block is situated between the Main Gate and the base of the motte.

Elizabethan gatehouse and east watch tower

In front of the main gate but further down the hill is a gatehouse dating from the Elizabethan era. A wall runs to the east of this gate to a round tower, built at the same time, known as the watch tower.

Cannon

Two Russian cannon brought back as trophies from the Crimean War are installed in prominent positions on the remains of the two south-facing drum towers. The cannon were brought to the castle in June 1857 during one of the Dudley Castle Fêtes.[19]

Visitor centre

The castle visitor centre was opened by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II in June 1994, and amongst other exhibits housed a computer generated reconstruction of the castle as it was in 1550, displayed through hardware that demonstrated the first use of the virtual tour concept, prior to its widespread adoption as a Web-based browser utility. More details of how Her Majesty became the first Royal to experience a virtual world here.

List of lords of Dudley Castle

Dudley Castle was the capital of the feudal barony of Dudley.

- Ansculf de Picquigny, a Norman who took part on the Battle of Hastings

- William Fitz-Ansculf, his son

- Fulke Paganell (fl.1100-30)

- Ralph Paganell (fl.1130s-1150s), his son

- Gervase Paganell (d.1194), his son

- Ralph de Somery I (d.1210), son of John de Somery and Hawyse sister and heir of Gervase Paganell

- Ralph de Somery II (c.1193-1216), eldest son of Ralph I

- William Percival de Somery (d.1222), his brother

- Nicholas de Somery (d.1229), still a minor

- Roger de Somery I (d.1225), 3rd son of Ralph I

- Roger de Somery II (d.1272), his son

- Roger de Somery III (c.1254-1291), his son

- Agnes de Somery (d.1309), his widow and guardian of her son

- John de Somery (1280-1322), their son

On his death the lands of the barony were divided between his two sisters. Weoley Castle went to Joan de Botetourt and her husband John de Botetourt. Dudley Castle passed to her elder sister Margaret, who had married John de Sutton I. John de Sutton II was summoned to Parliament, but none of his successors were until John de Sutton VI

- John de Sutton I (d.1327) in the right of Margaret

- John de Sutton II (d.1360), their son

- Isabel Cherleton de Sutton (d.1397), his widow held Dudley jointly with her son

- John de Sutton III (d.1369), her son - outlived by his mother

- John de Sutton IV (1360-1391), his son - outlived by his grandmother

- John de Sutton V (1380-1406), his son

- Constance de Sutton (d.1422), his widow

- John Sutton, 1st Baron Dudley 1400-87, their son

For the evolution of the castle and estate until 1740 see Baron Dudley and from the late 17th century until the 20th century as Baron Ward John de Sutton I

References

- Chandler, G.; Hannah, I.C. (1949). Dudley: As it was and as it is to-day. London: B.T.Batsford Ltd.

- "DUDLEY CASTLE AND THE DUDLEYS". The Spectator. Retrieved 2015-02-11.

- "The fates and fortunes of Dudley Castle". Dudley Zoo. Archived from the original on 2010-06-12. Retrieved 2012-04-01.

- Booker, Luke (1825). A descriptive and historical account of Dudley castle, and its surrounding scenery. London: Nicols. p. 62.

- "Dudley Castle - A Brief History". Dudley Mall. 2011. Retrieved 2012-04-01.

- John Hemingway. "A Brief History of Dudley Town and Castle". Dudley Metropolitan Borough Council. Archived from the original on 2010-12-23. Retrieved 2012-04-01.

- Hemingway, John (2006). An Illustrated Chronicle of the Castle and Barony of Dudley 1070-1757. Dudley: The Friends of Dudley Castle. pp. 35–46. ISBN 9780955343803.

- Hemingway, John (2006). An Illustrated Chronicle of the Castle and Barony of Dudley 1070-1757. Dudley: The Friends of Dudley Castle. p. 53. ISBN 9780955343803.

- Historic England. "Dudley Castle (1014042)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2017-02-06.

- Hemingway, John (2006). An Illustrated Chronicle of the Castle and Barony of Dudley 1070-1757. Dudley: The Friends of Dudley Castle. p. 86. ISBN 9780955343803.

- Smith, G (2003). The Cavaliers in Exile 1640-1660 (2014 ed.). Palgrave Macmillan. p. 55. ISBN 1349510718.

- Heath, James (1676). A chronicle of the late intestine war in the three kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland. London: J.C. for Thomas Basset. p. 106. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- Mackenzie, J. D. (1897). The Castles of England: their story and structure. Macmillan. p. 458.

- Historic England. "Lime working remains in Dudley (1021381)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2017-02-06.

- Richardson, Eric (2000). The Black Country as Seen through Antique Maps. The Black Country Society. ISBN 0-904015-60-2.

- "A Brief History of Sedgley". Sedgley Manor Productions. Retrieved 2012-04-01.

- Hemmingway, John; Tyson, Joan (3 March 2016). "The Archaeology of Dudley Castle". www.dudleycastle.org.uk. Archived from the original on 5 January 2017. Retrieved 2017-04-05.

- Hemingway, John (2006). An Illustrated Chronicle of the Castle and Barony of Dudley 1070-1757. Dudley: The Friends of Dudley Castle. pp. 120–149. ISBN 9780955343803.

- Clarke, C.F.G. (1881). The Curiosities of Dudley and the Black Country. Birmingham: Buckler Brothers. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dudley Castle. |

.jpg)