Dronninggård

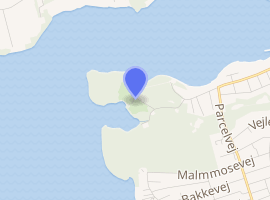

Næsseslottet is an 18th-century country house located on the shores of lake Furesøen at Holte north of Copenhagen, Denmark. The name, which translates as "Peninsula House", is a reference to the buildings setting on a narrow peninsula which extends from the east shore of the lake. The estate had previously been a royal farm known as Dronningegård and this name has long been associated with the locale.

| Dronninggård | |

|---|---|

Næsseslottet manor seen from the south | |

| |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Neoclassical |

| Location | Rudersdal, Copenhagen, Denmark |

| Country | Denmark |

| Coordinates | 55.8065671153°N 12.4343867952°E |

| Completed | 1783 |

| Client | Frédéric de Coninck |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | Andreas Kirkerup |

History

Queen Sophie Amalie

Dronninggård was built in 1661 to manage the Crown's extensive holdings of farm land in the area. The farm belonged to Queen Sophie Amalie until her death in 1714. After that, the property was sold and changed hands several times but eventually it fell into a state of despair.[1]

Frédéric de Coninck

The main building stood as a ruin when the estate was acquired by Frédéric de Coninck (1740–1811). Originally from the Netherlands, he had emigrated to Denmark in 1763 where he had set up a shipping company and made a fortune in foreign trade. He commissioned court architect Andreas Kirkerup to build a new house while the old building was rebuilt and converted into a farm. [2]

.jpg)

When Frédéric de Coninck acquired the Moltke's Mansion (now known as Danneskiold-Laurvig Mansion) in Copenhagen in 1783, to serve as his new residence during the winter season, he commissioned the painter Erik Pauelsen (1749–1790) to create two large paintings and three overdoors with motifs of his Dronninggård estate.[3] [4]

In 1804 Frédéric de Coninck built Frederikslund as a country home for his son Louis Charles Frédéric de Coninck (1779-1852).The building is located half a kilometer east of Dronninggaard and offered a view over Furesøen. It was designed by the French architect Joseph-Jacques Ramée (1764–1842). [5]

Later history

_(2).jpg)

After de Coninck's death at Næsseslottet in 1811, both the shipping empire and the Dronninggård estate was passed on to his son but the times were changing. Denmark was experiencing hard times after the state bankruptcy in 1813 and after de Coninck's company went bankrupt in 1821, Dronninggård had to be sold. The following owners generally preferred to reside at Frederikslund while Næsseslottet fell into neglect.[6]

In 1898, it was acquired by a consortium and turned into a hotel while most of the land was sold off in lots. However, the venue was no great success and in 1906 the property was sold to book publisher August Bagge. Later in the century the estate was acquired by Copenhagen Municipality and turned into a medical facility. In 1984 the Danish Red Cross used the building as their first refugee centre in Denmark. In 1986 it once again passed into private ownership and has now been turned into an office hotel.[7]

Architecture

Built in Neoclassical architecture style of Andreas Kirkerup (1749–1810), the main house consists of three storeys under a hipped roof with black-glazed tiles. The main facade is seven bays long. Of the original 18th century interiors, only the dining room has been preserved. [8]

Park and monuments

Frédéric de Coninck charged the Flemish landscape architect Jean Frédéric Henry de Drevon (1734-1797 with the design of the surrounding parklands. Drevon was inspired by the manor house gardens of southern England and created the first Romantic garden in Denmark.[9] It was planted with exotic trees many of which still grow there today. The pavilions in the park are not from the original English garden. [10]

The park is also home to a number of monuments and decorative features. The sculptor Carl Frederik Stanley (c. 1738–1813) created several monument for the park, including one to trade and shipping. Johannes Wiedewelt (1731–1802) contributed with an obelisk and ornamental vases. [11] [12]

The two pavilions and the stables were designed by Axel Berg (1856–1929) and are from about 1900.[13] [14]

List of owners

- (1660-1685) Queen Sophie Amalie

- (1685-1762) The Crown

- (1772-1776) W. D. W. Staffeldt

- (1776-1781) Ole Svendsen

- (1781-1822) Frédéric de Coninck

- (1822-1845) J. M. Jenisch

- (1845-1851) Th. R. Fønss

- (1851-1860) Hans Hansen

- (1860-1866) Johannes Christopher Nyholm

- (1866- ) Andreas Westenholz

- ( -1895) Enke efter Andreas Westenholz

- (1895-1902) Aktieselskab

- (1902-1906) A/S Næsset

- (1906-1935) F. A. Bagge

- (1935-1985) Københavns Kommune

- (1985- ) Michael Tesone

- ( -1998) Peter Kjær

- (1998- ) Næsseslottet Aps

See also

References

- "Tidslinie" (in Danish). Næsslottet. Archived from the original on 2012-03-10. Retrieved 2012-05-28.

- "de Coninck, Frédéric, 1740-1811". Dansk biografisk Lexikon. Retrieved August 1, 2020.

- "The Dronninggård Chamber". Moltkes Palæ. Archived from the original on 2012-08-02. Retrieved 2012-05-29.

- "Erik Pauelsen". Den Store Danske. Retrieved August 1, 2020.

- "Frederikslund, Holte". Trap Danmark. Retrieved August 1, 2020.

- "Looking for a different adventure?" (in Danish). geocaching. Retrieved 2012-05-30.

- "Historie" (in Danish). Næsseslottet. Archived from the original on 2012-02-04. Retrieved 2012-05-30.

- "Kirkerup, Andreas Johannes". Dansk biografisk Lexikon. Retrieved August 1, 2020.

- "Næsseslottet" (in Danish). Rudersdal Kommune. Archived from the original on 2013-04-20. Retrieved 2012-05-29.

- "Jean Frédéric Henry de Drevon". Kulturcentret Assistens. Retrieved August 1, 2020.

- "Carl Frederik Stanley". Dansk Biografisk Leksikon. Retrieved August 1, 2020.

- "Johannes Wiedewelt". britishart.yale.edu. Retrieved August 1, 2020.

- "Sag: Næsseslottet, Dronninggård". Kulturstyrelsen. Retrieved 2012-05-29.

- "Axel Berg". Den Store Danske. Retrieved August 1, 2020.