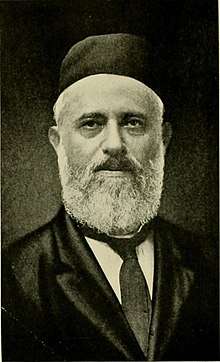

Dov Behr Manischewitz

Dov Behr Manischewitz (1856 or 1857[1] or 1858[2] in Salant – March 8, 1914, in Cincinnati, Ohio)[2], also known as Dov Ber,[3] Dov Baer,[4][5] Dov Bear,[6][7] Dave Behr,[2] and David Behr,[8] and born Dov Behr Abramson,[9][10] was a Lithuanian-American rabbi and businessman, known for his innovations in the manufacture of matzah, and for his creation of the company bearing his name.

Early life

Manischewitz was born and raised in Salant,[11] and studied under Rabbi Israel Salanter in Memel,[12] where he trained as a shochet.[2] In 1885, he emigrated to the United States,[2][13] using the identification documents of a dead man named "Manischewitz".[13][9][10][14] Although he stated that he emigrated because he had been hired as a shochet by the Jewish community of Cincinnati,[2] other reasons have been suggested, including that it was in response to the then-imminent expulsion of Jews from Memel,[3] or that it was in order to avoid compulsory military service.[10][9]

Professional life

In Cincinnati, Manischewitz initially worked as a shochet and peddler;[9] since matzah was not available, he made his own in his basement – originally for his circle of acquaintances, but later for Jews throughout the city.[9] Eventually his merchandise was successful enough that he undertook mass production, and shifted to new, mechanized methods,[13] including gas stoves[15] and the conveyor belt-based "traveling carrier bake-oven", which he patented.[16] These methods were initially controversial, and questions were raised as to whether machine-made food complied with kashrut;[3][12] however, Manischewitz argued his case with American rabbinical authorities, who decided in his favor (historian Zalman Alpert has noted that both Manischewitz and the American rabbinical authorities were of the Lithuanian Jewish tradition).[17]

His matzah business was successful enough that in 1913, he was able to move to the upscale Cincinnati neighborhood of Walnut Hills.[18] As well, he sponsored the creation of the Manischewitz yeshiva in what was then Palestine; decades later, his sons argued in court that their continued funding of the yeshiva was a business expense, as its graduates would help to spread the idea that machine-made matzah could still be kosher.[5]

Manischewitz died in 1914, and is buried in Beth Hamedrash Hagodol cemetery, Covedale.[19]

References

- Manischewitz: The Matzo Family : the Making of an American Jewish Icon, by Laura Manischewitz Alpern; published 2008 by KTAV Publishing House; p. 137, "he died in March 1914, at age fifty-seven"

- Prominent Jews of America; a collection of biographical sketches of Jews who have distinguished themselves in commercial, professional and religious endeavor, published 1918 by the American Hebrew Publishing Company; p 191, "the Late Rabbi Dave Behr Manischewitz"

- How Matzah Became Square: Manischewitz and the Development of Machine-Made Matzah in the United States, by Jonathan D. Sarna – Sixth Annual Lecture of the Victor J. Selmanowitz Chair of Jewish History, Touro College; archived at Brandeis University; first published 2005. Retrieved May 11, 2019

- United States Jewry, 1776–1985: Volume 4, The East European Period, The Emergence of the American Jew Epilogue, by Jacob Rader Marcus, first published 1993 by Wayne State University Press, "Baer Manischewitz, of Cincinnati, known for his matzos"

- B. MANISCHEWITZ CO. v. COMMISSIONER – Docket No. 13236 – 10 T.C. 1139 (1948), archived at Leagle.com

- Why Food Scares Just Aren't Kosher, by Lianne George, in Maclean's ; published December 8, 2008. Retrieved May 11, 2019

- MANISCHEWITZ, E. JUDY, in The New York Times; published December 8, 2008. Retrieved May 11, 2019

- The Concise Dictionary of American Jewish Biography: M, edited by Jacob Rader Marcus and Judith M. Daniels (Brooklyn, NY: Carlson Publishing, Inc., 1994)

- How Manischewitz Matzo Helped Make America, by Gil Marks, in The Forward; published April 18, 2011. Retrieved May 11, 2019

- Man, oh man: How Manischewitz created a matzah empire, in J. The Jewish News of Northern California; published March 26, 2010. Retrieved May 11, 2019

- Manischewitz: The Matzo Family : the Making of an American Jewish Icon, by Laura Manischewitz Alpern; published 2008 by KTAV Publishing House; p. 16, "his childhood in Salant"

- A Father of Industrial Gefilte Fish Dies, by David B. Green, in Haaretz; published September 20, 2013. Retrieved May 11, 2019

- Our Food Roots: How Cincinnati Jews changed how America ate, by Polly Campbell, in the Cincinnati Enquirer, published December 6, 2018. Retrieved May 11, 2019

- Days of Wine and Matzos: How a Cincinnati family became the name in kosher foods, by Paul Lukas, at CNN; published April 1, 2004. Retrieved May 11, 2019

- The B. Manischewitz Company, LLC. in International Directory of Company Histories (at Encyclopedia.com); published 2006 by Thomson Gale)

- The Americanization of Matzah, at The Jacob Rader Marcus Center of the American Jewish Archives. Retrieved May 11, 2019

- "Manischewitz Family", by Zalman Alpert, in the Encyclopedia of Jewish American Popular Culture; edited by Jack R. Fischel; published 2008 by ABC-CLIO

- Not By Bread Alone, by Grace Dobush, in Cincinnati; published April 14, 2014. Retrieved May 11, 2019

- CORNER STONES, by Amy Knueven Brownlee, in Cincinnati; published November 12, 2014. Retrieved May 11, 2019