Don Sharp

Donald Herman Sharp (19 April 1921 – 14 December 2011) was an Australian-born British film director.

Don Sharp | |

|---|---|

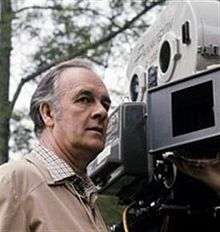

Filming The Four Feathers (1978) | |

| Born | Donald Herman Sharp 19 April 1921 |

| Died | 14 December 2011 (aged 90) Wadebridge, Cornwall, England |

| Nationality | Australian |

| Occupation | Producer, director, writer, actor |

| Known for | The Kiss of the Vampire (1962), Rasputin, the Mad Monk (1966) |

His best known films were made for Hammer in the 1960s, and included The Kiss of the Vampire (1962) and Rasputin, the Mad Monk (1966). In 1965 he directed The Face of Fu Manchu, based on the character created by Sax Rohmer, and starring Christopher Lee. Sharp also directed the sequel The Brides of Fu Manchu (1966). In the 1980s he was also responsible for several hugely popular miniseries adapted from the novels of Barbara Taylor Bradford.

Early Career

Early life

Sharp was born in Hobart, Tasmania, in 1921, according to official military records and his own claims, even though reference sources cite 1922 as his year of birth. He was the second of four children.

He attended St Virgil's College and began appearing regularly in theatre productions at the Playhouse Theatre in Hobart, where he trained under a young Stanley Burbury.[1] He later said this was prompted "by a desi re not to study to become an accountant, which is what my parents wanted for me."[2]

Among the plays Sharp appeared in were You Can't Take It With You and Our Town. He also directed a production of Stage Door.[3] He studied accountancy in the evenings but this was interrupted by war service.[2]

War Service

Sharp enlisted in the Royal Australian Air Force on 7 April 1941 and was transferred to Singapore. In addition to his military duties he appeared in radio and on stage with a touring English company. Among his radio performances were Escape and the Barretts of Wimpole Street. "The acting bug had definitely gotten hold of me," says Sharp, "and I did a bit of it while I was in the RAAF as well, in the odd moment."[2]

Sharp was invalided out before the city fell to the Japanese. He returned to Melbourne and recuperated at Heidelberg Hospital. He spent the majority of his war service in Melbourne, appearing in amateur theatre productions of "Quality Street" and "The Late Christopher Bean" as well as recorded broadcasts and ABC plays.

In early 1943 he moved to Hobart. He appeared in a theatre production of Interval by Sumner Locke Elliott, also serving as assistant director.[4][5] Following this he appeared in a theatre revue, Khaki Capers, notably in a sketch which figured a flag flown over the air force station in Singapore which Sharp had brought back with him.[6]

Sharp was discharged from the air force on 17 March 1944 at the rank of corporal.[7][8]

Acting career

After the war Sharp did not want to return to Hobart. He auditioned for and won an understudy's position in J. C. Williamson Limited version of the Broadway comedy Kiss and Tell ; when a bout of laryngitis injured one of the leads two weeks later, Sharp stepped into the role. He toured in the production from 1944-1945 then went on to appear in such plays as Arsenic and Old Lace (1945) and The Dancing Years. He worked for Morris West's production company in radio and played a small role in Smithy (1946), one of the few feature films shot in Australia at this time.[9]

Sharp also toured Japan performing for the occupying troops there. From Japan he went to London in 1948. ""I could have gone on with a theatrical career in Australia," says Sharp, "but what I really wanted was movies. So I went to England."[2]

Move to England

Arriving in England in 1948, Sharp got some stage work quickly "but I couldn't even get an appointment to see a casting director" for films.[2]

He was sharing a flat with an assistant director and they decided to make their own movie. He co-wrote Ha'penny Breeze (1950), with a fellow Australian, Frank Worth. Together with another man, Darcy Conyers, they formed a production company and raised finance to make the £8,000 film. Sharp also played a leading role, did the accounts and helped with the direction. The film was not a large hit but it was theatrically released.[10][11]

Sharp also got a small role in a British radio adaptation of Robbery Under Arms (1950).[12]

Sharp said "Shortly after, a number of influential film people made contact with me, but none of them offered me a job as an actor— they all asked if I would write for them!"[13]

Sharp was unable to cash in on Ha'penny Breeze as he came down with tuberculosis and spent two years in hospital.

When he recovered he got some acting roles in such films as The Planter's Wife (1952), Appointment in London (1953), The Cruel Sea (1953) and You Know What Sailors Are (1954).

He also played the character Stephen "Mitch" Mitchell in the 1953 British science fiction radio series, Journey into Space. He began to turn increasingly to writing and directing.[3] Sharp said his background as an actor was useful for his development as a director, in particular it developed his sense of timing:

You’ve got to know, for example, a thing I was taught early in theatre – if there's a scene in a movie, in a play, that always gets good laughs, on a good night, when there's a good and laughing audience, you’ll get laughs in the build-up to it, in the five or ten minutes beforehand, because it's a good audience who's appreciative of what's going on. On a bad night, when the audience are not laughing, increase your pace, get them at the point. And this teaches you a control of speed and how to control an audience. . . . Working with good actors, you get a feeling of timing with them; although sometimes the timing between them can be good but their overall pace, which is quite different, can be wrong – its context in the film, because of the situation in the film, perhaps there should be that little more urgency, therefore pace, in the scene.[14]

He worked on the screenplay to Background (1953). A new government-backed film company, Group Three, had a brief to support new talent and Sharp sold them an original script called Child's Play (1954). Group Three liked it and bought a story of Sharp's, originally called The Norfolk Story.[15] He turned this into a novel called Conflict of Wings (1954), the title under which it was filmed; Sharp collaborated on the screenplay with John Pudney.[16]

He and Pudney then wrote The Blue Peter (1955) for Group Three.[17] Sharp also directed second unit.

Director

Early Films

Child's Play and Blue Peter were children's films. Sharp turned director for The Stolen Airliner (1955) for the Children's Film Foundation, based on a script by Pudney.[13]

Sharp made some documentaries: As Old as the Windmill (1957), The Changing Life (1958), and Keeping the Peace (1959).

After directing second unit on Carve Her Name with Pride (1958) and Harry Black (1958), he wrote and directed The Golden Disc (1959), the first British rock 'n' roll movie – released a year before the Cliff Richard vehicle Expresso Bongo (1959) and a full two years ahead of Beat Girl (1960). It starred Mary Steele, who Sharp married two years earlier.

He wrote and directed another film for the Children's Film Foundation, The Adventures of Hal 5 (1959). He followed it with Linda (1960), a teen drama starring Carol White for Independent Artists, which went out as a support feature for Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1960) and is now considered a lost film. Then came a low-budget thriller, also for Independent Artists, The Professionals (1960), which screened on US TV as part of the Kraft Mystery Theatre.

He went into TV, doing episodes of Ghost Squad (1961–62) and The Human Jungle (1963).

He directed second unit on The Fast Lady (1962) for IA.

He directed Two Guys Abroad (1962) with George Raft, which was intended as a pilot for a TV series or as a B movie, but ended up not being released at all.

Hammer Films and Harry Alan Towers

Sharp received an offer from Tony Hinds of Hammer Films who had seen The Professionals and was looking for a director for Hammer's vampire movie The Kiss of the Vampire (1963). Sharp had never seen a horror movie before but agreed after watching several Hammer films.[18][13]

According to his obituary Sharp helped make an "atmospheric, suspenseful gothic horror and giving a depth to the characters that was sometimes missing in Hammer's other vampire productions."[3] The Kiss of the Vampire is now one of Hammer's highest regarded horrors; Sharp's New York Times obituary says "Not a few Hammer fans contend that "The Kiss of the Vampire" is one of the greatest Gothic horror movies ever made".[19]

The Kiss of the Vampire was shot in 1962. Sharp followed it with another teen movie in the vein of The Golden Disc, It's All Happening (1963), with Tommy Steele.[20]

He returned to Hammer for a swashbuckler, The Devil-Ship Pirates (1964). It starred Christopher Lee, who would make several movies with Sharp.[21]

Sharp followed it with another in the horror genre, Witchcraft (1964), for producer Robert L. Lippert. Sharp called it "a little four-week movie, very quickly done, but it received some lovely notices".[13]

He contributed to the script of Legend of a Gunfighter (1964) and spent several months directing second unit on Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines (1965).[21] Sharp sayd "I had to think very hard about going back to second unit after directing a half-dozen features— but it was so tempting, especially after my air force days. So I did it; and it was tremendously exciting, and a marvelous movie to work on."[13]

Sharp did find shooting footage with old airplanes very slow - "you're fortunate if you can get two set-ups in a day" so when it was over he asked his agent to get him any job. Lippert had a sequel to The Fly, Curse of the Fly (1965), and Sharp did it. "I'm afraid they'd pretty much run out of ideas," said Sharp who says he and the writer "both had the feeling, 'Oh dear, what a pity they're making another one'."[22]

Sharp reteamed with Lee for The Face of Fu Manchu (1965), produced by Harry Alan Towers. Sharp later said "I like Harry, a great deal... but Harry will get more kick out of making $5 in a slightly crooked and fast way, than he would making $100 legitimately; he's a dealer rather than a movie maker, and he enjoys getting the best part of a deal. But he does have a certain enthusiasm, and a sense of showmanship. In order to make a good film while work-ing with Harry, you have to be insistent."[22]

Fu Manchu was a big hit and led to four sequels; Sharp only directed the first of these, but he worked several more time for Towers who later said "I kept using Don because his films came in on budget and were without exception very successful. On top of that he was a most agreeable person of very good character – no tantrums – clear headed – resourceful; a gentleman too."[14]

The movie would give Sharp a reputation for action movies. He later stated his philosophy:

You can’t do big action sequences and then have flabby, everyday stuff round it. Those movies have got to have a feeling of latent energy in there. . . . You can’t do action sequences as an entity in themselves. They’ve got to be part of the way a whole movie is developing. You’ve got to have, apart from energy, a very good sense of editing, what a camera can do... a sense of timing... and an ability to have a visual of exactly what it's going to look like... Also, I enjoyed it.... some directors... didn’t get the same enjoyment out of it; it was a necessity rather than a pleasure. I always liked doing it, liked doing action .[14]

It was back to Hammer for Rasputin, the Mad Monk (1966), with Lee in the title role. Sharp disliked this experience working for Hammer as the budgets were being tightened.[23]

Sharp followed it with a spy spoof for Towers, Our Man in Marrakesh (1966), starring Tony Randall. For Towers he also made The Brides of Fu Manchu (1966), again with Lee.

Sharp then made two films shot in Ireland: The Violent Enemy (1967), a thriller about the IRA from a novel by Jack Higgins, and Jules Verne's Rocket to the Moon (1967), an adventure tale in the vein of Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines for Towers.

He returned to TV, directing some episodes of The Avengers (1968) and The Champions (1969), before writing and directing Taste of Excitement (1969), for the same producers as The Violent Enemy. Sharp was offered The Vengeance of She at Hammer but been unable to take the job.[24]

Puppet on a Chain

Sharp said he was "out of work for about a year"[14] when he got an offer to direct a boat chase sequence for Puppet on a Chain (1971), based on a novel by Alistair MacLean. The producers liked his work so much they hired him to shoot some additional footage. In 2007 Sharp said the film earned him a reputation as "The Doctor" and he was still getting royalties from the movie.[14]

Michael Carreras of Hammer asked Sharp to take over the Seth Holt who had died while directing Blood from the Mummy's Tomb (1971) but Sharp was unable as he had a contract to make a film for the producers of Puppet in Israel. That film was not made.[24] According to Filmink "it’s a great shame Sharp only worked with" Hammer three times "because he was one of their best ever directors."[25]

Sharp directed a pair of horror movies – Dark Places (1973), with Lee, and Psychomania (1973), the final movie of George Sanders. The latter has become a cult classic. He called it "great fun to do, especially after doing several films in a row like The Violent Enemy. It was a great change, geared for a younger audience as it was."[26]

Callan (1974) was a big screen adaptation of the TV series starring Edward Woodward (1967–72). It was followed by another thriller, Hennessy (1975), with Rod Steiger in the title role, as an IRA man out to assassinate Queen Elizabeth II.

In 1975 Sharp worked on producer Harry Saltzman's abandoned pet project The Micronauts, a "shrunken man" epic to have starred Gregory Peck and Lee Remick.[27]

Carreras offered Sharp the job of directing To the Devil a Daughter for Hammer and he was interested but Sharp ultimately pulled out due to dissatisfaction with the script.[24]

Sharp directed the fourth version of The Four Feathers (1978), made for American TV but released theatrically in some markets. He then directed the remake of The Thirty Nine Steps (1978), with Robert Powell (who had been in Four Feathers). Producer Greg Smith said he hired Sharp "because he's one of Britain's best action adventure directors and he was familiar with the period."[28]

He directed (and co-wrote) Bear Island (1979), an adventure tale from the novel by Alistair MacLean starring Richard Widmark, Donald Sutherland and Vanessa Redgrave. It was one of the most expensive Canadian films ever made and a box office flop.[29]

Later career

Sharp returned to TV with episodes of Hammer House of Horror (1980) ("Guardian of the Abyss") and QED (1982) (TV series).[24]

He had a big ratings success with the mini series A Woman of Substance (1984), based on the novel by Barbara Taylor Bradford, with Jenny Seagrove and Deborah Kerr.

After What Waits Below (1985) with Powell, he focused on television. Tusitala (1986) was an Australian mini series shot in Samoa. Hold the Dream (1986), was a mini-series sequel to Woman of Substance, with Jenny Seagrove reprising her role. Tears in the Rain (1988) was a TV movie from a novel by Pamela Wallace which gave an early starring role to Sharon Stone. Act of Will (1989) was another mini series based on a novel by Barbara Taylor Bradford, which starred Liz Hurley.

Personal life

Sharp married an Australian actress, Gwenda Wilson, in 1945 after appearing on stage with her in Kiss and Tell.[30][31] In 1956 he married actress Mary Steele.

Sharp died on 14 December 2011, after a short spell in hospital.[3] He was survived by Mary Steele,[32] two sons and a daughter. Another son, Massive Attack producer Jonny Dollar, predeceased him.

Filmography

As actor

- Smithy (1946)[9]

- Ha'penny Breeze (1950, also writer, producer) – Johnny Craig

- The Planter's Wife (1952) – Lieutenant Summers (uncredited)

- Appointment in London (1953) – Mid Upper Gunner (uncredited)

- The Cruel Sea (1953) – Lieutenant-Commander (final film role)

- You Know What Sailors Are (1954)

- Journey into Space (1953–54) (radio serial)

- The Red Planet (1954–55) (radio serial)

As writer only

- Background (1953)

- Conflict of Wings (1954) – also novel

- Child's Play (1954)

- Legend of a Gunfighter (1964)

2nd Unit director

- The Blue Peter (1955) – also script

- Carve Her Name with Pride (1958)

- The Fast Lady (1962)

- Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines (1965)

- Puppet on a Chain (1971) – also script

As director

- The Stolen Airliner (1955) – also script

- As Old as the Windmill (1957) (documentary)[33]

- The Changing Life (1958) (documentary)[34]

- Keeping the Peace (1959) (documentary)[35]

- The Golden Disc (1959) – also script

- The Adventures of Hal 5 (1959) – also script

- Linda (1960)

- The Professionals (1960)

- Ghost Squad (1961–62) (TV series)

- The Human Jungle (1963) (TV series) – episode "A Friend of the Serjeant Major"

- Two Guys Abroad (1962)

- It's All Happening (1963)

- The Kiss of the Vampire (1963)

- Witchcraft (1964)

- The Devil-Ship Pirates (1964)

- Curse of the Fly (1965)

- The Face of Fu Manchu (1965)

- Rasputin, the Mad Monk (1966)

- Our Man in Marrakesh (1966)

- The Brides of Fu Manchu (1966)

- The Violent Enemy (1967)

- Jules Verne's Rocket to the Moon (1967)

- The Avengers (1968) – episodes "Get-A-Way!", "The Curious Case of the Countless Clues", "Invasion of the Earthmen"

- The Champions (1969) (TV series) – episode "Project Zero"

- Taste of Excitement (1969) – also script

- Dark Places (1973) – also script

- Psychomania (1973)

- Callan (1974)

- Dark Places (1974)

- Hennessy (1975)

- The Four Feathers (1978)

- The Thirty Nine Steps (1978)

- Bear Island (1979) – also script

- Hammer House of Horror (1980)

- QED (1982) (TV series) – episode "The Limehouse Connection"

- A Woman of Substance (1984) (TV)

- What Waits Below (1985)

- Tusitala (1986) (mini-series)

- Hold the Dream (1986) (TV)

- Tears in the Rain (1988) (TV)

- Act of Will (1989) (TV)

Unmade projects

Sharp was announced for the following projects which were not made:

- Sleeper Awakens (circa 1967) from the novel by H. G. Wells with Christopher Lee and Vincent Price for Harry Alan Towers[36]

- Spaceborn – an action suspense story that was to start filming in 1972[37]

- Philby (circa 1977) – biopic of Kim Philby starring Michael Caine in the lead role supported by Nicol Williamson as Guy Burgess and Vanessa Redgrave as Philby's first wife[38]

Theatre credits

- The Man from Toronto (January 1940) – The Playhouse, Hobart – actor[39]

- You Can't Take It with You by Kaufman and Hart (April 1940) – The Playhouse, Hobart – actor[40]

- I Killed the Count by Alec Coppel (August 1940) – The Playhouse, Hobart – actor[41][42]

- Tonight at 8.30 – "Hands Across the Sea" and "Ways and Means" by Noël Coward (October 1940) – The Playhouse, Hobart – actor[43][44]

- Our Town by Thornton Wilder (March 1941) – The Playhouse, Hobart – actor[45]

- revue at Theatre Royal Hobart (April 1941) – actor[46]

- Dear Octopus (May 1941) – The Playhouse, Hobart – assistant producer[47]

- Quiet Wedding (June 1941) – The Playhouse, Hobart – actor[48]

- Silver Lining Revue (June 1941) – The Playhouse, Hobart – performer[49]

- Stage Door (mid 1941) – The Playhouse, Hobart – producer[8]

- The Barretts of Wimpole Street (late 1941) – Singapore – actor[8]

- Quality Street (1942) – Melbourne – actor[8]

- The Late Christopher Bean (1942) – Melbourne – actor[8]

- Interval by Sumner Locke Elliott (February 1943) – The Playhouse, Hobart – actor, assistant producer[50]

- Khaki Kapers musical revue (April 1943) – Theatre Royal, Hobart – contributing writer[51][52]

- The Amazing Dr Clitterhouse by Barre Lyndon (December 1944) – Comedy Theatre, Melbourne – actor[53]

- Kiss and Tell (1944–45) – national tour for J.C. Williamson Ltd – actor[31][54]

- Arsenic and Old Lace (1945) – national tour for J.C. Williamson Ltd – actor[55]

- The Dancing Years by Ivor Novello (June 1946) – His Majesty's Theatre, Melbourne[56]

References

- "CAST OF 35 IN "OUR TOWN"". The Mercury. CLIII (21, 923). Tasmania. 4 March 1941. p. 5. Retrieved 29 January 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- Midnight p 14

- Anthony Hayward, Don Sharp: Film director who made his mark with 'Kiss of the Vampire' from The Independent dated 29 December 2011, accessed 30 December 2011

- "THEATRICAL WORK ON SERVICE". The Mercury. CLVII (22, 517). Tasmania. 30 January 1943. p. 5. Retrieved 28 January 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- ""Interval"' Is Entertaining Play". The Mercury. CLVII (22, 524). Tasmania. 8 February 1943. p. 4. Retrieved 28 January 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- ""KHAKI KAPERS"". The Mercury. CLVII (22, 571). Tasmania. 3 April 1943. p. 4. Retrieved 28 January 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- "WW2 Nominal Roll". Ww2roll.gov.au. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- "THEATRICAL WORK ON SERVICE". The Mercury. Hobart, Tas. 30 January 1943. p. 5. Retrieved 24 March 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

- "FILM NOTES". The West Australian. Perth. 29 June 1945. p. 11. Retrieved 24 March 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

- "AUSSIES' "HOME-MADE MASTERPIECE"". The Sunday Herald (99). Sydney. 17 December 1950. p. 4 (Sunday Herald Features). Retrieved 28 January 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- "Australians in brave film bid". The Australian Women's Weekly. 18 (28). 16 December 1950. p. 49. Retrieved 28 January 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- "WORTH Reporting". The Australian Women's Weekly. 17 (37). 18 February 1950. p. 27. Retrieved 28 January 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- Midnight p 15

- Exshaw, John (20 January 2012). ""Don Sharp Director"". Cinema Retro. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- "Comedy is child's play to former actor". The Australian Women's Weekly. 20 (23). 5 November 1952. p. 54. Retrieved 28 January 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- "Australian's Novel As Film Success". The Sydney Morning Herald (36, 281). 3 April 1954. p. 3. Retrieved 28 January 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- "Beats English to it". Sunday Mail. Queensland. 18 April 1954. p. 14. Retrieved 28 January 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- Koetting p 8-9

- Martin, Douglas (23 December 2011). "Don Sharp Dies at 89; Director Who Revived Hammer Horror Film Company". New York Times.

- Koetting p 10

- Koetting p 11

- Midnight p 16

- Koetting p 11-12

- Koetting p 13

- Vagg, Stephen (28 June 2020). "Ten random Australian connections with Hammer Films". Filmink.

- Midnight p 18

- Trott, Walt (8 September 1975). "Bonds, Bugs and Ballyhoo". European Stars And Stripes. p. 19.

- Klemesrud, Judy (27 April 1980). "A New Film Version of 'The 39 Steps': Opening This Week 'The 39 Steps'". New York Times. p. D8.

- Adilman, Sid (11 March 1979). "Bear Island: The Film That Stayed out in the Cold". Los Angeles Times. p. m6.

- "THE LIFE OF MELBOURNE". The Argus (30, 713). Melbourne. 3 February 1945. p. 12. Retrieved 28 January 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- ""KISS AND TELL"". Kalgoorlie Miner. WA. 17 November 1945. p. 2. Retrieved 24 March 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

- "Mary Steele". IMDb. Retrieved 14 February 2020.

- As Old as the Windmill at BFI

- The Changing Life at BFI

- Keeping the Peace at BFI

- "Hunter Role for Sandra Dee" Martin, Betty. Los Angeles Times 13 January 1967: c12.

- "MOVIE CALL SHEET: Burglar Study to Be Filmed" Murphy, Mary. Los Angeles Times 31 July 1972: f14.

- "Don Sharp to direct 'Philby'." Times [London, England] 30 March 1977: 12. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 16 April 2014.

- "GLYNDEBOURNE FOR AUSTRALIA?". The Mercury. Hobart, Tas. 13 January 1940. p. 6. Retrieved 24 March 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

- ""YOU CAN'T TAKE IT WITH YOU"". The Mercury. Hobart, Tas. 29 April 1940. p. 10. Retrieved 24 March 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

- ""I KILLED THE COUNT" HAS GOOD PREMIERE". The Mercury. Hobart, Tas. 19 August 1940. p. 5. Retrieved 24 March 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

- "Realistic Acting in Repertory Play". The Mercury. Hobart, Tas. 24 August 1940. p. 5. Retrieved 24 March 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

- "MUSIC AND STAGE". The Mercury. Hobart, Tas. 5 October 1940. p. 5. Retrieved 24 March 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

- "NOEL COWARD PLAYS". The Mercury. Hobart, Tas. 14 October 1940. p. 5. Retrieved 24 March 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

- "CAST OF 35 IN "OUR TOWN"". The Mercury. Hobart, Tas. 4 March 1941. p. 5. Retrieved 24 March 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

- "SPARKLING REVUE". The Mercury. Hobart, Tas. 7 April 1941. p. 4. Retrieved 24 March 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

- "FAMILY COMEDY". The Mercury. Hobart, Tas. 5 May 1941. p. 4. Retrieved 24 March 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

- "ENTERTAINING PRODUCTION". The Mercury. Hobart, Tas. 23 June 1941. p. 6. Retrieved 24 March 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

- "SILVER LINING REVUE". The Mercury. Hobart, Tas. 28 July 1941. p. 4. Retrieved 24 March 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

- ""Interval"' Is Entertaining Play". The Mercury. Hobart, Tas. 8 February 1943. p. 4. Retrieved 24 March 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

- ""KHAKI KAPERS"". The Mercury. Hobart, Tas. 3 April 1943. p. 4. Retrieved 24 March 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

- "KHAKI KAPERS". The Mercury. Hobart, Tas. 9 April 1943. p. 5. Retrieved 24 March 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

- ""THE AMAZING DR CLITTERHOUSE"". The Argus. Melbourne. 26 December 1944. p. 5. Retrieved 24 March 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

- "Stage Stars Meet in Hospital". The Daily News. Perth. 17 November 1945. p. 12 Edition: FIRST EDITION. Retrieved 24 March 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

- "SATIRICAL COMEDY". The West Australian. Perth. 30 November 1945. p. 8. Retrieved 24 March 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

- ""Dancing Years" At His Majesty's on June 29". The Argus. Melbourne. 12 June 1946. p. 6. Retrieved 24 March 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

Sources

- Koetting, Christopher (1995). "Costume Dramas". Hammer Horror. pp. 7–13.

- The Midnight Writer (December 1983). "Sharp Turns". Fangoria. No. 31. pp. 14–18.

- Vagg, Stephen (27 July 2019). "Unsung Aussie Filmmakers: Don Sharp – A Top 25". Filmink.

External links

- Don Sharp on IMDb

- Obituary at The Guardian

- Obituary at Variety

- Obituary at New York Times

- Obituary from The Times with funeral arrangements.

- A Wasted Life: RIP Don Sharp

- "DON SHARP, DIRECTOR: AN APPRECIATION", Cinema Retro

- Don Sharp at Britmovie

- Don Sharp at AustLit