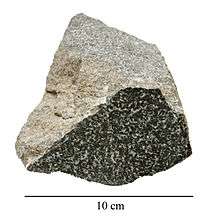

Diabase

Diabase ( /ˈdaɪ.əbeɪs/) or dolerite or microgabbro[1] is a mafic, holocrystalline, subvolcanic rock equivalent to volcanic basalt or plutonic gabbro. Diabase dikes and sills are typically shallow intrusive bodies and often exhibit fine grained to aphanitic chilled margins which may contain tachylite (dark mafic glass). Diabase is the preferred name in North America, while dolerite is the preferred name in the rest of English-speaking world, where sometimes the name diabase is applied to altered dolerites and basalts. Some geologists prefer the name microgabbro to avoid this confusion.

Petrography

Diabase normally has a fine but visible texture of euhedral lath-shaped plagioclase crystals (62%) set in a finer matrix of clinopyroxene, typically augite (20–29%), with minor olivine (3% up to 12% in olivine diabase), magnetite (2%), and ilmenite (2%).[2] Accessory and alteration minerals include hornblende, biotite, apatite, pyrrhotite, chalcopyrite, serpentine, chlorite, and calcite. The texture is termed diabasic and is typical of diabases. This diabasic texture is also termed interstitial.[3] The feldspar is high in anorthite (as opposed to albite), the calcium endmember of the plagioclase anorthite-albite solid solution series, most commonly labradorite.

Locations

Diabase is usually found in smaller relatively shallow intrusive bodies such as dikes and sills. Diabase dikes occur in regions of crustal extension and often occur in dike swarms of hundreds of individual dikes or sills radiating from a single volcanic center.

The Palisades Sill which makes up the New Jersey Palisades on the Hudson River, near New York City, is an example of a diabase sill. The dike complexes of the British Tertiary Volcanic Province which includes Skye, Rum, Mull, and Arran of western Scotland, the Slieve Gullion region of Ireland, and extends across northern England contains many examples of dolerite dike swarms, towards the Midlands other examples include Rowley Rag. Parts of the Deccan Traps of India, formed at the end of the Cretaceous also include dolerite.[4] It is also abundant in large parts of Curaçao, an island off the coast of Venezuela. Another example of diabase dikes has been recognized in the Mongo area within the Guéra Massif of Chad in Central Africa.[5]

In Western Australia a 200 km long dolerite dike, the Norseman–Wiluna Belt[6] is associated with the non-alluvial gold mining area between Norseman and Kalgoorlie, which includes the largest gold mine in Australia,[7] the Super Pit gold mine. West of the Norseman–Wiluna Belt is the Yalgoo–Singleton Belt, where complex dolerite dike swarms obscure the volcaniclastic sediments.[8] Large dolerite sills such as the Golden Mile Dolerite can exhibit coarse grained texture, and show a large diversity in petrography and geochemistry across the width of the sill.[9] Early Jurassic activity resulted in the formation of dolerite intrusion on Prospect Hill in Sydney[10], and quarrying of basalt for roadstone and other building materials has been an important activity there for over 180 years.[11][12]

In the Thuringian-Franconian-Vogtland Slate Mountains of central Germany the diabase is entirely of Devonian age.[13] They form typical domed landscapes, especially in the Vogtland. One geotourist attraction is the Steinerne Rose near Saalburg, a natural monument, whose present shape is due to the typical weathering of lava pillows.

The vast areas of mafic volcanism/plutonism associated with the Jurassic breakup of Gondwanaland in the Southern Hemisphere include many large diabase/dolerite sills and dike swarms. These include the Karoo dolerites of South Africa, the Ferrar Dolerites of Antarctica, and the largest of these, indeed the most extensive of all dolerite formations worldwide, are found in Tasmania. Here, the volume of magma which intruded into a thin veneer of Permian and Triassic rocks from multiple feeder sites, over a period of perhaps a million years, may have exceeded 40,000 cubic kilometres.[14] In Tasmania, dolerite dominates much of the landscape, particularly alpine areas.

In the Death Valley region of California, precambrian diabase intrusions metamorphosed pre-existing dolomite into economically important talc deposits.[15]

Use

Diabase is crushed and used as a construction aggregate for road beds, buildings, railroad beds (rail ballast), and within dams and levees.[16][17]

Diabase can be cut for use as headstones and memorials; the base of the Marine Corps War Memorial is made of black diabase "granite" (a commercial term, not actual granite). Diabase can also be cut for use as ornamental stone for countertops, facing stone on buildings, and paving.[17] A form of dolerite, known as bluestone, is one of the materials used in the construction of Stonehenge.[18]

Diabase also serves as local building stone. In Tasmania, where it is one of the most common rocks found,[19] it is used for building, for landscaping and to erect dry-stone farm walls. In northern County Down, Northern Ireland, "dolerite" is used in buildings such as Mount Stewart together with Scrabo Sandstone as both are quarried at Scrabo Hill.

The Blackbird (violin) is made of black diabase.

See also

References

- "BGS Rock Classification Scheme - Dolerite (Synonymous with Microgabbro)". British Geological Survey. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

- Klein, Cornelus and Cornelius S. Hurlbut, Jr.(1986) Manual of Mineralogy, Wiley, 20th ed., p. 483 ISBN 0-471-80580-7

- Morehouse, W. W. (1959) The Study of Rocks in Thin Section, Harper & Row, p. 160

- Continental Flood Basalts (and Layered Intrusions)

- Nkouandou, Oumarou Faarouk; Bardintzeff, Jacques-Marie; Mahamat, Oumar; Fagny Mefire, Aminatou; Ganwa, Alembert Alexandre (2017-05-22). "The dolerite dyke swarm of Mongo, Guéra Massif (Chad, Central Africa): Geological setting, petrography and geochemistry". Open Geosciences. 9 (1): 138–150. Bibcode:2017OGeo....9...12N. doi:10.1515/geo-2017-0012. ISSN 2391-5447.

- Hill R.E.T, Barnes S.J., Gole M.J., and Dowling S.E., 1990. Physical volcanology of komatiites; A field guide to the komatiites of the Norseman-Wiluna Greenstone Belt, Eastern Goldfields Province, Yilgarn Block, Western Australia., Geological Society of Australia. ISBN 0-909869-55-3

- O'Connor-Parsons, Tansy; Stanley, Clifford R. (2007). "Downhole lithogeochemical patterns relating to chemostratigraphy and igneous fractionation processes in the Golden Mile dolerite, Western Australia". Geochemistry: Exploration, Environment, Analysis. 7 (2): 109–27. doi:10.1144/1467-7873/07-132.

- Wanga Q.; Campbella I. H. (1998). "Geochronology of supracrustal rocks from the Golden Grove area, Murchison Province, Yilgarn Craton, Western Australia". Australian Journal of Earth Sciences. 45 (4): 571–77. Bibcode:1998AuJES..45..571W. doi:10.1080/08120099808728413.

- Travis, G.A.; Woodall, R.; Bartram, G.D. (1971), "The Geology of the Kalgoorlie Goldfield", in Glover, J.E. (ed.), Symposium on Archaean Rocks, Geological Society of Australia (Special Publication 3), pp. 175–190

- Jones, I., and Verdel, C. (2015). Basalt distribution and volume estimates of Cenozoic volcanism in the Bowen Basin region of eastern Australia: Implications for a waning mantle plume. Australian Journal of Earth Sciences, 62(2), 255–263.

- Robert Wallace Johnson (24 November 1989). Intraplate Volcanism: In Eastern Australia and New Zealand. Cambridge University Press. pp. 4–. ISBN 978-0-521-38083-6.

- Wilshire, H.G. (1967) The Prospect Alkaline Diabase-Picrite Intrusion New South Wales, Australia. Journal of Petrology 8(1) pp.97-163.

- Henningsen, Dierk; Katzung, Gerhard (2006). Einführung in die Geologie Deutschlands (in German) (7th ed.). Munich: Spektrum Akademischer Verlag. p. 69. ISBN 3-8274-1586-1.

- Leaman, David 2002, "The Rock that Makes Tasmania", Leaman Geophysics, ISBN 0-9581199-0-2 p. 117.

- Miller, MB, and Wright, LA. 2007, "Geology of Death Valley National Park (Third Edition)", Kendall Hunt Publishing, p 19.

- Allen, George (Spring 2004). "Clayton Quarry". Mount Diablo Interpretive Association. Archived from the original on 2017-11-16. Retrieved 2017-03-30.

- "Diabase Rock". comparerocks.com. Archived from the original on 2017-03-31. Retrieved 2017-03-30.

- John, Brian S.; Jackson Jr., Lionel E. (31 December 2008). "Stonehenge's Mysterious Stones". Earth magazine. American Geosciences Institute. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- "Tasmanian Viticultural Soils and Geology" (PDF). Tasmania Department of Primary Industries, Water and Environment / University of Tasmania / Tasmanian Institute of Agricultural Research. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Diabase. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Diabase. |