Guard (grappling)

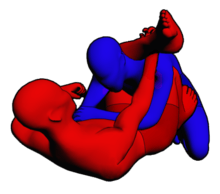

The guard is a ground grappling position in which one combatant has their back to the ground while attempting to control the other combatant using their legs. In pure grappling combat sports, the guard is considered an advantageous position, because the bottom combatant can attack with various joint locks and chokeholds, while the top combatant's priority is the transition into a more dominant position, a process known as passing the guard. In the sport of mixed martial arts, as well as hand-to-hand combat in general, it is possible to effectively strike from the top in the guard, even though the bottom combatant exerts some control. There are various types of guard, with their own advantages and disadvantages.

| Guard | |

|---|---|

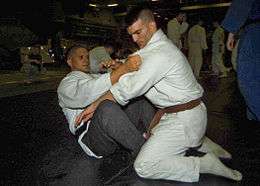

.jpg) Standard closed guard, demonstrated by US Army Rangers. | |

| Classification | Position |

| Style | Jujutsu, Judo, Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu |

| Child hold(s) | closed guard, open guard, half guard |

The guard is a key part of Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu where it can be used as an offensive position. It is also used, but not formally named, in Judo[1] though it is sometimes referred to as dō-osae in Japanese, meaning "trunk hold".[2][note 1] It is called the "front body scissor" in catch wrestling.

Pulling Guard

Transitioning directly from standing to the guard position is known as pulling guard. Tsunetane Oda, a judo groundwork specialist who died in 1955,[3] demonstrated the technique on video.[4]

Closed Guard

Sometimes referred to as full guard, the closed guard is the typical guard position. In this guard the legs are hooked behind the back of the opponent, preventing them from standing up or moving away. The opponent needs to open the legs up to be able to improve positioning. The bottom combatant might transit between the open and closed guard, as the open guard allows for better movement, but also has a bigger risk of the opponent passing the guard.

Open Guard

The open guard is typically used to perform various joint locks and chokeholds. The legs can be used to move the opponent, and to create leverage. The open guard allows the opponent to stand up or try to pass the guard, so this position is often used temporarily to set up sweeps or other techniques. Open guard is also a general term that encompasses a large number of guard positions where the legs are used to push, wrap or hook the opponent without locking the ankles together around them.

Butterfly Guard

The butterfly guard involves both of the legs being hooked with the ankles in between the opponents legs, against the inside of the opponents thighs. The opponent is controlled using both legs and arms. The leverage in the butterfly guard allows powerful sweeps. The guard also allows one to elevate or set the opponent off balance and because of this it is particularly useful in avoiding damage and allows transitions to other dominant positions. The analogous technique in wrestling and catch wrestling is called double elevator.

X-Guard

The X-guard is an open guard where one of the combatants is standing up and the other is on their back. The bottom combatant uses the legs to entangle one of the opponent's legs, which creates opportunities for powerful sweeps. The X-guard is often used in combination with butterfly and half guard. In a grappling match, this is an advantageous position for the bottom combatant, but in general hand-to-hand combat, the top combatant can attack with stomps or soccer kicks. Likewise, skilled use of the x-guard can prevent the opponent from attempting a kick, or throw them off balance should they raise a leg. For instance, in the first round of the UFC196 fight between Conor McGregor and Nate Diaz, McGregor used the x-guard to sweep Diaz after Diaz stood in McGregor's butterfly guard.[5] The x-guard has been used in Judo[6] before being popularised by Marcelo Garcia.[7]

Spider Guard

The spider guard comprises a number of positions all of which involve controlling the opponents arms while using the soles of the feet to control the opponent at the biceps, hips, thighs or a combination of them. It is most effective when the sleeves of the opponent can be grabbed. The spider guard can be used for sweeps and to set up joint locks or chokeholds.

Jimahiva Guard

The Jimahiva guard (also called the Jimahiva hook and jello guard) is an open guard that has been used in Judo[8] before being popularized in Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu by white belt Jiminho, who was successful with it in competition. The guard consists of one of the legs wrapped behind the opponent's leg from the outside, the ankle held with one hand, and the other hand grips one of their sleeves. The Jimahiva guard offers a number of sweeps, transitions and submissions, and is more recently used in combination with spider guard.

Rubber Guard

The rubber guard a position that keeps an opponent down in your guard. Similar positions have been seen in Judo[9] before being commonly used in Brazilian jiu-jitsu by Nino Schembri, then popularized and made a system by Eddie Bravo. Many techniques have been developed from this position including sweeps, submissions, and striking defense. By using a leg to hold an opponent down, one arm is free to work on submissions, sweeps or to strike the opponent's trapped head.

50-50 Guard

The 50-50 (Fifty-fifty) guard is a position popularized by Roberto “Gordo” Correa and extensively used by the Mendes Brothers, Rafael and Guilherme Mendes, Bruno Frazzato, Ryan Hall and Ramon Lemos from the Atos Jiu-Jitsu Team. In other grappling systems such as catch wrestling and Sambo, it is a form of the "outside leg triangle" type of leg control. In this position, the fighter on the bottom crosses a triangle on the opponent's leg, which allows for the leg to be dominated while leaving the arms free to work on sweeps and submissions. This position has been heavily criticized for use in competitions with restricted use of leglocks due to the potential of stalling a match when the fighter on top cannot pass the guard and the fighter on the bottom cannot successfully perform a sweep.[10][11][12][13][14][15][16]

Passing the Guard

In order to overcome the primary defense of one's opponent, their guard, and attain a more dominant position, such as side mount, full mount, or knee on stomach a practitioner must pass the guard. There are several ways of doing so; many involve pain compliance whereby the practitioner persuades the opponent to release their guard through an abrasive action. Examples of this type of action would be digging the practitioner's forearms into the inner thigh of the opponent, standing and attempting a can opener neck crank, or in the case of a mixed martial arts setting, to simply strike the opponent until the guard is released. Passing the guard however has perils of its own, as it has a tendency to leave the practitioner particularly vulnerable to counterattack in the form of sweeps and submissions.

Simple guard pass

Simple guard pass also known as the arm/leg pull is a guard pass demonstrated in The Essence Of Judo by Kyuzo Mifune, and it is an unnamed technique described in The Canon Of Judo.[17] In Brazilian Jiu Jitsu this pass is commonly referred to as the Toreando/Bull Fighter Pass.[18] The main characteristic of the pass is the practitioner side-stepping around the opponent's legs whilst simultaneously pulling aside the opponent's leg or pinning the opponents legs to the ground.

Stacking guard pass

Stacking Guard Pass is also demonstrated in The Essence Of Judo by Mifune, and it is also an unnamed technique described in The Canon Of Judo.[17] The main characteristic of the technique is the practitioner lifting the opponent and stacking them, into a possible neck crank or blood choke submission, when the practitioner is in the opponent's open guard.

Near knee guard pass

Near Knee Guard Pass is also demonstrated in The Essence Of Judo by Mifune as well as Canon of Judo by Mifune.[19] In Brazilian Jiu Jitsu, this guard pass is commonly referred to as the Knee Over Pass.[20] The main characteristic of this pass is the practitioner driving their knee over the opponent's same side thigh while in the opponent's open guard.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Guard (grappling). |

- Half guard

- Grappling

- Grappling hold

- Brazilian Jiu-jitsu

- Judo

Footnotes

- The technique "do-jime" is sometimes incorrectly used to describe the closed guard. The difference is that with do-jime, pressure is applied to squeeze the opponent's trunk to cause asphyxia. Do-jime is a prohibited technique in judo, see IJF Referee Rules (English version).

References

- Jimmy Pedro. The Pedro Guard Pass by Jimmy Pedro Archived 2010-05-19 at the Wayback Machine

- Miller, Chris. Grappling/Submission Fighting. hsma1.com. URL last accessed on March 4, 2006.

- Toshikazu Okada. Master Tsunetane Oda

- Tsunetane Oda - judo ne-waza 2 of 3

- Kohn, Benjamin (January 19, 2020). "Analyzing the Grappling of Conor McGregor at UFC 196". thefight-site.com. The Fight Site. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

With both feet completely secured by Conor, Nate gets elevated as Conor starts to extend with his legs, completing the (admittedly not perfectly done) x-guard sweep.

- Okano, Isao (1976). Vital Judo: Grappling Techniques. Japan Publications. pp. 132–133. ISBN 978-0870405174.

- Garcia, Marcelo; Eric Hendrikx; Glen Cordoza; Erich Krauss (2008). The X-Guard: Gi & No Gi Jiu-Jitsu. Sport Series (illustrated ed.). Tuttle Publishing. p. 260. ISBN 0-9777315-0-2.

- RH Marcus-Lohan (2014-12-08), Tsunetane Oda - Kosen Judo 'Jimahiva sweep', early 1900s, France, retrieved 2018-09-26

- Kawaishi, Mikinosuke (1960). Ma méthode de judo (2nd ed.). Judo - International. p. 195.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-08-30. Retrieved 2009-09-13.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-09-07. Retrieved 2009-09-13.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-08-31. Retrieved 2009-09-13.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-09-28. Retrieved 2009-09-13.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-09-18. Retrieved 2009-09-13.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-08-29. Retrieved 2009-09-13.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-09-04. Retrieved 2009-09-13.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Mifune, Kyuzo. The Canon Of Judo. Kodansha International Ltd. ISBN 4-7700-2979-9.

- Smith, Andrew (March 29, 2019). "7 Toreando Guard Pass Variations in Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu". How They Play. How They Play. Retrieved March 21, 2020.

- Mifune, Kyuzo (1958). Canon of Judo. Tokyo, Japan: Seibundo Shinkosha Publishing Co. p. 174.

- "The Knee Over Pressure Pass". BJJ Fanatics. BJJ Fanatics. Retrieved April 10, 2020.

Further reading

- Løvstad, Jakob. The Mixed Martial Arts Primer. www.idi.ntnu.no. URL last accessed March 6, 2006. (DOC format)

- Page, Nicky. Groundfighting 101. homepage.ntlworld.com. URL last accessed March 4, 2006.

- Kesting, Stephan. The X guard position. www.grapplearts.com. URL last accessed March 7, 2006.

- Bravo, Eddie (2006) Mastering The Rubber Guard. ISBN 0-9777315-9-6