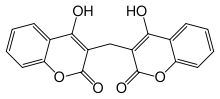

Dicoumarol

Dicoumarol (INN) or dicumarol (USAN) is a naturally occurring anticoagulant drug that depletes stores of vitamin K (similar to warfarin, a drug that dicoumarol inspired). It is also used in biochemical experiments as an inhibitor of reductases.

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| MedlinePlus | a605015 |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | plasmatic proteins |

| Metabolism | hepatic |

| Excretion | faeces, urine |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| NIAID ChemDB | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.575 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C19H12O6 |

| Molar mass | 336.299 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Dicoumarol is a natural chemical substance of combined plant and fungal origin. It is a derivative of coumarin, a bitter-tasting but sweet-smelling substance made by plants that does not itself affect coagulation, but which is (classically) transformed in mouldy feeds or silages by a number of species of fungi, into active dicoumarol. Dicoumarol does affect coagulation, and was discovered in mouldy wet sweet-clover hay, as the cause of a naturally occurring bleeding disease in cattle.[1] See warfarin for a more detailed discovery history.

Identified in 1940, dicoumarol became the prototype of the 4-hydroxycoumarin anticoagulant drug class. Dicoumarol itself, for a short time, was employed as a medicinal anticoagulant drug, but since the mid-1950s has been replaced by its simpler derivative warfarin, and other 4-hydroxycoumarin drugs.

It is given orally, and it acts within two days.

Uses

Dicoumarol was used, along with heparin, for the treatment of deep venous thrombosis. Unlike heparin, this class of drugs may be used for months or years.

Mechanism of action

Like all 4-hydroxycoumarin drugs it is a competitive inhibitor of vitamin K epoxide reductase, an enzyme that recycles vitamin K, thus causing depletion of active vitamin K in blood. This prevents the formation of the active form of prothrombin and several other coagulant enzymes. These compounds are not antagonists of Vitamin K directly—as they are in pharmaceutical uses—but rather promote depletion of vitamin K in bodily tissues allowing vitamin K's mechanism of action as a potent medication for dicoumarol toxicity. The mechanism of action of Vitamin K along with the toxicity of dicoumarol are measured with the prothrombin time (PT) blood test.

Poisoning

Overdose results in serious, sometimes fatal uncontrolled hemorrhage.[2]

History

Dicoumarol was isolated by Karl Link's laboratory at University of Wisconsin, six years after a farmer had brought a dead cow and a milk can full of uncoagulated blood to an agricultural extension station of the university. The cow had died of internal bleeding after eating moldy sweet clover; an outbreak of such deaths had begun in the 1920s during The Great Depression as farmers could not afford to waste hay that had gone bad.[3] Link's work led to the development of the rat poison warfarin and then to the anticoagulants still in clinical use today.[3]

Footnotes

- Nicole Kresge; Robert D. Simoni; Robert L. Hill (2005-02-25). "Sweet clover disease and warfarin review". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 280 (8): e5. Retrieved 2012-09-26.

- Duff, I. F.; Shull, W. H. (1949). "Fatal Hemorrhage in Dicumarol® Poisoning". Journal of the American Medical Association. 139 (12): 762–6. doi:10.1001/jama.1949.02900290008003. PMID 18112552.

- Wardrop, Douglas; Keeling, David (2008). "The story of the discovery of heparin and warfarin" (PDF). British Journal of Haematology. 141 (6): 757–763. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07119.x. PMID 18355382.

See also

References

- Cullen J, Hinkhouse M, Grady M, Gaut A, Liu J, Zhang Y, Weydert C, Domann F, Oberley L (2003). "Dicumarol inhibition of NADPH: quinone oxidoreductase induces growth inhibition of pancreatic cancer via a superoxide-mediated mechanism". Cancer Res. 63 (17): 5513–20. PMID 14500388.

- Mironov A, Colanzi A, Polishchuk R, Beznoussenko G, Mironov A, Fusella A, Di Tullio G, Silletta M, Corda D, De Matteis M, Luini A (2004). "Dicumarol, an inhibitor of ADP-ribosylation of CtBP3/BARS, fragments golgi non-compact tubular zones and inhibits intra-golgi transport". Eur J Cell Biol. 83 (6): 263–79. doi:10.1078/0171-9335-00377. PMID 15511084.

- Abdelmohsen K, Stuhlmann D, Daubrawa F, Klotz L (2005). "Dicumarol is a potent reversible inhibitor of gap junctional intercellular communication". Arch Biochem Biophys. 434 (2): 241–7. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2004.11.002. PMID 15639223.

- Thanos C, Liu Z, Reineke J, Edwards E, Mathiowitz E (2003). "Improving relative bioavailability of dicumarol by reducing particle size and adding the adhesive poly(fumaric-co-sebacic) anhydride". Pharm Res. 20 (7): 1093–100. doi:10.1023/A:1024474609667. PMID 12880296.]