Diary of a Country Priest

Diary of a Country Priest (French: Journal d'un curé de campagne) is a 1951 French drama film written and directed by Robert Bresson, and starring Claude Laydu. It was closely based on the novel of the same name by Georges Bernanos. Published in 1936, the novel received the Grand prix du roman de l'Académie française. It tells the story of a young sickly priest who has been assigned to his first parish, a village in northern France.

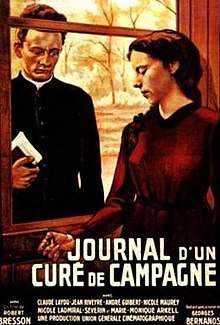

| Diary of a Country Priest | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Robert Bresson |

| Produced by | Léon Carré Robert Sussfeld |

| Written by | Robert Bresson |

| Based on | The Diary of a Country Priest 1936 novel by Georges Bernanos |

| Starring | Claude Laydu Jean Riveyre André Guibert |

| Music by | Jean-Jacques Grünenwald |

| Cinematography | Léonce-Henri Burel |

| Edited by | Paulette Robert |

| Distributed by | Brandon Films Inc. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 115 minutes |

| Country | France |

| Language | French |

Diary of a Country Priest was lauded for Laydu's debut performance, which has been called one of the greatest in the history of cinema; the film won numerous awards, including the Grand Prize at the Venice International Film Festival, and the Prix Louis Delluc.[1]

Plot

An idealistic young priest arrives at Ambricourt, his new parish. He is not welcome. The girls of the catechism class laugh at him in a prank, whereby only one of them pretends to know the Scriptural basis of the Eucharist so that the rest of them can laugh at their private conversation. His colleagues criticize his diet of bread and wine, and his ascetic lifestyle. Concerned about Chantal, the daughter of the Countess, the priest visits the Countess at the family chateau, and appears to help her resume communion with God after a period of doubt. The Countess dies during the following night, and her daughter spreads false rumors that the priest's harsh words had tormented her to death. Refusing confession, Chantal had previously spoken to the priest about her hatred of her parents.

The older priest from Torcy talks to his younger colleague about his poor diet and lack of prayer, but the younger man seems unable to make changes. After his health worsens, the young priest goes to the city to visit a doctor, who diagnoses him with stomach cancer. The priest goes for refuge to a former colleague, who has lapsed and now works as an apothecary, while living with a woman outside wedlock. The priest dies in the house of his colleague after being absolved by him.

Cast

- Claude Laydu as Priest of Ambricourt

- Jean Riveyre as Count (Le Comte)

- Adrien Borel as Priest of Torcy (Curé de Torcy) (as Andre Guibert)

- Rachel Bérendt as Countess (La Comtesse) (as Marie-Monique Arkell)

- Nicole Maurey as Miss Louise

- Nicole Ladmiral as Chantal

- Martine Lemaire as Séraphita Dumontel

- Antoine Balpêtré as Dr. Delbende (Docteur Delbende) (as Balpetre)

- Jean Danet as Olivier

- Gaston Séverin as Canon (Le Chanoine) (as Gaston Severin)

- Yvette Etiévant as Femme de ménage

- Bernard Hubrenne as Priest Dufrety

- Léon Arvel as Fabregars

Production

Two other French scriptwriters, Jean Aurenche and Pierre Bost, had wanted to make film adaptations of the novel. Bernanos rejected Aurenche's first draft. By the time Bresson worked on the screenplay, Bernanos had died. Bresson said he "would have taken more liberties," if Bernanos were still alive.[2]

This film marked a transition period for Bresson, as he began using non-professional actors (with the exception of the Countess). It was also the first film in which Bresson utilized a complex soundtrack and voice-over narration, stating that "an ice-cold commentary can warm, by contrast, tepid dialogues in a film. Phenomenon analogues to that of hot and cold in painting."[3]

Guy Lefranc was assistant director on the movie.

Analysis

The film is a blending of dialogue and commentary, founded on the interior voice of the priest. Faithful to the spirit of Georges Bernanos, the author of Journal d'un curé de campagne, Bresson strips the story open thoroughly by composing a sequence of exemplary sobriety. At such a point could François Truffaut say that the film, which he particularly admired, had sound scenes that were "down-to-earth." (Bresson limits the most possible expressions and intonations of professional comedians; thus, for this sequence, he did not work elsewhere with amateurs, which he called "models"). Forcing himself a remarkable distance from relation to his subject who is "a man who limits perpetual states of the soul," he refuses all melodramatic effects and all mystic interpretations.

A profoundly religious and Christian film, Diary of a Country Priest is also the exploration of being a rebel of prey to a fixed idea, a theme that is consistent in the work of Bresson. Absent of all "psychologism," like all judgement of value, the director uniquely raises a question to something of significance to himself, thereby making Diary of a Country Priest a captivating and mysterious work.

Reception

Diary of a Country Priest was a financial success in France and established Bresson's international reputation as a major film director. Film critic André Bazin wrote an entire essay on the film, calling it a masterpiece "because of its power to stir the emotions, rather than the intelligence."[4] Claude Laydu's debut performance in the title role has been described as one of the greatest in the history of film. Jean Tulard, in his Dictionary of Film, wrote of him in this work, "No other actor deserves to go to heaven as much as Laydu."[5]

Diary of a Country Priest continues to receive high praise today. On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film has a 95% approval rating based on 37 critics, with an average rating of 8.7/10.[6] French journalist Frédéric Bonnaud praised Bresson's minimalist approach to the film's setting and argued, "For the first time in French cinema, the less the environment is shown, the more it resonates [...] ubiquitous and constant, persistent and unchanging, it doesn’t need to be shown: its evocation through sound is enough. It’s a veritable prison."[7] American director Martin Scorsese said the film influenced his own Taxi Driver (1976).[8] Several reviewers of the 2017 film First Reformed noted that writer and director Paul Schrader appeared to be heavily influenced by the film.[9][10][11]

Awards

The film won eight international awards, including the Grand Prize at the Venice International Film Festival, and the Prix Louis Delluc.[12]

References

- Wakeman. pp. 57.

- François Truffaut, "A Certain Tendency of the French Cinema" Film Theory: Critical Concepts in Media and Cultural Studies ed. Philip Simpson. New York: Taylor & Francis (2004): 11

- Wakeman, John. World Film Directors, Volume 1. The H. W. Wilson Company. 1987. pp. 57.

- Wakeman. pp. 57.

- Robert Bergan, "Claude Laydu obituary", The Guardian, 7 August 2011, accessed 15 June 2014

- "Diary of a Country Priest (Journal d'un curé de campagne) (1954)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- Bonnaud, Frédéric (2 February 2004). "Diary of a Country Priest - From the Current". Film Comment. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- Martin Scorsese: Interviews, ed. Peter Brunette. Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi (1999): 67. "Don't forget that is what the priest is doing in Diary of a Country Priest."

- https://www.theringer.com/movies/2018/5/20/17373504/first-reformed-ethan-hawke-review

- http://www.ncregister.com/daily-news/sdg-reviews-first-reformed

- https://www.vox.com/summer-movies/2018/5/25/17384654/first-reformed-review-paul-schrader-ethan-hawke-christian-movie

- Wakeman. pp. 57.

Further reading

- Tibbetts, John C., and James M. Welsh, eds. The Encyclopedia of Novels Into Film (2nd ed. 2005) pp 98–99.

External links

- Diary of a Country Priest on IMDb

- Diary of a Country Priest at AllMovie

- Diary of a Country Priest at the TCM Movie Database

- Diary of a Country Priest at Rotten Tomatoes

- Voted #11 on The Arts and Faith Top 100 Films (2010)

- Diary of a Country Priest an essay by Frédéric Bonnaud at the Criterion Collection