Destiny (wordless novel)

Destiny (German: Schicksal) is the only wordless novel by German artist Otto Nückel. It first appeared in 1926 from the Munich-based publisher Delphin-Verlag. In 190 wordless images the story follows an unnamed woman in a German city in the early 20th century whose life of poverty and misfortune drives her to infanticide, prostitution, and murder.

The book was the first whose images were made with leadcuts instead of the more common woodcuts, and showed a greater depth of character and cinematic sense than previous wordless novels. The book inspired American artist Lynd Ward to tackle the medium, beginning with Gods' Man in 1929. Ward's success brought about an American publication of Destiny in 1930 which sold well. The book has impressed critics and has become one of the best-known wordless novels.

Synopsis

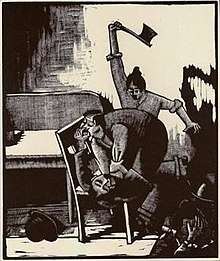

The book follows an unnamed woman in a German city in the early 20th century who lives a life of poverty and misfortune.[1] She is the constant victim of her society—especially the men, such as her drunken, abusive father, and the traveling salesman who gets her pregnant. She is imprisoned for the murder of her unwanted child, and upon release turns to life as a prostitute. The police hunt her down after she murders a man with an axe, and as she jumps from an upper-floor window they shoot her dead.[2]

Background

_Die_Passion_Eines_Menschen_8.jpg)

From 25 Images of a Man's Passion, 1918

Otto Nückel (1888–1955) was born in Cologne in the German Empire. He studied medicine in Freiburg before switching to art, which he studied in Munich in 1910–12.[3] His paintings were less successful than the illustrations he made for magazines such as the satirical Simplicissimus and for books by Thomas Mann and E. T. A. Hoffmann.[4]

In 1918, the Belgian Frans Masereel created the first wordless novel, 25 Images of a Man's Passion,[lower-alpha 1] and followed it up the next year with his longest and most successful work, Passionate Journey.[lower-alpha 2] Such books achieved particular popularity in Germany, where they sold in the hundreds of thousands in the 1920s. Masereel's woodcut artwork drew inspiration from the German Expressionists and displayed socialist themes of struggle against social injustice, themes that were to be common in the wordless novel genre.[5]

Production and publication

Nückel's medium was the leadcut—engraved plates of lead—a medium Nückel turned to when he found wood in short supply in Germany.[2] Lead plates are also more economical than wood in that they can be melted down and reused if errors are made during engraving.[6] Destiny was the first wordless novel to employ lead engraving.[2] Nückel made 190 prints[7] in black and white for the book.[2] The images range in size from 2 3⁄4 × 2 3⁄4 inches (7 × 7 cm) to 4 3⁄4 × 4 inches (12 × 10 cm)[8] and were originally printed on 197-×-172-millimetre (7.8 × 6.8 in) pages of thin Japanese handmade paper[7] when the book was published in Germany in 1926.[9]

Editions

- Das Schicksal: eine Geschichte in Bildern (1926). Munich: Delphin-Verlag[10]

- Destiny: A Novel in Pictures (1930). New York: Farrar & Rinehart[10]

- Schicksal eine Geschichte in Bildern (1984). Zürich: Limmat Verlag Genossenschaft[10]

- Destin (2005). Paris: Éditions IMHO[10]

- Destiny: A Novel in Pictures (2007). New York: Dover Publications[10]

Style and analysis

Self-portrait, 1920

Nückel engraved his plates with a multiple tool (also called a lining tool), a sort of chisel that cuts multiple parallel lines at once, which gives a mechanical hatching texture to the print.[11] The images vary not only in dimensions but in focus, from close-ups of faces to panoramas of crowds.[4]

In contrast to the earlier works of Masereel, Destiny focuses on an individualized woman instead of the plight of a man as cipher for humankind.[1] Lynd Ward found Nückel's book had greater psychological depth in its characters and plot development, and more skilled technical achievement in the artwork. Canadian artist George Walker believed that Masereel's plots were more original.[6]

Reception and legacy

American artist Lynd Ward discovered a copy of Nückel's book in New York in 1929 and was inspired by it to create wordless novels of his own, beginning with Gods' Man the same year.[12] The success of both Gods' Man and the subsequent Madman's Drum (1930) led to a number of American publishers bringing other wordless novels into print, including Destiny in 1930,[13] which sold well in the US.[14]

Literary scholar Martin S. Cohen called Destiny "perhaps the most pathetic ... and one of the most memorable" examples of the wordless novel genre.[14] Wordless novel scholar David Beronä judged the book "a pioneering work in the development of the contemporary graphic novel" for the complexity of its plot, its social consciousness, and its focus on an individual character.[15] Reviewer Christian Gasser commended the book's "narrative pull", which he credited as creating a "haunting, edgy narrative rhythm" of a story of persecution, satire, and Expressionist art. The story, he suggests, may be allegory of the Weimar Republic in which it arose.[4]

Notes

- French: 25 images de la passion d'un homme

- French: Mon livre d'heures

References

- Bi 2009.

- Beronä 2008, p. 93.

- Sennewald 1999, p. 138.

- Gasser 2006.

- Willett 2005, pp. 111–114.

- Walker 2007, p. 23.

- Sennewald 1999, p. 139.

- Beronä 2008, p. 248.

- Smart 2011, pp. 22–23.

- Beronä 2008, p. 245.

- Beronä 2008, p. 93; Walker 2007, p. 22.

- Spiegelman 2010, pp. 804–805.

- Ward & Beronä 2005, p. v.

- Cohen 1977, p. 191.

- Beronä 2008, p. 97.

Works cited

- Ward, Lynd; Beronä, David (2005). "Introduction". Mad Man's Drum: A Novel in Woodcuts. Dover Publications. pp. iii–vi. ISBN 978-0-486-44500-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beronä, David A. (2008). Wordless Books: The Original Graphic Novels. Abrams Books. ISBN 978-0-8109-9469-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bi, Jessie (May 2009). "Destin de Otto Nückel". du9 (in French). Archived from the original on 2014-03-15. Retrieved 2013-03-18.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cohen, Martin S. (April 1977). "The Novel in Woodcuts: A Handbook". Journal of Modern Literature. Indiana University Press. 6 (2): 171–195. JSTOR 3831165.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gasser, Christian (2006-01-26). "Stummes Elend: Der Bilder-Roman "Destin" von Otto Nückel" [Dumb Misery: The Pictures Novel "Destiny" by Otto Nückel]. Neue Zürcher Zeitung. Archived from the original on 2014-10-19. Retrieved 2014-10-10.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sennewald, Adolf (1999). Deutsche Buchillustratoren im ersten Drittel des 20. Jahrhunderts: Materialien für Bibliophile [German Book Illustrators in the First Third of the 20th Century: Materials for Bibliophiles]. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-04228-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Smart, Tom (Spring 2011). "A Suite of Engravings from The Mysterious Death of Tom Thomson". Devil's Artisan. The Porcupine's Quill. 68: 10–37.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Spiegelman, Art (2010). "Chronology". In Spiegelman, Art (ed.). Lynd Ward: God's Man, Madman's Drum, Wild Pilgrimage. Library of America. pp. 799–821. ISBN 978-1-59853-080-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Walker, George, ed. (2007). Graphic Witness: Four Wordless Graphic Novels. Firefly Books. ISBN 978-1-55407-270-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Willett, Perry (2005). "The Cutting Edge of German Expressionism: The Woodcut Novel of Frans Masereel and Its Influences". In Donahue, Neil H. (ed.). A Companion to the Literature of German Expressionism. Camden House Publishing. pp. 111–134. ISBN 978-1-57113-175-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Lehmann-Haupt, Hellmut (1930-02-01). "The Picture-Novel Arrives in America". Publishers Weekly: 609–612.

- Kronthaler, Helmut (2009). Sackmann, Eckart (ed.). "Otto Nückel und der Bilderroman ohne Worte" [Otto Nückel and the Picture-Novel without Words]. Deutsche Comicforschung 2010 (in German). Hildesheim: 65–73. ISBN 978-3-89474-199-0.