Daulatabad Fort

Daulatabad Fort, also known as Devagiri or Deogiri, is a historical fortified citadel located in Aurangabad, Maharashtra, India. It was the capital of the Yadava dynasty (9th century–14th century CE), for a brief time the capital of the Delhi Sultanate (1327–1334), and later a secondary capital of the Ahmadnagar Sultanate (1499–1636).[1][2][3][4][2][5] Around the sixth century CE, Devagiri emerged as an important uplands town near present-day Aurangabad, along caravan routes going towards western and southern India.[6][7][8][9] The historical triangular fortress in the city was initially built around 1187 by the first Yadava king, Bhillama V.[10] In 1308, the city was annexed by Sultan Alauddin Khalji of the Delhi Sultanate, which ruled over most of the Indian subcontinent. In 1327, Sultan Muhammad bin Tughluq of the Delhi Sultanate renamed the city as "Daulatabad" and shifted his imperial capital to the city from Delhi, ordering a mass migration of Delhi's population to Daulatabad. However, Muhammad bin Tughluq reversed his decision in 1334 and the capital of the Delhi Sultanate was shifted back from Daulatabad to Delhi.[11] In 1499, Daulatabad became a part of the Ahmadnagar Sultanate, who used it as their secondary capital. In 1610, near Daulatabad Fort, the new city of Aurangabad, then named Khadki, was established to serve as the capital of the Ahmadnagar Sultanate by the Ethiopian military leader Malik Ambar, who was brought to India as a slave but rose to become a popular Prime Minister of the Ahmadnagar Sultanate. Most of the present-day fortification at Daulatabad Fort was constructed under the Ahmadnagar Sultanate.

| Daulatabad Fort | |

|---|---|

Devagiri, Deogiri | |

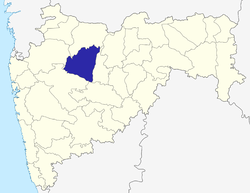

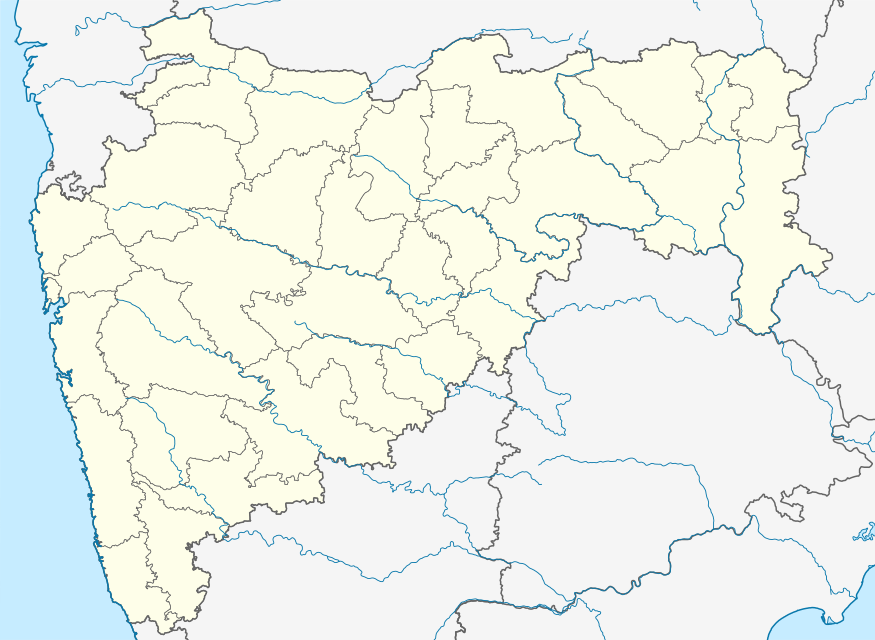

Location within Maharashtra | |

| General information | |

| Country | India |

| Coordinates | 19.942724°N 75.213164°E |

| Completed | 1600s |

Mythological origin

Lord Shiva is believed to have stayed on the hills surrounding this region. Hence the fort was originally known as Devagiri, literally "hills of god".[12][13]

The Fort

The area of the city the hill-fortress of Devagiri (sometimes Latinised to Deogiri). It stands on a conical hill, about 200 meters high. Much of the lower slopes of the hill has been cut away by Yadava dynasty rulers to leave 50-meter vertical sides to improve defenses. The fort is a place of extraordinary strength. The only means of access to the summit is by a narrow bridge, with the passage for not more than two people abreast, and a long gallery, excavated in the rock, which has, for the most part, a very gradual upward slope.[14]

About midway along this gallery, the access gallery has steep stairs, the top of which is covered by a grating destined in time of war to form the hearth of a huge fire kept burning by the garrison above.[15] At the summit, and at intervals on the slope, are specimens of massive old cannon facing out over the surrounding countryside. Also at the midway, there is a cave entrance meant to confuse the enemies.[16]

The fort had the following specialties which are listed along with their advantages :

- No separate exit from the fort, only one entrance/exit - This is designed to confuse the enemy soldiers to drive deep into the fort in search of an exit, at their own peril.

- No parallel gates - This is designed to break the momentum of the invading army. Also, the flag mast is on the left hill, which the enemy will try to capitulate, thus will always turn left. But the real gates of the fort are on the right & the false ones on the left, thus confusing the enemy.

- Spikes on the gates - In the era before gunpowder, intoxicated elephants were used as a battering ram to break open the gates. The presence of spikes ensured that the elephants died of injury.

- Complex arrangement of entryways, curved walls, false doors - Designed to confuse the enemy, false, but well-designed gates on the left side lured the enemy soldiers in & trapped them inside, eventually feeding them to crocodiles.

- The hill is shaped like a smooth tortoise back - this prevented the use of mountain lizards as climbers, because they cannot stick to it.

The City

Daulatabad (19°57’N 75°15’E) is located at a distance of 16 km northwest of Aurangabad, the district headquarters and midway to Ellora group of caves.[17] The original widespread capital city is now mostly unoccupied and has been reduced to a village. Much of its survival depends on the tourists to the old city and the adjacent fort.

History

.jpg)

The site had been occupied since at least 100 BCE, and now has remains of Hindu & Jain temples similar to those at Ajanta and Ellora.[18][19] A series of niches carved with Jain Tirthankara in cave 32.[20]

The city is said to have been founded c. 1187 by Bhillama V, a Yadava prince who renounced his allegiance to the Chalukyas and established the power of the Yadava dynasty in the west.[21] During the rule of the Yadava king Ramachandra, Alauddin Khalji of Delhi Sultanate raided Devagiri in 1296, forcing the Yadavas to pay a hefty tribute.[22] When the tribute payments stopped, Alauddin sent a second expedition to Devagiri in 1308, forcing Ramachandra to become his vassal.[23]

In 1328, Muhammad bin Tughluq of Delhi Sultanate transferred the capital of his kingdom to Devagiri, and renamed it Daulatabad. The sultan made Daulatabad (Devagiri) his second capital in 1327 [24]. Some scholars argue that the idea behind transferring the capital was rational, because it lay more or less in the centre of the kingdom, and geographically secured the capital from the north-west frontier attacks.

In the Daulatabad fort, he found the area arid & dry. Hence he built a huge reservoir for water storage & connected it with a far-away river. He used siphon system to fill up the reservoir. However, his capital-shift strategy failed miserably. Hence he shifted back to Delhi & earned him the moniker "Mad King".

The next important event in the Daulatabad fort time-line was the construction of the Chand Minar by the Bahmani ruler Hasan Gangu Bahmani, also known as Ala-ud-Din Bahman Shah (r. 3 August 1347 – 11 February 1358).

Hasan Gangu built the Chand Minar as a replica of the Qutb Minar of Delhi, of which he was a great fan of. He employed Iranian architects to built the Minar who used Lapis Lazuli & Red Ocher for coloring. Currently, the Minar is out of bounds for the tourists, because of a suicide case.

As we move further into the fort, we can see the Chini Mahal, a VIP prison built by Aurangzeb. In this prison, he kept Abul Hasan Tana Shah of the Qutb Shahi Dynasty of Hyderabad. The antecedents of Abul Hasan Tana Shah, the last Qutub Shahi king are shrouded in mystery. Although a kinsman of the Golconda royals, he spent his formative years as a disciple of renowned Sufi saint Shah Raju Qattal, leading a spartan existence away from the pomp and grandeur of royalty. Shah Raziuddin Hussaini, popularly known as Shah Raju, was held in high esteem by both the nobility and commoners of Hyderabad. Abdullah Qutub Shah, the seventh king of Golconda was among his most ardent devotees. He died in prison leaving no male heir to the throne.

Most of the present-day fortification was constructed under the Bahmanis and the Nizam Shahs of Ahmadnagar.[1] The Mughal Governor of the Deccan under Shah Jahan, captured the fortress in 1632 and imprisoned the Nizam Shahi prince Husain Shah.[25]

Monuments

The outer wall, 2.75 miles (4.43 km) in circumference, once enclosed the ancient city of Devagiri and between this and the base of the upper fort are three lines of defenses.

Along with the fortifications, Daulatabad contains several notable monuments, of which the chief are the Chand Minar and the Chini Mahal.[26] The Chand Minar is a tower 210 ft (64 m). high and 70 ft (21 m). in circumference at the base, and was originally covered with beautiful Persian glazed tiles. It was erected in 1445 by Ala-ud-din Bahmani to commemorate his capture of the fort. The Chini Mahal (literally: China Palace), is the ruin of a building once of great beauty. In it, Abul Hasan Tana Shah, the last of the Qutb Shahi kings of Golconda, was imprisoned by Aurangzeb in 1687.[21]

Transport

Road Transport

Daulatabad is in the outskirts of Aurangabad, and is on the Aurangabad - Ellora road (National Highway 2003). Aurangabad is well connected by road and 20 km away from Devagiri.[27]

Rail Transport

Daulatabad railway station is located on the Manmad-Purna section of South Central Railways[28] and also on the Mudkhed-Manmad section of the Nanded Division of South Central Railway. Until reorganisation in 2005, it was a part of the Hyderabad Division Aurangabad is a major station near Daulatabad. The Devagiri Express regularly operates between Mumbai and Secunderabad, Hyderabad, via the city of Aurangabad.

Gallery

Front view of Daulatabad fort

Front view of Daulatabad fort Chand Minar

Chand Minar.jpg) Jain relics

Jain relics.jpg) Jain Relics

Jain Relics- Daulatabad Fort

Daulatabad Fort

Daulatabad Fort Daulatabad, Aurangabad

Daulatabad, Aurangabad- Daulatabad Prison

Gateway to Daulatabad Fort

Gateway to Daulatabad Fort- Daulatabad fort entrance

- Aurangabad-Daulatabad Fort

- Dualatabad Fort

Daulatabad Fort

Daulatabad Fort- Aurangabad - Daulatabad Fort

- Aurangabad - Daulatabad Fort

- Daulatabad Fort Gate

Daulatabad Fort -Aurangabad

Daulatabad Fort -Aurangabad- Daulatabad Fort

Daulatabad Fort, Aurangabad

Daulatabad Fort, Aurangabad Daulatabad Fort

Daulatabad Fort

See also

- Tourism in Marathwada

- Tourist attractions in Aurangabad, Maharashtra

References

- Sohoni, Pushkar (2015). Aurangabad with Daulatabad, Khuldabad and Ahmadnagar. Mumbai; London: Jaico Publishing House; Deccan Heritage Foundation. ISBN 9788184957020.

- "Devagiri-Daulatabad Fort". Maharashtra Tourism Development Corporation. Maharashtra, India. Archived from the original on 2 July 2014. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- "मध्यकालीन भारत में सबसे ताकतवर था दौलताबाद किला" [Madhyakālīn Bhārat Mēṁ Sabsē Tākatavar Thā Daulatābād Kilā]. Aaj Tak (in Hindi). India. 22 August 2012. Retrieved 16 November 2018.

- "देवगिरी – दौलताबाद" [Dēvagirī - Daulatābād]. www.majhapaper.com (in Marathi). Maharashtra. 9 September 2012. Retrieved 16 November 2018.

- Gopal, Madan (1990). K.S. Gautam (ed.). India through the ages. Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 174. ASIN B003DXXMC4.

- "ऑक्टोबरपासून हॉट बलून सफारी" [Octoberpāsūn Hot Balloon Safari]. Maharashtra Times (in Marathi). Khultabad. 25 May 2015. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- Neha Madaan (22 March 2015). "Virtual walks through tourist spots may be a reality". The Times of India. Pune. Retrieved 16 November 2018.

- "રાજ્યના 'સેવન વંડર્સ'માં અજંતા, સીએસટી, દૌલતાબાદ, લોનાર" [Rājyanā 'Seven Wonders'māṁ Ajantā, Sī'ēsaṭī, Daulatābād, Lōnār]. Divya Bhaskar (in Gujarati). India. November 2013. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- "स्वरध्यास फाउंडेशनच्या कलावंतांनी स्वच्छ केला दौलताबाद किल्ला" [Svaradhyās Foundationcyā Kalāvantānnī Svacch Kēlā Daulatābād Killā]. Divya Marathi. Aurangabad. 18 November 2014. Archived from the original on 13 June 2015. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- Bajwa, Jagir Singh; Kaur, Ravinder (2007). Tourism Management. APH Publishing. p. 249. ISBN 9788131300473. Retrieved 3 July 2016.

- Raj Goswami (May 2015). "UID યુનિક ઈન્ડિયન ડોન્કી!" [UID Unique Indian Delhi]. Mumbai Samachar (in Gujarati). India. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- Vidya Shrinivas Dhoot (February 2012). "देवगिरी किल्ल्याच्या बुरुजावरून." [Dēvagirī Killyācyā Burujāvarūn..]. Divya Marathi (in Marathi). Aurangabad, Maharashtra. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- Dayanand Pingale (11 January 2014). "अद्भुत देवगिरी" [Adbhut Dēvagirī]. Prahaar (in Marathi). Aurangabad, Maharashtra. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- Gopal, Madan (1990). K.S. Gautam (ed.). India through the ages. Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 176. ASIN B003DXXMC4.

-

- "दौलतीचे शहर दौलताबाद" [Daulatīcē śahar Daulatābād]. Maharashtra Times (in Marathi). Maharashtra. December 2007. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- "Ticketed Monuments - Maharashtra Daulatabad Fort". Archaeological Survey of India. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- Jain, Shikha; Hooja, Rima (23 September 2016). Conserving Fortified Heritage: The Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Fortifications and World Heritage, New Delhi, 2015. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4438-9637-5.

- Gopal, Balakrishnan Raja (1994). The Rashtrakutas of Malkhed: Studies in the History and Culture. Mythic Society, Bangalore by Geetha Book House.

- Limited, Eicher Goodearth (2001). Speaking Stones: World Cultural Heritage Sites in India. Eicher Goodearth Limited. ISBN 978-81-87780-00-7.

- Qureshi, Dulari (2004). Fort of Daulatabad. New Delhi: Bharatiya Kala Prakashan. ISBN 978-8180901133. Retrieved 7 March 2010.

- Kishori Saran Lal (1950). History of the Khaljis (1290-1320). Allahabad: The Indian Press. pp. 55–57. OCLC 685167335.

- Banarsi Prasad Saksena (1992). "The Khaljis: Alauddin Khalji". In Mohammad Habib and Khaliq Ahmad Nizami (ed.). A Comprehensive History of India: The Delhi Sultanat (A.D. 1206-1526). 5 (Second ed.). The Indian History Congress / People's Publishing House. pp. 192–193. OCLC 31870180.

- https://www.britannica.com/place/India/The-Tughluqs

- Sen, Sailendra (2013). A Textbook of Medieval Indian History. Primus Books. p. 170. ISBN 978-9-38060-734-4.

- "अभेद्य थी दौलताबाद किले की सुरक्षा" [Abhēdya Thī Daulatābād Kilē Kī Surakṣā]. www.prabhasakshi.com (in Marathi). New Delhi. 22 May 2012. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- "Devgiri-Daultabad Fort". www.aurangabadcity.com. Aurangabad, Maharashtra. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- Hārd Samā. "ઐતિહાસિક સ્થળો" [Aitihāsik Sthaḷō]. www.gujaratcentre.com (in Gujarati). India. Retrieved May 2015. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Daulatabad Fort. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Daulatabad Fort |