Social behavior

Social behavior is behavior among two or more organisms within the same species, and encompasses any behavior in which one member affects the other. This is due to an interaction among those members.[1][2] Social behavior can be seen as similar to an exchange of goods, with the expectation that when you give, you will receive the same.[3] This behavior can be effected by both the qualities of the individual and the environmental (situational) factors. Therefore, social behavior arises as a result of an interaction between the two—the organism and its environment. This means that, in regards to humans, social behavior can be determined by both the individual characteristics of the person, and the situation they are in.[4]

A major aspect of social behavior is communication, which is the basis for survival and reproduction.[5] Social behavior is said to be determined by two different processes, that can either work together or oppose one another. The dual-systems model of reflective and impulsive determinants of social behavior came out of the realization that behavior cannot just be determined by one single factor. Instead, behavior can arise by those consciously behaving (where there is an awareness and intent), or by pure impulse. These factors that determine behavior can work in different situations and moments, and can even oppose one another. While at times one can behave with a specific goal in mind, other times they can behave without rational control, and driven by impulse instead.[6]

There are also distinctions between different types of social behavior, such as mundane versus defensive social behavior. Mundane social behavior is a result of interactions in day-to-day life, and are behaviors learned as one is exposed to those different situations. On the other hand, defensive behavior arises out of impulse, when one is faced with conflicting desires.[7]

The development of social behavior

Social behavior constantly changes as one continues to grow and develop, reaching different stages of life. The development of behavior is deeply tied with the biological and cognitive changes one is experiencing at any given time. This creates general patterns of social behavior development in humans.[8] Just as social behavior is influenced by both the situation and an individual's characteristics, the development of behavior is due to the combination of the two as well—the temperament of the child along with the settings they are exposed to.[9][7]

Culture (parents and individuals that influence socialization in children) play a large role in the development of a child's social behavior, as the parents or caregivers are typically those who decide the settings and situations that the child is exposed to. These various settings the child is placed in (for example, the playground and classroom) form habits of interaction and behavior insomuch as the child being exposed to certain settings more frequently than others. What takes particular precedence in the influence of the setting are the people that the child must interact with—their age, sex, and at times culture.[7]

Emotions also play a large role in the development of social behavior, as they are intertwined with the way an individual behaves. Through social interactions, emotion is understood through various verbal and nonverbal displays, and thus plays a large role in communication. Many of the processes that occur in the brain and underlay emotion often greatly correlate with the processes that are needed for social behavior as well. A major aspect of interaction is understanding how the other person thinks and feels, and being able to detect emotional states becomes necessary for individuals to effectively interact with one another and behave socially.[10]

As the child continues to gain social information, their behavior develops accordingly.[5] One must learn how to behave according to the interactions and people relevant to a certain setting, and therefore begin to intuitively know the appropriate form of social interaction depending on the situation. Therefore, behavior is constantly changing as required, and maturity brings this on. A child must learn to balance their own desires with those of the people they interact with, and this ability to correctly respond to contextual cues and understand the intentions and desires of another person improves with age.[7] That being said, the individual characteristics of the child (their temperament) is important to understanding how the individual learns social behaviors and cues given to them, and this learnability is not consistent across all children.[9]

Patterns of development across the lifespan

When studying patterns of biological development across the human lifespan, there are certain patterns that are well-maintained across humans. These patterns can often correspond with social development, and biological changes lead to respective changes in interactions.[8]

In pre and post-natal infancy, the behavior of the infant is correlated with that of the caregiver. In infancy, there is already a development of the awareness of a stranger, in which case the individual is able to identify and distinguish between people.[8]

Come childhood, the individual begins to attend more to their peers, and communication begins to take a verbal form. One also begins to classify themselves on the basis of their gender and other qualities salient about themselves, like race and age.[8]

When the child reaches school age, one typically becomes more aware of the structure of society in regards to gender, and how their own gender plays a role in this. They become more and more reliant on verbal forms of communication, and more likely to form groups and become aware of their own role within the group.[8]

By puberty, general relations among same and opposite sex individuals are much more salient, and individuals begin to behave according to the norms of these situations. With increasing awareness of their sex and stereotypes that go along with it, the individual begins to choose how much they align with these stereotypes, and behaves either according to those stereotypes or not. This is also the time that individuals more often form sexual pairs.[8]

Once the individual reaches childrearing age, one must begin to undergo changes within the own behavior in accordance to major life-changes of a developing family. The potential new child requires the parent to modify their behavior to accommodate a new member of the family.[8]

Come senescence and retirement, behavior is more stable as the individual has often established their social circle (whatever it may be) and is more committed to their social structure.[8]

Neural and biological correlates of social behavior

Neural correlates

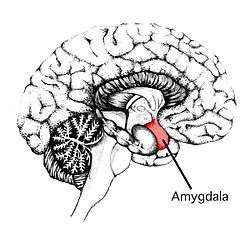

With the advent of the field social cognitive neuroscience came interest in studying social behavior's correlates within the brain, to see what is happening beneath the surface as organisms act in a social manner.[11] Although there is debate on which particular regions of the brain are responsible for social behavior, some have claimed that the paracingulate cortex is activated when one person is thinking about the motives or aims of another, a means of understanding the social world and behaving accordingly. The medial prefrontal lobe has also been seen to have activation during social cognition[12] Research has discovered through studies on rhesus monkeys that the amygdala, a region known for expressing fear, was activated specifically when the monkeys were faced with a social situation they had never been in before. This region of the brain was shown to be sensitive to the fear that comes with a novel social situation, inhibiting social interaction.[13]

Another form of studying the brain regions that may be responsible for social behavior has been through looking at patients with brain injuries who have an impairment in social behavior. Lesions in the prefrontal cortex that occurred in adulthood can effect the functioning of social behavior. When these lesions or a dysfunction in the prefrontal cortex occur in infancy/early on in life, the development of proper moral and social behavior is effected and thus atypical.[14]

Biological correlates

Along with neural correlates, research has investigated what happens within the body (and potentially modulates) social behavior. Vasopressin is a posterior pituitary hormone that is seen to potentially play a role in affiliation for young rats. Along with young rats, vasopressin has also been associated with paternal behavior in prairie voles. Efforts have been made to connect animal research to humans, and found that vasopressin may play a role in the social responses of males in human research.[15]

Oxytocin has also been seen to be correlated with positive social behavior, and elevated levels have been shown to potentially help improve social behavior that may have been suppressed due to stress. Thus, targeting levels of oxytocin may play a role in interventions of disorders that deal with atypical social behavior.[16]

Along with vasopressin, serotonin has also been inspected in relation to social behavior in humans. It was found to be associated with human feelings of social connection, and we see a drop in serotonin when one is socially isolated or has feelings of social isolation. Serotonin has also been associated with social confidence.[15]

Affect and social behavior

Positive affect (emotion) has been seen to have a large impact on social behavior, particularly by inducing more helping behavior, cooperation, and sociability.[17] Studies have shown that even subtly inducing positive affect within individuals caused greater social behavior and helping. This phenomenon, however, is not one-directional. Just as positive affect can influence social behavior, social behavior can have an influence on positive affect.[18]

Electronic media and social behavior

Social behavior has typically been seen as a changing of behaviors relevant to the situation at hand, acting appropriately with the setting one is in. However, with the advent of electronic media, people began to find themselves in situations they may have not been exposed to in everyday life. Novel situations and information presented through electronic media has formed interactions that are completely new to people. While people typically behaved in line with their setting in face-to-face interaction, the lines have become blurred when it comes to electronic media. This has led to a cascade of results, as gender norms started to merge, and people were coming in contact with information they had never been exposed to through face-to-face interaction. A political leader could no longer tailor a speech to just one audience, for their speech would be translated and heard by anyone through the media. People can no longer play drastically different roles when put in different situations, because the situations overlap more as information is more readily available. Communication flows more quickly and fluidly through media, causing behavior to merge accordingly.[19]

.jpg)

Media has also been shown to have an impact on promoting different types of social behavior, such as prosocial and aggressive behavior. For example, violence shown through the media has been seen to lead to more aggressive behavior in its viewers.[20][21] Research has also been done investigating how media portraying positive social acts, prosocial behavior, could lead to more helping behavior in its viewers. The general learning model was established to study how this process of translating media into behavior works, and why.[22][23] This model suggests a link between positive media with prosocial behavior and violent media with aggressive behavior, and posits that this is mediated by the characteristics of the individual watching along with the situation they are in. This model also presents the notion that when one is exposed to the same type of media for long periods of time, this could even lead to changes within their personality traits, as they are forming different sets of knowledge and may be behaving accordingly.[24]

In various studies looking specifically at how video games with prosocial content effect behavior, it was shown that exposure influenced subsequent helping behavior in the video-game player.[23] The processes that underlay this effect point to prosocial thoughts being more readily available after playing a video game related to this, and thus the person playing the game is more likely to behave accordingly.[25][26] These effects were not only found with video games, but also with music, as people listening to songs involving aggression and violence in the lyrics were more likely to act in an aggressive manner.[27] Likewise, people listening to songs related to prosocial acts (relative to a song with neutral lyrics) were shown to express greater helping behaviors and more empathy afterwards.[28][29] When these songs were played at restaurants, it even led to an increase in tips given (relative to those who heard neutral lyrics).[30][24]

Aggressive and violent behavior

See article: Aggression

Aggression is an important social behavior that can have both negative consequences (in a social interaction) and adaptive consequences (adaptive in humans and other primates for survival). There are many differences in aggressive behavior, and a lot of these differences are sex-difference based.[31]

Verbal, coverbal, and nonverbal social behavior

Verbal and coverbal behaviors

See articles: Conversation and Language

.jpg)

Although most animals can communicate nonverbally, humans have the ability to communicate with both verbal and nonverbal behavior. Verbal behavior is the content one's spoken word.[32] Verbal and nonverbal behavior intersect in what is known as coverbal behavior, which is nonverbal behavior that contribute to the meaning of verbal speech (i.e. hand gestures used to emphasize the importance of what someone is saying).[33] Although the spoken words convey meaning in and of themselves, one cannot dismiss the coverbal behaviors that accompany the words, as they place great emphasis on the thought and importance contributing to the verbal speech.[34][33] Therefore, the verbal behaviors and gestures that accompany it work together to make up a conversation.[34] Although many have posited this idea that nonverbal behavior accompanying speech serves an important role in communication, it is important to note that not all researchers agree.[35][33] However, in most literature on gestures, we see that unlike body language, gestures can accompany speech in ways that bring inner thoughts to life (often thoughts unable to be expressed verbally).[36] Gestures (coverbal behaviors) and speech occur simultaneously, and develop along the same trajectory within children as well.[36]

Nonverbal behaviors

See main article: Nonverbal communication

Behaviors that include any change in facial expression or body movement constitute the meaning of nonverbal behavior.[37][38] Communicative nonverbal behavior include facial and body expressions that are intentionally meant to convey a message to those who are meant to receive it.[38] Nonverbal behavior can serve a specific purpose (i.e. to convey a message), or can be more of an impulse/reflex.[38] Paul Ekman, an influential psychologist, investigated both verbal and nonverbal behavior (and their role in communication) a great deal, emphasizing how difficult it is to empirically test such behaviors.[32] Nonverbal cues can serve the function of conveying a message, thought, or emotion both to the person viewing the behavior and the person sending these cues.[39]

Disorders involving impairments in social behavior

A number of forms of mental disorder affect social behavior. Social anxiety disorder is a phobic disorder characterized by a fear of being judged by others, which manifests itself as a fear of people in general. Due to this pervasive fear of embarrassing oneself in front of others, it causes those affected to avoid interactions with other people.[40] Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder is a neurodevelopmental disorder mainly identified by its symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity. Hyperactivity-Impulsivity may lead to hampered social interactions, as one who displays these symptoms may be socially intrusive, unable to maintain personal space, and talk over others.[41] The majority of children that display symptoms of ADHD also have problems with their social behavior.[42][43] Autism Spectrum Disorder is a neurodevelopmental disorder that affects the functioning of social interaction and communication. People who fall on the autism spectrum scale may have difficulties in understanding social cues and the emotional states of others.[44]

Learning disabilities are often defined as a specific deficit in academic achievement; however, research has shown that with a learning disability can come social skill deficits as well.[45]

See also

References

- Elsevier. "The Laboratory Rat – 2nd Edition". www.elsevier.com. Retrieved 2018-11-18.

- Elsevier. "Handbook of Biologically Active Peptides – 2nd Edition". www.elsevier.com. Retrieved 2018-11-18.

- Homans, George C. (1958). "Social Behavior as Exchange". American Journal of Sociology. 63 (6): 597–606. doi:10.1086/222355. JSTOR 2772990.

- Snyder, Mark; Ickes, W. (1985). "Personality and social behavior". Handbook of Social Psychology: 883–948.

- Robinson, Gene E.; Fernald, Russell D.; Clayton, David F. (2008-11-07). "Genes and Social Behavior". Science. 322 (5903): 896–900. Bibcode:2008Sci...322..896R. doi:10.1126/science.1159277. ISSN 0036-8075. PMC 3052688. PMID 18988841.

- Strack, Fritz; Deutsch, Roland (2004). "Reflective and impulsive determinants of social behavior". Personality and Social Psychology Review. 8 (3): 220–247. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.323.2327. doi:10.1207/s15327957pspr0803_1. ISSN 1088-8683. PMID 15454347.

- Whiting, Beatrice Blyth (1980). "Culture and Social Behavior: A Model for the Development of Social Behavior". Ethos. 8 (2): 95–116. doi:10.1525/eth.1980.8.2.02a00010. JSTOR 640018.

- Elsevier. "Children's Social Behavior – 1st Edition". www.elsevier.com. Retrieved 2018-11-18.

- Rothbart, Mary K.; Ahadi, Stephan A.; Hershey, Karen L. (1994). "Temperament and Social Behavior in Childhood". Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 40 (1): 21–39. JSTOR 23087906.

- Elsevier. "Advances in Child Development and Behavior, Volume 36 – 1st Edition". www.elsevier.com. Retrieved 2018-11-19.

- Behrens, Timothy E. J.; Hunt, Laurence T.; Rushworth, Matthew F. S. (2009-05-29). "The Computation of Social Behavior". Science. 324 (5931): 1160–1164. Bibcode:2009Sci...324.1160B. doi:10.1126/science.1169694. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 19478175.

- Amodio, David M.; Frith, Chris D. (April 2006). "Meeting of minds: the medial frontal cortex and social cognition". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 7 (4): 268–277. doi:10.1038/nrn1884. ISSN 1471-003X. PMID 16552413.

- Amaral, David G. (December 2003). "The amygdala, social behavior, and danger detection". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1000 (1): 337–347. Bibcode:2003NYASA1000..337A. doi:10.1196/annals.1280.015. ISSN 0077-8923. PMID 14766647.

- Anderson, Steven W.; Bechara, Antoine; Damasio, Hanna; Tranel, Daniel; Damasio, Antonio R. (November 1999). "Impairment of social and moral behavior related to early damage in human prefrontal cortex". Nature Neuroscience. 2 (11): 1032–1037. doi:10.1038/14833. ISSN 1097-6256. PMID 10526345.

- Snyder, C. R.; Lopez, Shane J. (2002). Handbook of Positive Psychology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195135336.

- Rotzinger, Susan (2013-01-01). "Peptides and Behavior". Handbook of Biologically Active Peptides. pp. 1858–1863. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-385095-9.00254-2. ISBN 9780123850959.

- Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Academic Press. 1987-11-05. ISBN 9780080567341.

- Isen, Alice M.; Levin, Paula F. (1972). "Effect of feeling good on helping: Cookies and kindness". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 21 (3): 384–388. doi:10.1037/h0032317. ISSN 1939-1315. PMID 5060754.

- Meyrowitz, Joshua (1986-12-11). No Sense of Place: The Impact of Electronic Media on Social Behavior. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198020578.

- Anderson, Craig A.; Shibuya, Akiko; Ihori, Nobuko; Swing, Edward L.; Bushman, Brad J.; Sakamoto, Akira; Rothstein, Hannah R.; Saleem, Muniba (2010). "Violent video game effects on aggression, empathy, and prosocial behavior in Eastern and Western countries: A meta-analytic review". Psychological Bulletin. 136 (2): 151–173. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.535.382. doi:10.1037/a0018251. ISSN 1939-1455. PMID 20192553.

- Bushman, Brad J.; Huesmann, L. Rowell (2006-04-01). "Short-term and Long-term Effects of Violent Media on Aggression in Children and Adults" (PDF). Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 160 (4): 348–52. doi:10.1001/archpedi.160.4.348. ISSN 1072-4710. PMID 16585478.

- Vorderer, Peter (2012-10-12). Playing Video Games. doi:10.4324/9780203873700. ISBN 9780203873700.

- Gentile, Douglas A.; Anderson, Craig A.; Yukawa, Shintaro; Ihori, Nobuko; Saleem, Muniba; Lim Kam Ming; Shibuya, Akiko; Liau, Albert K.; Khoo, Angeline (2009-03-25). "The Effects of Prosocial Video Games on Prosocial Behaviors: International Evidence From Correlational, Longitudinal, and Experimental Studies". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 35 (6): 752–763. doi:10.1177/0146167209333045. ISSN 0146-1672. PMC 2678173. PMID 19321812.

- Greitemeyer, Tobias (August 2011). "Effects of Prosocial Media on Social Behavior". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 20 (4): 251–255. doi:10.1177/0963721411415229. ISSN 0963-7214.

- Greitemeyer, Tobias; Osswald, Silvia (2010). "Effects of prosocial video games on prosocial behavior". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 98 (2): 211–221. doi:10.1037/a0016997. ISSN 1939-1315. PMID 20085396.

- Greitemeyer, Tobias; Osswald, Silvia (2011-02-17). "Playing Prosocial Video Games Increases the Accessibility of Prosocial Thoughts". The Journal of Social Psychology. 151 (2): 121–128. doi:10.1080/00224540903365588. ISSN 0022-4545. PMID 21476457.

- Fischer, Peter; Greitemeyer, Tobias (September 2006). "Music and Aggression: The Impact of Sexual-Aggressive Song Lyrics on Aggression-Related Thoughts, Emotions, and Behavior Toward the Same and the Opposite Sex". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 32 (9): 1165–1176. doi:10.1177/0146167206288670. ISSN 0146-1672. PMID 16902237.

- Greitemeyer, Tobias (January 2009). "Effects of songs with prosocial lyrics on prosocial thoughts, affect, and behavior". Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 45 (1): 186–190. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2008.08.003. ISSN 0022-1031.

- Greitemeyer, Tobias (2009-07-31). "Effects of Songs With Prosocial Lyrics on Prosocial Behavior: Further Evidence and a Mediating Mechanism". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 35 (11): 1500–1511. doi:10.1177/0146167209341648. ISSN 0146-1672. PMID 19648562.

- Jacob, Céline; Guéguen, Nicolas; Boulbry, Gaëlle (December 2010). "Effects of songs with prosocial lyrics on tipping behavior in a restaurant". International Journal of Hospitality Management. 29 (4): 761–763. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2010.02.004. ISSN 0278-4319.

- De Almeida, Rosa Maria Martins; Cabral, João Carlos Centurion; Narvaes, Rodrigo (2015-05-01). "Behavioural, hormonal and neurobiological mechanisms of aggressive behaviour in human and nonhuman primates". Physiology & Behavior. 143: 121–135. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2015.02.053. ISSN 0031-9384. PMID 25749197.

- Ekman, Paul (January 1957). "A Methodological Discussion of Nonverbal Behavior". The Journal of Psychology. 43 (1): 141–149. doi:10.1080/00223980.1957.9713059. ISSN 0022-3980.

- Miller, E. (2010-06-30). Fiske, Susan T.; Gilbert, Daniel T.; Lindzey, Gardner (eds.). Handbook of Social Psychology. Mental Health. 6. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 86. doi:10.1002/9780470561119. ISBN 9780470561119. PMC 5092955.

- Kendon, Adam; Harris, Richard M.; Key, Mary Ritchie (1975). Organization of Behavior in Face-to-face Interaction. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 9789027975690.

- Krauss, Robert M.; Chen, Yihsiu; Gottesman, Rebecca F. (2000), Language and Gesture, Cambridge University Press, pp. 261–283, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.486.6399, doi:10.1017/cbo9780511620850.017, ISBN 9780511620850

- McNeill, David (1992-08-15). Hand and Mind: What Gestures Reveal about Thought. University of Chicago Press. p. 6. ISBN 9780226561325.

emblem gestures.

- Krauss, Robert M.; Chen, Yihsiu; Chawla, Purnima (1996), "Nonverbal Behavior and Nonverbal Communication: What do Conversational Hand Gestures Tell Us?", Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Elsevier, pp. 389–450, doi:10.1016/s0065-2601(08)60241-5, ISBN 9780120152285

- Ekman, Paul; Friesen, Wallace V. (1981), Nonverbal Communication, Interaction, and Gesture, DE GRUYTER MOUTON, doi:10.1515/9783110880021.57, ISBN 9783110880021

- author., Knapp, Mark L. (2013-01-01). Nonverbal communication in human interaction. ISBN 9781133311591. OCLC 800033348.

- Stein, Murray B.; Stein, Dan J. (2008-03-29). "Social anxiety disorder". The Lancet. 371 (9618): 1115–1125. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60488-2. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 18374843.

- "NIMH " Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder". www.nimh.nih.gov. Retrieved 2018-11-21.

- Huang-Pollock, Cynthia L.; Mikami, Amori Yee; Pfiffner, Linda; McBurnett, Keith (July 2009). "Can executive functions explain the relationship between Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and social adjustment?". Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 37 (5): 679–691. doi:10.1007/s10802-009-9302-8. ISSN 1573-2835. PMID 19184400.

- Kofler, Michael J.; Rapport, Mark D.; Bolden, Jennifer; Sarver, Dustin E.; Raiker, Joseph S.; Alderson, R. Matt (2011-04-06). "Working Memory Deficits and Social Problems in Children with ADHD". Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 39 (6): 805–817. doi:10.1007/s10802-011-9492-8. ISSN 0091-0627. PMID 21468668.

- "WHO | ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders". www.who.int. Retrieved 2018-11-20.

- Kavale, Kenneth A.; Forness, Steven R. (May 1996). "Social Skill Deficits and Learning Disabilities: A Meta-Analysis". Journal of Learning Disabilities. 29 (3): 226–237. doi:10.1177/002221949602900301. ISSN 0022-2194. PMID 8732884.