Decad (Sumerian texts)

The Decad is a name given to a standard sequence of ten scribal training compositions in ancient Sumer.[1]

| Part of a series on |

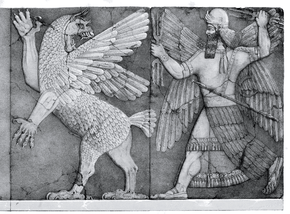

| Ancient Mesopotamian religion |

|---|

Chaos Monster and Sun God |

|

Seven gods who decree

|

|

Other major deities |

|

Demigods and heroes

|

| Related topics |

Sources and evidence

The grouping of compositions known as the Decad is attested in several literary catalogues of tablets dating to Mesopotamia's Old Babylonian period. Sumerian literary catalogues were lists of literary compositions recorded by their initial lines or incipits. While literary catalogues were normally used for administration of a library,[2] the Decad is argued to have been written on curricular tablets. The best attestation of the Decad is on a tablet originating in ancient Nippur and now stored at the University Museum in Philadelphia (referred to in this article as P). This tablet lists sixty-two Sumerian literary compositions in all (fifty-five of which have been identified and translated.[1]), organized into six groups of about ten entries each. The first group of ten compositions comprises the Decad. Another curricular list (L), of unknown origin and currently housed at the Louvre, appears to begin with the same sequence of ten incipits (although some parts are illegible). A third source (U) exists which is slightly adapted from (P) and (L). Whilst the first ten compositions listed are the same, or nearly the same, in each case, the extended lists differ in some places—suggesting that once scribes had completed set core works they continued their studies in a less rigid order.[3] Steve Tinney commented "the Decad constituted a required program of literary learning, used almost without exception throughout Babylonia. The Decad thus included almost all literary types available in Sumerian."[3][4]

Although the interpretation of the Decad as a standard sequence of training compositions within the Old Babylonian school curriculum is generally accepted by most scholars, the significance of these compositions' being grouped together in catalogues has been disputed. Paul Delnero, for example, has argued that there is no real evidence for distinguishing catalogues (P) and (L) from other, archival catalogues and ascribing to them a curricular function: (P) and (L) share many specific features and grouping devices with archival catalogues; their respective orderings of compositions after the first ten differ widely; and they omit several important Sumerian literary texts that one would expect to find in a school curriculum. Furthermore, compositions belonging to the Decad are listed in different positions in other catalogues. Thus it is possible that the Decad catalogues had an archival rather than a curricular function.[5]

The Tetrad

Steve Tinney also identified another group of compositions of an even more basic introductory level, which he called the Tetrad. This consisted of four brief hymns that would have introduced students to various aspects of Sumerian grammar; it was only occasionally used by some teachers. The Tetrad includes a Hymn to king Lipit-Estar of Isin (Lipit-Eshtar B), Iddin Dagan B, Enlil Bani A and Nisaba A. Tinney noted that these hymns were often found together as a collection, occasionally on a single tablet or prism.[3] Herman Vanstiphout suggested that these were "easier pieces" or "teaching texts" as they did not feature in the larger catalogues. He noted that the debates did not feature in either as they were more complex in form.[6]

Contents of the Decad

The Decad is shown below.

| Number | Title | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hymn to Shulgi (Shulgi A) | Royal hymn |

| 2 | Lipit-Estar A | Royal hymn |

| 3 | Song of the hoe | Composition around the sign AL = "hoe" |

| 4 | Inana B | Hymn to Inana or Ninmesara |

| 5 | Hymn to Enlil (Enlil A) | Hymn to Enlil or Enlilsurase |

| 6 | Kesh Temple Hymn | Temple hymn |

| 7 | Enki's Journey to Nippur | Narrative composition |

| 8 | Inana and Ebih | Narrative composition |

| 9 | Nungal A | Hymn to 'lady prison' |

| 10 | Gilgamesh and Huwawa | Narrative composition |

See also

- Eduba - Sumerian scribal school

References

- Jeremy A. Black; Jeremy Black; Graham Cunningham; Eleanor Robson (13 April 2006). The Literature of Ancient Sumer. Oxford University Press. pp. 301–. ISBN 978-0-19-929633-0. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- Samuel Noah Kramer (1942). The oldest literary catalogue: a Sumerian list of literary compositions compiled about 2000 B.C. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- Niek Veldhuis (2004). Religion, literature, and scholarship: the Sumerian composition Nanše and the birds, with a catalogue of Sumerian bird names. BRILL. pp. 63–. ISBN 978-90-04-13950-3. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- Tinney, Steve., On the Curricular Setting of Sumerian Literature, Iraq 61: 159-172. Forthcoming Elementary Sumerian Literary Texts. MC.

- Delnero, Paul. 2010. Sumerian Literary Catalogues and the Scribal Curriculum, Zeitschrift für Assyriologie 100: 32-55.

- G. J. Dorleijn; Herman L. J. Vanstiphout (1 September 2003). Cultural repertoires: structure, function, and dynamics. Peeters Publishers. pp. 15–. ISBN 978-90-429-1299-1. Retrieved 6 June 2011.