Davenport City Hall

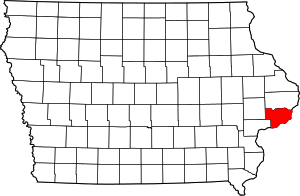

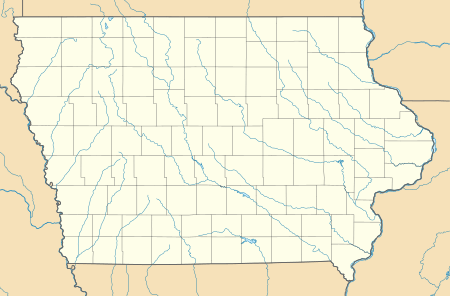

Davenport City Hall is the official seat of government for the city of Davenport, Iowa, United States. The building was constructed in 1895 and is situated on the northeast corner of the intersection of Harrison Street (U.S. Route 61) and West Fourth Street in Downtown Davenport. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1982 and on the Davenport Register of Historic Properties in 1993.

Davenport City Hall | |

Davenport built a new City Hall in 1895 for $90,000, without issuing any bonds. | |

| |

| Location | 226 W. 4th St. Davenport, Iowa |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 41°31′27″N 90°34′35″W |

| Area | less than one acre |

| Built | 1895 |

| Architect | John W. Ross |

| Architectural style | Richardsonian Romanesque |

| NRHP reference No. | 82002639[1] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | April 22, 1982 |

| Designated DRHP | June 2, 1993[2] |

History

Davenport started to outgrow its previous city hall, which had been built on Brady Street from 1857-1858.[3] The role of city government expanded during the mayoral administration of Henry Vollmer (1893-1896).[4] Among his major achievements were several public works projects. Streets were paved in the older sections of the city and developers laid out new subdivisions around the perimeter.

In 1895, in the midst of a deep national economic depression, Davenport built an ornate new City Hall. The cost was about $90,000 — an astronomical sum at that time — and the City constructed the new building without issuing any municipal bonds.[5] Local legend has long suggested that the city retired the debt so quickly by taxing the city's brothels, but the fines levied against the brothels accounted for only between $7,000-$9,000 per year, just a portion of the financial windfall the city reaped in the mid-1890s. The bulk of the funds came from a new state law (the "mulct tax") which applied to the city's 150 illegal saloons and amounted to around $50,000 per year. This tax allowed for construction not only of City Hall, but also paved streets and a new sewer system, and from 1902–08, the city eliminated its property taxes altogether.[5]

Besides Vollmer there were two other noteworthy Davenport mayors associated with this city hall. Alfred C. Mueller served the city during two separate periods (1910-1916, 1922–24). He was responsible for initiating the city's building code, sewer planning and construction, street paving, and planning and implementing improvements to the riverfront. Dr. C.L. Barewald (1920-1922) was the city's first Socialist mayor.[6] Davenport's German community had become a political force by the early 20th century and they had become disenchanted with the Democratic Party's war stance that lead the country into World War I and the anti-German sentiments that resulted. They were also opposed to the Republican Party's support for national prohibition of alcohol so they threw their support behind the Socialist Party of America. Two years prior to Barewald's election as mayor two Socialists were elected as aldermen and they were reelected in 1920. During his term as mayor, Barewald began several public works projects that put people to work and enhanced city improvements. The municipal natatorium was built, new streets were opened and a major sewer was completed. Barewald and the other two Socialists were overwhelmingly voted out of office in 1922 because of the debts these projects and others incurred.

The prohibition of alcohol was a major issue in the city of Davenport from the 1840s until national prohibition became official in 1919. The activities of the local temperance movement thrived in the 1880s and were renewed during the Progressive Era, especially between 1906 and 1916. Local ordinances were passed that exempted the city of Davenport from state prohibition laws and mayors, especially Ernst Claussen, stated that the citizen's personal liberties would not be violated.[7] Debates were held in the city council and among other civic groups until Iowa's prohibition amendment was passed in 1916. It was reinforced by the passage of the Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution in 1919. However, the illegal production and consumption of alcohol continued in the city.[6]

Architecture

City hall was designed by Davenport architect John W. Ross,[8] and built by Morrison Bros. Construction Company. The 60-by-145-foot (18 by 44 m), four-story building is constructed of Ohio Berea sandstone in the Richardsonian Romanesque style.[6] It is capped by a hipped roof. The heavy stone appearance is deceptive as the weight of the building is born by a steel frame.[3] As is common with this style, the city hall integrates corner towers, gable ends, rustic stone, and Roman arches. Three stories of windows line the front of the building. The corner tower on the west side features a cone-shaped roof and the east tower a pyramid-shaped roof. Both tower roofs rise above the main roof. Above the entrance is a large clock tower that is taller than the rest of the building. An addition was constructed on the north side in 1963 and does not correlate to the original architecture. A $2.6 million renovation of the building was completed between 1979 and 1980 and as a result the interior was reconfigured in such a way that it no longer resembles the structure's original interior.[6] In 2012 a concrete and brick building was torn down to the north of city hall and an $818,316 renovation of the 1963 addition provided a new entrance and sandstone walls that match the original 1895 building. It also added environmentally friendly features that include bioswales for stormwater and an electric car-charging station.[9]

References

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- Historic Preservation Commission. "Davenport Register of Historic Properties" (PDF). City of Davenport. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-02-11. Retrieved 2017-02-10.

- Svendsen, Marlys A.; Bowers, Martha H (1982). Davenport where the Mississippi runs west: A Survey of Davenport History & Architecture. Davenport, Iowa: City of Davenport. pp. 10–3.

- Svendsen and Bowers, 7-3

- Wood, Sharon E. (2005). The Freedom of the Streets: Work, Citizenship and Sexuality in a Gilded Age City. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 181–2. ISBN 0-8078-2939-0.

- Marlys A. Svendsen. "Davenport City Hall". National Park Service. Retrieved 2015-05-13. with photos

- "State of Scott Celebrations". Davenport Public Library. Retrieved 2015-05-13.

- Iowa Department of Cultural Affairs - State Historical Society of Iowa. "Davenport City Hall" (PDF). Davenport Public Library. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-05-18. Retrieved 2009-12-12.

- Kurt Allemeier (August 3, 2012). "Davenport City Hall receives eco-friendly facelift". Quad-City Times. Davenport. Retrieved 2015-05-13.

External links

![]()