Daishō

The daishō (大小, daishō)—literally "big-little"[1]—is a Japanese term for a matched pair of traditionally made Japanese swords (nihonto) worn by the samurai class in feudal Japan.

Description

The etymology of the word daishō becomes apparent when the terms daitō, meaning long sword, and shōtō, meaning short sword, are used; daitō + shōtō = daishō.[2] A daishō is typically depicted as a katana and wakizashi (or a tantō) mounted in matching koshirae, but originally the daishō was the wearing of any long and short uchigatana together.[3] The katana/wakizashi pairing is not the only daishō combination as generally any longer sword paired with a tantō is considered to be a daishō. Daishō eventually came to mean two swords having a matched set of fittings. A daishō could also have matching blades made by the same swordsmith, but this was in fact uncommon and not necessary for two swords to be considered to be a daishō, as it would have been more expensive for a samurai.[4][5][6][7]

History

The concept of the daisho originated with the pairing of a short sword with whatever long sword was being worn during a particular time period. The tachi would be paired with a tantō, and later the uchigatana would be paired with another shorter uchigatana. With the advent of the katana, the wakizashi eventually was chosen by samurai as the short sword over the tantō. Kanzan Satō, in his book titled The Japanese Sword, notes that there did not seem to be any particular need for the wakizashi and suggests that the wakizashi may have become more popular than the tantō as the wakizashi was more suited for indoor fighting. He mentions the custom of leaving the katana at the door of a castle or palace when entering while continuing to wear the wakizashi inside.[8]

Daishō may have become popular around the end of the Muromachi period (1336 to 1573)[9] as several early examples date from the late 16th century.[10] Wearing daishō was limited to the samurai class after the sword hunt of Toyotomi Hideyoshi in 1588, and became a symbol of their rank.[11] An edict in 1629 defining the duties of a samurai required that daishō be worn when on official duty.[12]

According to most traditional kenjutsu schools, only one sword of the daisho would have been used in combat. However, in the first half of the 17th century, the famous swordsman Miyamoto Musashi promoted the use of a one-handed grip, which allowed both swords to be used simultaneously. This technique, called nitōken, is a main element of the Niten Ichi-ryū style of swordsmanship that Musashi founded.[13]

During the Meiji period an edict was passed in 1871 abolishing the requirement that daishō be worn by samurai, and in 1876 wearing swords in public by most of Japan's population was banned; thus ended the use of the daishō as the symbol of the samurai. The samurai class was abolished soon after the sword ban.[14][15][16]

Gallery

Daisho kashira (pommel)

Daisho kashira (pommel) Daisho habaki (wedge-shaped collar)

Daisho habaki (wedge-shaped collar) Daisho tsuba and fuchi (hand guard and hilt collar)

Daisho tsuba and fuchi (hand guard and hilt collar) Daisho tsuka (hilt)

Daisho tsuka (hilt) A 19th century samurai wearing his daisho

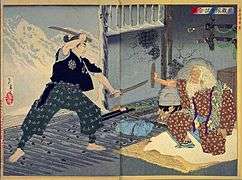

A 19th century samurai wearing his daisho A print depicting the fictional encounter between swordsmen Miyamoto Musashi and Tsukahara Bokuden, the former using both swords in the Niten Ichi-ryū style.

A print depicting the fictional encounter between swordsmen Miyamoto Musashi and Tsukahara Bokuden, the former using both swords in the Niten Ichi-ryū style.

See also

References

- The Japanese sword, Kanzan Satō, Kodansha International, 1983 p.68

- The connoisseur's book of Japanese swords, Kōkan Nagayama, Kodansha International, 1998 p.62

- The Japanese sword, Kanzan Satō, Kodansha International, 1983

- Samurai: The Weapons and Spirit of the Japanese Warrior, Clive Sinclaire, Globe Pequot, 2004 p.53

- Classical weaponry of Japan: special weapons and tactics of the martial arts, Serge Mol, Kodansha International, 2003 p.18

- The Japanese sword, Kanzan Satō, Kodansha International, 1983 – Antiques & Collectibles – 210P.68

- Katana: The Samurai Sword: 950–1877, Stephen Turnbull, Osprey Publishing, 2010 P.20

- The Japanese sword, Kanzan Satō, Kodansha International, 1983 P.68

- Samurai: The Weapons and Spirit of the Japanese Warrior, Clive Sinclaire, Globe Pequot, 2004 p.53

- The Japanese sword, Kanzan Satō, Kodansha International, 1983 p.68 & p.84

- Samurai: The Weapons and Spirit of the Japanese Warrior, Clive Sinclaire, Globe Pequot, 2004 p.53

- Cutting Edge: Japanese Swords in the British Museum, Victor Harris, Tuttle Pub., 2005 p.26

- Serge Mol, 2003, Classical Weaponry of Japan: Special Weapons and Tactics of the Martial Arts Kodansha International Ltd, ISBN 4-7700-2941-1 (pp. 22–23)

- Samurai: The Weapons and Spirit of the Japanese Warrior, Clive Sinclaire, Globe Pequot, 2004 p.58

- New directions in the study of Meiji Japan, Helen Hardacre, Adam L. Kern, BRILL, 1997 p.418

- Katana: The Samurai Sword: 950–1877, Stephen Turnbull, Osprey Publishing, 2010 P.28

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Daisho. |