3M

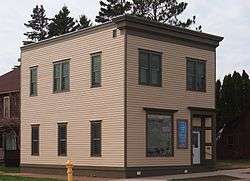

The 3M Company is an American multinational conglomerate corporation operating in the fields of industry, worker safety, US health care, and consumer goods.[4] The company produces over 60,000 products under several brands,[5] including adhesives, abrasives, laminates, passive fire protection, personal protective equipment, window films, paint protection films, dental and orthodontic products, electrical and electronic connecting and insulating materials, medical products, car-care products,[6] electronic circuits, healthcare software and optical films.[7] It is based in Maplewood, a suburb of Saint Paul, Minnesota.[8]

| |

3M headquarters in Maplewood, Minnesota | |

Formerly | Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Company (1902–2002) |

|---|---|

| Public | |

| Traded as |

|

| ISIN | US88579Y1010 |

| Industry | Conglomerate |

| Founded | June 13, 1902 (as Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Company) Two Harbors, Minnesota, U.S.[1] |

| Founders | John Dwan Hermon Cable Henry Bryan William A. McGonagle |

| Headquarters | , U.S. |

Area served | Worldwide |

Key people | Mike Roman (Chairman, President, & CEO) |

| Revenue | |

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

Number of employees | 93,516 (2018)[3] |

| Website | www |

3M made $32.8 billion in total sales in 2018, and ranked number 95 in the Fortune 500 list of the largest United States corporations by total revenue.[9] As of 2018, the company had approximately 93,500 employees, and had operations in more than 70 countries.[2]

In 2016, a complaint was filed against 3M for knowingly selling defective earplugs issued to military personnel deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan. These earplugs may have caused permanent hearing damage. 3M paid a $9.1 million settlement to the U.S. government.

History

Five businessmen founded the Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Company as a mining venture in Two Harbors, Minnesota, making their first sale on June 13, 1902.[1][10] The goal was to mine corundum, but this failed because the mine's mineral holdings were anorthosite, which had no commercial value.[10] Co-founder John Dwan solicited funds in exchange for stock and Edgar Ober and Lucius Ordway took over the company in 1905.[10] The company moved to Duluth and began researching and producing sandpaper products.[10] William L. McKnight, later a key executive, joined the company in 1907, and A. G. Bush joined in 1909.[10] 3M finally became financially stable in 1916 and was able to pay dividends.[10]

The company moved to St. Paul in 1910, where it remained for 52 years before outgrowing the campus and moving to its current headquarters at 3M Center in Maplewood, Minnesota in 1962.[11]

Expansion and modern history

In 1947, 3M began producing perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) by electrochemical fluorination.[12]

In 1951, DuPont started purchasing PFOA from then-Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Company for use in the manufacturing of teflon, a product that brought DuPont a billion-dollar-a-year profit by the 1990s.[13] DuPont referred to PFOA as C8.[14] The original formula for Scotchgard, a water repellent applied to fabrics, was discovered accidentally in 1952 by 3M chemists Patsy Sherman and Samuel Smith. Sales began in 1956, and in 1973 the two chemists received a patent for the formula.[15][16]

In the late 1950s, 3M produced the first asthma inhaler,[17] but the company did not enter the pharmaceutical industry per se until the mid-1960s with the acquisition of Riker Laboratories, moving it from California to Minnesota.[18] 3M retained the name Riker Laboratories for the subsidiary until at least 1985.[19] In the mid-1990s, 3M Pharmaceuticals, as the division came to be called, produced the first CFC-free asthma inhaler in response to adoption of the Montreal Protocol by the United States.[20][21] In the 1980s and 1990s, the company spent fifteen years developing a topical cream delivery technology which led in 1997 to health authority approval and marketing of a symptomatic treatment for genital herpes, Aldara.[22][23] After four decades, 3M divested its pharmaceutical unit through three deals in 2006, netting more than US$2 billion.[24][25] At the time, 3M Pharmaceuticals comprised about twenty percent of 3M's health care business and employed just over a thousand people.[24]

3M Mincom was involved in some of the first digital audio recordings of the late 1970s to see commercial release when a prototype machine was brought to the Sound 80 studios in Minneapolis. After drawing on the experience of that prototype recorder, 3M later introduced in 1979 a commercially available digital audio recording system called the "3M Digital Audio Mastering System",[26]

3M launched "Press 'n Peel" in stores in four cities in 1977, but results were disappointing.[27][28] A year later 3M instead issued free samples directly to consumers in Boise, Idaho, with 94 percent of those who tried them indicating they would buy the product.[27] The product was sold as "Post-its" in 1979 when the rollout introduction began,[29] and was sold across the United States[29] from April 6, 1980.[30] The following year they were launched in Canada and Europe.[31]

On its 100th anniversary, 3M officially changed its legal name to "3M Company" on April 8, 2002.[32][33]

On September 8, 2008, 3M announced an agreement to acquire Meguiar's, a car-care products company that was family-owned for over a century.[34]

On August 30, 2010, 3M announced that they had acquired Cogent Systems for $943 million.[35]

On October 13, 2010, 3M completed acquisition of Arizant Inc.[36] In December 2011, 3M completed the acquisition of the Winterthur Technology Group, a bonded abrasives company.

As of 2012, 3M was one of the 30 companies included in the Dow Jones Industrial Average, added on August 9, 1976, and was 97 on the 2011 Fortune 500 list.[37]

On January 3, 2012, it was announced that the Office and Consumer Products Division of Avery Dennison was being bought by 3M for $550 million.[38] The transaction was canceled by 3M in September 2012 amid antitrust concerns.[39]

In May 2013, 3M announced that it was selling Scientific Anglers and Ross Reels to Orvis. Ross Reels had been acquired by 3M in 2010.[40]

In March 2017, it was announced that 3M was purchasing Johnson Control International Plc's safety gear business, Scott Safety, for $2 billion.[41]

In 2017, 3M had net sales for the year of $31.657 billion, up from $30.109 billion the year before.[42] In 2018, it was reported that the company would pay $850 million to end the Minnesota water pollution case concerning perfluorochemicals.[43]

On May 25, 2018, Michael F. Roman was appointed CEO by the board of directors.[44] As of August 2018, 3M India Ltd. was the only listed 3M Company subsidiary.[45]

On December 19, 2018, 3M announced it had entered into a definitive agreement to acquire the technology business of M*Modal, for a total enterprise value of $1.0 billion.[46]

In October 2019, 3M completed the purchase of Acelity and its KCI subsidiaries worldwide for $6.7 billion, including assumption of debt and other adjustments.[47]

Environmental record

3M's Pollution Prevention Pays (3P) program was established in 1975. The program initially focused on pollution reduction at the plant level and was expanded to promote recycling and reduce waste across all divisions in 1989. By the early 1990s, approximately 2,500 3P projects decreased the company's total global pollutant generation by 50 percent and saved 3M $500–600 million by eliminating the production of waste requiring subsequent treatment.[49][50]

In 1983, the Oakdale Dump in Oakdale, Minnesota, was listed as an EPA Superfund site after significant groundwater and soil contamination by VOCs and heavy metals was uncovered.[51] The Oakdale Dump was a 3M dumping site utilized through the 1940s and 1950s.

During the 1990s and 2000s, 3M reduced releases of toxic pollutants by 99 percent and greenhouse gas emissions by 72 percent. The company earned the United States Environmental Protection Agency's Energy Star Award each year the honor was presented, as of 2012.[52]

In 1999, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency began investigating perfluorinated chemicals after receiving data on the global distribution and toxicity of perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS).[53] 3M, the former primary producer of PFOS from the U.S., announced the phase-out of PFOS, perfluorooctanoic acid, and PFOS-related product production in May 2000.[54][55] Perfluorinated compounds produced by 3M were used in non-stick cookware and stain-resistant fabrics. The Cottage Grove facility manufactured PFCs from the 1940s to 2002.[56]

In response to PFC contamination of the Mississippi River and surrounding area, 3M stated the area will be "cleaned through a combination of groundwater pump-out wells and soil sediment excavation". The restoration plan was based on an analysis of the company property and surrounding lands.[57] The on-site water treatment facility that handled the plant's post-production water was not capable of removing the PFCs, which were released into the nearby Mississippi River.[56] The clean-up cost estimate was $50 to $56 million, funded from a $147 million environmental reserve set aside in 2006.[58]

In 2008, 3M created the Renewable Energy Division within 3M's Industrial and Transportation Business to focus on Energy Generation and Energy Management.[59][60]

In late 2010, the state of Minnesota sued 3M for $5 billion in punitive damages, claiming they released PFCs—classified a toxic chemical by the EPA—into local waterways.[61] A settlement for $850 million was reached in February 2018,[62][55][63] although in 2019, 3M, along with the Chemours Company and DuPont, appeared before lawmakers to deny responsibility, with company Senior VP of Corporate Affairs Denise Rutherford arguing that the chemicals pose no human health threats at current levels and have no victims.[64]

Earplug controversy

The Combat Arms Earplugs, Version 2 (CAE v2), was developed by Aearo Technologies for U.S. military and civilian use. The CAE v2 was a double ended earplug that 3M claimed would offer users different levels of protection.[65] Between 2003 and 2015, these earplugs were standard issue to members of the U.S. military.[66] 3M acquired Aearo Technologies in 2008.[67]

In May 2016, Moldex-Metric, Inc., a 3M competitor, filed a whistleblower complaint against 3M under the False Claims Act. Moldex-Metric claimed that 3M made false claims to the U.S. government about the safety of its earplugs, and that it knew the earplugs had an inherently defective design.[68] In 2018, 3M agreed to pay $9.1 million to the U.S government to resolve the allegations, without admitting liability.[69]

Since 2018, more than 140,000 former users of the earplugs—primarily U.S. military veterans—have filed suit against 3M claiming they suffer from hearing loss, tinnitus, and other damage as a consequence of the defective design.[70]

Internal emails showed that 3M officials boasted about charging $7.63 per piece for the earplugs which cost 85 cents to produce. The company's official response indicated that the cost to the government includes R&D costs.[71]

N95 respirators and the 2020 coronavirus pandemic

The N95 respirator mask was developed by 3M and approved in 1972.[72] Being able to filter viral particulates, its use was recommended during the 2020 coronavirus pandemic but supply soon became short.[72] Much of the company's supply had already been sold prior to the outbreak.[73]

The shortages lead to the U.S. government asking 3M to stop exporting U.S.-made N95 respirator masks to Canada and to Latin American countries,[74] and President Donald Trump invoked the Defense Production Act to require 3M to prioritize orders from the federal government.[75] The dispute was resolved when 3M agreed to import more respirators, mostly from its factories in China.[75]

Operating facilities

3M's general offices, corporate research laboratories, and some division laboratories in the US are in St. Paul, Minnesota. In the United States, 3M operates 80 manufacturing facilities in 29 states, and 125 manufacturing and converting facilities in 37 countries outside the US (in 2017).[76]

In March 2016, 3M completed a 400,000-square-foot (37,000 m2) research-and-development building that cost $150 million on its Maplewood campus. Seven hundred scientists from various divisions occupy the building. They were previously scattered across the campus. 3M hopes concentrating its research and development in this manner will improve collaboration. 3M received $9.6 million in local tax increment financing and relief from state sales taxes in order to assist with development of the building.[77]

Selected factory detail information:

- Cynthiana, Kentucky, USA factory producing Post-it Notes (672 SKU) and Scotch Tape (147 SKU). It has 539 employees and was established in 1969.[78]

- Newton Aycliffe, County Durham, UK factory producing respirators for workers safety, using laser technology. It has 370 employees and recently there was an investment of £4.5 million ($7 million).[79][80]

- In Minnesota, 3M's Hutchinson facility produces products for more than half of the company's 23 divisions, as of 2019.[81] The "super hub" has manufactured adhesive bandages for Nexcare, furnace filters, and Scotch Tape, among other products.[82][83] The Cottage Grove plant is one of three operated by 3M for the production of pad conditioners, as of 2011.[84]

- 3M has operated a manufacturing plant in Columbia, Missouri since 1970. The plant has been used for the production of products including electronic components,[85][86] solar and touchscreen films, and stethoscopes. The facility received a $20 million expansion in 2012 and has approximately 400 employees.[87][88]

- 3M opened the Brookings, South Dakota plant in 1971,[89] and announced a $70 million expansion in 2014.[90] The facility manufactures more than 1,700 health care products and employs 1,100 people, as of 2018, making the plant 3M's largest focused on health care.[91] Mask production at the site increased during the 2009 swine flu pandemic, 2002–2004 SARS outbreak, 2018 California wildfires, 2019–20 Australian bushfire season, and COVID-19 pandemic.[92]

- 3M's Springfield, Missouri plant opened in 1967 and makes industrial adhesives and tapes for aerospace manufacturers. In 2017, 3M had approximately 330 employees in the metropolitan area, and announced a $40 million expansion project to upgrade the facility and redevelop another building.[93]

- In Iowa, the Ames plant makes sandpaper products and received funding from the Iowa Economic Development Authority (IEDA) for expansions in 2013 and 2018.[94][95] The Knoxville plant is among 3M's largest and produces approximately 12,000 different products, including adhesives and tapes.[96]

- 3M's Southeast Asian operations are based in Singapore, where the company has invested $1 billion over 50 years. 3M has a facility in Tuas, a manufacturing plant and Smart Urban Solutions lab in Woodlands, and a customer technical center in Yishun.[97] 3M expanded a factory in Woodlands in 2011,[84] announced a major expansion of the Tuas plant in 2016,[97] and opened new headquarters in Singapore featuring a Customer Technical Centre in 2018.[98]

- The company has operated in China since 1984,[99] and was Shanghai's first Wholly Foreign-Owned Enterprise.[100] 3M's seventh plant, and the first dedicated to health care product production, opened in Shanghai in 2007.[101] By October 2007, the company had opened an eighth manufacturing plant and technology center in Guangzhou.[99][102] 3M broke ground on its ninth manufacturing facility, for the production of photovoltaics and other renewable energy products, in Hefei in 2011.[103] 3M announced plans to construct a technology innovation center in Chengdu in 2015,[104] and opened a fifth design center in Shanghai in 2019.[105]

Leadership

Board chairs have included: William L. McKnight (1949–1966),[106][107] Bert S. Cross (1966–1970),[108][109] Harry Heltzer (1970–1975),[110] Raymond H. Herzog (1975–1980),[111] Lewis W. Lehr (1980–1986), Allen F. Jacobson (1986–1991),[112] Livio DeSimone (1991–2001),[113] James McNerney (2001–2005),[114] George W. Buckley (2005–2012),[115][116] and Inge Thulin (2012–2018).[117] Thulin continued to serve as executive chairman until current chair Michael F. Roman was appointed in 2019.[118]

3M's CEOs have included: Cross (1966–1970),[119] Heltzer (1970–1975),[110] Herzog (1975–1979),[119][120] Lehr (1979–1986),[121] Jacobson (1986–1991),[112] DeSimone (1991–2001),[113] McNerney (2001–2005),[114] Robert S. Morrison (2005, interim),[122] Buckley (2005–2012),[115][116] Thulin (2012–2018), and Roman (2018–present).[117]

3M's presidents have included: Edgar B. Ober (1905–1929),[123] McKnight (1929–1949),[107][124] Richard P. Carlton (1949–1953),[125] Herbert P. Buetow (1953–1963),[126] Cross (1963–1966),[127] Heltzer (1966–1970),[108] and Herzog (1970–1975).[128] In the late 1970s, the position was separated into roles for U.S. and international operations. The position overseeing domestic operations was first held by Lehr,[120] followed by John Pitblado from 1979 to 1981,[129] then Jacobson from 1984 to 1991.[130] James A. Thwaits led international operations starting in 1979.[129] Buckley and Thulin were president during 2005–2012,[131] and 2012–2018, respectively.[117]

See also

Further reading

- V. Huck, Brand of the tartan: the 3M story, Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1955. Early history of 3M and challenges, includes employee profiles.

- C. Rimington, From Minnesota mining and manufacturing to 3M Australia Pty Ltd (3M Australia: the Story of an Innovative Company), Sid Harta Publishers, 2013. Recollections from 3M Australia employees in context of broader organisational history.

References

- "3M Birthplace Museum", Lake County Historical Society

- "3M Company 2018 Annual Report (Form 10-K)". last10k.com. U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. February 2019.

- "3M Company 2018 Annual Report (Form 10-K)" (PDF).

- "3M Company Profile". Vault.com. Vault.com. Retrieved July 17, 2018.

- Chamaria, Neha (October 24, 2018). "Why 3M Company Finds It Hard to Keep Up With Investor Expectations". The Motley Fool. Retrieved October 10, 2019.

- "3M U.S.: Health Care". Solutions.3m.com. Retrieved March 29, 2012.

- "Who We Are – 3M US Company Information". Solutions.3m.com. Archived from the original on September 13, 2008. Retrieved July 14, 2013.

- "3M Center, Maplewood 55144 – Google Maps". Google Maps. Retrieved July 14, 2013.

- "Fortune 500 Companies 2018: Who Made the List". Fortune. Retrieved August 29, 2019.

- "3M". Company Profiles for Students. Gale. 1999. Archived from the original on May 18, 2013. Retrieved October 4, 2012.

- "900 Bush Avenue: The House that Research Built: Early Years in Saint Paul". Saint Paul Historical. Historic Saint Paul. Archived from the original on March 1, 2017. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- Prevedouros, Konstaninos; Cousins, Ian T.; Buck, Robert C.; Korzeniowski, Stephen H. (January 2006). "Sources, Fate and Transport of Perfluorocarboxylates". Environmental Science & Technology. 40 (1): 32–44. Bibcode:2006EnST...40...32P. doi:10.1021/es0512475. PMID 16433330.

- Rich, Nathaniel (January 6, 2016). "The Lawyer Who Became DuPont's Worst Nightmare". The New York Times. Retrieved January 8, 2016.

- Emmett, Edward; Shofer, Frances; Zhang, Hong; Freeman, David; Desai, Chintan; Shaw, Leslie (August 2006). "Community exposure to Perfluorooctanoate: Relationships Between Serum Concentrations and Exposure Sources". Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 48 (8): 759–70. doi:10.1097/01.jom.0000232486.07658.74. PMC 3038253. PMID 16902368.

- U.S. Patent 3,574,791

- "The Invention of Scotchgard". About.com. Retrieved August 21, 2006.

- "Inhalers become environmentally friendly". The StarPhoenix. Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. Canadian Press. February 3, 1998. p. D3 – via Newspapers.com.

- Rainsford, K. D. (2005). "The discovery, development and novel actions of nimesulide". In Rainsford, K. D. (ed.). Nimesulide: Actions and Uses. Basel: Birkhäuser Verlag. p. 4. ISBN 978-3-7643-7068-8 – via Google Books (Preview).

- Slovut, Gordon (November 19, 1985). "Space Drug". Minneapolis Star and Tribune. pp. 1A, 11A – via Newspapers.com.

- Staff (October 12, 1996). "3M urges closer look at inhalers". Kenosha News. p. C6 – via Newspapers.com.

- Anderson, Jack; Moller, Jan (January 12, 1998). "Airing out the EPA, 3M inhaler scam". The Daily Chronicle (Opinion). DeKalb, Illinois. p. 4 – via Newspapers.com.

- "3M gets approval for warts treatment". La Crosse Tribune. Associated Press. March 4, 1997. p. B3 – via Newspapers.com.

- Hill, Charles W. L.; Jones, Gareth R.; Schilling, Melissa A. (2015). Strategic Management: Theory & Cases: An Integrated Approach (11th ed.). Stamford, Connecticut: Cengage Learning. p. C-322. ISBN 978-1-285-18448-7 – via Google Books (Preview).

- "Drug units to fetch 3M $2.1 billion". The Philadelphia Inquirer (City ed.). Associated Press. November 10, 2006. p. D2 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Graceway Inc. acquires 3M's branded pharmaceuticals in $875 million deal". Johnson City Press. NET News Service. November 10, 2006. p. 7C – via Newspapers.com.

- "1978 3M Digital Audio Mastering System-Mix Inducts 3M Mastering System Into 2007 TECnology Hall of Fame". Mixonline.com. September 1, 2007. Archived from the original on March 13, 2012. Retrieved March 29, 2012.

- Fry, Art; Silver, Spencer. "First Person: 'We invented the Post-It Note'". FT Magazine. Retrieved December 20, 2010.

- "TV News Headlines - Yahoo TV". Yahoo TV.

- Stelter, Brian (December 24, 2010). "Right on the $800,000 Question, They Lost Anyway". The New York Times. Retrieved September 21, 2015.

- "Spencer Silver". Retrieved December 24, 2010.

- "The Evolution of the Post-it Note". 3M. Retrieved February 13, 2010.

- "Timeline of 3M History". 3M. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- "3M raises 1Q estimates". CNN/Money. April 4, 2002. Archived from the original on June 12, 2002. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- "3M to Acquire Meguiar's, Inc". Meguiar's Online. September 8, 2008. Retrieved March 29, 2012.

- Sayer, Peter (August 30, 2010). "3M Offers $943M for Biometric Security Vendor Cogent Systems". PC World. Retrieved February 16, 2013.

- "3M Completes Acquisition of Arizant Inc". 3M. Retrieved October 15, 2010.

- "Fortune 500 2011: Fortune 1,000 Companies 1–100". Fortune Magazine. Archived from the original on January 2, 2012. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- "3M buys office supply unit of Avery Dennison for $550M | Minnesota Public Radio News". Minnesota.publicradio.org. January 3, 2012. Retrieved March 29, 2012.

- Robinson, Will (September 5, 2012). "3M Drops Avery Dennison Unit Buyout Amid Antitrust Worry". Bloomberg News. Retrieved April 14, 2014.

- Anderson, Dennis (May 2, 2013). "3M to sell two fly-fishing businesses to Orvis". StarTribune. Minneapolis.

- "3M to buy Johnson Controls' safety gear business for $2 billion". Reuters. March 16, 2017. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- "Why Is 3M Company (MMM) Down 6.1% Since its Last Earnings Report?". Yahoo. February 26, 2018.

- "3M will pay $850 million in Minnesota to end water pollution case". CNN. February 21, 2018.

- "3M COMPANY (NYSE:MMM) Files An 8-K Departure of Directors or Certain Officers; Election of Directors; Appointment of Certain Officers; Compensatory Arrangements of Certain Officers - Market Exclusive". marketexclusive.com. Retrieved May 25, 2018.

- "3M India: Dial M for efficiency - Forbes India". Forbes India.

- "3M to Acquire M*Modal's Technology Business". businesswire.com. December 19, 2018. Retrieved October 28, 2019.

- "3M Completes Acquisition of Acelity, Inc". 3M News | United States. Retrieved October 19, 2019.

- "Target Lights Create Evolving Minneapolis Landmark". Minneapolis/St. Paul Business Journal. April 11, 2003.

- Holusha, John (February 3, 1991). "Hutchinson No Longer Holds Its Nose". The New York Times. Retrieved January 8, 2020.

- Oster, Patrick (January 23, 1993). "GOING 'GREEN' AND THE BOTTOM LINE". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 8, 2020.

- "Superfund Site: Oakdale Dump Oakdale, MN". U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved July 18, 2017.

- Winston, Andrew (May 15, 2012). "3M's Sustainability Innovation Machine". Harvard Business Review. Retrieved January 8, 2020.

- Ullah, Aziz (October 2006). "The Fluorochemical Dilemma: What the PFOS/PFOA Fuss Is All About" (PDF). Cleaning & Restoration. Retrieved October 25, 2008.

- "PFOS-PFOA Information: What is 3M Doing?". 3M. Archived from the original on September 22, 2008. Retrieved October 25, 2008.

- Fellner, Carrie (June 16, 2018). "Toxic Secrets: Professor 'bragged about burying bad science' on 3M chemicals". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved June 25, 2018.

- "Perfluorochemicals and the 3M Cottage Grove Facility: Minnesota Dept. Of Health". Health.state.mn.us. December 15, 2011. Archived from the original on April 29, 2012. Retrieved March 29, 2012.

- "Health Consultation: 3M Chemolite: Perfluorochemicals Releases at the 3M – Cottage Grove Facility Minnesota Department of Health, Jan. 2005" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 8, 2016. Retrieved March 29, 2012.

- "State's lawsuit against 3M over PFCs at crossroads". StarTribune. Minneapolis. January 13, 2014. Retrieved May 20, 2015.

- "3M U.S.: Sustainability at 3M". Solutions.3m.com. Retrieved March 29, 2012.

- "3M Forms Renewable Energy Division | Renewable Energy News Article". Renewableenergyworld.com. February 4, 2009. Retrieved March 29, 2012.

- "Minnesota sues 3M over pollution claims". Reuters. December 30, 2010.

- Dunbar, Elzabeth; Marohn, Kirsti (February 20, 2018). "Minnesota settles water pollution suit against 3M for $850 million". MPR News. Retrieved February 20, 2018.

- Fellner, Carrie (June 15, 2018). "Toxic Secrets: The town that 3M built - where kids are dying of cancer". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved June 25, 2018.

- Holden, Emily (September 11, 2019). "Companies deny responsibility for toxic 'forever chemicals' contamination". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved October 10, 2019.

- Hinds, Haley (October 29, 2019). "Veterans sue 3M, claim faulty ear plugs caused hearing damage". FOX 13 News. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- "Vets Tormented by Hearing Loss Face 3M in Earplug Mass Lawsuit". Bloomberg Government. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- "3M to Acquire Aearo Technologies Inc., Global Leader in Personal Protection Equipment". 3M News | United States. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- "Contractor settles for $9.1 million after providing defective earplugs for servicemembers". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- "3M Company Agrees to Pay $9.1 Million to Resolve Allegations That it Supplied the United States With Defective Dual-Ended Combat Arms Earplugs". www.justice.gov. July 26, 2018. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- Robinson, Kevin. "Pensacola judge weighing lawsuit claiming 3M earplugs damaged veterans' hearing". Pensacola News Journal. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- "3M billed government $7.63 for 85-cent earplugs. It now has $1 billion COVID contract". McClatchy. 2020.

- Wilson, Mark (March 24, 2020). "The untold origin story of the N95 mask". Fast Company. Retrieved March 27, 2020.

- "The World Needs Masks. China Makes Them — But Has Been Hoarding Them". The New York Times. March 16, 2020.

- "Trump 'wants to stop mask exports to Canada'". BBC News. April 3, 2020. Retrieved April 4, 2020.

- "3M will import masks from China for U.S. to resolve dispute with the Trump administration". The New York Times. April 6, 2020.

- 3M Company 2018 Annual Report on Form 10-K (PDF) (Report). p. 13. Retrieved June 4, 2018.

- DePass, Dee (March 11, 2016). "3M Co. opens new $150 million R&D lab in Maplewood". StarTribune. Minneapolis. Retrieved December 4, 2017.

- "3M US : Cynthiana, Kentucky Plant : Home". 3M Company. Retrieved September 21, 2014.

- Johnson, Deborah (July 16, 2008). "'World-class' site to benefit from £4.5m". The Northern Echo. Darlington, England. Retrieved March 29, 2012.

- McAteer, Owen (June 17, 2008). "Latest Technology Improves Production". The Northern Echo. Darlington, England. Retrieved March 29, 2012.

- Hufford, Austen (April 11, 2019). "3M Sticks Together, as Rivals Break Apart". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved April 14, 2020.

- Marcus, Alfred A.; Geffen, Donald A.; Sexton, Ken (September 30, 2010). Reinventing Environmental Regulation: Lessons from Project XL. Routledge. Retrieved March 30, 2020.

- Hagerty, James R. (May 16, 2012). "3M Begins Untangling Its 'Hairballs'". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved March 30, 2020.

- Cable, Josh (July 12, 2011). "3M Completes Expansion in Asia". IndustryWeek. Retrieved March 30, 2020.

- Malone, Scott (September 27, 2007). "3M to lay off 240 workers at Missouri facility". Reuters. Retrieved March 30, 2020.

- Currier, Joel; Ryan, Erin (July 18, 2008). "3M announces record layoffs". Columbia Missourian. Retrieved March 30, 2020.

- Lauzon, Michael (March 28, 2013). "3M may expand solar films plant in Missouri". Plastics News. Retrieved April 18, 2020.

- Barker, Jacob (March 25, 2013). "3M's expansion might add 50 jobs". Columbia Daily Tribune. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- Allen, Brian (December 5, 2017). "3M, Walmart mark economic successes in Brookings". KSFY-TV. Retrieved March 30, 2020.

- Schwan, Jodi (October 2, 2014). "3M stokes boom in Brookings with $70M deal". Argus Leader. Retrieved March 30, 2020.

- Dennis, Tom (August 1, 2018). "Makers: Manufacturing matters, and these three standout regional companies show why". Prairie Business. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- Sneve, Sioux Falls Argus Leader, Joe (February 28, 2020). "Coronavirus has Sioux Falls stores struggling to keep respiratory masks stocked". Argus Leader. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- Gounley, Thomas (May 24, 2017). "Manufacturer 3M makes planned Springfield expansion official". Springfield News-Leader. Retrieved March 30, 2020.

- "3M receives state aid for expansion of Ames plant". Ames Tribune. January 18, 2013. Retrieved March 30, 2020.

- "State awards aid to Story County businesses". Ames Tribune. September 21, 2018. Retrieved March 30, 2020.

- Finan, Pat (March 13, 2018). "3M expansion will near $35 million, bring 30 jobs". Journal-Express. Retrieved March 30, 2020.

- "3M to spend $135m to expand Tuas plant". The Straits Times. July 26, 2016. Retrieved October 28, 2019.

- Tan, Elyssa (June 28, 2018). "3M opens new headquarters in Singapore". Business Times. Retrieved October 28, 2019.

- "3M to double China manufacturing capacity in five years". MarketWatch. Dow Jones & Company. October 29, 2007. Retrieved October 28, 2019.

- Xin, Zheng (September 21, 2018). "3M to invest in safety, healthcare sector". China Daily. Retrieved October 28, 2019.

- "3M's Seventh Plant in China to Be Its First for Health Care". The Wall Street Journal. February 7, 2007. Retrieved October 28, 2019.

- Quanlin, Qiu (July 20, 2007). "3M starts new plant in GZ". China Daily. Retrieved October 28, 2019.

- "3M Adds Solar Products Mfg. Plant in China". Twin Cities Business. April 8, 2011. Retrieved October 28, 2019.

- DePass, Dee (March 20, 2015). "3M to open tech center in western China". Star Tribune. Retrieved October 28, 2019.

- "3M opens design center in Shanghai". China Internet Information Center. March 13, 2019. Retrieved October 28, 2019.

- Cummings, Judith (March 5, 1978). "William L. McKnight, Who Built A Sandpaper Company Into 3M". The New York Times. Retrieved August 28, 2019.

He had retired as chairman of the board of 3M in 1966, but had continued to serve on the board and received the title of director emeritus in 1973.

- Lukas, Paul; Overfelt, Maggie (April 1, 2003). "3M A Mining Company Built on a Mistake Stick It Out Until a Young Man Came Along with Ideas About How to Tape Those Blunders Together as Innovations--Leading to Decades of Growth". CNN Money. Retrieved August 28, 2019.

When he became general manager in 1914, 3M was a $264,000 company; by the time he was made president in 1929, annual revenues were $5.5 million; in 1943, 3M generated $47.2 million, and by the time of McKnight's retirement as chairman in 1966, he had grown 3M into a $1.15 billion operation.

- "Heltzer and Herzog Move to Top at 3M". Commercial West. 140: 17. August 22, 1970. Retrieved August 28, 2019.

- Berry, John F.; Jones, William H. (May 18, 1977). "Boxes of SEC Documents Reveal Secret Dealings". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 28, 2019.

- Martin, Douglas (September 28, 2005). "Harry Heltzer, 94, Inventor of Reflective Signs, Dies". The New York Times. Retrieved August 28, 2019.

Nearly a third of that increase came after he rose from president to chairman and chief executive in October 1970.

- "3M Says Reputation Is Still Strong One". The New York Times. May 14, 1975. Retrieved August 28, 2019.

Mr. Herzog was elected chairman at a board meeting after the stockholder session, succeeding Harry Heltzer. Mr. Herzog will continue as president and chief executive officer.

- Schmitt, Eric (February 11, 1986). "Business People; 2 Top 3M Posts Go to Domestic Head". The New York Times. Retrieved August 28, 2019.

The Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Company announced yesterday that Allen F. Jacobson, president of the concern's domestic operations, had been named chairman and chief executive, effective March 1.

- Hagerty, James R. (January 18, 2017). "Livio DeSimone, a Former 3M CEO, Dies at 80". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved August 28, 2019.

He served as chairman and CEO from 1991 to 2001.

- Lublin, Joann; Murray, Matthew; Hallinan, Joe (December 5, 2000). "General Electric's McNerney Will Become 3M Chairman". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved August 28, 2019.

- Dash, Eric (December 8, 2005). "3M Finds Chief Without Reaching for a Star". The New York Times. Retrieved August 28, 2019.

And yesterday, 3M named George W. Buckley, the low-profile leader of the Brunswick Corporation, as its new chairman and chief executive.

- "3M CEO Buckley to retire; Thulin to succeed him". Reuters. February 8, 2012. Retrieved August 28, 2019.

- "3M appoints Michael Roman as CEO; Inge Thulin will take new position as executive chairman of the board". CNBC. March 5, 2018. Retrieved August 28, 2019.

Thulin has served as 3M's chairman of the board, president and chief executive officer since 2012.

- Ruvo, Christopher (February 7, 2019). "Thulin To Retire As 3M Chairman". Advertising Specialty Institute. Retrieved August 29, 2019.

- Jensen, Michael C. (March 9, 1975). "How 3M Got Tangled Up in Politics". The New York Times. Retrieved August 28, 2019.

Bert S. Cross, who was chairman and chief executive of 3M from 1966 to 1970, and a board member thereafter, will not seek re‐election to the board where he serves as chairman of the finance committee.

- "Herzog Shifts His Role at 3M". The New York Times. February 13, 1979. Retrieved August 28, 2019.

- Eccher, Marino (August 3, 2016). "For former 3M CEO Lew Lehr, mistakes were stepping stones". St. Paul Pioneer Press. Retrieved August 28, 2019.

Lehr was chief executive of 3M from 1979 to 1986.

- Schmeltzer, John (July 1, 2005). "Quaker Oats ex-chief takes control at 3M". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved August 28, 2019.

- Bustin, Greg (2019). How Leaders Decide: A Timeless Guide to Making Tough Choices. Naperville, Illinois: Sourcebooks. p. 41. ISBN 9781492667599. Retrieved August 28, 2019.

At the May 1905 annual meeting, Over was named 3M's new president. Apart from one three-year break, Over served as president until 1929—the first eleven years without compensation.

- Byrne, Harlan S. (July 3, 2000). "A Changed Giant". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved August 28, 2019.

The patient approach may have originated with W. L. McKnight, a legendary CEO who joined the company in 1907 and became president in 1929.

- Betz, Frederick (2011). 3M Diversifies Through Innovation. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. p. 154. ISBN 9780470927571. Retrieved August 28, 2019.

The award was named after Richard Carlton, president of 3M from 1949 to 1953.

- "Herbert Buetow, Manufacturer, 73". The New York Times. January 11, 1972. Retrieved August 28, 2019.

He was president of 3‐M from 1953 to 1963 and retired from its board in 1968.

- "3M Names Heltzer President and Cross as New Chairman; 2 High Positions Are Filled by 3M". The New York Times. August 11, 1966. Retrieved August 28, 2019.

- "Raymond Herzog, Helped Start 3M Copier Business". Sun-Sentinel. July 23, 1997. Retrieved August 28, 2019.

He was president of the company from 1970 until 1975, when he became chairman and chief executive.

- Sloane, Leonard (August 17, 1981). "Business People". The New York Times. Retrieved August 28, 2019.

- Gilpin, Kenneth (November 5, 1984). "Business People; 3M Fills Top Post at Major Division". The New York Times. Retrieved August 28, 2019.

Mr. Jacobson... fills a post that has been vacant since the end of 1981, when John Pitblado retired.

- Dash, Eric (December 7, 2005). "3M Names Chief, Ending 5-Month Search". The New York Times. Retrieved August 28, 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 3M. |

- Business data for 3M:

- Google Local's satellite image of 3M head office campus

- 3M Global Company Profile from Transnationale.org

- Minnesota Department of Health on the Oakdale Dump Superfund Site

- The historical records of the 3M Company are available for research use at the Minnesota Historical Society