Düzdidil Kadın

Düzdidil Kadın (Ottoman Turkish: دزددل قادین, from Persian دزد دل duzd-i dil meaning "thief of hearts"; c. 1825 – 18 August 1845) was the third wife of Sultan Abdulmejid I of the Ottoman Empire.

| Düzdidil Kadın | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Born | Ayşe Dişan c. 1825 North Caucasus | ||||

| Died | 18 August 1845 (aged 19–20) Constantinople, Ottoman Empire (present day Istanbul, Turkey) | ||||

| Burial | Imperial ladies Mausoleum, New Mosque, Istanbul | ||||

| Spouse | |||||

| Issue Among others | |||||

| |||||

| House | Dişan (by birth) Ottoman (by marriage) | ||||

| Father | Şıhım Dişan | ||||

| Mother | Princess Çaçba | ||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||

Early life

Düzdidil Kadın was born in 1825[1] in North Caucasus. Born as Ayşe Dişan, she was a member of Ubykh family, Dişan. Her father was Şıhım Bey Dişan and her mother was an Abkhazian princess belonging to Shervashidze.[2]

Upon Yahya Bey's decision, Ayşe had been brought to Istanbul as a young child, where she entrusted to the imperial harem, along with her nanny Cinan Hanım, and a maid Emine Hanım. Here her name according to the custom of the Ottoman court was changed to Düzdidil.[2]

Marriage

Düzdidil married Abdulmejid in 1839, and was given the title of "Third Consort".[3] On 31 May 1840, she gave birth to the Abdulmejid's first child and daughter, Mevhibe Sultan in the Old Çırağan Palace. The princess died on 9 February 1841.[4]

On 13 October 1841, she gave birth to twins, Neyyire Sultan[5] and Münire Sultan in the Old Beşiktaş Palace. The princesses died two years later on 18 December 1843.[6]

On 17 August 1843, she gave birth to her fourth child, Cemile Sultan in the Old Beylerbeyi Palace.[7] On 23 February 1845, she gave birth to her fifth child, Samiye Sultan[5] in the Topkapı Palace. The princess died two months later on 18 April 1845.[8]

Charles White, who visited Istanbul in 1843, wrote following about her:

The third...is cited as remarkable for her beauty, and not less so for her haughty and wayward disposition.[9]

Death

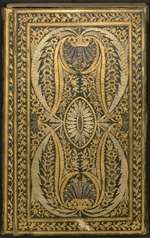

Düzdidil had fallen victim to the epidemic of tuberculosis then raging in Istanbul. A luxuriously decorated prayer book was commissioned around 1844 for her. As was fitting for her position, the prayer book was lavishly ornate.[10]

She died on 18 August 1845, and was buried in the mausoleum of the imperial ladies at the New Mosque Istanbul.[11][3][1] Cemile Sultan was only two years old when Düzdidil died. She was adopted by another of Sultan Abdulmejid's wives, Perestu Kadın,[5] who was also the adoptive mother one of her half brothers, Sultan Abdul Hamid II.[12]

After her death, her nanny, Cinan Hanım, went back to Caucasus,[13] while her maid, Emine Hanım, served in the imperial harem for sometime, after which she married and left the palace.[14]

Issue

Together with Abdulmejid, Düzdidil had five daughters:

- Mevhibe Sultan (Çırağan Palace, 31 May 1840 – Istanbul, 9 February 1841, buried in Tomb of Abdul Hamid I);

- Neyyire Sultan (Beşiktaş Palace – 13 October 1841 - Istanbul, 18 December 1843, buried in Nuruosmaniye Mosque);

- Münire Sultan (Beşiktaş Palace, 13 October 1841 – Istanbul, 18 December 1843, buried in Nuruosmaniye Mosque);

- Cemile Sultan (Beylerbeyi Palace, 17 August 1843 – Erenköy Palace, 26 February 1915, buried in Abdulmejid I Mausoleum, Fatih);

- Samiye Sultan (Topkapı Palace, 23 February 1845, – Istanbul, 18 April 1845, buried in New Mosque);

References

- Brookes 2010, p. 280.

- Açba 2007, p. 51.

- Uluçay 2011, p. 206.

- Uluçay 2011, p. 217.

- Sakaoğlu 2008, p. 599.

- Uluçay 2011, p. 220, 225.

- Uluçay 2011, p. 221.

- Uluçay 2011, p. 225.

- Charles White (1846). Three years in Constantinople; or, Domestic manners of the Turks in 1844. London, H. Colburn. p. 10.

- Rebhan, Helga (2010). Die Wunder der Schöpfung: Handschriften der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek aus dem islamischen Kulturkreis. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 79. ISBN 978-3-880-08005-8.

- Açba 2007, p. 52.

- Brookes 2010, p. 279.

- Açba 2007, p. 52 n. 23.

- Açba 2007, p. 51 n. 22.

Sources

- Uluçay, M. Çağatay (2011). Padişahların kadınları ve kızları. Ötüken. ISBN 978-9-754-37840-5.

- Açba, Harun (2007). Kadın efendiler: 1839-1924. Profil. ISBN 978-9-759-96109-1.

- Sakaoğlu, Necdet (2008). Bu Mülkün Kadın Sultanları: Vâlide Sultanlar, Hâtunlar, Hasekiler, Kandınefendiler, Sultanefendiler. Oğlak Yayıncılık. ISBN 978-6-051-71079-2.

- The Concubine, the Princess, and the Teacher: Voices from the Ottoman Harem. University of Texas Press. 2010. ISBN 978-0-292-78335-5.