Cyclecar

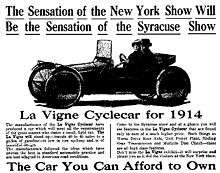

A cyclecar was a type of small, lightweight and inexpensive car manufactured in Europe and the United States between 1910 and the early 1920s. The purpose of cyclecars was to fill a gap in the market between the motorcycle and the car.[1]

The demise of cyclecars was due to larger cars – such as the Citroën Type C, Austin 7 and Morris Cowley – becoming more affordable. Small, inexpensive vehicles reappeared after World War II, and were known as microcars.

Characteristics

.jpg)

Cyclecars were propelled by engines with a single cylinder or V-twin configuration (or occasionally a four cylinder engine), which were often air-cooled.[2] Sometimes motorcycle engines were used, in which case the motorcycle gearbox was also used.

All cyclecars were required to have clutches and variable gears. This requirement could be fulfilled by even the simplest devices such as provision for slipping the belt on the pulley to act as a clutch, and varying of the pulley diameter to change the gear ratio. Methods such as belt drive or chain drive were used to transmit power to the drive wheel(s),[3] often to one wheel only, so that a differential was not required.

The bodies were lightweight and sometimes offered minimal weather protection or comfort features.

The rise of cyclecars was a direct result of reduced taxation both for registration and annual licences of lightweight small-engined cars. On 14 December 1912, at a meeting of the Federation Internationale des Clubs Moto Cycliste, it was formally decided that there should be an international classification of cyclecars to be accepted by the United Kingdom, Canada, United States, France, The Netherlands, Belgium, Italy, Austria and Germany. As a result of this meeting, the following classes of cyclecars were defined:

| Class | Max. weight | Max. displacement | Min. tyre section |

|---|---|---|---|

| Large | 350 kg (772 lb) | 1,100 cc (67 cu in) | 60 mm (2.4 in) |

| Small | 150 kg (331 lb) | 750 cc (46 cu in) | 55 mm (2.2 in) |

Origins

From 1898 to 1910, automobile production quickly expanded. Light cars of that era were commonly known as voiturettes. The smaller cyclecars appeared around 1910 with a boom shortly before the outbreak of the First World War, with Temple Press launching The Cyclecar magazine on 27 November 1912 (later renamed The Light Car and Cyclecar), and the formation of the Cyclecar Club (which later evolved into British Automobile Racing Club). From 1912, the Motor Cycle show at Olympia became the Motor Cycle and Cycle Car Show.

The number of cyclecar manufacturers was less than a dozen in each of the UK and France in 1911, but by 1914, there were over 100 manufacturers in each country, as well as others in Germany, Austria and other European countries.[4] By 1912, the A.C. Sociable was described as "one of the most popular cycle cars on the road, both for pleasure and for business",[5] though another source states that the "Humberette" was the most popular of cycle cars at that time.[6] Many of the numerous makes were relatively short-lived, but several brands achieved greater longevity, including Bédélia (1910-1925), GN (1910-1923) and Morgan (1910–present).[7]

Demise

By the early 1920s, the days of the cyclecar were numbered. Mass producers, such as Ford, were able to reduce their prices to undercut those of the usually small cyclecar makers. Similar affordable cars were offered in Europe, such as the Citroën 5CV, Austin 7 or Morris Cowley.

The cyclecar boom was over. The majority of cyclecar manufacturers closed down. Some companies such as Chater-Lea survived by returning to the manufacture of motorcycles.

After the Second World War, small, economic cars were again in demand and a new set of manufacturers appeared. The cyclecar name did not reappear however, and the cars were called microcars by enthusiasts and bubble cars by the general population.

Motor racing

Several motor racing events for cyclecars were run between 1913 and 1920. The first race dedicated to cyclecars was organised by the Automobile Club de France in 1913, followed by a Cyclecar GP at Le Mans in 1920. The Auto Cycle Union was to have introduced cycle car racing on the Isle of Man in September 1914, but the race was abandoned due to the onset of the war.[8]

List of cyclecars by country

Argentina

- Viglione

Belgium

- CAP (de:CAP)

- SCH

Canada

- Baby Car

- Campagna T-Rex

- Dart Cycle Car Co

- Glen Motor Company

- Gramm

- Holden-Morgan

- Welker-Doerr

Czechoslovakia

- Aero 500

- Novo

- Vaja

Denmark

France

- Able

- Ajams

- Ajax

- Alcyon

- Amilcar

- Allain et Niguet

(AN) (de:Allain et Niguet) - Ardex

- Arzac

- Astatic

- Astra

- Austral

- Auto Practique (de:Auto Pratique)

- Automobillette (de:Automobilette)

- Autorette (de:Autorette)

- Bédélia

- Benjamin (de:Benjamin)

- Billard (de:Billard)

- Blériot Aéronautique (de:Blériot Aéronautique)

- Benova

- Bollack Netter and Co (B.N.C.)

- Bucciali (Buc)

- Causan

- Coadou et Fleury

- Contal

- (Coudert), see

Lurquin-Coudert - Croissant (de:Croissant)

- De Sanzy

- D'Yrsan

- D'Aux (de:D’Aux)

- De Marçay (de:De Marçay)

- Derby

- Deschamp (de:Deschamps et Cie)

- Désert et de Font-Réault (de:Désert et de Font-Réault)

- Dorey (de:Dorey)

- Eclair (de:Eclair)

- Einaudi (de:Cyclecars Einaudi)

- Elfe

- Emeraude (de:Emeraude)

- G.A.M. (de:G.A.M.)

- G.A.R. (de:G.A.R.)

- Gauthier (de:Gauthier et Cie)

- Griffon (de:Établissements Griffon)

- Grouesy

- HP (de:H.P.)

- Huffit

- Ipsi

- Jack Sport

- Janoir

- Janémian

- JG Sport

- Jouvie

- Julien (de:Julien)

- La Confortable

- La Flèche (de:La Flèche)

- La Perle (de:La Perle)

- La Roulette

- La Violette (de:La Violette)

- Lacour (de:Lacour et Cie)

- Laetitia

- Lafitte

- L.B. (de:L.B.)

- Le Cabri

- Le Favori

- Le Méhari (de:Le Méhari)

- Le Roitelet

- Lurquin-Coudert

- Major (de:Cyclecars Major)

- Marguerite Typ A (de:Marguerite Typ A)

- Marr (de:Max)

- Max (de:Max)

- Molla (de:Molla et Cie)

- Micron (de:Automobiles Micron)

- Molla (de:Molla et Cie)

- Monitor

- Mourre (de:Mourre)

- Noël (de:Noël)

- Orial (de:Orial)

- Patri (de:Patri)

- Pégase (de:Pégase)

- Pestourie et Planchon (de:Pestourie et Planchon)

- Phébus (de:Cyclecars Phébus)

- Quo Vadis

- Rally

- Revol (de:Revol)

- Roll

- Salmson

- Santax

- Sénéchal

- SICAM (de:SICAM)

- SIMA-Violet (de:Sima-Violet)

- Sphinx (de:Sphinx Automobiles)

- Spidos (de:Sphinx Automobiles)

- Super (de:Super)

- Tholomé (de:Tholomé)

- Tic-Tac (de:Tic-Tac)

- Tom Pouce (de:Tom Pouce)

- Utilis (de:Utilis)

- Vaillant

- Villard

- Violet-Bogey (de:Violet-Bogey)

- Violette

- Viratelle (de:Viratelle)

- Virus

- Weler (de:Weler)

- Zénia (de:Zénia)

- Zévaco (de:Zévaco)

Germany

- Arimofa

- Bootswerft Zeppelinhafen

(B.Z.) (de:Bootswerft Zeppelinhafen) - Cyklon

- Dehn (de:Fahrzeug- und Maschinenfabrik K. C. Dehn)

- Grade

- Koco

- Minimus Fahrzeugwerk (de:Minimus Fahrzeugwerk)

- Pluto

- Slaby-Beringer (de:Slaby-Beringer)

- Spinell

- Staiger

- Zaschka

Greece

Italy

- Amilcar Italiana

- Anzani

- Baroso

(Officine Barosso)(de:Officine Barosso) - C.I.P.

(Cyclecar Italiana Petromilli)(de:Cyclecar Italiana Petromilli) - Della Ferrera

(Fratelli Della Ferrera)(de:Fratelli Della Ferrera) - Marino

- Meldi

(Officine Meccanica Giuseppe Meldi)(de:Officine Meccanica Giuseppe Meldi) - San Giusto

(S.A. San Giusto)(de:S.A. San Giusto) - SIC

(Società Italiana Cyclecars) (de:Società Italiana Cyclecars) - Vaghi

(Motovetturette Vaghi)(de:Motovetturette Vaghi)

Poland

- SKAF

Spain

- Alvarez

- David

- Izaro

- JBR

- Salvador

Sweden

- Mascot

- Self

Switzerland

- Moser (Fritz Moser, Fabrique d’Automobiles et Motocyclettes) (de:Fritz Moser)

- Speidel

United Kingdom

- AC (Auto Carriers Ltd)

- Adamson

- Aerocar

- Allwyn

- Alvechurch

- Amazon

- Archer

- Armstrong

- Athmac

- Atomette

- Autotrix

- AV

- Baby Blake

- Baker & Dale

- Bantam

- Barnard

- Baughan

- Beacon Motors

- Bell

- Black Prince

- Blériot-Whippet

- Bound

- Bow-V-Car

- BPD

- Bradwell

- Britannia

- Broadway

- Buckingham

- Cambro

- Campion

- Corfield & Hurle (de:C & H)

- Carden

- Carlette

- Carter

- Castle Three

- CFB

- CFL

- Chater-Lea

- Chota

- Coventry Premier

- Coventry Victor

- Crescent

- Cripps

- Crompton

- Crouch

- Cumbria Motors

- CWS

- Cyclar

- Dallison

- Day-Leeds

- Dayton

- Dennis

- Dewcar

- Douglas

- D'Ultra (D-Ultra)

- Duocar

- Dursley-Pedersen

- Economic

- Edmond

- Edmund

- Edwards

- EYME

- GB

- Gerald (de:Gerald Cyclecar)

- Gibbons

- Gillyard

- Glover

- GN

- Gnome

- Gordon (1912-1914)

- Grahame-White

- Guildford

- GWK

- Hampton

- HCE

- Heybourn

- Hill & Stanier

- HMC

- Howard

- Howett

- HP

- Humberette

- Imperial

- Invicta

- Jappic

- JBS

- Jewel

- Jones

- Kendall

- LAD

- La Rapide

- Lambert

- LEC

- Lecoy

- Lester Solus

- Lington

- LM (Little Midland)

- Matchless

- Marcus

- Marlborough (Anglo-French car)

- Mead & Deakin (Medea)

- Medinger

(de:Medinger Cars & Engine) - Menley

- Meteorite Cars

(de:Meteorite Cars) - Metro-Tyler (de:Metro-Tyler)

- Morgan

- New Hudson

- Nomad Cars (de:Nomad Cars)

- Northstar (de:North Star Works)

- Norma

- Paragon (de:Paragon)

- Pickering, Darley & Allday (PDA)

- Pearson & Cox

- Perry

- Premier Motor

(PMC) (de:Premier Motor) - Princess

- Projecta (de:Projecta)

- Pyramid (de:Pyramid)

- Ranger (de:Ranger Cyclecar)

- Rex

- Richardson (1903)

- Richardson (1919)

- Robertson

- Robinson & Price

- Rollo

- Royal Ruby

- Rene Tondeur (RTC) (de:Rene Tondeur)

- Rudge-Whitworth

- J. A. Ryley (de:J. A. Ryley)

- Simplic

- Skeoch

- Speedy (de:Speedy)

- Sterling

- Stoneleigh

- Swift

- Tamplin

- T.B.

- Tiny

- Turner

- Unique (de:Unique)

- VAL

- Vee Gee

- Victor

- Warne

- Warren-Lambert

- Westall

- Wherwell

- Whitgift

(de:Whitgift) - Wilbrook

- Willis

- Winson

- Wooler

- Wrigley

- WSC

- Winter

- Woodrow

- Xtra

- Zendik

United States

- American

- Argo

- Arrow

- Asheville

- Buick prototype built by Walter Lorenzo Marr[9]

- Briggs & Stratton Flyer

see Smith Flyer - Bull Moose-Cutting Automobile Company

Baby Moose

(de:Bull Moose-Cutting Automobile Company) - Burrows

(1914 Ripley NY) - Car-Nation

- Ceco

(Continental Engineering Company)

(de:Continental Engineering Company) - Coey

- Comet

- Continental Engine Manufacturing Company

(de:Continental Engine Manufacturing Company) - Corbin Motors

- Cycle-Car

- Cyclops (de:Cyclops Cyclecar)

- Dayton (de:Dayton Cyclecar)

- De La Vergne

- Delco

- Dodo

- Dudly Bug

- Economy car

- EIM

- Engler

- Falcon

- Fenton

- Geneva

- Greyhound

- Hall

- Hanover

- Hawk

- Hawkins

- Hoosier Scout

- IMP

- JPL

- Kearns LuLu

- Keller (de:Keller Cyclecar)

- La Vigne

- Limit

- Logan

- Malcolm Jones

- Merz

- Michaelson

- Mecca

- Mercury

- Motor Bob

- O-We-Go

- Pacific

- Pioneer

- Portland

- Post

- Prigg

- Puritan

- Real

- Rex

- Saginaw

- Scripps-Booth

- Smith Flyer

- Trumbull

- Twombly

- Vixen

- Winthur

- Wizzard

- Woods

- Xenia

- Yankee

See also

References

- "Special Features / Cyclecars". www.carhistory4u.com. Archived from the original on 22 June 2011. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

- "American Cyclecar Manufacturers". www.american-automobiles.com. Retrieved 25 December 2018.

- "Motoring memories - Cyclecars". www.autos.ca. Retrieved 25 December 2018.

- The Light Car, C.F.Caunter. HMSO 1970 (first published 1958)

- The Motor Cycle and Cycle Car Show, The Automotor magazine, 30 November 1912, p1448

- The Car and British Society, Sean O'Connell, Manchester University Press, 1998, p17

- "The Competitors in Trials and Races, the Rivals in Business". www.morgan3w.de. Retrieved 25 December 2018.

- "Current Chat", The Motor Cycle magazine, 3 September 1914, p300

- Kimes, Beverly Rae (2007). Walter L. Marr, Buick's Amazing Engineer. Boston: Racemaker Press.

Further reading

- Worthington-Williams, Michael (1981). From cyclecar to microcar the story of the cyclecar movement. Beaulieu Books. ISBN 0-901564-54-0.

- David Thirlby (2002). Minimal Motoring: From Cyclecar to Microcar. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0-7524-2367-3.