Cursing the fig tree

The cursing of the fig tree is an incident in the gospels, presented in Mark and Matthew as a miracle in connection with the entry into Jerusalem,[1] and in Luke as a parable.[2] (The gospel of John omits it entirely and shifts the incident with which it is connected, the cleansing of the temple, from the end of Jesus' career to the beginning.)[2] The image is taken from the Old Testament symbol of the fig tree representing Israel, and the cursing of the fig tree in Mark and Matthew and the parallel story in Luke are thus symbolically directed against the Jews, who have not accepted Jesus as king.[3][4]

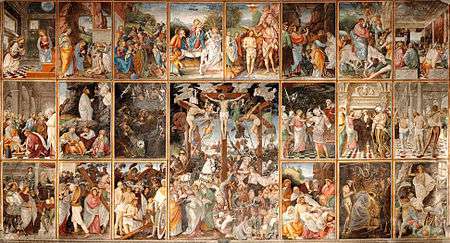

| Events in the |

| Life of Jesus according to the canonical gospels |

|---|

|

|

In rest of the NT |

|

Portals: |

Commentary

Most scholars believe that Mark was the first gospel and was used as a source by the authors of Matthew and Luke.[5] In the Jewish scriptures the people of Israel are sometimes represented as figs on a fig tree (Hosea 9:10, Jeremiah 24), or a fig tree that bears no fruit (Jeremiah 8:13), and in Micah 4:4 the age of the messiah is pictured as one in which each man would sit under his fig tree without fear; the cursing of the fig tree in Mark and Matthew and the parallel story in Luke are thus symbolically directed against the Jews, who have not accepted Jesus as king.[3][4] At first sight the destruction of the fig tree does not seem to fit Jesus' behaviour elsewhere, but the miracle stories are directed against property rather than people, and form a "prophetic act of judgement".[6] In Why I Am Not a Christian, Bertrand Russell used the tale to dispute the greatness of Jesus.[7]

Gospel of Mark, 11:12–25

The majority of scholars consider Mark’s narrative of the fig tree to be a sandwich or intercalated narrative.[8] Mark uses the cursing of the barren fig tree to bracket and comment on his story of the Jewish temple: Jesus and his disciples are on their way to Jerusalem when Jesus curses a fig tree because it bears no fruit; in Jerusalem he drives the money-changers from the temple; and the next morning the disciples find that the fig tree has withered and died, with the implied message that the temple is cursed and will wither because, like the fig tree, it failed to produce the fruit of righteousness.[9] The episode concludes with a discourse on the power of prayer, leading some scholars to interpret this, rather than the eschatological aspect, as its primary motif,[10] but at verse 28 Mark has Jesus again use the image of the fig tree to make plain that Jerusalem will fall and the Jewish nation be brought to an end before their generation passes away.[11]

Gospel of Matthew, 21:18–22

Matthew compresses Mark's divided account into a single story.[12] Here the fig tree withers immediately after the curse is pronounced, driving the narrative forward to Jesus' encounter with the Jewish priesthood and his curse against them and the temple.[13] Jesus responds to the disciples' expressions of wonder with a brief discourse on faith and prayer, and while this makes it less clear that the dead fig tree is related to the fate of the temple, in Matthew 24:32–35 the author follows Mark closely in presenting the "lesson" (in Greek, parabole) of the budding tree as a sign of the certain coming of the Son of Man.[14][15]

Gospel of Luke, 13:6–9

Luke replaces the miracle with a parable, probably originating from the same body of tradition that lies behind Mark.[16] Jesus and the disciples are traveling to Jerusalem when they hear of the deaths of Galileans, and Jesus gives the events a prophetic interpretation through a parable: a man planted a fig tree expecting it to bear fruit, but despite his visits it remained barren; the owner's patience wore thin, but the gardener pleaded for a little more time; the owner agrees, but the question of whether the tree would bear fruit, i.e. acts that manifest the Kingdom of God, is left hanging.[17] Luke has Jesus end his story with a warning that if the followers do not repent they will perish.[16]

Parallels in other texts

A very different story appears in Infancy Gospel of Thomas, but has a similar quotation from Jesus: "…behold, now also thou shalt be withered like a tree, and shalt not bear leaves, neither root, nor fruit." (III:2).[18]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cursing the fig tree. |

- Figs in the Bible

- Life of Jesus in the New Testament

- Parable of the budding fig tree

- Parable of the barren fig tree

References

Citations

- Dumbrell 2001, p. 67.

- Edwards 2002, p. 338.

- Burkett 2002, p. 170-171.

- Dumbrell 2001, p. 175.

- Burkett 2002, p. 143.

- Keener 1999, p. 503-504.

- Jesus Behaving Badly: The Puzzling Paradoxes of the Man from Galilee, Mark L. Strauss, p. 64.

- Frank Kermode, The Genesis of Secrecy: On the Interpretation of Narrative (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1979), pp. 128–34; James R. Edwards, “Markan Sandwiches: The Significance of Interpolations in Markan Narratives,” Novum Testamentum 31 no. 3 (1989): 193–216; Tom Shepherd, “The Narrative Function of Markan Intercalation,” New Testament Studies 41 (1995): 522–40; James L. Resseguie, "A Glossary of New Testament Narrative Criticism with Illustrations," in Religions, 10 (3: 217), 28; David Rhoads, Joanna Dewey, and Donald Michie, Mark as Story: An Introduction to the Narrative of a Gospel, 3rd ed. (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2012), 51–52.

- Reddish 2011, p. 79-80.

- Kinman 1995, p. 123-124.

- Dumbrell 2001, p. 202.

- Keener 1999, p. 503.

- Perkins 2009, p. 166-167.

- Kinman 1995, p. 124.

- Getty-Sullivan 2007, p. 74-75.

- Getty-Sullivan 2007, p. 126.

- Getty-Sullivan 2007, p. 127.

- James, M. R., 1924, The Apocryphal New Testament, Oxford: Clarendon Press

Bibliography

- Burkett, Delbert Royce (2002). An introduction to the New Testament and the origins of Christianity. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521007207.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Carroll, John T. (2012). Luke: A Commentary. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664221065.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cousland, J.R.C. (2017). Holy Terror: Jesus in the Infancy Gospel of Thomas. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9780567668189.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dumbrell, W.J. (2001). The Search for Order: Biblical Eschatology in Focus. Wipf and Stock. ISBN 9781579107963.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Edwards, James R. (2002). The Gospel According to Mark. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780851117782.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Getty-Sullivan, Mary Ann (2007). Parables of the Kingdom: Jesus and the Use of Parables in the Synoptic Tradition. Liturgical Press. ISBN 9780814629932.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Keener, Craig (1999). A Commentary on the Gospel of Matthew. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802838216.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kinman, Brent (1995). Jesus' entry into Jerusalem: in the context of Lukan theology and the politics of his day. Brill. ISBN 9004103309.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Perkins, Pheme (2009). Introduction to the Synoptic Gospels. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802865533.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Reddish, Mitchell G. (2011). An Introduction to The Gospels. Abingdon Press. ISBN 9781426750083.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)