Epithelium

Epithelium (/ˌɛpɪˈθiːliəm/)[1] is one of the four basic types of animal tissue, along with connective tissue, muscle tissue and nervous tissue. Epithelial tissues line the outer surfaces of organs and blood vessels throughout the body, as well as the inner surfaces of cavities in many internal organs. An example is the epidermis, the outermost layer of the skin.

| Epithelium | |

|---|---|

Types of epithelium | |

| Pronunciation | epi- + thele + -ium |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D004848 |

| TH | H2.00.02.0.00002 |

| FMA | 9639 |

| Anatomical terms of microanatomy | |

| This article is one of a series on |

| Epithelia |

|---|

| Squamous epithelial cell |

| Columnar epithelial cell |

| Cuboidal epithelial cell |

| Specialised epithelia |

|

| Other |

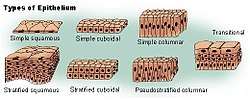

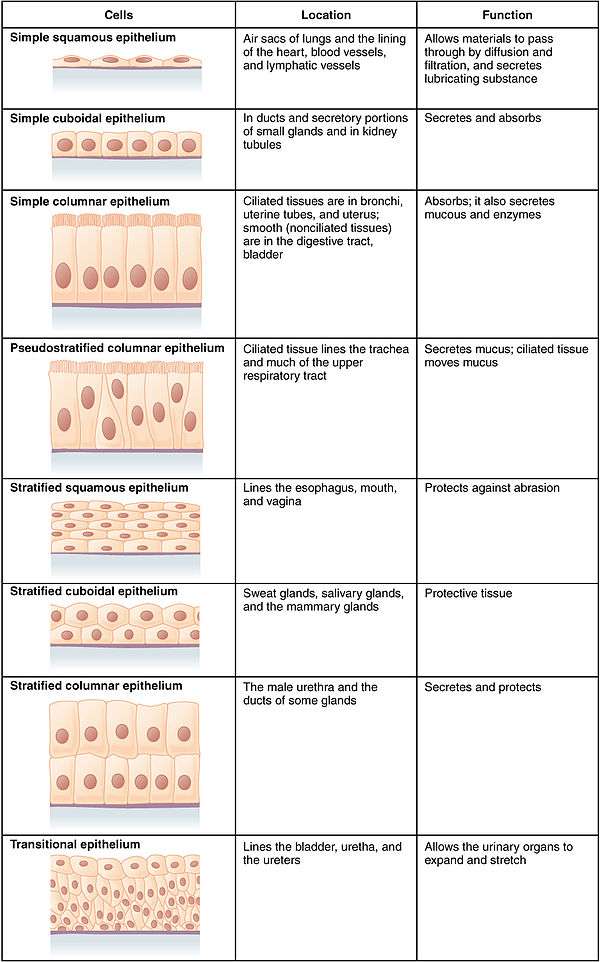

There are three principal shapes of epithelial cell: squamous, columnar, and cuboidal. These can be arranged in a single layer of cells as simple epithelium, either squamous, columnar, or cuboidal, or in layers of two or more cells deep as stratified (layered), or compound, either squamous, columnar or cuboidal. In some tissues, a layer of columnar cells may appear to be stratified due to the placement of the nuclei. This sort of tissue is called a pseudostratified. All glands are made up of epithelial cells. Functions of epithelial cells include secretion, selective absorption, protection, transcellular transport, and sensing.

Epithelial layers contain no blood vessels, so they must receive nourishment via diffusion of substances from the underlying connective tissue, through the basement membrane.[2][3] Cell junctions are well employed in epithelial tissues.

Classification

In general, epithelial tissues are classified by the number of their layers and by the shape and function of the cells.[2][4][5]

The three principal shapes associated with epithelial cells are squamous, cuboidal, and columnar.

- Squamous epithelium has cells that are wider than their height (flat and scale-like). This is found as the lining of the mouth, oesophagus, and including blood vessels and in the alveoli of the lungs.

- Cuboidal epithelium has cells whose height and width are approximately the same (cube shaped).

- Columnar epithelium has cells taller than they are wide (column-shaped). Columnar epithelium can be further classified into ciliated columnar epithelium and glandular columnar epithelium.

By layer, epithelium is classed as either simple epithelium, only one cell thick (unilayered), or stratified epithelium having two or more cells in thickness, or multi-layered – as stratified squamous epithelium, stratified cuboidal epithelium, and stratified columnar epithelium,[6][7] and both types of layering can be made up of any of the cell shapes.[4] However, when taller simple columnar epithelial cells are viewed in cross section showing several nuclei appearing at different heights, they can be confused with stratified epithelia. This kind of epithelium is therefore described as pseudostratified columnar epithelium.[8]

Transitional epithelium has cells that can change from squamous to cuboidal, depending on the amount of tension on the epithelium.[9]

Simple epithelium

Simple epithelium is a single layer of cells with every cell in direct contact with the basement membrane that separates it from the underlying connective tissue. In general, it is found where absorption and filtration occur. The thinness of the epithelial barrier facilitates these processes.[4]

In general, simple epithelial tissues are classified by the shape of their cells. The four major classes of simple epithelium are (1) simple squamous, (2) simple cuboidal, (3) simple columnar, and (4) pseudostratified.[4]

- (1) Simple squamous: Squamous epithelial cells appear scale-like, flattened, or rounded (e.g., walls of capillaries, linings of the pericardial, pleural, and peritoneal cavities, linings of the alveoli of the lungs).

- (2) Simple cuboidal: These cells may have secretory, absorptive, or excretory functions. Examples include small collecting ducts of the kidney, pancreas, and salivary gland.

- (3) Simple columnar: Cells can be secretory, absorptive, or excretory. Simple columnar epithelium can be ciliated or non-ciliated; ciliated columnar is found in the female reproductive tract and uterus. Non-ciliated epithelium can also possess microvilli. Some tissues contain goblet cells and are referred to as simple glandular columnar epithelium. These secrete mucus and are found in the stomach, colon, and rectum.

- (4) Pseudostratified columnar epithelium: These can be ciliated or non-ciliated. The ciliated type is also called respiratory epithelium since it is almost exclusively confined to the larger respiratory airways of the nasal cavity, trachea, and bronchi.

Stratified epithelium

Stratified epithelium differs from simple epithelium in that it is multilayered. It is therefore found where body linings have to withstand mechanical or chemical insult such that layers can be abraded and lost without exposing subepithelial layers. Cells flatten as the layers become more apical, though in their most basal layers, the cells can be squamous, cuboidal, or columnar.[10]

Stratified epithelia (of columnar, cuboidal, or squamous type) can have the following specializations:[10]

| Specialization | Description |

|---|---|

| Keratinized | In this particular case, the most apical layers (exterior) of cells are dead and lose their nucleus and cytoplasm, instead contain a tough, resistant protein called keratin. This specialization makes the epithelium somewhat water-resistant, so is found in the mammalian skin. The lining of the esophagus is an example of a non-keratinized or "moist" stratified epithelium.[10] |

| Parakeratinized | In this case, the most apical layers of cells are filled with keratin, but they still retain their nuclei. These nuclei are pyknotic, meaning that they are highly condensed. Parakeratinized epithelium is sometimes found in the oral mucosa and in the upper regions of the esophagus.[11] |

| Transitional | Transitional epithelia are found in tissues that stretch, and it can appear to be stratified cuboidal when the tissue is relaxed, or stratified squamous when the organ is distended and the tissue stretches. It is sometimes called urothelium since it is almost exclusively found in the bladder, ureters and urethra.[10] |

Cell types

The basic cell types are squamous, cuboidal, and columnar, classed by their shape.

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Squamous | Squamous cells have the appearance of thin, flat plates that can look polygonal when viewed from above.[12] Their name comes from squāma, Latin for "scale" – as on fish or snake skin. The cells fit closely together in tissues, providing a smooth, low-friction surface over which fluids can move easily. The shape of the nucleus usually corresponds to the cell form and helps to identify the type of epithelium. Squamous cells tend to have horizontally flattened, nearly oval-shaped nuclei because of the thin, flattened form of the cell. Squamous epithelium is found lining surfaces such as skin or alveoli in the lung, enabling simple passive diffusion as also found in the alveolar epithelium in the lungs. Specialized squamous epithelium also forms the lining of cavities such as in blood vessels (as endothelium), in the pericardium (as mesothelium), and in other body cavities. |

| Cuboidal | Cuboidal epithelial cells have a cube-like shape and appear square in cross-section. The cell nucleus is large, spherical and is in the center of the cell. Cuboidal epithelium is commonly found in secretive tissue such as the exocrine glands, or in absorptive tissue such as the pancreas, the lining of the kidney tubules as well as in the ducts of the glands. The germinal epithelium that covers the female ovary, and the germinal epithelium that lines the walls of the seminferous tubules in the testes are also of the cuboidal type. Cuboidal cells provide protection and may be active in pumping material in or out of the lumen, or passive depending on their location and specialisation. Simple cuboidal epithelium commonly differentiates to form the secretory and duct portions of glands.[13] Stratified cuboidal epithelium protects areas such as the ducts of sweat glands,[14] mammary glands, and salivary glands. |

| Columnar | Columnar epithelial cells are elongated and column-shaped and have a height of at least four times their width. Their nuclei are elongated and are usually located near the base of the cells. Columnar epithelium forms the lining of the stomach and intestines. The cells here may possess microvilli for maximizing the surface area for absorption, and these microvilli may form a brush border. Other cells may be ciliated to move mucus in the function of mucociliary clearance. Other ciliated cells are found in the fallopian tubes, the uterus and central canal of the spinal cord. Some columnar cells are specialized for sensory reception such as in the nose, ears and the taste buds. Hair cells in the inner ears have stereocilia which are similar to microvilli. Goblet cells are modified columnar cells and are found between the columnar epithelial cells of the duodenum. They secrete mucus, which acts as a lubricant. Single-layered non-ciliated columnar epithelium tends to indicate an absorptive function. Stratified columnar epithelium is rare but is found in lobar ducts in the salivary glands, the eye, the pharynx, and sex organs. This consists of a layer of cells resting on at least one other layer of epithelial cells, which can be squamous, cuboidal, or columnar. |

| Pseudostratified | These are simple columnar epithelial cells whose nuclei appear at different heights, giving the misleading (hence "pseudo") impression that the epithelium is stratified when the cells are viewed in cross section. Ciliated pseudostratified epithelial cells have cilia. Cilia are capable of energy-dependent pulsatile beating in a certain direction through interaction of cytoskeletal microtubules and connecting structural proteins and enzymes. In the respiratory tract, the wafting effect produced causes mucus secreted locally by the goblet cells (to lubricate and to trap pathogens and particles) to flow in that direction (typically out of the body). Ciliated epithelium is found in the airways (nose, bronchi), but is also found in the uterus and Fallopian tubes, where the cilia propel the ovum to the uterus. |

Structure

Epithelial tissue is scutoid shaped, tightly packed and form a continuous sheet. It has almost no intercellular spaces. All epithelia is usually separated from underlying tissues by an extracellular fibrous basement membrane. The lining of the mouth, lung alveoli and kidney tubules are all made of epithelial tissue. The lining of the blood and lymphatic vessels are of a specialised form of epithelium called endothelium.

Location

Epithelium lines both the outside (skin) and the inside cavities and lumina of bodies. The outermost layer of human skin is composed of dead stratified squamous, keratinized epithelial cells.[15]

Tissues that line the inside of the mouth, the esophagus, the vagina, and part of the rectum are composed of nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium. Other surfaces that separate body cavities from the outside environment are lined by simple squamous, columnar, or pseudostratified epithelial cells. Other epithelial cells line the insides of the lungs, the gastrointestinal tract, the reproductive and urinary tracts, and make up the exocrine and endocrine glands. The outer surface of the cornea is covered with fast-growing, easily regenerated epithelial cells. A specialised form of epithelium, endothelium, forms the inner lining of blood vessels and the heart, and is known as vascular endothelium, and lining lymphatic vessels as lymphatic endothelium. Another type, mesothelium, forms the walls of the pericardium, pleurae, and peritoneum.

In arthropods, the integument, or external "skin", consists of a single layer of epithelial ectoderm from which arises the cuticle,[16] an outer covering of chitin, the rigidity of which varies as per its chemical composition.

Basement membrane

Epithelial tissue rests on a basement membrane, which acts as a scaffolding on which epithelium can grow and regenerate after injuries.[17] Epithelial tissue has a nerve supply, but no blood supply and must be nourished by substances diffusing from the blood vessels in the underlying tissue. The basement membrane acts as a selectively permeable membrane that determines which substances will be able to enter the epithelium.[3]

Cell junctions

Cell junctions are especially abundant in epithelial tissues. They consist of protein complexes and provide contact between neighbouring cells, between a cell and the extracellular matrix, or they build up the paracellular barrier of epithelia and control the paracellular transport.[18]

Cell junctions are the contact points between plasma membrane and tissue cells. There are mainly 5 different types of cell junctions: tight junctions, adherens junctions, desmosomes, hemidesmosomes, and gap junctions. Tight junctions are a pair of trans-membrane protein fused on outer plasma membrane. Adherens junctions are a plaque (protein layer on the inside plasma membrane) which attaches both cells' microfilaments. Desmosomes attach to the microfilaments of cytoskeleton made up of keratin protein. Hemidesmosomes resemble desmosomes on a section. They are made up of the integrin (a transmembrane protein) instead of cadherin. They attach the epithelial cell to the basement membrane. Gap junctions connect the cytoplasm of two cells and are made up of proteins called connexins (six of which come together to make a connexion).

Development

Epithelial tissues are derived from all of the embryological germ layers:

- from ectoderm (e.g., the epidermis);

- from endoderm (e.g., the lining of the gastrointestinal tract);

- from mesoderm (e.g., the inner linings of body cavities).

However, it is important to note that pathologists do not consider endothelium and mesothelium (both derived from mesoderm) to be true epithelium. This is because such tissues present very different pathology. For that reason, pathologists label cancers in endothelium and mesothelium sarcomas, whereas true epithelial cancers are called carcinomas. Additionally, the filaments that support these mesoderm-derived tissues are very distinct. Outside of the field of pathology, it is generally accepted that the epithelium arises from all three germ layers.

Functions

Epithelial tissues have as their primary functions:

- to protect the tissues that lie beneath from radiation, desiccation, toxins, invasion by pathogens, and physical trauma

- the regulation and exchange of chemicals between the underlying tissues and a body cavity

- the secretion of hormones into the circulatory system, as well as the secretion of sweat, mucus, enzymes, and other products that are delivered by ducts[19]

- to provide sensation[20]

- Absorb water and digested food in the lining of digestive canal.

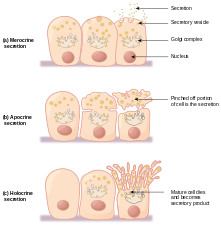

Glandular tissue

Glandular tissue is the type of epithelium that forms the glands from the infolding of epithelium and subsequent growth in the underlying connective tissue. There are two major classifications of glands: endocrine glands and exocrine glands:

- Endocrine glands secrete their product into the extracellular space where it is rapidly taken up by the circulatory system.

- Exocrine glands secrete their products into a duct that then delivers the product to the lumen of an organ or onto the free surface of the epithelium.

Sensing the extracellular environment

"Some epithelial cells are ciliated, especially in respiratory epithelium, and they commonly exist as a sheet of polarised cells forming a tube or tubule with cilia projecting into the lumen." Primary cilia on epithelial cells provide chemosensation, thermoception, and mechanosensation of the extracellular environment by playing "a sensory role mediating specific signalling cues, including soluble factors in the external cell environment, a secretory role in which a soluble protein is released to have an effect downstream of the fluid flow, and mediation of fluid flow if the cilia are motile."[21]

Clinical significance

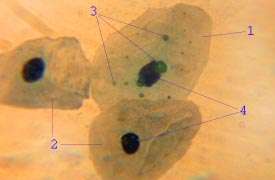

The slide shows at (1) an epithelial cell infected by Chlamydia pneumoniae; their inclusion bodies shown at (3); an uninfected cell shown at (2) and (4) showing the difference between an infected cell nucleus and an uninfected cell nucleus.

Epithelium grown in culture can be identified by examining its morphological characteristics. Epithelial cells tend to cluster together, and have a "characteristic tight pavement-like appearance". But this is not always the case, such as when the cells are derived from a tumor. In these cases, it is often necessary to use certain biochemical markers to make a positive identification. The intermediate filament proteins in the cytokeratin group are almost exclusively found in epithelial cells, so they are often used for this purpose.[22]

Cancers originating from the epithelium are classified as carcinomas. In contrast, sarcomas develop in connective tissue.[23]

When epithelial cells or tissues are damaged from cystic fibrosis, sweat glands are also damaged, causing a frosty coating of the skin.

Etymology and pronunciation

The word epithelium uses the Greek roots ἐπί (epi), "on" or "upon", and θηλή (thēlē), "nipple". Epithelium is so called because the name was originally used to describe the translucent covering of small "nipples" of tissue on the lip.[24] The word has both mass and count senses; the plural form is epithelia.

Additional images

Squamous epithelium 100x

Squamous epithelium 100x Human cheek cells (Nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium) 500x

Human cheek cells (Nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium) 500x Histology of female urethra showing transitional epithelium

Histology of female urethra showing transitional epithelium Histology of sweat gland showing stratified cuboidal epithelium

Histology of sweat gland showing stratified cuboidal epithelium

See also

- Dark cell

- Epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- Epithelial polarity

- Glycocalyx

- Inner and Outer enamel epithelium

- Iris pigment epithelium

- Neuroepithelial cell

- Retinal pigment epithelium

- Skin cancer

- Sulcular epithelium

References

- "epithelium Meaning in the Cambridge English Dictionary". dictionary.cambridge.org.

- Eurell, Jo Ann C.; et al., eds. (2006). Dellmann's textbook of veterinary histology. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-7817-4148-4.

- Freshney, 2002: p. 3

- Marieb, Elaine M. (1995). Human Anatomy and Physiology (3rd ed.). Benjamin/Cummings. pp. 103–104. ISBN 0-8053-4281-8.

- Platzer, Werner (2008). Color atlas of human anatomy: Locomotor system. Thieme. p. 8. ISBN 978-3-13-533306-9.

- van Lommel, 2002: p. 97

- van Lommel, 2002: p. 94

- Melfi, Rudy C.; Alley, Keith E., eds. (2000). Permar's oral embryology and microscopic anatomy: a textbook for students in dental hygiene. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-683-30644-6.

- Pratt, Rebecca. "Epithelial Cells". AnatomyOne. Amirsys, Inc. Archived from the original on 2012-12-19. Retrieved 2012-09-28.

- Jenkins, Gail W.; Tortora, Gerard J. (2013). Anatomy and Physiology from Science to Life (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. pp. 110–115. ISBN 978-1-118-12920-3.

- Ross, Michael H.; Pawlina, Wojciech (2015). Histology: A Text and Atlas: With Correlated Cell and Molecular Biology (7th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 528, 604. ISBN 978-1451187427.

- Kühnel, Wolfgang (2003). Color atlas of cytology, histology, and microscopic anatomy. Thieme. p. 102. ISBN 978-3-13-562404-4.

- Pratt, Rebecca. "Simple Cuboidal Epithelium". AnatomyOne. Amirsys, Inc. Retrieved 2012-09-28.

- Eroschenko, Victor P. (2008). "Integumentary System". DiFiore's Atlas of Histology with Functional Correlations. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 212–234. ISBN 9780781770576.

- Marieb, Elaine (2011). Anatomy & Physiology. Boston: Benjamin Cummings. p. 133. ISBN 0321616405.

- Kristensen, Niels P.; Georges, Chauvin (1 December 2003). "Integument". Lepidoptera, Moths and Butterflies: Morphology, Physiology, and Development : Teilband. Walter de Gruyter. p. 484. ISBN 978-3-11-016210-3. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

- McConnell, Thomas H. (2006). The nature of disease: pathology for the health professions. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-7817-5317-3.

- Alberts, Bruce (2002). Molecular biology of the cell (4. ed.). New York [u.a.]: Garland. p. 1067. ISBN 0-8153-4072-9.

- van Lommel, 2002: p. 91

- Alberts, Bruce (2002). Molecular biology of the cell (4 ed.). New York [u.a.]: Garland. p. 1267. ISBN 0-8153-4072-9.

- Adams, M.; Smith, U.M.; Logan, C.V.; Johnson, C.A. (2008). "Recent advances in the molecular pathology, cell biology and genetics of ciliopathies". Journal of Medical Genetics. 45 (5): 257–267. doi:10.1136/jmg.2007.054999. PMID 18178628.

- Freshney, 2002: p. 9

- "Types of cancer". Cancer Research UK. 28 October 2014. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- Blerkom, edited by Jonathan Van; Gregory, Linda (2004). Essential IVF : basic research and clinical applications. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-4020-7551-3.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

Bibliography

- Freshney, R.I. (2002). "Introduction". In Freshney, R. Ian; Freshney, Mary (eds.). Culture of epithelial cells. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-40121-6.

- van Lommel, Alfons T.L. (2002). From cells to organs: a histology textbook and atlas. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4020-7257-4.

Further reading

- Green H (September 2008). "The birth of therapy with cultured cells". BioEssays. 30 (9): 897–903. doi:10.1002/bies.20797. PMID 18693268.

- Kefalides, Nicholas A.; Borel, Jacques P., eds. (2005). Basement membranes: cell and molecular biology. Gulf Professional Publishing. ISBN 978-0-12-153356-4.

- Nagpal R; Patel A; Gibson MC (March 2008). "Epithelial topology". BioEssays. 30 (3): 260–6. doi:10.1002/bies.20722. PMID 18293365.

- Yamaguchi Y; Brenner M; Hearing VJ (September 2007). "The regulation of skin pigmentation" (Review). J. Biol. Chem. 282 (38): 27557–61. doi:10.1074/jbc.R700026200. PMID 17635904.

External links

| Look up epithelium in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Epithelium Photomicrographs

- Histology at KUMC epithel-epith02 Simple squamous epithelium of the glomerulus (kidney)

- Diagrams of simple squamous epithelium

- Histology at KUMC epithel-epith12 Stratified squamous epithelium of the vagina

- Histology at KUMC epithel-epith14 Stratified squamous epithelium of the skin (thin skin)

- Histology at KUMC epithel-epith15 Stratified squamous epithelium of the skin (thick skin)

- Stratified squamous epithelium of the esophagus

- Microanatomy Web Atlas