Cristóbal Acosta

Cristóvão da Costa or Cristóbal Acosta and Latinized as Christophorus Acosta Africanus (c. 1525 – c. 1594) was a Portuguese doctor and natural historian. He is considered a pioneer in the study of plants from the Orient, especially their use in pharmacology. Together with the apothecary Tomé Pires and the physician Garcia de Orta he was one of the pioneers of Indo-Portuguese medicine. He published a book on the medicinal plants of the orient titled Tractado de las drogas y medicinas de la Indias Orientales in 1578.

Cristóvão da Costa | |

|---|---|

_(cropped).png) | |

| Born | c. 1525 |

| Died | c. 1594 Huelva, Spain |

| Nationality | Portuguese |

| Occupation | Physician and naturalist |

Life

Cristóvão da Costa is believed to have been born somewhere in Africa, possibly in Tangier, Ceuta (both Portuguese cities at the time), or in Portuguese Cape Verde, since in his work he claims to be African (Christophorus Acosta Africanus), but the exact place and date of his birth remain unknown. He probably studied at Salamanca and first travelled to the East Indies in 1550 as a soldier. He took part in some campaigns against the native populace, and at one point was taken prisoner and held captive in Bengal. After returning to Portugal, he joined his former captain, Luís de Ataíde, who had been appointed viceroy of Portuguese India. He returned to Goa in 1568, the year Garcia de Orta died. He served as personal physician to the viceroy, and in 1569 was appointed physician to the royal hospital in Cochin,[1] where he had the opportunity of treating the king of Cochin. By 1571, he was noted as collecting botanical specimens from various parts of India. He returned to Portugal in 1572 after Ataíde's term ended. From 1576 to 1587 he served as surgeon and then physician in Burgos (Spain).[2]

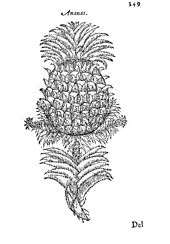

At Burgos in 1578 he published (in Spanish) his work Tractado de las drogas y medicinas de las Indias orientales ("Treatise of the drugs and medicines of the East Indies"). In this he says he was brought to India by his desire to find "in several regions and provinces learned and curious men from whom I could daily learn something new; and to see the diversity of plants God has created for human health". This work was translated into Italian in 1585 by Francesco Ziletti. Parts of this work were translated into Latin by Charles de l'Ecluse (Carolus Clusius), eventually to be included in his illustrated compendium Exoticorum libri decem.[2]

Costa's book is not considered wholly original, as it drew a great deal from the previously-published Colóquios dos Simples e Drogas da India by Garcia de Orta. With twenty three woodcuts, it soon became better known than Garcia's work (a rare work with only about ten copies in Europe).[3] The last entry was a treatise on the Asian elephant, probably the first to be published in Europe.[4] It was also among the first works to record words from the Basque language.[5]

Another work of note was Tractado de la yerbas, plantas, frutas y animales, but this treatise is now believed lost.

When his wife died, Acosta retired and went to live in a hermitage. He died in 1594 in Huelva, Spain.

See also

References

- Mathew, K.S. (1997). "The Portuguese and the study of medicinal plants in India in the sixteenth century" (PDF). Indian Journal of History of Science. 32 (4): 369–376. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-06-10.

- Guerra, Francisco (1970). "Acosta, Cristóbal". Dictionary of Scientific Biography. 1. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 47–48. ISBN 0-684-10114-9.

- Bhattacharyya, P.K. (1982). "Beginning of modern botany in India by Dutch in 16th-18th century (basic features and characteristics)" (PDF). Indian Journal of History of Science. 17 (2): 365–376.

- Ezquerra, Manuel Alvar (2006). "Léxico del Tractado de las drogas y medicinas de las Indias Orientales de Cristóbal Acosta". Verba. 33: 7–30.

- Zulaika Hernández, Josu M. (2014). "Cuatro voces vascas en el "Tractado de las drogas" (1578) de Acosta". 19: 311–325. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)