Craniofacial cleft

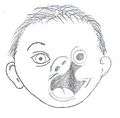

A facial cleft is an opening or gap in the face, or a malformation of a part of the face. Facial clefts is a collective term for all sorts of clefts. All structures like bone, soft tissue, skin etc. can be affected. Facial clefts are extremely rare congenital anomalies. There are many variations of a type of clefting and classifications are needed to describe and classify all types of clefting. Facial clefts hardly ever occur isolated; most of the time there is an overlap of adjacent facial clefts.[1]

Classifications

There are different classifications about facial clefts. Two of the most used classifications are the Tessier classification[2] and the Van der Meulen classification.[3] Tessier is based on the anatomical position of the cleft and Van der Meulen classification is based on the embryogenesis.

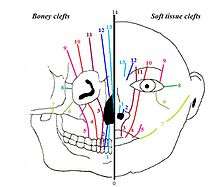

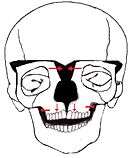

Tessier classification

In 1976 Paul Tessier published a classification on facial clefts based on the anatomical position of the clefts. The different types of Tessier clefts are numbered 0 to 14. These 15 different types of clefts can be put into 4 groups, based on their position:[4] midline clefts, paramedian clefts, orbital clefts and lateral clefts. The Tessier classification describes the clefts at soft tissue level as well as at bone level, because it appears that the soft tissue clefts can have a slightly different location on the face than the bony clefts.

Midline clefts

The midline clefts are Tessier number 0 ("median craniofacial dysplasia"), number 14 (frontonasal dysplasia), and number 30 ("lower midline facial cleft", also known as "median mandibular cleft"). These clefts bisect the face vertically through the midline. Tessier number 0 bisects the maxilla and the nose, Tessier number 14 comes between the nose and the frontal bone. The Tessier number 30 facial cleft is through the tongue, lower lip and mandible. The tongue may be absent, hypoplastic, bifid, or even duplicated.[5] People with this condition may be tongue-tied.[5]

Paramedian clefts

Tessier number 1, 2, 12 and 13 are the paramedian clefts. These clefts are quite similar to the midline clefts, but they are further away from the midline of the face. Tessier number 1 and 2 both come through the maxilla and the nose, in which Tessier number 2 is further from the midline (lateral) than number 1. Tessier number 12 is in extent of number 2, positioned between nose and frontal bone, while Tessier number 13 is in extent of number 1, also running between nose and forehead. Both 12 and 13 run between the midline and the orbit.

Orbital clefts

Tessier number 3, 4, 5, 9, 10 and 11 are orbital clefts. These clefts all have the involvement of the orbit. Tessier number 3, 4, and 5 are positioned through the maxilla and the orbital floor. Tessier number 9, 10 and 11 are positioned between the upper side of the orbit and the forehead or between the upper side of the orbit and the temple of the head. Like the other clefts, Tessier number 11 is in extent to number 3, number 10 is in extent to number 4 and number 9 is in extent to number 5.

Lateral clefts

The lateral clefts are the clefts which are positioned horizontally on the face. These are Tessier number 6, 7 and 8. Tessier number 6 runs from the orbit to the cheek bone. Tessier number 7 is positioned on the line between the corner of the mouth and the ear. A possible lateral cleft comes from the corner of the mouth towards the ear, which gives the impression that the mouth is bigger. It’s also possible that the cleft begins at the ear and runs towards the mouth. Tessier number 8 runs from the outer corner of the eye towards the ear. The combination of a Tessier number 6-7-8 is seen in the Treacher Collins syndrome. Tessier number 7 is more related to hemifacial microsomia and number 8 is more related to Goldenhar syndrome.

Van der Meulen classification

Van der Meulen classification divides different types of clefts based on where the development arrest occurs in the embryogenesis. A primary cleft can occur in an early stage of the development of the face (17 mm length of the embryo). The developments arrests can be divided in four different location groups: internasal, nasal, nasalmaxillar and maxillar. The maxillar location can be subdivided in median and lateral clefts.

Internasal dysplasia

Internasal dysplasia Nasal dysplasia

Nasal dysplasia Nasomaxillary dysplasia

Nasomaxillary dysplasia Maxillary dysplasia

Maxillary dysplasia

Internasal dysplasia

Internasal dysplasia is caused by a development arrest before the union of the both nasal halves. These clefts are characterized by a median cleft lip, a median notch of the cupid's bow or a duplication of the labial frenulum. Besides the median cleft lip, hypertelorism can be seen in these clefts. Also sometimes there can be an underdevelopment of the premaxilla.

Nasal dysplasia

Nasal dysplasia or nasoschisis is caused by a development arrest of the lateral side of the nose, resulting in a cleft in one of the nasal halves. The nasal septum and cavity can be involved, though this is rare. Nasoschisis is also characterized by hypertelorism.

Nasomaxillary dysplasia

Nasomaxillary dysplasia is caused by a development arrest at the junction of the lateral side of the nose and the maxilla, which results in a complete or non-complete cleft between the nose and the orbital floor (nasoocular cleft) or between the mouth, nose and the orbital floor (oronasal-ocular cleft). The development of the lip is normal.

Maxillary dysplasia

Maxillary dysplasia can manifest itself on two different locations in the maxilla: in the medial or the lateral part of the maxilla.

- Median maxillary dysplasia is caused by a development failure of the medial part of the maxillary ossification centers. This results in secondary clefting of the lip, philtrum and palate. Clefting from the maxilla to the orbital floor has also been reported.

- Lateral maxillary dysplasia is caused by a development failure of the lateral part of the maxillary ossification centers, which also results in secondary clefting of the lip and palate. Clefting of the lateral part of the lower eyelid is typical for lateral maxillary dysplasia.

Causes

It is possible that facial clefts are caused by a disorder in the migration of neural crest cells.[6]

Another theory is that facial clefts are caused by failure of the fusion process and failure of inwards growth of the mesoderm.

Other theories are that genetics play a part in the development of facial clefts[7] or that they are caused by amniotic bands.[8]

Genetics

Overview

Around one in 700 individuals are born with craniofacial clefts[9]. There are multiple genetic and environmental factors which contribute to craniofacial development. Within craniofacial disorders and abnormalities, orofacial clefts, and specifically cleft lip (CL) and cleft palate (CP) are the most common in humans[9]. Occurrences of CL/P are most often (around seventy percent of cases) isolated and nonsyndromic, meaning they are not associated with a syndrome or inherited genetic conditions[9][10]. Around thirty percent occur with other structural variances, and over 500 syndromes have been identified in which clefting is a principal feature[9][10]. Clefting can result from teratogens, an agent that disrupts embryo development such as, radiation, maternal infection, chemicals, or drugs[9][10]. Chromosomal abnormalities or mutations at single gene loci have also contributed to clefting development[9][10]. Genetic causes are linked with most craniofacial syndromes, and CL/P and other orofacial clefts are recognized as heterogeneous disorders, meaning there are multiple recognized causes[9][11]. Orofacial clefts have great phenotypic diversity, and their associated genetic environments have called for vast research and investigation.

Environmental Interaction

Craniofacial disorders have high variance in phenotypic expression, and researchers have suggested this variance could be due to interactions between the mutated/deviated genes and other genes, along with interactions with environmental factors[12][13]. Environmental causes have been found to contribute to craniofacial clefting, however, these are still influenced by and supported by genetic factors. Many studies, for example, have linked maternal smoking to increased CLP risk; however, the increased risk suggests that genes in metabolic pathways could still contribute to susceptibility or formation of CL/P[14].

Development and Inheritance

The craniofacial complex begins its progress in the fourth week of development, and results from neural crest cells migrating to form and fuse the facial primordia[9][10]. Failures or deviations in this process result in craniofacial clefts, either CL or CP[6]. The range of variation in phenotype aligns with ancestry[9][14]. Studies have found increased amounts of clefting in the relatives of patients with clefts, suggesting genetic factors are the underlying cause for CL/P[9]. Inheritance has a known and significant role in human craniofacial morphology. This is supported through cephalometric and anthropometric comparisons of family members including between triplets, twins, siblings, and parents and children[15].

Genetic Experimentation

Genetic factors of craniofacial clefting can be investigated and tracked through several methods including sequencing in humans, Genome-wide association studies (GWAs), fate mapping, expression analysis, and animal studies (knockout experiments or models with clefting from chemical mutagenesis)[16]. Twin studies and familial clustering have also revealed that facial structure and formation are genetically linked. Several genes have been associated with craniofacial disorders through experimentation, including sequencing Mendelian clefting syndromes[9]. Over 25 loci have been identified as potential influencers of craniofacial clefts across populations[12].

Linked Genes

The transforming growth factor (TGF) family has provided multiple candidate genes linked with craniofacial development and malformation[17][18][14][10]. TGF is involved in cell migration, differentiation, and proliferation, as well as regulating the extracellular matrix[17]. Another gene that has been flagged as causal for craniofacial disorders, including CL/P, is interferon regulatory factor 6 or, IRF6[9][14][19]. Mutations in IRF6 cause Van der Woude syndrome, the most common clefting syndrome[9]. Ventral anterior homeobox 1, VAX1, and noggin, NOG, were identified with genome-wide significance for contributing to CL/P[14]. Additionally, mutations in SPECC1L have recently been identified as influential to facial structure formation, and as causal for syndromic facial clefting[19][20]. Nonsyndromic CL/P has been associated with the transcription factor forkhead box protein E1 (FOXE1), as mutations have resulted in cases of CL/P in mice[10]. Other genes which have been found to interact with or contribute to craniofacial clefting include FGFRs, TWIST, MSXs, GREM1, TCOF1, PAXs, MAFB, ABCA4, and WNT allowing great cause for more research into the genetic basis for craniofacial disorders[11][18][12][13][14].

Prevention

Because the cause of facial clefts still is unclear, it is difficult to say what may prevent children being born with facial clefts. It seems that folic acid contributes to lowering the risk of a child being born with a facial cleft.[21]

Treatment

There is no single strategy for treatment of facial clefts, because of the large amount of variation in these clefts. Which kind of surgery is used depends on the type of clefting and which structures are involved. There is much discussion about the timing of reconstruction of bone and soft tissue. The problem with early reconstruction is the recurrence of the deformity due to the intrinsic restricted growth. This requires additional operations at a later age to make sure all parts of the face are in proportion.[22] A disadvantage of early bone reconstruction is the chance to damage the tooth germs, which are located in the maxilla, just under the orbit. The soft tissue reconstruction can be done at an early age, but only if the used skin flap can be used again during a second operation. The timing of the operation depends on the urgency of the underlying condition. If the operation is necessary to function properly, it should be done at early age. The best aesthetic result is achieved when the incisions are positioned in areas which attract the least attention (they cover up the scars). If, however, the function of a part of the face isn’t damaged, the operation depends on psychological factors and the facial area of reconstruction.

The treatment plan of a facial cleft is planned right after diagnosis. This plan includes every operation needed in the first 18 years of the patients life to reconstruct the face fully. In this plan, a difference is made between problems that need to be solved to improve the health of the patient (coloboma) and problems that need to be solved for a better cosmetic result (hypertelorism).

The treatment of the facial clefts can be divided in different areas of the face: the cranial anomalies, the orbital and eye anomalies, the nose anomalies, the midface anomalies and the mouth anomalies.

Treatment of the cranial anomalies

The most common cranial anomaly seen in combination with facial clefts is encephalocele.

Encephalocele

The treatment of encephalocele is based on surgery to repair the bony gap and provide adequate protection of the underlying brain. The question remains if the external brain tissue should be put back into the skull or if it is possible to cut off that piece of brain tissue, because its claimed that the external piece of brain tissue often isn’t functional,[23] with the exception of a basal encephalocele, in which the pituitary gland can be found in the mouth.

Treatment of orbital / eye anomalies

The most common orbital /eye anomalies seen in children with facial clefts are colobomas and vertical dystopia.

Coloboma

The coloboma which occurs often in facial clefts is a cleft in the lower or upper eyelid. This should be closed as soon as possible, to prevent drought of the eye and a consecutive loss of vision.[24]

Vertical orbital dystopia

Vertical orbital dystopia can occur in facial clefts when the orbital floor and/or the maxilla is involved in the cleft. Vertical orbital dystopia means that the eyes do not lay on the same horizontal line in the face (one eye is positioned lower than the other). The treatment is based on the reconstruction of this orbital floor, by either closing the boney cleft or reconstructing the orbital floor using a bone graft.[25]

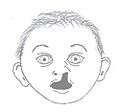

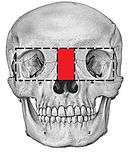

Hypertelorism

There are many types of operations which can be performed to treat a hypertelorism. 2 options are: box osteotomy and facial bipartition[26] (also referred to as a median fasciotomy). The goal of the box osteotomy is to bring the orbits closer together by removing a part of the bone between the orbits, to detach both orbits from the surrounding bone structures and move both orbits more to the centre of the face. The goal of the facial bipartition is not only to bring the orbits closer together, but also to create more space in the maxilla. This can be done by splitting the maxilla and the frontal bone, remove a triangular shaped piece of bone from the forehead and nasal bones and pulling the two pieces of forehead together. Not only will the hypertelorism be solved by pulling the frontal bone closer together, but because of this pulling, the space between the both parts of the maxilla will become wider.

Box Osteotomy

Facial Bipartition

Treatment of nose anomalies

The nose anomalies found in facial clefts vary. The main goal of the treatment is to reconstruct the nose to get a functional and esthetic acceptable result. A few possible treatment options are to reconstruct the nose with a forehead flap or reconstruct the nasal dorsum with a bone graft, for example a rib graft. The nasal reconstruction with a forehead flap is based on the repositioning of a skin flap from the forehead to the nose. A possible downside of this reconstruction is that once you performed it at a younger age, you can’t lengthen the flap at a later stage. A second operation is often needed if the operation is done on early age, because the nose has a restricted growth in the cleft area. Repair of the ala (wing of the nose) often requires the inset of cartilage graft, commonly taken from the ear.[27]

Treatment of midface anomalies

The treatment of soft tissue parts of midface anomalies is often a reconstruction from a skin flap of the cheek. This skinflap can be used for other operations in the further, as it can be raised again and transposed again. In the treatment of midface anomalies there are generally more operations needed. Bone tissue reconstruction of the midface often occurs later than the soft tissue reconstruction. The most common method to reconstruct the midface is by using the fracture/ incision lines described by René Le Fort. When the cleft involves the maxilla, it is likely that the impaired growth will result in a smaller maxillary bone in all 3 dimensions (height, projection, width).

Treatment of mouth anomalies

There are several options for treatment of mouth anomalies like Tessier cleft number 2-3-7 . These clefts are also seen in various syndromes like Treacher Collins syndrome and hemifacial microsomia, which makes the treatment much more complicated. In this case, treatment of mouth anomalies is a part of the treatment of the syndrome.

See also

Related articles

- Ectrodactyly–ectodermal dysplasia–cleft syndrome

- Cleft hand

- Cleft lip and palate

Syndromes

References

- Moore, MH (1996). "Rare craniofacial clefts". The Journal of Craniofacial Surgery. 7 (6): 408–11. doi:10.1097/00001665-199611000-00003. PMID 10332258.

- Tessier, P (1976). "Anatomical classification of facial, cranio-facial and latero-facial clefts". Journal of Maxillofacial Surgery. 4 (2): 69–92. doi:10.1016/S0301-0503(76)80013-6. PMID 820824.

- Van der Meulen, JCH; et al. (1989). "Facial Clefts". World J. Surg. 13 (4): 373–383. doi:10.1007/BF01660750. PMID 2773497. S2CID 41780755.

- Fearon, JA et al. "Rare Craniofacial Clefts: A surgical Classification", J Craniofac Surg. 2008 Jan;19(1):110-2,Fearon, JA (2008). "Rare craniofacial clefts: a surgical classification". The Journal of Craniofacial Surgery. 19 (1): 110–2. doi:10.1097/SCS.0b013e31815ca1ba. PMID 18216674. S2CID 1674500.

- Bhattacharyya, NC; Kalita, K; Gogoi, M; Deuri, PK (2012). "Tessier 30 facial cleft". Journal of Indian Association of Pediatric Surgeons. 17 (2): 75–7. doi:10.4103/0971-9261.93970. PMC 3326828. PMID 22529554.

- Hunt, Jeremy A.; Hobar, P. Craig (2003). "Common Craniofacial Anomalies: Facial Clefts and Encephaloceles". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 112 (2): 606–616. doi:10.1097/01.PRS.0000070971.95846.9C. PMID 12900623.

- Fogh-Andersen, P. (1967). "Genetic and Non-Genetic Factors in the Etiology of Facial Clefts". Scandinavian Journal of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery and Hand Surgery. 1: 22–29. doi:10.3109/02844316709006555.

- Mayou, BJ; Fenton, OM (1981). "Oblique facial clefts caused by amniotic bands". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 68 (5): 675–81. doi:10.1097/00006534-198111000-00001. PMID 6794056.

- Leslie, E.J., and Marazita, M.L. (2013). Genetics of Cleft Lip and Cleft Palate. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 163, 246–258.

- Yoon, A.J., Pham, B.N., and Dipple, K.M. (2016). Genetic Screening in Patients with Craniofacial Malformations. J Pediatr Genet 5, 220–224.

- Cohen, M.M. (2002). Malformations of the craniofacial region: evolutionary, embryonic, genetic, and clinical perspectives. Am. J. Med. Genet. 115, 245–268.

- Weinberg, Seth M., Robert Cornell, and Elizabeth J. Leslie. 2018. “Craniofacial Genetics: Where Have We Been and Where Are We Going?” PLoS Genetics 14 (6): e1007438. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1007438.

- Roosenboom, Jasmien, Greet Hens, Brooke C. Mattern, Mark D. Shriver, and Peter Claes. 2016. “Exploring the Underlying Genetics of Craniofacial Morphology through Various Sources of Knowledge.” Edited by Ilker ERCAN. BioMed Research International 2016 (December): 3054578. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/3054578.

- Dixon, M.J., Marazita, M.L., Beaty, T.H., and Murray, J.C. (2011). Cleft lip and palate: synthesizing genetic and environmental influences. Nat Rev Genet 12, 167–178.

- The Role of Genetics in Craniofacial Morphology and Growth | Annual Review of Anthropology.

- Facebase.org

- Genetic and Teratogenic Approaches To Craniofacial Development - D.L. Young, R.A. Schneider, D. Hu, J.A. Helms, 2000.

- Wilkie, A.O., and Morriss-Kay, G.M. (2001). Genetics of craniofacial development and malformation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2, 458–468.

- SPECC1L deficiency results in increased adherens junction stability and reduced cranial neural crest cell delamination. - PubMed - NCBI.

- Kruszka, P., Li, D., Harr, M.H., Wilson, N.R., Swarr, D., McCormick, E.M., Chiavacci, R.M., Li, M., Martinez, A.F., Hart, R.A., et al. (2015). Mutations in SPECC1L, encoding sperm antigen with calponin homology and coiled-coil domains 1-like, are found in some cases of autosomal dominant Opitz G/BBB syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 52, 104–110.

- Wilcox, A. J; Lie, R. T.; Solvoll, K.; Taylor, J.; McConnaughey, D R.; Abyholm, F.; Vindenes, H.; Vollset, S. E.; Drevon, C. A (2007). "Folic acid supplements and risk of facial clefts: national population based case-control study". BMJ. 334 (7591): 464. doi:10.1136/bmj.39079.618287.0B. PMC 1808175. PMID 17259187.

- Friede, Hans; Johanson, Bengt (1982). "Adolescent Facial Morphology of Early Bone-Grafted Cleft Lip and Palate Patients". Scandinavian Journal of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery and Hand Surgery. 16 (1): 41–53. doi:10.3109/02844318209006569. PMID 7051271.

- Kamerer, Donald B.; Caparosa, Ralph J. (1982). "Temporal Bone Encephalocele ??? Diagnosis and Treatment". The Laryngoscope. 92 (8): 878–882. doi:10.1288/00005537-198208000-00008. PMID 7098736.

- Patipa M et al., "Surgical management of congenital eyelid coloboma", Ophthalmic Surg. 1982 Mar;13(3):212-216 Patipa, M; Wilkins, RB; Guelzow, KW (1982). "Surgical management of congenital eyelid coloboma". Ophthalmic Surgery. 13 (3): 212–6. PMID 7088491.

- Tabrizi, Reza; Ozkan, Taha Birkan; Mohammadinejad, Cyrus; Minaee, Nasim (2010). "Orbital Floor Reconstruction". Journal of Craniofacial Surgery. 21 (4): 1142–1146. doi:10.1097/SCS.0b013e3181e57241. PMID 20613583. S2CID 44665427.

- Marchad D & Arnaud E, "Midface surgery from Tessier to distraction", Childs Nerv Syst. 1999 Nov;15(11-12):681-94, Marchac, D.; Arnaud, Eric (1999). "Midface surgery from Tessier to distraction". Child's Nervous System. 15 (11–12): 681–694. doi:10.1007/s003810050458. PMID 10603010. S2CID 27558780.

- Tardy, M. Eugene; Denneny, James; Fritsch, Michael H. (1985). "The Versatile Cartilage Autograft in Reconstruction of the Nose and Face". The Laryngoscope. 95 (5): 523–533. doi:10.1288/00005537-198505000-00003. PMID 3990484.