Coolnashinny

Coolnashinny (Irish: Cúl na Sionnach; The Corner of the Foxes)[1] is a townland in the civil parish of Kildallan in the barony of Tullyhunco, County Cavan, Ireland. It is also known as Croaghan (Irish: Cruachán, resembling hay). The townland was besieged during the Irish Rebellion of 1641.

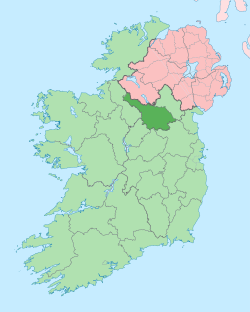

Geography

Coolnashinny is bounded on the north by the Drummully West and Mullaghmullan townlands, on the west by the Aghabane, Disert, Tullyhunco and Killygowan townlands, on the south by the Killytawny townland and on the east by the Cornaclea, Drummully East and Shancroaghan townlands. Its chief geographical features are Aghabane Lough,[2] Dumb Lough, the Croghan river, small streams and a wood. Coolnashinny is traversed by the regional R199, the local L5503 road, minor public roads and rural lanes. The townland covers 125 acres, including nine acres of water.[3]

Etymology

The 1256 Annals of Connacht identify the townland as Cruachain O Cubran; the Annals of Loch Cé for that year identify it as Cruachan O Cúbhrán. The Book of Magauran, in a poem composed around 1290, identifies it as Chruachna.[4][5] Other poems in that book spell the name as Cruachna Ó Cubran, Cruachain and Cruachain Ó Cubran. The Annals of the Four Masters spell it Cruachain Mec Tighernáin in 1412. The Annals of the Four Masters identify it in 1470 as Cruachain Ó Cuprain. The 1609 Plantation of Ulster map depicts the townland as Croghan,[6] and a 1610 grant spells it Croghin; however, a 1611 lease spells it Croghan. A 1629 inquisition spells it Collenasennagh and Craghan. Depositions in 1641 spell it Crohan, Croghan and Croaghan, and the 1652 Commonwealth Survey spells it Coolneshinagh.

History

From the early Middle Ages to the early 1600s, the townland belonged to the McKiernan Clan and was the site of the chief’s castle. Their lands were divided into units known as ballybetagh. According to a 1608 survey, a ballybetagh was named Ballycroughen and contained 16 polls (townlands) centered on Coolnashinny.[7]

The earliest surviving reference to the townland are in the Annals of Connacht and Loch Cé for 1256.[8] The McKiernan lands of Tullyhunco were on the border between the O'Rourke and O'Reilly clans, and the McKiernans were in conflict with both clans (who were trying to assert their authority).[9][10]

A reference to the townland is in poem I, stanza 16 (composed c. 1290) of the Book of Magauran. The poem refers to Maoilmheadha Mág Tighearnán, the daughter of Gíolla Íosa Mór Mág Tighearnán, chief of the McKiernan Clan from c. 1269 until his death in 1279. She was married to Brian Breaghach Mág Samhradháin, chief of the McGovern clan from 1272 until his death on 3 May 1294. Another reference in the Book of Magauran is poem XVIII, stanza 42 (composed c. 1325). This poem refers to Tomás Mág Samhradháin, chief of the McGovern Clan from c. 1325 until his death in 1340. He was the son of Brian Breaghach Mág Samhradháin and Maoilmheadha Mág Tighearnán. A third reference in the book is poem XXV, stanza 20 (composed c. 1339), about an attack on the McKiernan clan in Tullyhunco by Tomás Mág Samhradháin. The book's final reference is poem XXVI, stanza 13 (composed c. 1339), about a mustering of the three neighbouring clans at Cruachan: the McGoverns, the McKiernans and the Conmaicne Maigh Rein of Drumreilly parish.

According to the Annals of Ulster and the Four Masters, McKiernan chief Cú Connacht Mág Tighearnán was murdered in his castle at Coolnashinny in 1412 by the Maguire clan of Fermanagh. The McKiernan lands (Tullyhunco) were on the border between the O’Rourke and O’Reilly lands, and both clans were trying to claim overlordship of the McKiernans. The O’Rourkes and their allies, the O’Donnells, tried to install Domhnall O’Rourke (the O'Rourke chief from 1468 to 1476) in the McKiernan castle at Croaghan in 1470; the McKiernans successfully resisted the invasion at Ballyconnell, however, with aid from the O’Reillys and the English.

King James VI and I granted the Manor of Keylagh, which included four polls in Croghin in the Plantation of Ulster, to Scottish Groom of the Bedchamber John Achmootie on 27 June 1610; John's brother, Alexander, was granted the neighbouring Manor of Dromheada.[11] On 16 August of that year, John Aghmootie[12] sold his lands in Tullyhunco to James Craig. Craig leased, among other things, four polls of Croghan to McKiernan chief Brian Bán Mág Tighearnán on 1 May 1611. The polls included the modern townlands of Drumbinnis, Druminiskill, Killygowan and Mullaghmullan.[13] On 29 July 1611, Sir Arthur Chichester and others reported that John and Alexander had not taken possession of their lands.[14] Josias Bodley reported on 6 February 1613 that Craig was building on the lands.[15] According to a 2 November 1629 inquisition at Ballyconnell, Craghan's four polls contained 25 subdivisions: Dromenisklein, Toncruske, Mullaghmore, Dromisklin, Carmynebrine, Atticarheldan, Attibelimorris, Drombivise, Knockecurry, Killegowne, Mullaghnemullin, Tawnecaser, Lurge, Knockbrenan, Tawnemillagan, Tunebellrie, Aghemullen, Collenasennagh, Largleoure, Legge, Knockmaddeygarrie, Knockmaddidarragh, Knockmaister, Knockechoyle and Knocknegren.[16] Craig died in the siege of Croaghan Castle on 8 April 1642. His land was inherited by his brother, John Craig of Craig Castle, County Cavan and Craigston, County Leitrim, chief physician to James I and Charles I of England.[17]

Siege of Croaghan

Craig's castle at Croaghan was besieged by the McKiernans and their allies, the McGoverns and O'Reillys, at the beginning of the Irish Rebellion of 1641. Its inhabitants held out until 15 June 1642, when they surrendered and went to Drogheda. When Croaghan and Keelagh surrendered, McKiernan chief John Mág Tighearnán was a signatory of the surrender agreement.[18] The 1641 Depositions also include other references to the siege under the names Croghan and Croaghan- (Deposition of Ambrose Bedell 26/10/1642 MS 833 105r; Deposition of Patrick Bell 9/11/1642 MS 833 107r; Deposition of Joane Woods (the younger) undated MS 832 166v: Deposition of Ellenor Reinolds undated MS 832 167r; Deposition of Henry Baxter 21/6/1643 MS 833 217r; Deposition of George Creighton 15/4/1643 MS 833 227r; Deposition of Richard Parsons 24/2/1642 MS 833 275r; Deposition of John Seaman 30/5/1643 MS 833 263r).[19]

1650 to date

According to the 1652 Commonwealth Survey, the owner was Lady Craig. In the Hearth Money Rolls compiled on 29 September 1663[20] there were four Hearth Tax payers in Crochan- Thomas Hugh, Dame Mary Craig, Thomas Prick and Alexander Trotters and one in Killifonnie- Shane Baye. All had one hearth apart from Dame Mary who had two, indicating a larger house than the rest. Lord John Carmichael (1710–1787), the 4th Earl of Hyndford of Castle Craig, County Cavan, inherited the lands from the Craig estate. Carmichael sold the lands to the Farnham Estate of Cavan in 1758, and the estate papers are archived in the National Library of Ireland.[21]

A marriage settlement by Margery Ells dated 15 September 1762 refers to her lands in Crochan.[22] The 1790 Cavan Carvaghs list spells the townland "Coolnesynagh",[23] and the 1825 Tithe Applotment Books list four tithe-payers in the townland.[24]

The Coolnashinny Valuation Office books are available for 1838.[25][26]

The Cavan Archives Service has a conveyance dated 4 October 1842 (reference number P017/0052) of the "Coolnashinny" in County Cavan – rented from Henry Maxwell, 7th Baron Farnham – from James Berry to his son John.[27] Griffith's Valuation of 1857 lists fifteen landholders in the townland.[28] The landlord of most of Coolnashinny during the 19th century was Richard Carson.[28] Folklore related to Coolnashinny from the 1937 Dúchas collection is available online.[29]

Population

| Year | Population | Males | Females | Total houses | Uninhabited |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1841 | 30 | 14 | 16 | 7 | 2 |

| 1851 | 47 | 37 | 10 | 7 | 3 |

| 1861 | 64 | 43 | 21 | 7 | 1 |

| 1871 | 28 | 10 | 18 | 6 | 1 |

| 1881 | 21 | 14 | 7 | 7 | 2 |

| 1891 | 24 | 7 | 17 | 4 | 0 |

The 1901 census of Ireland reported twelve families in the townland.[30] In the 1911 census, the number of families had fallen to five.[31]

Artifacts

The Architectural Survey of County Cavan describes a bawn,[32][33] which may have contained a mausoleum. George Carson was the Presbyterian minister at Coolnashinny from 1735 to 1780, and died on 10 January 1782.[34] The Croaghan Presbyterian Church and graveyard was built in 1742.[35][36][37]

Roman Catholic Bernard Cusack ran the Crohan Hedge School, a private school in a stable, for 40 boys and 27 girls in 1826. Fifty-two of his students were Roman Catholic, and 15 belonged to the Church of Ireland. The headmaster's salary was £10 per year.[38] Croaghan House and Croaghan Bridge are other historic sites.[39] The National Museum of Ireland has a dirk 24.2 centimetres (10 in) long and 5.4 centimetres (2 in) wide, with a trapezoidal butt and two rivet holes, which was found at Coolnashinny.[40]

References

- "Placenames Database of Ireland – Coolnashinny". Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- "documents/994-guide-to-coarse-angling-in-the-erne-and-south-donegal/file". fisheriesireland.ie. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- "IreAtlas". Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- L. McKenna (1947), The Book of Magauran

- "Image: 1609-hi_Keylagh.jpg, (815 × 1286 px)". cavantownlands.com. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- page 211

- "Annals of Loch Cé". Archived from the original on 1 January 2019. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- C. Parker, "Two minor septs of late medieval Breifne", in Breifne Journal, Vol. VIII, No. 31 (1995), pp. 566–586

- M.V. Duignan (1934), "The Uí Briúin Bréifni genealogies", pp. 90–137, in JRSAI Vol. 4, No. 1, 30 June 1934.

- Calendar of the Patent Rolls of the Chancery of Ireland. - (Dublin 1800.) (angl.) 372 S. 1800. p. 166. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- Inquisitionum in Officio Rotulorum Cancellariae Hiberniae Asservatarum Repertorium. command of his majesty King George IV. In pursuance of an address of the house of Commons of Great Britain (an Ireland). 1829. p. 2. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- "Calendar of the Carew manuscripts, preserved in the archi-episcopal library at Lambeth ." archive.org. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- Inquisitionum in Officio Rotulorum Cancellariae Hiberniae Asservatarum Repertorium. command of his majesty King George IV. In pursuance of an address of the house of Commons of Great Britain (an Ireland). 1829. pp. 5–6. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- Gilbert, John Thomas; Irish Archaeological and Celtic Society, Dublin (1 January 1879). "A contemporary history of affairs in Ireland, from 1641 to 1652. Now for the first time published, with an appendix of original letters and documents. Edited by John T. Gilbert". Dublin For the Irish Archaeological and Centic Society – via Internet Archive.

- The Hearth Money Rolls for the Baronies of Tullyhunco and Tullyhaw, County Cavan, edited by Rev. Francis J. McKiernan, in Breifne Journal. Vol. I, No. 3 (1960), pp. 247-263

- Peter Kenny (12 September 2005). "Leabharlann Náisiúnta na hÉireann" (PDF). Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- "Memorial extract — Registry of Deeds Index Project". Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- "The Carvaghs" (PDF). 7 October 2011. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- "The Tithe Applotment Books, 1823–37". titheapplotmentbooks.nationalarchives.ie. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- "Griffith's Valuation". askaboutireland.ie. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- "Irish Folklore Commission". Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- "National Archives: Census of Ireland 1901". Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- "National Archives: Census of Ireland 1911". Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- Davies, O. (1948). "The castles of county Cavan, Part 2". Ulster Journal of Archaeology issue 11, pp. 80-126.

- Wilsdon, B. (2010) Plantation Castles on the Erne. Dublin: The History Press, pp. 186-91.

- George Carson, A discourse, delivered at Croghan on January to the United Companies of Tullahunco and Balliconnel Volunteers (Dublin, 1780).

- "Main Record - County Cavan". Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- "History of the Congregations of the Presbyterian Church in Ireland". Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- "Buildings of Ireland". Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- No. 1594, acquired in 1937.