Consulate General of the United States, Shenyang

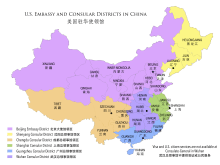

The Consulate General of the United States, Shenyang (simplified Chinese: 美国驻沈阳总领事馆; traditional Chinese: 美國駐瀋陽總領事館; pinyin: Měiguó zhù Shěnyáng Zǒnglǐngshìguǎn) is one of seven American diplomatic and consular posts in the People's Republic of China.[1] It is located in Heping District, Shenyang, Liaoning.[2]

History

The U.S. Consulate in Shenyang was opened in 1904.[3] It was originally housed in two abandoned Chinese temples, “Temples ‘Yi Kung Ssu’ and ‘Scwang Chen Ssu’ located outside the Little West Commerce Gate.” Sometime before 1924, the Consulate moved to No. 1 Wu Wei Lu, a building which used to house the Russian Consulate. At that time, the United States had several other Consulates in Northeast China, including in Harbin and Dalian. These appear to have been closed by World War II. The Shenyang Consulate was able to continue operations for most of the war but closed in 1949 after the new Chinese Communist Party authorities had imprisoned the remaining consulate staff in their offices for almost a year before expelling them. In 1984, five years after the United States recognized formally established diplomatic relations with the government in Beijing, the Consulate reopened; today it plays a key part in the management of the close relationship the United States has with northeast China.

Adventure in the 1930s and 40s

In the early part of the 20th century, northeast China underwent enormous economic development and population growth. Due primarily to the advent of the railroads developed by Japanese and Russian interests and the rapid in-migration of settlers from Shandong Province and the Korean Peninsula, Shenyang (known then as “Mukden” to most Americans), Harbin, Dalian, Changchun, and other places grew from almost nothing into major cities. For the Americans who were stationed there in the 1930s and 1940s, however, Shenyang increasingly resembled a frontier outpost marked by adventure and danger. Consulate staff dealt with rampant lawlessness, violence, and the complex conflict in Manchuria between an increasingly large Japanese presence in the region, continuing Chinese resistance, and lingering Russian influence.

Several articles from the period reported failed attempts to bomb the American and British consulates, hijacking and attacks on trains, bank robberies, thefts, murders, kidnapping, and general mayhem, especially in 1932. One telling example: after “bandits” unsuccessfully attacked the American Consul General during a golf game, Americans began to carry guns whenever they went out to the golf course. According to the New York Times, the 700 mile long South Manchurian railway was raided an average of 42 times daily that year. And several months previously, a Japanese military patrol beat up an American official, Culver B. Chamberlain, while he was on his way to Harbin to become Consul there.

In 1934, the New York Times reported another rather minor but interesting episode: “A uniformed Japanese ran amok today at the United States Consulate, waving a bayonet.” Vice Consul Monroe B. Hall, according to the paper’s entertaining account, “hearing the noise, investigated, and found the intruder brandishing a bayonet.” Hall then “picked up a chair and engaged the man, shouting to Vice Consuls Gerald Warner and Andrew Eson for help.” Warner and Eson responded with “improvised weapons,” and the three of them fought the crazed soldier off. Complaints to the Japanese Consulate resulted in the soldier’s arrest a few hours later.

World War II

After Pearl Harbor, the Imperial Japanese forces took Vice Consul U. Alexis Johnson – later a senior official in the Kennedy and Johnson State Departments – and his staff prisoners. Released in 1942, Johnson and his staff returned to the United States, along with the American ambassador to Japan, Joseph Grew, and other civilians unlucky enough to have been captured by the Japanese in Asia. As Time magazine told the story, Johnson rushed down the gangplank of the neutral Swedish ship that had ferried him back to the United States, yelling at the assembled reporters, "I don't want to talk to newspapermen. I want to talk to my wife. I haven't seen her in three years." [vi] The magazine continued:

[Johnson] spied her in the crowd, walked up to her slowly, gravely.

"Hello," he said.

"Hello."

"How are you?"

"Fine. How are you?"

They didn't kiss; didn't even shake hands. They just looked at each other for a long while, then walked off and got in a cab.

Other Americans were less fortunate. As the war escalated, Shenyang became a holding ground for about 1,700 American and Allied POWs captured by the Japanese from places as far away as the Philippines. They were treated brutally – 700 of them died – and the healthiest survivors were barely able to walk when they were liberated in 1945 by Soviet Soldiers. The Shenyang municipal government is working with survivors groups to turn the restored POW camp into a museum.

The Cold War

After the end of World War II, the American diplomatic presence in northeast China resumed when Consul General O. Edmund Clubb reopened the Shenyang Consulate in 1945 only to face severe challenges during the final stages of the Chinese Civil War. In November 1948, with the American-supported Nationalist party in retreat in China, Communist Party forces captured Shenyang and, sparked by the onset of the Cold War, relations between China and the United States became increasingly tense. In 1948, the Communist authorities even went so far as to confine the American staff in Shenyang, now led by Consul General Angus I. Ward, to the grounds of the Consulate for nearly a year. By 1950, the United States had withdrawn all its diplomats from China.

Contact between the United States and China resumed again when Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger reached out to Beijing in 1972. Five years after America and the People’s Republic of China established diplomatic relations, the United States reopened its Consulate in Shenyang in 1984. One goal was to help open northeast China—with its enormous population of 91 million people and nearly 40 percent of China’s heavy industry—to American investment. There were geopolitical reasons, as well, relating to Chinese relations with the former Soviet Union and North Korea.

Modern Relations

In recent years, a series of American companies – including ITT, John Deere, Tyco, Boeing, Johnson Controls, Dell, Intel, Oracle, Citibank, Cessna and other major U.S. firms have all made significant investments in the region, particularly in the port city of Dalian. Major Chinese and U.S. universities have established strong exchange programs, and the U.S. Consulate has an active program of public outreach to local government, business, media, and cultural leaders, as well as to the general public.

As political cooperation continues to deepen between the United States and China, the Consulate has also played a vital role in meetings between American officials and their counterparts in northeast China, including military officers from the Pacific Command and Joint Chiefs of Staff, senior diplomats, and the U. S. Trade Representative. Because of its proximity to the border with North Korea, the Consulate has also worked with local Chinese counterparts on issues related to that country, including nuclear nonproliferation. Underscoring Shenyang’s growing importance, the Six Party Talks working group on nuclear disarmament met here in August 2007, and the Consulate provided the American delegation with important assistance.

Note

[i] A representative example: “Manchurian Raids Creating Terror.” New York Times 20 June 1933: pp. 5.

[ii] Associated Press. “American Golfers in Mukden Carry Guns to Resist Bandits.” New York Times 23 Sept., 1932: pp. 5.

[iii] “Manchuria Railway Raided 42 Times A Day.” New York Times 23 Aug., 1932: pp. 7

[iv] Abend, Hallet. “U.S. Consul Beaten by Japanese Patrol in Mukden Street.” New York Times 4 Jan., 1932: pp. 1.

[v] “U.S. Consuls in Mukden Drive Off Crazed Soldier.” New York Times 17 Jul., 1934: pp. 13.

[vi] “Back from the Jap.” Time Magazine 7 Sept., 1942. <http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,773536,00.html>

[vii] Song Lijun. “POWs’ painful memories of war.” China Daily. Clipping does not have a page number or date.

Consul Generals

Nancy Abella, 2019-present

Gregory May, 2017-2019

Scott Weinhold, 2013-2017[4]

Sean Stein, 2010–2013

Stephen Wickman, 2007-2010[5]

David Kornbluth, 2004-2007[6]

Mark Kennon, 2002-2004[7]

Angus Taylor Simmons, 1999-2002[8]

Gerard R. Pascua (including 1994)[9]

Mortin Holbrook III, 1990-1993

Carl Eugene "Gene" Dorris, 1987-1990

John A. "Jack" Froebe, 1986-1987

James Hall, 1984-1986

See also

References

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on May 1, 2013. Retrieved June 24, 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Security Message about Recent Protests at Emei Mountain ( July 8, 2014) Archived May 18, 2015, at the Wayback Machine" (). U.S. Consulate in Chengdu. Retrieved on May 17, 2015. "No. 52, 14th Wei Road, Heping District Shenyang 110003"

- U.S. Consulate History, U.S Embassy & Consulates in China

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on September 25, 2013. Retrieved October 8, 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Leadership Connect".

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on June 24, 2013. Retrieved June 24, 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Uncivil Military". The New Republic. March 2004.

- http://uscpublicdiplomacy.org/index.php/about/bio_detail/angus_taylor_simmons/

- Gerard R. Pascua