Chojnice

Chojnice ([xɔjˈɲit͡sɛ] (![]()

Chojnice | |

|---|---|

Historical town hall located at the Rynek (Market Square) | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

Chojnice  Chojnice | |

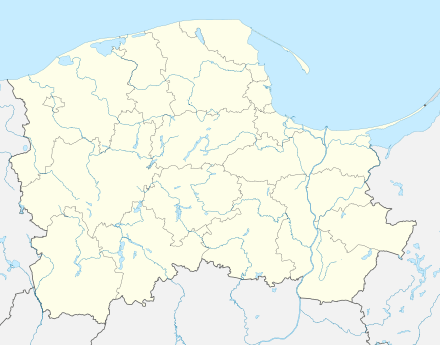

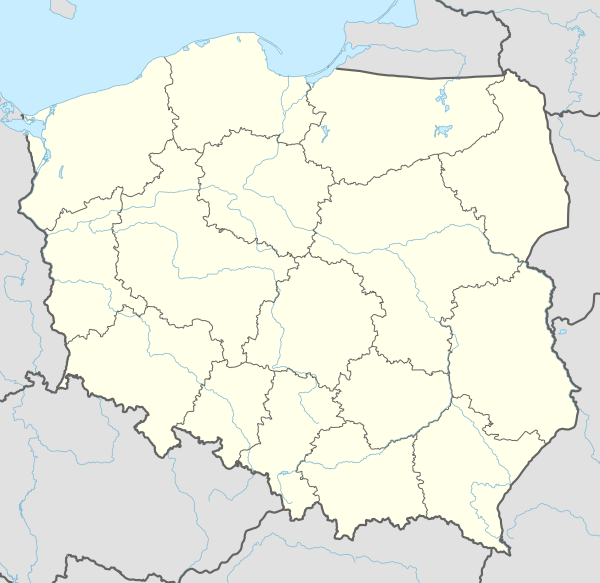

| Coordinates: 53°42′N 17°33′E | |

| Country | |

| Voivodeship | |

| County | Chojnice County |

| Gmina | Chojnice (urban gmina) |

| Established | 11th century |

| Town rights | 1325 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Arseniusz Finster |

| Area | |

| • Total | 21.05 km2 (8.13 sq mi) |

| Population (2011) | |

| • Total | 40,447[1] |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 89-600, 89-604, 89-620 |

| Area code(s) | +48 52 |

| Car plates | GCH |

| Website | http://www.miasto.chojnice.pl |

Chojnice has been a part of Pomeranian Voivodeship since 1999, as it was during the period 1945–1975; during the time span 1975–1998 the town belonged to Bydgoszcz Voivodeship.

History

Piast Poland

Chojnice was founded around 1205 (although the date is considered to be estimate)[2] in Gdańsk Pomerania (Pomeralia), a duchy ruled at the time by the Samborides, who had originally been appointed governors of the province by Bolesław III Wrymouth of Poland. Gdańsk Pomerania had been part of Poland since the 10th century, with few episodes of autonomy, yet under Swietopelk II, who came into power in 1217, it gained independence in 1227.[3] The duchy extended roughly from the river Vistula in the east, to the rivers Łeba or Grabowa in the west, and from the rivers Noteć and Brda in the south-west and south, to the Baltic Sea in the north. By 1282 the duchy had returned to Poland.

The town's name is Polish in origin and comes from the name of the river Chojnica (today named Jarcewska Struga) that was located near the town.[4] The name first appears in written documents in 1275.[5]

State of the Teutonic Order (1309–1466)

In 1309 the Teutonic Knights took over the town, and Chojnice became part of the State of the Teutonic Order.[6] Under Winrich von Kniprode the defensive capabilities and inner structures of the town were improved considerably. Around the middle of the 14th century the stone church of St. John was built. At the same time the Augustinians from the town of Stargard in Pomerania settled in the town; they opened their monastery in 1365. Textile production flourished, and between 1417-1436 Konitz became an important centre for textile production.

During the Polish–Lithuanian–Teutonic War, in 1410, the town was briefly occupied by Polish troops. In 1440 the town joined the Prussian Confederation, which opposed Teutonic rule,[7] however, it later left the organisation. In 1454 King Casimir IV Jagiellon re-incorporated the territory to the Kingdom of Poland, and the townspeople overthrew the pro-Teutonic town council in attempt to join Poland, however the council with the Teutonic Knights recaptured the town shortly after.[8] On 18 September 1454 the Polish army led by King Casimir IV Jagiellon lost the Battle of Chojnice. During the subsequent Thirteen Years' War there were attempts of the townspeople to resist the Teutonic Knights.[8] Shortly before the end of the war the troops of the Teutonic Order, led by Captain Kaspar Nostiz von Bethes, surrendered the town in 1466 to the Polish army led by Piotr Dunin, after a three-month siege,[9] as the last Teutonic-held town in Gdańsk Pomerania.[10]

Kingdom of Poland (1466–1772)

After the Second Peace of Thorn of 1466 the Teutonic Knights renounced any claims to Chojnice, and the town became again part of Poland.[11][10][9] It was located in the Człuchów County in the Pomeranian Voivodeship. Chojnice was an important center of cloth production in Poland.[12] Cloth production was the main branch of the local economy, and in 1570, clothiers constituted 36% of all craftsmen in the town.[12] To this day, one of the main streets in the town center is called Ulica Sukienników ("Clothiers' Street").[12]

In the 16th century the city council accepted the Protestant Reformation officially, and Protestants took over the parish church. The Roman Catholic priest Jan Siński died in the following turmoil. In 1555 King Sigismund II Augustus confirmed religious freedom for the city.[9] In 1616 the St. John's church was restored to the Catholics thanks to local parish priest Jan Doręgowski.[9] In 1620 the first Jesuits came into the town and began the Counter Reformation. In 1622 the Jesuits founded a school, which under the name Liceum Ogólnokształcące im. Filomatów Chojnickich w Chojnicach is today one of the oldest high schools in Poland.

In the year 1627 a fire destroyed parts of the town. During the Second Northern War (against Sweden, 1655–1660) the Battle of Chojnice (1656) was fought. The town suffered heavily from the siege, plundering and fire, especially in 1657. Cloth production declined as a result of the Swedish invasion, however, it soon revived.[13] In 1733–1744 the Baroque Jesuit Church of the Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin Mary was built.[14] A large fire destroyed the town again in 1742.[15]

Prussia (1772–1871) and German Empire (1871–1920)

After the first partition of Poland the town became part of the Kingdom of Prussia in 1772. The Prussians abolished the local government, which was restored in 1809.[9] The cloth industry collapsed.[13] The town was subject to anti-Polish policies, including Germanisation. At the local gymnasium, Polish was taught only two hours a week, in 1815-1820 and 1846-1912, and in 1889 the history of Polish literature was removed from the curriculum, while Polish history was not taught at all.[16] Probably in 1830 a secret organization of Polish students was established in the local school.[17] Some Polish students joined the Polish uprisings of 1830 and 1863 in the Russian Partition of Poland.[17] The organisation probably ceased to exist in the 1860s, because in 1870, a new youth philomath organization Mickiewicz was founded, named after the Polish national poet Adam Mickiewicz.[18] In 1901, due to the threat of repressions by the German authorities, the organization was dissolved to be reactivated after a few months.[18] Among local philomats were prominent Polish-Kashubian activists and writers Aleksander Majkowski, Florian Ceynowa and Jan Karnowski, future minister and senator in independent Poland Leon Janta-Połczyński, priest, historian and co-founder of the Toruń Scientific Society Stanisław Kujot, co-founder and president of the first Polish scientific society in the United States Dominik Szopiński, as well as priests and activists Bernard Łosiński and Konstantyn Krefft, who were later murdered by the Germans in Nazi concentration camps in 1940.[19] In 1911 the first Polish secret scout troop in the Prussian Partition of Poland was established in the town by Szczepan Łukowicz, who as a military officer later fought in defense of Poland during the Polish–Soviet War (1920) and the German Siege of Warsaw (1939), and was murdered by the Germans during World War II.[20]

In 1864 a telegraph connection to Szczecin (then Stettin) began operation. In 1868 the town was connected to the railway network. This improved industrial development quite considerably. In 1870 a gas power plant was installed. The town was connected in 1873 by the railway to Dirschau (Tczew) and in 1877 by railway to Stettin. In 1886 a new hospital was built in the town. A new railway line to Nakel (Nakło) was opened in 1894. In the year of 1900 the town obtained both a water supply system and an electricity power plant. In 1902 a railway line to Berent (Kościerzyna) was opened. During the time span 1900–1902 the Konitz ritual murder case & antisemitic pogrom took place. In 1909 a sewage system was installed in the town. In 1912 the Gazeta Chojnicka, the first Polish language newspaper, appeared in the town.[21] Chojnice experienced the heaviest Germanisation in the Prussian partition of Poland.[22]

Poland (1920–1939)

.jpg)

After the regulations of the Treaty of Versailles had become effective in 1920, Chojnice together with 62% of the former province of West Prussia was re-integrated into the Second Polish Republic, which regained independence in 1918, and Polish troops entered the town. A local citizen, Barbara Stammowa, symbolically broke shackles on the balcony of the town hall - in revenge Nazis murdered her in 1939 when the town was re-occupied by Germany.[23] In the interwar period two official visits of Presidents of Poland to Chojnice took place, as Stanisław Wojciechowski visited the town in 1924 and Ignacy Mościcki in 1927.[24] In 1932 a regional museum was opened in Chojnice.[25]

World War II and Nazi German occupation (1939–1945)

During the Nazi German invasion of Poland Wehrmacht troops occupied Chojnice on September 1, 1939, in the morning at 4:45 o'clock. This invasion gave rise to the Battle of Chojnice.

From the beginning of the German occupation, German militiamen attack their Jewish and Polish neighbors. On 26 September 1939 forty people were shot, followed by a priest and 208 psychiatric patients.[26] From late October 1939 through early 1940, mass executions were conducted by SS and the German police as part of the Intelligenzaktion, an action against the Polish intelligentsia. [27] In total, by January 1940 900 Poles and Jews from Chojnice and its surrounding villages were killed.[26]

Hans Kruger - a Nazi activist - became a judge in Chojnice, and during his rule executions of the local population followed[28]

During the occupation, the Annunciation of Mary church was taken over by Protestants and its interior was devastated.[14]

The Pomeranian Griffin, Kashubian Griffin and Home Army Polish underground resistance organisations were active in the area.

Chojnice since 1945

In February 1945 the Red Army captured the town. During the fighting about 800 soldiers died, and the town centre was heavily damaged. After the end of World War II Polish authorities began the reconstruction of the city.

In 2002 a new, modern hospital was opened on the north-west outskirts of the town.[29]

Attractions

The Museum of History and Ethnography in Chojnice opened in 1932. It was damaged during World War II and reopened in 1960.[25] It is located in the medieval town walls and Człuchów Gate.

The town also has a number of medieval and early modern buildings, including several churches. The most prominent churches are the Gothic Basilica of the Beheading of St. John the Baptist in Chojnice and the Baroque Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin Mary Church in Chojnice.

Population

The population of Chojnice has increased generally since the 18th century. However World War I and World War II, reduced the town's population. When the regulations of the Treaty of Versailles became effective in 1920, many Germans left the town. The influence of World War II is evident in the 1948 census showing that the population was reduced by 1,900 people compared to 1933. After World War II Germans inhabitants either fled or were expelled from the city.

Geography

Climate

Climate in this area has mild differences between highs and lows, and there is adequate rainfall year-round. The Köppen Climate Classification subtype for this climate is "Cfb". (Marine West Coast Climate/Oceanic climate).[37]

Sport

Chojniczanka Chojnice is based in the town.

Notable People

.png)

- Michał Kazimierz Radziwiłł (1625–1680), Polish-Lithuanian magnate, starost of Chojnice

- Johann Ernst Gotzkowsky (1710–1775) a Prussian diplomat and merchant of trinkets, silk, taft, porcelain, grain and bills of exchange

- Nathanael Matthaeus von Wolf (1724-1784) was a German botanist, physician, and astronomer

- Johann Daniel Titius (1729–1796), astronomer, physicist, biologist

- Antoni Klawiter (1836-1913) a Roman Catholic and later an independent Polish Catholic priest

- Emil Albert Friedberg (1837–1910) a German jurist and canonist.

- Rudolf Arnold Nieberding (1838–1912), jurist and politician

- Hartwig Cassel (1850–1929) a chess journalist, editor and promoter

- Hugo Heimann (1859–1951), German publisher and politician

- Heinrich Recke (1890–1943), Wehrmacht general

- Willi Apel (1893–1988), German-US musicologist; born here

- Eugeniusz Kłopotek (born 1953) a Polish politician and MEP

- Dariusz Pasieka (born 1965), Polish former professional footballer, over 360 pro games

- Misheel Jargalsaikhan (born 1988) a Polish child actress of Mongolian heritage

- Irmina Gliszczyńska (born 1992) a Polish competitive sailor, competed at the 2016 Summer Olympics

See also

- Chojnice (PKP station)

- Battle of Chojnice

- Konitz affair, an antisemitic riot in 1900.

International relations

Chojnice is twinned with:

|

|

References

- Ludność w gminach. Stan w dniu 31 marca 2011 r. - wyniki spisu ludności i mieszkań 2011 r.

- Stanisław Gierszewski, Chojnice: dzieje miasta i powiatu, Zakład Narodowy im Ossolińskich, 1971, p. 54

- James Minahan, One Europe, Many Nations: A Historical Dictionary of European National Groups, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2000, p. 375, ISBN 0-313-30984-1.

- Nazwy miast Pomorza Gdańskiego - page 46 Hubert Górnowicz, Zygmunt Brocki, Edward Breza - 1999 Tak więc Chojnica (późniejsze Chojnice) jest polską nazwą topograficzną, ponowioną od nazwy rzeki Chojnica

- Chojnice - Urząd Miejski - Historia

- "Kiedy nie pomogły machiny miotające, Krzyżacy postawili szubienice". Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- Karol Górski, Związek Pruski i poddanie się Prus Polsce: zbiór tekstów źródłowych, Instytut Zachodni, Poznań, 1949, p. XXXVII (in Polish)

- Marian Biskup, Oblężenie i odzyskanie Chojnic przez Polskę w r. 1466, "Zeszyty Chojnickie" nr 29, Chojnickie Towarzystwo Przyjaciół Nauk, Chojnice, 2014, p. 15 (in Polish)

- "Z dziejów miasta". Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- Biskup, p. 19

- Górski, p. 89-90, 207

- Witold Look, Sukiennictwo chojnickie, "Zeszyty Chojnickie" nr 29, Chojnickie Towarzystwo Przyjaciół Nauk, Chojnice, 2014, p. 20 (in Polish)

- Look, p. 21

- "Kościół pojezuicki p.w. Zwiastowania Najświętszej Marii Panny". Urząd Miejski w Chojnicach (in Polish, English, and German). Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- "Z PAMIĘTNIKA BURMISTRZA". Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- Jerzy Szews, Filomaci chojniccy, "Zeszyty Chojnickie" nr 29, Chojnickie Towarzystwo Przyjaciół Nauk, Chojnice, 2014, p. 41 (in Polish)

- Szews, p. 42

- Szews, p. 43

- Szews, p. 45-47

- Szews, p. 44. 46

- "ROLA I ZNACZENIE PRASY LOKALNEJ". Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- Chojnickie Towarzystwo Przyjaciół Nauk „ZESZYTY CHOJNICKIE” 2010, nr 25 Paweł Piotr Mynarczyk Sytuacja polityczna i społeczna w Chojnicach od roku 1920 do przewrotu majowego

- Chojnickie Towarzystwo Przyjaciół Nauk „ZESZYTY CHOJNICKIE” 2012, nr 27 Małgorzata Hamerska Miejsca pamięci narodowej w powiecie chojnickim Dolina Śmierci w Igłach pod Chojnicami

- "Panie i Panowie - Prezydent RP". Historia Chojnic (in Polish). Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- "Strona główna - Muzeum Historyczno-Etnograficzne w Chojnicach". chojnicemuzeum.pl. Retrieved 2019-02-27.

- The German War: A Nation Under Arms, 1939–45, Nicholas Stargardt

- Witnesses of War: Children's Lives Under the Nazis, Nicholas Stargardt

- Funktionäre Mit Vergangenheit: Das Gründungspräsidium Des Bundesverbandes Der Vertriebenen Und Das "dritte Reich" 2013 Michael Schwartz page 437 Walter de Gruyter 2013

- "Chojnicki Szpital ma już 10 lat!". Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- August Eduard Preuß: Preußische Lands- und Volkskunde. Königsberg 1835, p. 384, no. 17).

- Johann Gottfried Hofmann: Die Bevölkerung des Preußischen Staats 1837. Berlin 1839, p. 104.

- Michale Rademacher: Deutsche Verwaltungsgeschichte - Landkreis Könitz (2006).

- Neighborhood Dilemmas: The Poles, the Germans and the Jews in Pomerania Along the Vistula River in the 19th and 20th Century : a Collection of Studies Jan Sziling, Mieczysław Wojciechowski Wydawn. Uniw. Mikołaja Kopernika, 2002 page 12

- Meyers Großes Konversationsa-Lexikon, 6. Auflage, 11. Band, Leipzig und Wien 1908, p. 395.

- Der Große Brockhaus, 15. Auflage, 10. Band. Leipzig 1931, p. 389.

- Meyers Enzyklopädisches Lexikon, 9. Auflage, Band 5, Mannheim Wien Zürich 1978, p. 646.

- Climate Summary for Chojnice, Poland

- "National Commission for Decentralised cooperation". Délégation pour l’Action Extérieure des Collectivités Territoriales (Ministère des Affaires étrangères) (in French). Archived from the original on 2013-11-27. Retrieved 2013-12-26.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chojnice. |

- Chojnice city portal website

- www.miastochojnice.pl

- Officers, addresses, phone numbers

- Chamber of Commerce/Tourism

- A site devoted to providing information about city history (Polish language)