Time signature

The time signature (also known as meter signature,[1] metre signature,[2] or measure signature)[3] is a notational convention used in Western musical notation to specify how many beats (pulses) are contained in each measure (bar), and which note value is equivalent to a beat.

4 time signature. The time signature indicates that there are three quarter notes (crotchets) per measure (bar).

In a music score, the time signature appears at the beginning as a time symbol or stacked numerals, such as ![]()

4 (read common time and three-four time, respectively), immediately following the key signature (or immediately following the clef symbol if the key signature is empty). A mid-score time signature, usually immediately following a barline, indicates a change of meter.

There are various types of time signatures, depending on whether the music follows regular (or symmetrical) beat patterns, including simple (e.g., 3

4 and 4

4), and compound (e.g., 9

8 and 12

8); or involves shifting beat patterns, including complex (e.g., 5

4 or 7

8), mixed (e.g., 5

8 & 3

8 or 6

8 & 3

4), additive (e.g., 3+2+3

8), fractional (e.g., 2 1⁄2

4), and irrational meters (e.g., 3

10 or 5

24).

Frequently used time signatures

4, also known as common time (

2, alla breve, also known as cut time or cut-common time (

4; 3

4; and 6

8

Simple vs. compound

Simple

Simple time signatures consist of two numerals, one stacked above the other:

- The lower numeral indicates the note value that represents one beat (the beat unit). This number is typically a power of 2.

- The upper numeral indicates how many such beats constitute a bar.

For instance, 2

4 means two quarter-note (crotchet) beats per bar, while 3

8 means three eighth-note (quaver) beats per bar. The most common simple time signatures are 2

4, 3

4, and 4

4.

By convention, two special symbols are sometimes used for 4

4 and 2

2:

- The symbol

4 time, also called common time or imperfect time. The symbol is derived from a broken circle used in music notation from the 14th through 16th centuries, where a full circle represented what today would be written in 3

2 or 3

4 time, and was called tempus perfectum (perfect time).[4] See Mensural time signatures below. - The symbol

2 and is called alla breve or, colloquially, cut time or cut common time.

Compound

In compound meter, subdivisions (which are what the upper number represents in these meters) of the beat are in three equal parts, so that a dotted note (half again longer than a regular note) becomes the beat. The upper numeral of compound time signatures is commonly 6, 9, or 12 (multiples of 3 in each beat). The lower number is most commonly an 8 (an eighth-note or quaver): as in 9

8 or 12

8.

Examples

In the examples below, bold denotes a more-stressed beat, and italics denotes a less-stressed beat.

Simple: 3

4 is a simple triple meter time signature that represents three quarter notes (crotchets). It is felt as

- 3

4: one and two and three and ...

- 3

Compound: In principle, 6

8 comprises not three groups of two eighth notes (quavers) but two groups of three eighth-note (quaver) subdivisions. It is felt as

- 6

8: one two three four five six ...

- 6

These examples assume, for simplicity, that continuous eighth notes are the prevailing note values. The rhythm of actual music is typically not as regular.

Duple, triple, etc.

Time signatures indicating two beats per bar (whether in simple or compound meter) are called duple meter, while those with three beats to the bar are triple meter. Terms such as quadruple (4), quintuple (5), and so on, are also occasionally used.

Beating time signatures

To the ear, a bar may seem like one singular beat. For example, a fast waltz, notated in 3

4 time, may be described as being one in a bar. Correspondingly, at slow tempos, the beat indicated by the time signature could in actual performance be divided into smaller units.

On a formal mathematical level, the time signatures of, e.g., 3

4 and 3

8 are interchangeable. In a sense, all simple triple time signatures, such as 3

8, 3

4, 3

2, etc.—and all compound duple times, such as 6

8, 6

16 and so on, are equivalent. A piece in 3

4 can be easily rewritten in 3

8, simply by halving the length of the notes.

Other time signature rewritings are possible: most commonly a simple time signature with triplets translates into a compound meter.

Though formally interchangeable, for a composer or performing musician, by convention, different time signatures often have different connotations. First, a smaller note value in the beat unit implies a more complex notation, which can affect ease of performance. Second, beaming affects the choice of actual beat divisions. It is, for example, more natural to use the quarter note/crotchet as a beat unit in 6

4 or 2

2 than the eight/quaver in 6

8 or 2

4. Third, time signatures are traditionally associated with different music styles—it might seem strange to notate a rock tune in 4

8 or 4

2.

Characteristics

The table below shows the characteristics of the most frequently-used time signatures.

| Simple time signatures | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Time signature | Common uses | Simple drum pattern | Video representation |

| 4 4 or (quadruple) |

Common time: Widely used in most forms of Western popular music. Most common time signature in rock, blues, country, funk, and pop[6] | ||

| 2 2 or (duple) |

Alla breve, cut time: Used for marches and fast orchestral music. | ||

| 2 4 (duple) |

Used for polkas, galops, and marches | ||

| 3 4 (triple) |

Used for waltzes, minuets, scherzi, polonaises, mazurkas, country & western ballads, R&B, sometimes used in pop | ||

| 3 8 (triple) |

Also used for the above but usually suggests higher tempo or shorter hypermeter | ||

| Compound time signatures | |||

| Time signature | Common uses | Simple drum pattern | Video representation |

| 6 8 (duple) |

Double jigs, polkas, sega, salegy, tarantella, marches, barcarolles, loures, and some rock music | ||

| 9 8 (triple) |

Compound triple time: Used in triple ("slip") jigs, otherwise occurring rarely ("The Ride of the Valkyries", Tchaikovsky's Fourth Symphony, and the final movement of J.S. Bach's Violin Concerto in A minor (BWV 1041)[7] are familiar examples. Debussy's "Clair de lune" and the opening bars of Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune are also in 9 8) |

||

| 12 8 (quadruple) |

Also common in slower blues (where it is called a shuffle) and doo-wop; also used more recently in rock music. Can also be heard in some jigs like "The Irish Washerwoman". This is also the time signature of the second movement of Beethoven's Pastoral Symphony. | ||

Complex time signatures

Signatures that do not fit the usual duple or triple categories are called complex, asymmetric, irregular, unusual, or odd—though these are broad terms, and usually a more specific description is appropriate. The term odd meter, however, sometimes describes time signatures in which the upper number is simply odd rather than even, including 3

4 and 9

8.[8]

The irregular meters (not fitting duple or triple categories) are common in some non-Western music, but rarely appeared in formal written Western music until the 19th century. Early anomalous examples appeared in Spain between 1516 and 1520,[8] but the Delphic Hymns to Apollo (one by Athenaeus is entirely in quintuple meter, the other by Limenius predominantly so), carved on the exterior walls of the Athenian Treasury at Delphi in 128 BC are in the relatively common cretic meter, with five beats to a foot.[9]

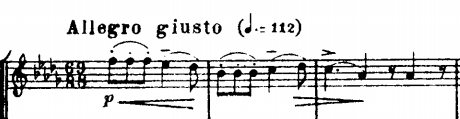

The third movement of Frédéric Chopin's Piano Sonata No. 1 (1828) is an early, but by no means the earliest, example of 5

4 time in solo piano music. Anton Reicha's Fugue No. 20 from his Thirty-six Fugues, published in 1803, is also for piano and is in 5

8. The waltz-like second movement of Tchaikovsky's Pathétique Symphony (shown below), often described as a "limping waltz",[10] is a notable example of 5

4 time in orchestral music.

Examples from 20th-century classical music include:

- Gustav Holst's "Mars, the Bringer of War" and "Neptune, the Mystic" from The Planets (both in 5

4) - Paul Hindemith's "Fuga secunda" in G from Ludus Tonalis (5

8) - the ending of Stravinsky's The Firebird (7

4) - the fugue from Heitor Villa-Lobos's Bachianas Brasileiras No. 9 (11

8) - the themes for the Mission: Impossible television series by Lalo Schifrin (in 5

4) and for Room 222 by Jerry Goldsmith (in 7

4)

In the Western popular music tradition, unusual time signatures occur as well, with progressive rock in particular making frequent use of them. The use of shifting meters in The Beatles' "Strawberry Fields Forever" and the use of quintuple meter in their "Within You, Without You" are well-known examples,[11] as is Radiohead's "Paranoid Android" (includes 7

8).[12]

Paul Desmond's jazz composition "Take Five", in 5

4 time, was one of a number of irregular-meter compositions that The Dave Brubeck Quartet played. They played other compositions in 11

4 ("Eleven Four"), 7

4 ("Unsquare Dance"), and 9

8 ("Blue Rondo à la Turk"), expressed as 2+2+2+3

8. This last is an example of a work in a signature that, despite appearing merely compound triple, is actually more complex. Brubeck's title refers to the characteristic aksak meter of the Turkish karşılama dance.[13]

However, such time signatures are only unusual in most Western music. Traditional music of the Balkans uses such meters extensively. Bulgarian dances, for example, include forms with 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 22, 25 and other numbers of beats per measure. These rhythms are notated as additive rhythms based on simple units, usually 2, 3 and 4 beats, though the notation fails to describe the metric "time bending" taking place, or compound meters. See Additive meters below.

Some video samples are shown below.

Mixed meters

While time signatures usually express a regular pattern of beat stresses continuing through a piece (or at least a section), sometimes composers place a different time signature at the beginning of each bar, resulting in music with an extremely irregular rhythmic feel. In this case, the time signatures are an aid to the performers and not necessarily an indication of meter. The Promenade from Modest Mussorgsky's Pictures at an Exhibition (1874) is a good example. The opening measures are shown below:

Igor Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring (1913) is famous for its "savage" rhythms. Five measures from "Sacrificial Dance" are shown below:

In such cases, a convention that some composers follow (e.g., Olivier Messiaen, in his La Nativité du Seigneur and Quatuor pour la fin du temps) is to simply omit the time signature. Charles Ives's Concord Sonata has measure bars for select passages, but the majority of the work is unbarred.

Some pieces have no time signature, as there is no discernible meter. This is sometimes known as free time. Sometimes one is provided (usually 4

4) so that the performer finds the piece easier to read, and simply has "free time" written as a direction. Sometimes the word FREE is written downwards on the staff to indicate the piece is in free time. Erik Satie wrote many compositions that are ostensibly in free time but actually follow an unstated and unchanging simple time signature. Later composers used this device more effectively, writing music almost devoid of a discernibly regular pulse.

If two time signatures alternate repeatedly, sometimes the two signatures are placed together at the beginning of the piece or section, as shown below:

Detail of score of Tchaikovsky's String Quartet No. 2 in F major, showing a multiple time signature

Detail of score of Tchaikovsky's String Quartet No. 2 in F major, showing a multiple time signature

Additive meters

To indicate more complex patterns of stresses, such as additive rhythms, more complex time signatures can be used. Additive meters have a pattern of beats that subdivide into smaller, irregular groups. Such meters are sometimes called imperfect, in contrast to perfect meters, in which the bar is first divided into equal units.[14]

For example, the time signature 3+2+3

8 means that there are 8 quaver beats in the bar, divided as the first of a group of three eighth notes (quavers) that are stressed, then the first of a group of two, then first of a group of three again. The stress pattern is usually counted as

- 3+2+3

8: one two three one two one two three ...

- 3+2+3

This kind of time signature is commonly used to notate folk and non-Western types of music. In classical music, Béla Bartók and Olivier Messiaen have used such time signatures in their works. The first movement of Maurice Ravel's Piano Trio in A Minor is written in 8

8, in which the beats are likewise subdivided into 3+2+3 to reflect Basque dance rhythms.

Romanian musicologist Constantin Brăiloiu had a special interest in compound time signatures, developed while studying the traditional music of certain regions in his country. While investigating the origins of such unusual meters, he learned that they were even more characteristic of the traditional music of neighboring peoples (e.g., the Bulgarians). He suggested that such timings can be regarded as compounds of simple two-beat and three-beat meters, where an accent falls on every first beat, even though, for example in Bulgarian music, beat lengths of 1, 2, 3, 4 are used in the metric description. In addition, when focused only on stressed beats, simple time signatures can count as beats in a slower, compound time. However, there are two different-length beats in this resulting compound time, a one half-again longer than the short beat (or conversely, the short beat is 2⁄3 the value of the long). This type of meter is called aksak (the Turkish word for "limping"), impeded, jolting, or shaking, and is described as an irregular bichronic rhythm. A certain amount of confusion for Western musicians is inevitable, since a measure they would likely regard as 7

16, for example, is a three-beat measure in aksak, with one long and two short beats (with subdivisions of 2+2+3, 2+3+2, or 3+2+2).[15]

Folk music may make use of metric time bends, so that the proportions of the performed metric beat time lengths differ from the exact proportions indicated by the metric. Depending on playing style of the same meter, the time bend can vary from non-existent to considerable; in the latter case, some musicologists may want to assign a different meter. For example, the Bulgarian tune "Eleno Mome" is written in one of three forms: (1) 7 = 2+2+1+2, (2) 13 = 4+4+2+3, or (3) 12 = 3+4+2+3, but an actual performance (e.g., Smithsonian Eleno Mome) may be closer to 4+4+2+3. The Macedonian 3+2+2+3+2 meter is even more complicated, with heavier time bends, and use of quadruples on the threes. The metric beat time proportions may vary with the speed that the tune is played. The Swedish Boda Polska (Polska from the parish Boda) has a typical elongated second beat.

In Western classical music, metric time bend is used in the performance of the Viennese Waltz. Most Western music uses metric ratios of 2:1, 3:1, or 4:1 (two-, three- or four-beat time signatures)—in other words, integer ratios that make all beats equal in time length. So, relative to that, 3:2 and 4:3 ratios correspond to very distinctive metric rhythm profiles. Complex accentuation occurs in Western music, but as syncopation rather than as part of the metric accentuation.

Brăiloiu borrowed a term from Turkish medieval music theory: aksak. Such compound time signatures fall under the "aksak rhythm" category that he introduced along with a couple more that should describe the rhythm figures in traditional music.[16] The term Brăiloiu revived had moderate success worldwide, but in Eastern Europe it is still frequently used. However, aksak rhythm figures occur not only in a few European countries, but on all continents, featuring various combinations of the two and three sequences. The longest are in Bulgaria. The shortest aksak rhythm figures follow the five-beat timing, comprising a two and a three (or three and two).

Some video samples are shown below.

A method to create meters of lengths of any length has been published in the Journal of Anaphoria Music Theory[17] and Xenharmonikon 16[18] using both those based on the Horograms of Erv Wilson and Viggo Brun's algorithm written by Kraig Grady.

Irrational meters

3 time signature: here there are four (4) third notes (3) per measure. A "third note" would be one third of a whole note, and thus is a half-note triplet. The second measure of 4

2 presents the same notes, so the 4

3 time signature serves to indicate the precise speed relationship between the notes in the two measures.

Irrational time signatures (rarely, "non-dyadic time signatures") are used for so-called irrational bar lengths,[19] that have a denominator that is not a power of two (1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, etc.). These are based on beats expressed in terms of fractions of full beats in the prevailing tempo—for example 3

10 or 5

24.[19] For example, where 4

4 implies a bar construction of four quarter-parts of a whole note (i.e., four quarter notes), 4

3 implies a bar construction of four third-parts of it. These signatures are of utility only when juxtaposed with other signatures with varying denominators; a piece written entirely in 4

3, say, could be more legibly written out in 4

4.

According to Brian Ferneyhough, metric modulation is "a somewhat distant analogy" to his own use of "irrational time signatures" as a sort of rhythmic dissonance.[19] It is arguable whether the use of these signatures makes metric relationships clearer or more obscure to the musician; it is always possible to write a passage using non-irrational signatures by specifying a relationship between some note length in the previous bar and some other in the succeeding one. Sometimes, successive metric relationships between bars are so convoluted that the pure use of irrational signatures would quickly render the notation extremely hard to penetrate. Good examples, written entirely in conventional signatures with the aid of between-bar specified metric relationships, occur a number of times in John Adams' opera Nixon in China (1987), where the sole use of irrational signatures would quickly produce massive numerators and denominators.

Historically, this device has been prefigured wherever composers wrote tuplets. For example, a 2

4 bar of 3 triplet crotchets could arguably be written as a bar of 3

6. Henry Cowell's piano piece Fabric (1920) employs separate divisions of the bar (anything from 1 to 9) for the three contrapuntal parts, using a scheme of shaped noteheads to visually clarify the differences, but the pioneering of these signatures is largely due to Brian Ferneyhough, who says that he finds that "such 'irrational' measures serve as a useful buffer between local changes of event density and actual changes of base tempo".[19] Thomas Adès has also used them extensively—for example in Traced Overhead (1996), the second movement of which contains, among more conventional meters, bars in such signatures as 2

6, 9

14 and 5

24.

A gradual process of diffusion into less rarefied musical circles seems underway. For example, John Pickard's Eden, commissioned for the 2005 finals of the National Brass Band Championships of Great Britain contains bars of 3

10 and 7

12.[20]

Notationally, rather than using Cowell's elaborate series of notehead shapes, the same convention has been invoked as when normal tuplets are written; for example, one beat in 4

5 is written as a normal quarter note, four quarter notes complete the bar, but the whole bar lasts only 4⁄5 of a reference whole note, and a beat 1⁄5 of one (or 4⁄5 of a normal quarter note). This is notated in exactly the same way that one would write if one were writing the first four quarter notes of five quintuplet quarter notes.

Some video samples are shown below.

These video samples show two time signatures combined to make a polymeter, since 4

3, say, in isolation, is identical to 4

4.

Variants

Some composers have used fractional beats: for example, the time signature 2 1⁄2

4 appears in Carlos Chávez's Piano Sonata No. 3 (1928) IV, m. 1. Both 2 1⁄2

4 and 1 1⁄2

4 appear in the fifth movement of Percy Grainger's Lincolnshire Posy.

Music educator Carl Orff proposed replacing the lower number of the time signature with an actual note image, as shown at right. This system eliminates the need for compound time signatures, which are confusing to beginners. While this notation has not been adopted by music publishers generally (except in Orff's own compositions), it is used extensively in music education textbooks. Similarly, American composers George Crumb and Joseph Schwantner, among others, have used this system in many of their works.

Another possibility is to extend the barline where a time change is to take place above the top instrument's line in a score and to write the time signature there, and there only, saving the ink and effort that would have been spent writing it in each instrument's staff. Henryk Górecki's Beatus Vir is an example of this. Alternatively, music in a large score sometimes has time signatures written as very long, thin numbers covering the whole height of the score rather than replicating it on each staff; this is an aid to the conductor, who can see signature changes more easily.

Early music usage

Mensural time signatures

In the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries, a period in which mensural notation was used, four basic mensuration signs determined the proportion between the two main units of rhythm. There were no measure or bar lines in music of this period; these signs, the ancestors of modern time signatures, indicate the ratio of duration between different note values. The relation between the breve and the semibreve was called tempus, and the relation between the semibreve and the minim was called prolatio. The breve and the semibreve use roughly the same symbols as our modern double whole note (breve) and whole note (semibreve), but they were not limited to the same proportional values as are in use today. There are complicated rules concerning how a breve is sometimes three and sometimes two semibreves. Unlike modern notation, the duration ratios between these different values was not always 2:1; it could be either 2:1 or 3:1, and that is what, amongst other things, these mensuration signs indicated. A ratio of 3:1 was called complete, perhaps a reference to the Trinity, and a ratio of 2:1 was called incomplete.

A circle used as a mensuration sign indicated tempus perfectum (a circle being a symbol of completeness), while an incomplete circle, resembling a letter C, indicated tempus imperfectum. Assuming the breve is a beat, this corresponds to the modern concepts of triple meter and duple meter, respectively. In either case, a dot in the center indicated prolatio perfecta (compound meter) while the absence of such a dot indicated prolatio imperfecta (simple meter).

A rough equivalence of these signs to modern meters would be:

.svg.png)

8 meter;.svg.png)

4 meter;.svg.png)

8 meter;.svg.png)

4 meter.

N.B.: in modern compound meters the beat is a dotted note value, such as a dotted quarter, because the ratios of the modern note value hierarchy are always 2:1. Dotted notes were never used in this way in the mensural period; the main beat unit was always a simple (undotted) note value.

Proportions

Another set of signs in mensural notation specified the metric proportions of one section to another, similar to a metric modulation. A few common signs are shown:[21]

Often the ratio was expressed as two numbers, one above the other,[22] looking similar to a modern time signature, though it could have values such as 4

3, which a conventional time signature could not.

Some proportional signs were not used consistently from one place or century to another. In addition, certain composers delighted in creating "puzzle" compositions that were intentionally difficult to decipher.[23]

In particular, when the sign ![]()

References

- Alexander R. Brinkman, Pascal Programming for Music Research (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990): 443, 450–63, 757, 759, 767. ISBN 0226075079; Mary Elizabeth Clark and David Carr Glover, Piano Theory: Primer Level (Miami: Belwin Mills, 1967): 12; Steven M. Demorest, Building Choral Excellence: Teaching Sight-Singing in the Choral Rehearsal (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2003): 66. ISBN 0195165500; William Duckworth, A Creative Approach to Music Fundamentals, eleventh edition (Boston, MA: Schirmer Cengage Learning, 2013): 54, 59, 379. ISBN 0840029993; Edwin Gordon, Tonal and Rhythm Patterns: An Objective Analysis: A Taxonomy of Tonal Patterns and Rhythm Patterns and Seminal Experimental Evidence of Their Difficulty and Growth Rate (Albany: SUNY Press, 1976): 36–37, 54–55, 57. ISBN 0873953541; Demar Irvine, Reinhard G. Pauly, Mark A. Radice, Irvine’s Writing about Music, third edition (Portland, Oregon: Amadeus Press, 1999): 209–10. ISBN 1574670492.

- Henry Cowell and David Nicholls, New Musical Resources, third edition (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996): 63. ISBN 0521496519 (cloth); ISBN 0521499747 (pbk); Cynthia M. Gessele, "Thiéme, Frédéric [Thieme, Friedrich]", The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell (London: Macmillan Publishers, 2001); James L. Zychowicz, Mahler's Fourth Symphony (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2005): 82–83, 107. ISBN 0195181654.

- Edwin Gordon, Rhythm: Contrasting the Implications of Audiation and Notation (Chicago: GIA Publications, 2000): 111. ISBN 1579990983.

- G. Augustus Holmes (1949). The Academic Manual of the Rudiments of Music. London: A. Weekes; Stainer & Bell. p. 17. ISBN 9780852492765.

- Willi Apel, The Notation of Polyphonic Music 900–1600, fifth edition, revised and with commentary; The Medieval Academy of America Publication no. 38 (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Medieval Academy of America, 1953): 147–48.

- Scott Schroedl, Play Drums Today! A Complete Guide to the Basics: Level One (Milwaukee: Hal Leonard Corporation, 2001), p. 42. ISBN 0-634-02185-0.

- See File:Bach BVW 1041 Allegro Assai.png for an excerpt from the violin part of the final movement.

- Tim Emmons, Odd Meter Bass: Playing Odd Time Signatures Made Easy (Van Nuys: Alfred Publishing, 2008): 4. ISBN 978-0-7390-4081-2. "What is an 'odd meter'?...A complete definition would begin with the idea of music organized in repeating rhythmic groups of three, five, seven, nine, eleven, thirteen, fifteen, etc."

- Egert Pöhlmann and Martin L. West, Documents of Ancient Greek Music: The Extant Melodies and Fragments, edited and transcribed with commentary by Egert Pöhlmann and Martin L. West (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2001): 70–71, 85. ISBN 0-19-815223-X.

- "Tchaikovsky's Symphony # 6 (Pathetique), Classical Classics, Peter Gutmann". Classical Notes. Retrieved 2012-04-20.

- Edward Macan, Rocking the Classics: English Progressive Rock and the Counterculture (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997): 48. ISBN 978-0-19-509888-4.

- Radiohead (musical group). OK Computer, vocal score with guitar accompaniment and tablature (Essex, England: IMP International Music Publications; Miami, FL: Warner Bros. Publications; Van Nuys, Calif.: Alfred Music Co., Inc., 1997): . ISBN 0-7579-9166-1.

- Manuel, Peter (1988). Popular Musics of the Non-Western World: An Introductory Survey (rev. ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 131. ISBN 9780195063349.

- Gardner Read, Music Notation: A Manual of Modern Practice (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, Inc., 1964):

- Constantin Brăiloiu, Le rythme Aksak, Revue de Musicologie 33, nos. 99 and 100 (December 1951): 71–108. Citation on pp. 75–76.

- Gheorghe Oprea, Folclorul muzical românesc (Bucharest: Ed. Muzicala, 2002), ISBN 973-42-0304-5

- http://anaphoria.com/journal.html

- http://frogpeak.org/fpartists/fpchalmers.html

- "Brian Ferneyhough", The Ensemble Sospeso

- John Pickard: Eden, full score, Kirklees Music, 2005.

- Willi Apel, The Notation of Polyphonic Music 900–1600, fifth edition, revised with commentary; The Medieval Academy of America Publication no. 38 (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Mediaeval Academy of America, 1953), p. 148.

- Willi Apel, The Notation of Polyphonic Music 900–1600, fifth edition, revised with commentary; The Medieval Academy of America Publication no. 38 (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Mediaeval Academy of America, 1953), p. 147.

- Ernst Friedrich Richter, A Treatise on Canon and Fugue: Including the Study of Imitation, translated from third German edition by Arthur W. Foote (Boston: Oliver Ditson, 1888): 38. [ISBN unspecified].