Commodore 64 software

The Commodore 64 amassed a large software library of nearly 10,000 commercial titles, covering most genres from games to business applications, and many others.

Applications, utility, and business software

While the 1541 disk drive's slow performance made the Commodore 64 mostly unsuitable as a business computer,[1] it was still widely used for many important tasks, including computer graphics creation, desktop publishing, and word processing. Info 64, the first magazine produced with desktop publishing tools, was created on and dedicated to the Commodore platform.

The best known art package was perhaps KoalaPainter, primarily because of its own custom graphics tablet user interface - the KoalaPad. Another popular drawing program for the C64 was Doodle!. A Commodore 64 version of The Print Shop existed, allowing users to generate signs and banners with a printer. "The Newsroom" was a desktop publishing suite. Lightpens and CAD drawing software were also commercially produced, such as the Inkwell Lightpen and related tools.

There were many prepackaged wordprocessors available for the Commodore 64, such as PaperClip and Vizawrite, but a popular DIY program was SpeedScript, which was available as a type-in program from Compute!'s Gazette.

The MultiPlan spreadsheet application from Microsoft was ported to the Commodore 64, where it competed against established packages such as Calc Result. The first Lotus 1-2-3-like integrated software package for the 64 was Viza Software's Vizastar.[2][3] A complete office suite arrived in the form of British made Mini Office II. In Germany and Scandinavia, many popular application programs were published by German company Data Becker. The typical C64 spreadsheet could store 64 columns and 255 rows, or 16,000 cells, but only 5-10% of them could be used at any one time, due to RAM limitations.[4]

Serious Commodore 64 business users, however, were drawn to GEOS. Due to its speed, ease of use, and full suite of office applications and utility software, GEOS provided a work environment similar to that of an early Apple Macintosh. Arguably the best office applications appeared on GEOS because it was graphically advanced and not limited by the Commodore 64's screen area of 40-columns. Being a fully-fledged OS, GEOS brought the arrival of many add-on fonts, accessories, and applications. It also supported most Commodore 64 peripherals and models of third-party printers. KoalaPad and Lightpen users could use GEOS too, which greatly increased the amount of clip art available for the platform. GEOS proved very popular because of low price for the necessary hardware (and of course the capability of the OS). This was due in part to the aggressive pricing of the Commodore 64 as a games machine and home computer (With rebates, the C64 was going for as little as US$100 at the time). This was in comparison to a typical PC for US$2000 (which required MS-DOS, and another $99 for Windows 1.0) or the venerable Mac 512K Enhanced also $2000.

There were numerous sound editing tools for the Commodore 64. Commodore released music composition software which included a keyboard overlay suited for early model Commodore 64s. Software titles such as the Music Construction Set were available for users to compose music with notes, however the only tools which really pushed the C64's sonic capability to the full were mostly demoscene music tools, or pure assembly language. MIDI expansion cartridges and speech synthesizing hardware was also available for more serious musicians. The Prophet64 cartridge was recently released and features a suite of GUI-style applications for sequencing music, drum and rhythm synthesis, MIDI DIN-sync, and taking advantage of the SID chip in other ways, effectively turning the C64 into a true musical instrument that anyone can use. There was also software which could be used to make the Commodore 64 speak, the best-known being SAM.

The first screen shows the C64's BASIC with a small program. The BASIC interpreter does not only allow the user to write programs, but it is also used as command prompt, so in order to load a program a BASIC command needs to be entered.

- KoalaPainter is an early paint program. It uses two screens. The first displays a menu and the second is the picture that is being worked on. The program is controlled either by a joystick or with a graphics tablet that was also sold by Koala.

- Magic Desk is an application by Commodore that tries to resemble a real type writer. It contains basic editing functions though.

- Multiplan is a text-based spreadsheet application, written by Microsoft.[5]

- Vizawrite is another text-based word processor for the C64, but looks more like the professional word processors of the early 80s.

- GEOS was a graphical user interface, first released in 1987. It was a small revolution at its time, because until then GUIs, other than Apple II Desktop/MouseDesk, were mostly available for the much more powerful 16-bit machines.

- geoPaint is a paint program for GEOS. Beside the small resolution it had all capabilities of other GUI-based drawing programs of its time.

- geoWrite is a word processor for GEOS. It did not only have a GUI, but also supported many different styles and fonts with the WYSIWYG principle, unlike the other word processors on the C64.

- UIFLI (Underlay Interlace Flexible Line Interpreter) is a Graphicsmode on the Commodore 64 invented by DeeKay and Crossbow of Crest in 1995.

Games

Think back for a minute to the first program you ever saw on a Commodore 64. Chances are it was a game, if you've had a 64 for more than a couple of years.

— Compute!'s Gazette, 1986[6]

By 1985, games were estimated to make up 60 to 70% of Commodore 64 software.[7] Due in part to its advanced sound and graphic hardware, and to the quality and quantity of games written for it, the C64 became better known as a gaming and home entertainment platform than as a serious business computer. Its large installed user base encouraged commercial companies to flood the market with game software, even up until Commodore's demise in 1994. In total over 23,000 unique game titles exist for the Commodore 64.[8]

International Soccer was Commodore's best first-party game; otherwise "the normal standard for Commodore software is mediocrity", InfoWorld stated in 1984.[9] The company did not publish many other games for the C64, instead releasing game cartridges primarily from the failed MAX Machine for the C64. Commodore included an "Ultimax" mode in the Commodore 64's hardware, which allowed the computer to emulate a MAX machine for this purpose.

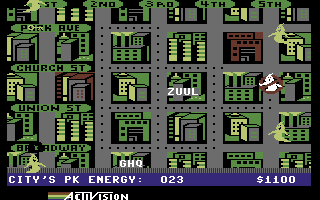

However, aside from the initial Commodore cartridges, very few cartridge-based games were released for the Commodore. Most third-party game cartridges came from Llamasoft, Activision, and Atarisoft, however some of these games found their way into disk and tape versions too. Only later, when the failed C64GS console was produced, did cartridges make a brief comeback, including the production of a few more cartridge-only games. Crackers managed to port these games to disk later on.

While the 1541 floppy disk drive quickly became universal in the US, in Europe it was common for prepackaged commercial game software to either come on floppy disk or cassette-tape format, and sometimes both. Cassette-based games were usually cheaper than their disk-based counterparts; however, due to the Datasette's lack of speed and random access, many large games (such as role-playing video games) were never made for the cassette format. Despite this, a great deal of software was published only on the cassette format in Europe, including many "budget" games produced by companies like Mastertronic, Firebird, and Codemasters which were released on cassette only and sold for a fraction of the price of full-price commercial software.

Whilst many commercial software companies produced prepackaged game software, an abundant supply of free software was also available. What is noticeable from the Commodore 64's game catalog is that a rather large selection of all C64 games were programmed non-commercially by average Commodore 64 users, with editors included in some games, e.g. Boulder Dash Construction Kit, Pinball Construction Set, SEUCK, The Quill, GameMaker. Given the accessibility of BASIC on the Commodore 64, many BASIC games were created and also ported from other computer platforms and modified for the Commodore 64. In addition, many games exist that were released as Type-in programs from numerous magazines, especially European Commodore magazines. Many books and magazines were published containing listings for games, and public domain software was developed and released from both BBS systems and public domain libraries such as "Binary Zone" in the UK.

There were many classic must-have games produced on the Commodore 64, perhaps too many to mention, including versions of classic video games. Of particular note, the smash hit Impossible Mission produced by Epyx was originally designed for the Commodore 64. Epyx's multievent games (Summer Games, Winter Games, World Games, and California Games) were very popular, as well as perhaps the first driving game with split-screen dynamics, Pitstop II. Most of these games eventually made an appearance on the Commodore DTV joystick unit many years later. Other hit games such as Boulder Dash, The Sentinel, Archon, and Elite were all given Commodore 64 versions. Cassette users may remember titles such as Master of Magic, Rocketball, One Man and His Droid, and Spellbound on Mastertronic's budget labels. Other notable titles on the Commodore 64 include the Ultima and Bard's Tale role-playing game series. Hewson/Graftgold were responsible for several well-received C64 titles including Paradroid and Uridium—made famous for their metallic bas-relief styled graphic effects and addictive gameplay. System 3 produced The Last Ninja action adventure series originally on the C64. Armalyte, a groundbreaking shoot 'em up title from Thalamus Ltd, and Turrican I & II are among some of the highest rated games for the Commodore 64 (according to Zzap64, which awarded "Gold Medals" to these games).

Notable game designers for the Commodore 64 are: Paul Norman, Danielle Barry (aka Dan Bunten), Andrew Braybrook, Stephen Landrum, Tim and Chris Stamper, Jeff Minter and Tony Gibson just to name a few.

During the final mainstream commercial years of the Commodore 64, Issue 38 of Commodore Format magazine in November 1993 awarded the only 100% rating ever given to a Commodore 64 game in any major Commodore 64 publication. As no game had ever received such a high rating before, and as the commercial Commodore 64 scene was winding down in the mid-1990s, the awarding of 100% was seen as somewhat controversial. The game, titled Mayhem in Monsterland, was developed to exploit a multitude of programming tricks and quirks in the Commodore 64's hardware to the maximum. The impressive use of non-standard colors and scrolling resulted in perhaps the most graphically stunning game ever produced for the Commodore 64. The gameplay itself is similar to that of Nintendo's Super Mario Bros. and SEGA's Sonic the Hedgehog.

Whilst mainstream commercial activity for games no longer exists for the C64, many enthusiasts and hobbyists still write games for the platform. In addition, a few small publishers still sell game software.

Commodore 64 games continue to inspire developers and gamers on modern platforms such as iOS with many games being produced using similar styles of game-play mechanics to those from the Commodore 64 era.

Type-ins, bulletin boards, and disk magazines

Besides prepackaged commercial software, the C64, like the VIC before it, had a large library of type-in programs. Numerous computer magazines offered type-in programs, usually written in BASIC or assembly language or a combination of the two. Because of its immense popularity, many general-purpose magazines that supported other computers offered C64 type-ins (Compute! was one of these), and at its peak, there were many magazines in North America (Ahoy!, Commodore Magazine, Compute!'s Gazette, Power/Play, RUN and Transactor ) dedicated to Commodore computers exclusively. These magazines sometimes had disk companion subscriptions available at extra cost with the programs stored on disk to avoid the need to type them in. The disk magazine Loadstar offered fairly elaborate ready-to-run programs, music, and graphics. Books of type-ins were also common, especially in the machine's early days. There were also many books publishing type-ins for the C-64, sometimes programs that had originally appeared in one of the magazines, but books containing original software were also available.[10]

A large library of public domain and freeware programs, distributed by online services such as Q-Link and CompuServe, BBSs, and user groups also emerged. Commodore also maintained an archive of public domain software, which it offered for sale on diskette.[11] Despite limited RAM and disk capacity, the Commodore 64 was a popular platform for BBS hosting. Some of the most popular installations included the highly optimized and fast Blue Board program, and the Color64 BBS System, which allowed the use of color PETSCII graphics. Many BBS sysops used high-capacity floppy drives like the SFD-1001 or hard drives such as the Lt. Kernal.

Software cracking

The C64 software market had widespread problems with copyright infringement. There were many kinds of copy protection systems employed on both cassette and floppy disk, to prevent the unauthorized copying of commercial Commodore 64 software. Practically all of them were worked around or defeated by crackers and warez groups. The popularity of this activity has been attributed to the large Commodore 64 user base.

Many BBSs offered cracked commercial software, sometimes requiring special access and usually requiring users to maintain an upload/download ratio. A large number of warez groups existed, including Fairlight, which continued to exist more than a decade after the C64's demise. Some members of these groups turned to telephone phreaking and credit card or calling card fraud to make long-distance calls, either to download new titles not yet available locally, or to upload newly cracked titles released by the group.

Not all Commodore 64 users had modems however. For these people, many warez group "swappers" maintained contacts throughout the world. These contacts would usually mass mail cracked floppy disks through the postal service. Also, sneakernets existed at schools and businesses all over the world, as friends and colleagues would trade (and usually later copy) their software collections. At a time before the Internet was widespread, this was the only way for many users to amass huge software libraries. Also, and particularly in Europe, groups of people would hold copy-parties explicitly to copy software, usually irrespective of software licence.

Several popular utilities were sold that contained custom routines to defeat most copy-protection schemes in commercial software. (Fast Hack'em—probably the most popular example—was itself widely redistributed.) Pirates Toolbox was another popular set of tools for copying disks and removing copy protection. Tapes could be copied with special software, but often it was simply done by dubbing the cassette in a dual deck tape recorder, or by relying on an Action Replay cartridge to freeze the program in memory and save to cassette. Cracked games could often be copied manually without any special tools. In Europe, some hardware devices, colloquially known as "black boxes" were available under the counter that connected two C1530 tape decks together at the connection point to the C64 permitting a copy to be made whilst loading a game. This overcame the difficulties in direct dubbing of later games using the high speed loaders that were developed to overcome the very long load times.

BASIC

Like most computers from the late 1970s and 1980s, the Commodore 64 came with a version of the BASIC programming language. It was used for both writing software and for performing the duties of an operating system such as loading software and formatting disks.

The onboard BASIC programming language offered no easy way to tap the machine's advanced graphics and sound capabilities. Accessing these associated memory addresses to make use of the advanced features required using the PEEK and POKE commands, third-party BASIC extensions, such as Simons' BASIC, or to program in assembly language. Commodore had a better implementation of BASIC but chose to ship the C64 with the same BASIC 2.0 used in the VIC-20 to minimize cost. This, however, did not stop countless people making thousands of programs in the BASIC V2 language, and teaching people their first steps in computer programming.

Music

The MOS Technology 6581 SID is the sound chip for the C64, for which many music software programs were written. A musical software tool for the C64, was Kawasaki Synthesizer created in 1983.

Development tools

Aside from games and office applications such as word processors, spreadsheets, and database programs, the C64 was well equipped with development tools from Commodore as well as third-party vendors. Various assembler solutions were available; the MIKRO assembler came in ROM cartridge form and integrated seamlessly with the standard BASIC screen editor. The PAL Assembler by Brad Templeton was also popular. Several companies sold BASIC compilers, C compilers and Pascal compilers, and a subset of Ada, to mention but a few popular languages available for the machine.

The likely most popular entertainment oriented development suite was the Shoot'Em-Up Construction Kit, affectionately known as SEUCK. SEUCK allowed those non-skilled in programming to create original, professional-looking shooting games. Garry Kitchen's Gamemaker and Arcade Game Construction Kit also allowed non-programmers to create simple games with little effort. Text adventure game tools included The Quill and Graphic Adventure Creator development suites. The Pinball Construction Set gave users a pinball machine to design.

Modern-Day Development Tools

Software development on the Commodore 64 never really stopped. There are many tools available today, including IDEs such as CBM prg Studio, Relaunch64, and WUDSN IDE, which is a plug-in for the open source Eclipse IDE. Along with small C compilers such as cc65, there are many assemblers and cross assemblers to be used on modern day PCs:

- Turbo Assembler

- Kick Assembler by Mads Nielsen

- dasm

- acme

- ca65 (which is part of cc65.)

- c64asm

C64List by Jeff Hoag is both a cross assembler and cross-platform BASIC editor/tokenizer that allows developers to write mixed BASIC/assembly programs in a text file on a PC and compile it into a single .prg file that can be executed on an actual C64 or emulator.

Tools such as PuCrunch, an LZ77 data and executable self extracting compression program, are also available released under GNU LGPL. Sprite editors like Sprite Pad allow you to design C64 Sprites and animations using Windows. GoatTracker allows you to write music using modern OSs and uses the ReSID engine.

Using CodeNet it is possible to transfer and execute programs to a C64 via a TCP/IP network cable from a PC. Although this does require an Ethernet adapter on the C64 such as Individual Computers RR-Net or an appropriate version of the 1541 Ultimate.

Retrocomputing efforts

The magnetic tapes and disks upon which home computer software was stored are decaying at an alarming rate. In order to preserve game software and information, efforts are underway to copy from these degrading media onto fresh media which will help ensure a long life for the software and make it available for emulation and archiving. In addition, there are other efforts to archive Commodore 64 documentation, software manuals, magazine articles, and other nostalgia (such as software packaging artwork, game screenshots, and Commodore 64 TV commercials). Commodore 64 game software has been remarkably well documented and preserved - a considerable feat when taking the amount of software available for the platform into consideration.

The GameBase 64 (GB64) organization has an online database of game information, which at version 7 holds information for 21,000 unique game titles. The database is still growing as new information comes to light. Besides the online database a downloadable offline version exists. Using one of the frontends GameBase (Windows only) or jGameBase (platform independent) you can conveniently browse the database entries and directly start them in an emulator. The GoodGB64 variant of Cowering's Good Tools allows users to audit their C64 game collections using the GameBase64 database.

There are tools available to transfer original 1541 floppy discs to or from the PC. The Star Commander is a DOS-based tool, cbm4linux is a Linux tool, and cbm4win is a Windows tool to transfer data from an original floppy drive to the PC, or vice versa, using a simple X-cable. There are also tools available, 64HDD, to allow your C64 to directly load D64 software stored on your PC using the same cables. The Individual Computers Catweasel allows PC users to use their own floppy drive to read C64 disks.

In addition, there is now a growing number of emulators available, which allow the use of an emulated C64 on modern computing hardware. These include VICE, which is free and runs on most modern as well as some older platforms; CCS64, which is available for Windows and is written by Per Håkan Sundell; and Power64, which has versions for Mac OS X and OS 9.

Also the Quantum Link service has been reconstructed as Quantum Link Reloaded. It can be accessed with a real Commodore 64, or through the VICE emulator.

Special hardware has also been designed to aid the conservation of software, such as the IDE64 cartridge, which allows the user to connect a modern PC IDE ATA hard drive or a CompactFlash flashcard directly to the machine, giving the possibility to copy software onto the hard drive and use it from there, preventing wear on a decades-old floppy disk.

Nintendo's Virtual Console service offers Commodore 64 games for download on the Wii console in North America and Europe.

References

- Perry, Tekla S.; Wallich, Paul (March 1985). "Design case history: the Commodore 64" (PDF). IEEE Spectrum: 48–58. ISSN 0018-9235. Retrieved 2011-11-12.

- "Vizastar for the Commodore 64". Archived from the original on 2013-04-21.

- "RUN Issue 26 1986 Feb".

- "RUN Magazine Issue 35".

- Microsoft: The Early Days from the personal website of Richard Brodie

- Yakal, Kathy (June 1986). "The Evolution of Commodore Graphics". Compute!'s Gazette. pp. 34–42. Retrieved 2019-06-18.

- Waite, Mitchell; Lafore, Robert; Volpe, Jerry (1985). "The C64 Mode". The Official Book for the Commodore 128 Personal Computer. Howard W. Sams & Co. p. 80. ISBN 0-672-22456-9.

- Gamebase64 main page

- Mace, Scott (1984-04-09). "Atarisoft vs. Commodore". InfoWorld. p. 50. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- "C64 Type-In Books". Archived from the original on July 20, 2011.

- "CBM Public Domain".