Commodore Datasette

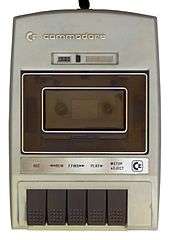

The Commodore 1530 (C2N) Datasette, later also Datassette (a portmanteau of data and cassette), is Commodore's dedicated magnetic tape data storage device. Using compact cassettes as the storage medium, it provides inexpensive storage to Commodore's 8-bit home/personal computers, notably the PET, VIC-20, and C64. A physically similar model, Commodore 1531, was made for the Commodore 16 and Plus/4 series computers.

Description and history

Typical compact cassette interfaces of the late 1970s use a small controller in the computer to convert digital data to and from analog tones. The interface is then connected to the cassette deck using normal sound wiring like RCA jacks or 3.5mm phone jacks. This sort of system was used on the Apple II[1] and Color Computer, as well as many S-100 bus systems, and allow them to be used with any cassette player with suitable connections.[2]

In the Datasette, instead of writing two tones to tape to indicate bits, patterns of square waves are used, including a parity bit. Programs are written twice to tape for error correction; if an error is detected when reading the first recording, the computer corrects it with data from the second.[3] The Datasette has built-in analog-to-digital converters and audio filters to convert the computer's digital data into analog sound and vice versa. Connection to the computer is done via a proprietary edge connector (Commodore 1530) or mini-DIN connector (1531). The absence of recordable audio signals on this interface makes the Datasette and clones the only cassette recorders usable with Commodore computers, until aftermarket converters made the use of ordinary recorders possible.

Because of its digital format the Datasette is both more reliable than other data cassette systems and very slow,[3][4] transferring data at around 50 bytes per second; even the very slow Commodore 1541 floppy drive is much faster. After the Datasette's launch, however, special turbo tape software appeared, providing much faster tape operation (loading and saving). Such software was integrated into most commercial prerecorded applications (mostly games), as well as being available separately for loading and saving the users' homemade programs and data. These programs were only widely used in Europe, as the US market had long since moved onto disks.

Datasettes can typically store about 100 kByte per 30 minute side.[5] The use of turbo tape and other fast loaders increased this number to roughly 1000 kByte.

The Datasette was more popular outside than inside the United States. U.S. Gold, which imported American computer games to Britain, often had to wait until they were converted from disk because most British Commodore 64 owners used tape,[6][7] while the US magazine Compute!'s Gazette reported that by 1983 "90 percent of new Commodore 64 owners bought a disk drive with their computer".[8] Computer Gaming World reported in 1986 that British cassette-based software had failed in the United States because "97% of the Commodore systems in the USA have disk drives";[9] by contrast, MicroProse reported in 1987 that 80% of its 100,000 sales of Gunship in the UK were on cassette.[10] In the United States disk drives quickly became standard, despite the 1541 costing roughly five times as much as a Datasette. In most parts of Europe, the Datasette was the medium of choice for several years after its launch, although floppy disk drives were generally available. The inexpensive and widely available audio cassettes made the Datasette a good choice for the budget-aware home computer mass market.

Interface

The Datasette has only one connection cable, with a 0.156-inch (4.0 mm)–spacing[11] PCB edge connector at the computer end. All input/output signals to the Datasette are all digital, and so all digital-to-analog conversion, and vice versa, is handled within the unit. Power is also included in this cable. The pinout is ground, +5 V DC, motor, read, write, key-sense.[12] The sense signal monitors the play, rewind, and fast-forward buttons but cannot differentiate between them. A mechanical interlock prevents any two of them from being pressed at the same time. The motor power is derived from the computer's unregulated 9 V DC supply[13] via a transistor circuit.[14]

Physical coding

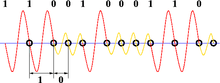

To record physical data, the zero-crossing from positive to negative voltage of the analog signal is measured. The resulting time between these positive to negative crossings is then compared to a threshold to determine whether the time since the last crossing is short (0) or long (1).[15] Note the lower amplitude for the shorter periods.

A circuit in the tape unit transforms the analog signal into a logical 1 or 0, which is then transmitted to the computer via the tape connector. Inside the computer, the first Complex Interface Adapter (6526) in the C64 senses when the signal goes from one to zero. This event is called trigger and causes an interrupt request. This event can be handled by a handler code, or simply discovered by testing bit 4 of location $DC0D. The points that trigger this event are indicated by the black circles in the figure.[15]

Inside the tape device the read head signal is fed into an operational amplifier (1) whose output signal is DC-filtered. Op-amp (2) amplifies and feeds an RC filter. Op-amp (3) amplifies the signal again followed by another DC filter. Op-amp (4) amplifies the signal into clipping the sine-formed signal. The positive and negative rails for all op-amps are wired to +5V DC and GND. The clipped signal therefore fits into the TTL electrical level window of the Schmitt trigger step that in turn feeds the digital cassette port.[16]

On the PAL version of the C64, the time granularity is 1.014 μs (for NTSC 0.978 μs). Since each bit uses 3284 clock cycles this means 3284 * 1.014 μs = 3330 μs/bit. or a 300 bit/s data rate.

Once the bits can be decoded, they are fed into a shift register and are continuously compared to a special bit sequence. This bit sequence can also be seen as a byte. A bit-sequence match means that the stream is byte-synchronized. The first byte to compare with is called lead-in byte. If matched, it's compared to the sync byte as well.[15]

An example: Turbo Tape 64 has a lead-in byte $02 (binary 00000010), sync byte $09 (binary 00001001) and a following sync sequence of $08, $07, $06, $05, $03, $02, $01.[15]

Practical handling

The way to arrange a "directory" and find software on tapes was accomplished by using an inlay sheet with counter position noted, and program name next to it. Unlike other computers' tape systems, Commodore's allowed for named files so the file could also be loaded from the beginning with the names of each file encountered printed to the computer's display.

The physical shape of the Commodore Datasette 1530/31 is a weight of 0.7 kg and measurement 19.5 cm wide, 5 cm high and 15 cm deep.

Main models

Used with the PET, VIC-20, C64/128

There are at least four main models of the 1530/C2N Datassette:

- The original modified Sanyo M1540A cassette drive, built into the earliest models of PET in 1977. This was a standard shoebox tape recorder with a corner of the case removed and modified electronics; a Commodore PCB was installed internally in place of the Sanyo electronics. To disguise the Sanyo brand, Commodore simply fitted a Commodore badge over the original logo. [17]

- The second built-in Datassette in the PET 2001: another standard consumer model (sold in some markets as CCE CCT1020) modified with a Commodore PCB. Black cassette lid, five white keys, no tape counter, no SAVE LED [18]

- Black body original-shape model, black cassette lid, five black keys, no tape counter, no SAVE LED

- White body original-shape model, black cassette lid, five black keys, with tape counter, no SAVE LED

- White body new-shape model, silver cassette lid, six black keys, with white tape counter SAVE LED on left side

- White body new-shape model, silver cassette lid, six black keys, with tape counter and a red SAVE LED on the right

- As above but with black pattern and silvery Commodore logo, six black keys, tape counter and a red SAVE LED on right side

The first two external models were made as PET peripherals, and styled after the PET 2001 built-in tape drive. The latter two were styled and marketed for the VIC-20 and C64. All 1530s are compatible with all those computers, as well as the C128.

In addition to this, some models came with a small hole above the keys, to allow access to the adjustment screw of the tape head azimuth position. A small screwdriver can thus easily be used to effect the adjustment without disassembling the Datassette's chassis.

Confusingly, the Datassette at various times was sold both as the C2N DATASETTE UNIT Model 1530 and as the 1530 DATASSETTE UNIT Model C2N. Note the difference in spelling (one S versus two) used on the original product packaging.[19]

Like Datasette models, the recording format is compatible across computers; the VIC, for example, can read PET cassettes.[20][21]

Used with the C16/116 and Plus/4

Similar in physical appearance to the 1530/C2N models is the Commodore 1531, made for the Commodore 16 and Plus/4 series computers. This has a Mini-DIN connector in place of the PCB edge connector. This can be used with a C64/128 via an adaptor, which was supplied by Commodore with some units.

- Black/charcoal body new shape model, silver cassette lid, six light gray keys, with tape counter and a red SAVE LED

Models

The third, most common version of the 1530 C2N Datassette

The third, most common version of the 1530 C2N Datassette Datassette 1531

Datassette 1531 One of the few clones

One of the few clones

See also

References

- "The Apple II Cassette Interface". Apple Orchard. Spring 1981. p. 57.

- Friedman, Herb (February 1983). "The Five Friendliest Computers". Popular Mechanics. p. 97.

- De Ceukelaire, Harrie (February 1985). "How TurboTape Works". Compute!. p. 112. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- Waite, Mitchell; Lafore, Robert; Volpe, Jerry (1985). "Peripherals: Displays, Disk Drives, Printers, and More". The Official Book for the Commodore 128 Personal Computer. Howard W. Sams & Co. pp. 11–32. ISBN 0-672-22456-9.

- "Basic Commodore information".

- Anderson, Chris (June 1985). "On top of the US Goldmine". Zzap!64 (interview). pp. 46–48. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- Pountain, Dick (January 1985). "The Amstrad CPC 464". BYTE. pp. 401. Retrieved 27 October 2013.

- Halfhill, Tom (Dec 1983). "The Editor's Notes". Compute!'s Gazette (editorial). p. 6. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- Wagner, Roy (August 1986). "The Commodore Key". Computer Gaming World. p. 28. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- Brooks, M. Evan (November 1987). "Titans of the Computer Gaming World / MicroProse". Computer Gaming World. p. 16. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- Rupert, Dale (July 1987). "Rupert Report: Computers in Control". Ahoy!. New York: Ion International. p. 32. ISSN 8750-4383. Retrieved 2018-04-12.

- pinouts.ru - C64 Cassette pinout, 2012-01-15

- Commodore 64 Programmer's Reference Guide. West Chester: Commodore Business Machines. 1984. Commodore 64 Schematic Diagram. ISBN 0-672-22056-3. Retrieved 2018-04-12.

- SAMS Computerfacts CC4: Computer: Commodore 64. Indianapolis: Howard W. Sams. 1984. p. 2.

- "How Commodore tapes work". 091205 wav-prg.sourceforge.net

- Datasette service manual model C2N/1530/1531, preliminary, Oct. 1984 PN-314002-02

- http://www.zimmers.net/anonftp/pub/cbm/faq/trivia/cbm-trivia-13.txt

- Abril, Editora (26 October 1973). "Placar Magazine". Editora Abril. Retrieved 27 June 2017 – via Google Books.

- Bo Zimmerman. "Commodore Datasettes". Commodore Gallery. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- Thornburg, David D. (April 1981). "The Commodore VIC-20: A First Look". Compute!. p. 26.

- Butterfield, JIm (April 1981). "Advice to PET Owners: How To Be A VIC Expert". Compute!. No. 11. p. 34.

External links

- Similar Commodore tape drives

- Datasette photos

- Description of tape format with conversion utilities and code

- C2N232 project to build a hardware adaptor/software program to archive Commodore Datasette files to a modern computer.

- DC2N Homepage Digital C2N replacement project.

- Sketchup model of the Commodore Datasette 1530. Sketchup model of the Commodore Datasette 1530.