Co-operative economics

Co-operative economics is a field of economics that incorporates co-operative studies and political economy toward the study and management of co-operatives.[1]

| Part of a series on |

| Economics |

|---|

|

|

|

By application |

|

Notable economists |

|

Lists |

|

Glossary |

|

| This is part of a series on |

| Syndicalism |

|---|

|

|

Variants

|

|

Economics |

|

|

History

Notable theoreticians who have contributed to the field include Robert Owen,[2] Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Charles Gide,[3] Beatrice and Sydney Webb,[4] J.T.W. Mitchell, Peter Kropotkin,[5] Paul Lambart,[6] Race Mathews,[7] David Griffiths,[8] and G.D.H. Cole.[9] Additional theorists include John Stuart Mill, Laurence Gronlund, Leland Stanford,[10][11] and modern theoretical work by Benjamin Ward,[12] Jaroslav Vanek,[13] David Ellerman,[14] and Anne Milford[15] and Roger McCain.[16] Additional modern thinkers include Joyce Rothschild,[17] Jessica Gordon Nembhard,[18] Corey Rosen et al.,[19] William Foote Whyte,[20] Gar Alperovitz,[21] Seymour Melman,[22] Mario Bunge, Richard D. Wolff and David Schweickart.[23] In Europe, important contributions came from England and Italy, especially from Will Bartlett,[24] Virginie Perotin,[25] Bruno Jossa,[26] Stefano Zamagni,[27] Carlo Borzaga,[28] Jacques Defourny[29] and Tom Winters. [30]

Co-operative federalism versus co-operative individualism

A major historical debate in co-operative economics has been between co-operative federalism and co-operative individualism. In an Owenite village of cooperation or a commune, the residents would be both the producers and consumers of its products. However, for co-operative enterprise other than communes, the producers and consumers of its products are two different groups of people, and usually only one of these groups is given the status of members (or co-owners).

We can define two different modes of co-operative business enterprise: consumers' cooperative, in which the consumers of a co-operative's goods and services are defined as its members (including retail food co-operatives, credit unions, etc.), and worker cooperatives and producer co-operatives. In worker cooperatives, the producers or workers producing or marketing goods and services are organized into a co-op effort and are its members. Worker cooperatives are owned by their workers, for example by the owners of the farm, the cheese production, etc., wherever production is taking place. These farms are not required, and are rarely in actuality, owned by workers. (Some consider worker cooperatives, which are owned and run exclusively by their worker owners as a third class, others view this as part of the producer category.)

This in turn led to a debate between those who support consumer co-operatives (known as the Co-operative Federalists) and those who favor worker co-operatives (pejoratively labelled ‘Individualist' co-operativists by the Federalists[31] ).[32]

Co-operative federalism

Co-operative Federalism is the school of thought favouring consumer co-operative societies. Historically, its proponents have included JTW Mitchell and Charles Gide, as well as Paul Lambart and Beatrice Webb. The co-operative federalists argue that consumers should form co-operative wholesale societies (Co-operative Federations in which all members are co-operators, the best historical example of which being CWS in the United Kingdom), and that these co-operative wholesale societies should undertake purchasing farms or factories. They argue that profits (or surpluses) from these co-operative wholesale societies should be paid as dividends to the member co-operators, rather than to their workers.[33]

Co-operative Individualism

Co-operative Individualism is the school of thought favouring workers' co-operatives. The most notable proponents of workers' co-operatives being, in Britain, the Christian Socialists, and later writers like Joseph Reeves, who put this forth as a path to State Socialism.[34] Where the Co-operative Federalists argue for federations in which consumer co-operators federate, and receive the monetary dividends, rather, in co-operative wholesale societies the profits (or surpluses) would be paid as dividends to their workers.[33] The Mondragón Co-operatives are an economic model commonly cited by Co-operative Individualists, and a lot of the Co-operative Individualist literature deals with these societies. This one in Spain has drawn so much attention because in 2010 it was the seventh-largest corporation. It consists of about 250 different worker cooperative businesses. The business model they provide includes "extensive integration and solidarity with employees", worker involvement in policy and committees, a "transparent" wage system, and of course "full practice of democratic control".[35] These two schools of thought are not necessarily in opposition, and that hybrids of the two positions are possible.[33]

James Warbasse's work,[36] and more recently Johnston Birchall's,[37] provide perspectives on the breadth of co-operative development nationally and internationally. Benjamin Ward provided a formal treatment to begin an evaluation of "market syndicalism." Jaroslav Vanek wrote a comprehensive work in an attempt to address cooperativism in economic terms and a "labor-managed economy."[38] David Ellerman began by considering legal philosophic aspects of co-operatives, developing the "labor theory of property."[39] In 2007 he used the classical economic premise in formulating his argument deconstructing the myth of capital rights to ownership.[40] Anna Milford has constructed a detailed theoretical examination of co-operatives in controlled buyer markets (monopsony), and the implications for Fair Trade strategies.[41]

Other schools

Retailers' cooperatives

In addition to customer vs. worker ownership, retailers' cooperatives also utilize organizations of already constituted corporations as collective owners of the produce.

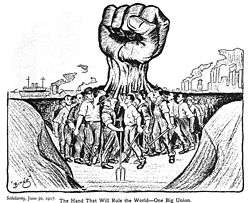

Socialism and left-wing anarchism

Socialists and left-anarchists, such as anarcho-communists and anarcho-syndicalists, view society as one big cooperative, and feel that goods produced by all should be distributed equitably to all members of the society, not necessarily through a market. All the members of a society are considered to be both producers and consumers. State socialists tend to favor government administration of the economy, while left-anarchists and libertarian socialists favor non-governmental coordination, either locally, or through labor unions and worker cooperatives. Although there is some debate as Bakunin and the collectivists favored market distribution using currency, collectivizing production, not consumption. Left libertarians collectivize neither but define their leftness as inalienable rights to the commons, not collective ownership of it, thus rejecting Lockean homesteading. See Centre for a stateless society

Utopian socialists feel socialism can be achieved without class struggle and that cooperatives should only include those who voluntarily choose to participate in them. Some participants in the kibbutz movement and other intentional communities fall into this category.

Co-operative commonwealth

In some Co-operative economics literature, the aim is the achievement of a Co-operative Commonwealth; a society based on cooperative and socialist principles. Co-operative economists - Federalist, Individualist, and otherwise - have presented the extension of their economic model to its natural limits as a goal.

This ideal was widely supported in early-twentieth century U.S. and Canadian leftist circles. This ideal, and the language behind it, were central to the formation of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation party in 1932, which became Canada's largest left-wing political party, and continues to this day as the New Democratic Party. They were also important to the economic principles of the Farmer-Labor Party of the United States, particularly in the FLP's Minnesota affiliate, where advocacy for a Co-operative Commonwealth formed the central theme of the Party's platform from 1934, until the Minnesota FLP merged with the state Democratic Party to form the Democratic–Farmer–Labor Party in 1944.

Co-operative Commonwealth ideas were also developed in Great Britain and Ireland from the 1880s by William Morris, which also inspired the guild socialist movement for associative democracy from 1906 right through the 1920s. Guild socialist thinkers included Bertrand Russell, R.H. Tawney and G.D.H. Cole.

Employee ownership

Some economists have argued that economic democracy could be achieved by combining employee ownership on a national scale (including worker cooperatives) within a free market apparatus. Tom Winters argues that "as with the free market more generally, it is not free trade itself that creates inequality, it’s how free trade is used, who benefits from it and who does not."[42]

Cooperative microeconomics

According to Hervé Moulin, cooperation from a game-theoretic point of view ("in the economic tradition") is the mutual assistance between egoists. He distinguishes three modes of such cooperation, which are easily remembered using the (incomplete) motto of the French Revolution:

- liberty: decentralised behaviour, where the collective outcome results from the strategic decisions of selfish agents;

- equality: arbitration (by a mechanical formula or benevolent dictator) about actions on the basis of normative principles;

- brotherhood: direct agreement between agents after face-to-face bargaining.

These modes are present in every cooperative institution but their virtues are often logically incompatible.[43]

See also

References

- "Cooperative Economics". Archived from the original on 2018-02-19. Retrieved 2017-06-17.

- Owen, Robert, "A New View of Society" (originally published in 1813/1814), in Gartrell, V.A. (ed.), "Report to the County of Lanark / A New View of Society", Ringwood: Penguin Books, 1970.

- Gide, Charles; as translated from French by the Co-operative Reference Library, Dublin, "Consumers' Co-Operative Societies", Manchester: The Co-Operative Union Limited, 1921

- Potter, Beatrice, "The Co-operative Movement in Great Britain", London: Swan Sonnenschein & Co., 1891.

- Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution (1902) (1998 paperback ed.). London: Freedom Press. ISBN 978-0-900384-36-3.

- Lambert, Paul; as translated by Létarges, Joseph; and Flanagan, D.; “Studies in the Social Philosophy of Co-operation”, (originally published March 1959), Manchester: Co-operative Union, Ltd., 1963.

- Mathews, Race, "Building the society of equals : worker co-operatives and the A.L.P.", Melbourne: Victorian Fabian Society, 1983.

- Charles, Graeme, and Griffiths, David, “The Co-operative Formation Decision: Discussing the Co-operative Option”, Frankston: Co-operative Federation of Victoria Ltd., 2003 and 2004

- Cole, G.D.H., “The British Co-operative Movement in a Socialist Society: A Report for the Fabian Society”, London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd., 1951., and Cole, G.D.H., “A Century of Co-operation”, Oxford: George Allen & Unwin for The Co-operative Union Ltd., 1944.

- Stanford, Leland, 1887. Co-operation of Labor, New York Tribune, May 4, 1887. Special Collection 33a, Box 7, Folder 74, Stanford University Archives. PDF

- Altenberg, Lee "Beyond Capitalism: Leland Stanford's Forgotten Vision," Sandstone and Tile, Vol. 14 (1): 8-20, Winter 1990, Stanford Historical Society, Stanford, California. http://dynamics.org/Altenberg/PAPERS/BCLSFV/, accessed June 20, 2016.

- Ward, B., “The Firm in Illyria: Market Syndicalism,” The American Economic Review, 48:4, 1958, 566-589.

- Vanek, J. The Participatory Economy: An Evolutionary Hypothesis and a Strategy for Development. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1971.

- Ellerman, D. (1992) Property and Contract in Economics: The Case for Economic Democracy.

- Milford, A. (2004) "Coffee, Cooperatives, and Competition." Chr. Michelsen Institute (at FLO)

- McCain, Roger (1977). "On the optimal financial environment for worker cooperatives". Zeitschrift für Nationalokonomie. 37 (3–4): 355–384. doi:10.1007/BF01291379.

- Rothschild, J., “Worker Cooperatives and Social Enterprise,” American Behavioral Scientist, 52:7, Mar. 2009, 1023-1041.

- Nembhard, J.G. and C. Haynes Jr., “Cooperative Economics- A Community Revitalization Strategy,” Review of Black Political Economics, Summer 1999, 47-71.

- Rosen, C. et al. (2005) Equity.

- Whyte, WF and KK Whyte, (1988) Making Mondragon

- Alperovitz, G. America Beyond Capitalism

- Melman, S. (2001) After Capitalism

- Schweickart, D. (2011) After Capitalism

- Bartlett, Will (1987). "Capital accumulation and employment in a self-financed worker cooperative". International Journal of Industrial Organization. 5 (3): 257–349.

- Pérotin, Virginie (2014). "Worker Cooperatives: Good, Sustainable Jobs in the Community" (PDF). Journal of Entrepreneurial and Organizational Diversity. 2 (2): 34–47.

- Jossa, Bruno (2012). "Cooperative Firms as a New Mode of Production". Review of Political Economy. 24 (3): 399–416. doi:10.1080/09538259.2012.701915.

- Zamagni, Stefano (2010). Cooperative Enterprise Facing the Challenge of Globalization. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. ISBN 9781848449749.

- Carlo Borzaga and Jacques Defourny (2003). The Emergence of Social Enterprise. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415339216.

- Defourny, Jacques (1983). "L'autofinancement des coopératives de travailleurs et la théorie économique". Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics. 54 (2): 201–224. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8292.1983.tb01869.x.

- Winters, Tom (2018) The Cooperative State: The Case for Employee Ownership on a National Scale. ISBN 978-1726628839,

- Lewis, p. 244.

- This analysis is based on a discussion by Gide, Charles; as translated from French by the Co-operative Reference Library, Dublin, "Consumers' CoOperative Societies", Manchester: The Cooperative Union Limited, 1921, pp. 192-203.

- This analysis is based on a discussion by Gide, Charles, pp. 192-203.

- Reeves, Joseph, “A Century of Rochdale Cooperation 1844-1944”, London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1944.

- Dunn, John (2014). "Cooperatives". In Rowe, Debra (ed.). Achieving Sustainability: Visions, Principles, and Practices. Macmillan Reference USA. 1 – via GALE.

- Warbasse, J. (1936) Cooperative Democracy

- Birchall, J. (1997) The International Co-operative Movement

- Vanek, J. (1970) General Theory of Labor-Managed Economies'.'

- Ellerman, D. (1989) The Democratic Worker-Owned Firm

- Ellerman, D. (2007) "On the Role of Capital in 'Capitalist' and Labor-Managed Firms," Review of Radical Political Economics

- Milford, A. (2004) "Coffee, Cooperatives, Competition: The Impact of Fair Trade," Chr Michelsen Institute

- Winters, Tom (2018) The Cooperative State: The Case for Employee Ownership on a National Scale. p.200. ISBN 978-1726628839,

- Moulin, Hervé (1995). Cooperative Microeconomics: a Game-Theoretic Introduction. Princeton, N.J. and Chichester, West Sussex: Princeton University Press. pp. 4, 5, 11. ISBN 0-691-03481-8.

Further reading

- Consumers' Co-operative Societies, by Charles Gide, 1922

- Co-operation 1921-1947, published monthly by The Co-operative League of America

- The History of Co-operation, by George Jacob Holyoake, 1908

- Cooperative Peace, by James Peter Warbasse, 1950

- Problems Of Cooperation, by James Peter Warbasse, 1941

- Why Co-ops? What Are They? How Do They Work? A pamphlet from the G.I. Roundtable series by Joseph G. Knapp, 1944

- Law of Cooperatives, by Legal Firm Stoel Rives, Seattle

- For All The People: Uncovering the Hidden History of Cooperation, Cooperative Movements, and Communalism in America, PM Press, by John Curl, 2009

- The Commons and Co-operative Commonwealth, Pat Conaty 2013

- The Cooperative State: The Case for Employee Ownership on a National Scale, by Tom Winters, 2018

- Commons Sense: Co-operative place making and the capturing of land value for 21st century Garden Cities, edited by Pat Conaty and Martin Large, 2013

- The Economics of Financial Cooperatives: Income Distribution, Political Economy and Regulation, by Amr Khafagy, 2019