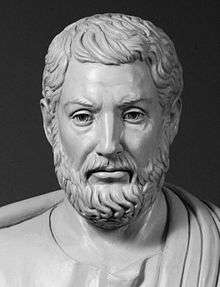

Cleisthenes

Cleisthenes (/ˈklaɪsθɪˌniːz/; Greek: Κλεισθένης, Kleisthénēs) was an ancient Athenian lawgiver credited with reforming the constitution of ancient Athens and setting it on a democratic footing in 508 BC.[1][2] For these accomplishments, historians refer to him as "the father of Athenian democracy."[3] He was a member of the aristocratic Alcmaeonid clan. He was the younger son of Megacles and Agariste making him the maternal grandson of the tyrant Cleisthenes of Sicyon. He was also credited with increasing the power of the Athenian citizens' assembly and for reducing the power of the nobility over Athenian politics.[4]

In 510 BC, Spartan troops helped the Athenians overthrow their king, the tyrant Hippias, son of Peisistratos. Cleomenes I, king of Sparta, put in place a pro-Spartan oligarchy headed by Isagoras. But his rival Cleisthenes, with the support of the middle class and aided by democrats, took over. Cleomenes intervened in 508 and 506 BC, but could not stop Cleisthenes, now supported by the Athenians. Through Cleisthenes' reforms, the people of Athens endowed their city with isonomic institutions—equal rights for all citizens (though only men were citizens)—and established ostracism.

Biography

Historians estimate that Cleisthenes was born around 570 BC.[5] Cleisthenes was the uncle of Pericles' mother Agariste[6] and of Alcibiades' maternal grandfather Megacles.[7]

Rise to power

With help from the Spartans and the Alcmaeonidae (Cleisthenes' genos, "clan"), he was responsible for overthrowing Hippias, the tyrant son of Pisistratus. After the collapse of Hippias' tyranny, Isagoras and Cleisthenes were rivals for power, but Isagoras won the upper hand by appealing to the Spartan king Cleomenes I to help him expel Cleisthenes. He did so on the pretext of the Alcmaeonid curse. Consequently, Cleisthenes left Athens as an exile, and Isagoras was unrivalled in power within the city. Isagoras set about dispossessing hundreds of Athenians of their homes and exiling them on the pretext that they too were cursed. He also attempted to dissolve the Boule (βουλή), a council of Athenian citizens appointed to run the daily affairs of the city. However, the council resisted, and the Athenian people declared their support of the council. Isagoras and his supporters were forced to flee to the Acropolis, remaining besieged there for two days. On the third day they fled the city and were banished. Cleisthenes was subsequently recalled, along with hundreds of exiles, and he assumed leadership of Athens.[8]

Contribution to the governance of Athens

After this victory, Cleisthenes began to reform the government of Athens. He commissioned a bronze memorial from the sculptor Antenor in honor of the lovers and tyrannicides Harmodius and Aristogeiton, whom Hippias had executed. In order to forestall strife between the traditional clans, which had led to the tyranny in the first place, he changed the political organization from the four traditional tribes, which were based on family relations and which formed the basis of the upper class Athenian political power network, into ten tribes according to their area of residence (their deme,) which would form the basis of a new democratic power structure.[9] It is thought that there may have been 139 demes (though this is still a matter of debate), each organized into three groups called trittyes ("thirds"), with ten demes divided among three regions in each trittyes (a city region, asty; a coastal region, paralia; and an inland region, mesogeia).[10] Cleisthenes also abolished patronymics in favour of demonymics (a name given according to the deme to which one belongs), thus increasing Athenians' sense of belonging to a deme.[10] He also established sortition - the random selection of citizens to fill government positions rather than kinship or heredity, a true test of real democracy. He reorganized the Boule, created with 400 members under Solon, so that it had 500 members, 50 from each tribe. He also introduced the bouletic oath, "To advise according to the laws what was best for the people".[11] The court system (Dikasteria — law courts) was reorganized and had from 201–5001 jurors selected each day, up to 500 from each tribe. It was the role of the Boule to propose laws to the assembly of voters, who convened in Athens around forty times a year for this purpose. The bills proposed could be rejected, passed or returned for amendments by the assembly.

Cleisthenes also may have introduced ostracism (first used in 487 BC), whereby a vote by a plurality of citizens would exile a citizen for 10 years. The initial trend was to vote for a citizen deemed a threat to the democracy (e.g., by having ambitions to set himself up as tyrant). However, soon after, any citizen judged to have too much power in the city tended to be targeted for exile (e.g., Xanthippus in 485/84 BC).[12] Under this system, the exiled man's property was maintained, but he was not physically in the city where he could possibly create a new tyranny. One later ancient author records that Cleisthenes himself was the first person to be ostracized.[13]

Cleisthenes called these reforms isonomia ("equality vis à vis law", iso-=equality; nomos=law), instead of demokratia. Cleisthenes' life after his reforms is unknown as no ancient texts mention him thereafter.

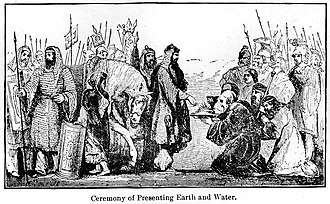

Attempt to obtain Persian support (507 BC)

In 507 BC, during the time Cleisthenes was leading Athenian politics, and probably at his instigation, democratic Athens sent an embassy to Artaphernes, brother of Darius I and Achaemenid Satrap of Asia Minor in the capital of Sardis, looking for Persian assistance in order to resist the threats from Sparta.[15][16] Herodotus reports that Artaphernes had no previous knowledge of the Athenians, and his initial reaction was "Who are these people?".[15] Artaphernes asked the Athenians for "Water and Earth", a symbol of submission, if they wanted help from the Achaemenid king.[16] The Athenian ambassadors apparently accepted to comply, and to give "Earth and Water".[15] Artaphernes also advised the Athenians that they should receive back the Athenian tyrant Hippias. The Persians threatened to attack Athens if they did not accept Hippias. Nevertheless, the Athenians preferred to remain democratic despite the danger from the Achaemenid Empire, and the ambassadors were disavowed and censured upon their return to Athens.[15]

After that, the Athenians sent to bring back Cleisthenes and the seven hundred households banished by Cleomenes; then they despatched envoys to Sardis, desiring to make an alliance with the Persians; for they knew that they had provoked the Lacedaemonians and Cleomenes to war. When the envoys came to Sardis and spoke as they had been bidden, Artaphrenes son of Hystaspes, viceroy of Sardis, asked them, "What men are you, and where dwell you, who desire alliance with the Persians?" Being informed by the envoys, he gave them an answer whereof the substance was, that if the Athenians gave king Darius earth and water, then he would make alliance with them; but if not, his command was that they should begone. The envoys consulted together and consented to give what was asked, in their desire to make the alliance. So they returned to their own country, and were then greatly blamed for what they had done.

— Herodotus 5.73.[14]

There is a possibility that the Achaemenid ruler now saw the Athenians as subjects who had solemnly promised submission through the gift of "Earth and Water", and that subsequent actions by the Athenians, such as their intervention in the Ionian revolt, were perceived as a break of oath, and a rebellion to the central authority of the Achaemenid ruler.[15]

Notes

- Ober, pp. 83 ff.

- The New York Times (30 October 2007) [1st pub:2004]. John W. Wright (ed.). The New York Times Guide to Essential Knowledge, Second Edition: A Desk Reference for the Curious Mind. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 628. ISBN 978-0-312-37659-8. Retrieved 31 January 2017.

- R. Po-chia Hsia, Julius Caesar, Thomas R. Martin, Barbara H. Rosenwein, and Bonnie G. Smith, The Making of the West, Peoples and Cultures, A Concise History, Volume I: To 1740 (Boston and New York: Bedford/St. Martin's, 2007), 44.

- Langer, William L. (1968) The Early Period, to c. 500 B.C. An Encyclopedia of World History (Fourth Edition pp. 66). Printed in the United States of America: Houghton Mifflin Company. Accessed: January 30, 2011

- The Greeks:Crucible of Civilization (2000)

- Herodotus, Histories 6.131

- Plutarch. Plutarch's Lives. with an English Translation by. Bernadotte Perrin. Cambridge, Massachusetts. Harvard University Press. London. William Heinemann Ltd. 1916. 4.

- Aristotle, Constitution of the Athenians, Chapter 20

- Aristotle, Politics 6.4.

- Aristotle, Constitution of the Athenians, Chapter 21

- Morris & Raaflaub Democracy 2500?: Questions and Challenges

- Aristotle, Constitution of the Athenians, Chapter 22

- Aelian, Varia historia 13.24

- LacusCurtius • Herodotus — Book V: Chapters 55‑96.

- Waters, Matt (2014). Ancient Persia: A Concise History of the Achaemenid Empire, 550–330 BCE. Cambridge University Press. pp. 84–85. ISBN 9781107009608.

- Waters, Matt (2014). Ancient Persia: A Concise History of the Achaemenid Empire, 550–330 BCE. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107009608.

References

Primary sources

- Aristotle. . Translated by Frederic George Kenyon – via Wikisource.. See original text in Perseus program.

- Aristotle (1984). The Athenian Constitution. P.J. Rhodes trans. Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-044431-9.

Secondary sources

- Morris I.; Raaflaub K., eds. (1998). Democracy 2500?: Questions and Challenges. Kendal/Hunt Publishing Co.

- Ober, Josiah (2007). "I Besieged That Man, Democracy's Revolutionary Start". Origins of Democracy in Ancient Greece. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24562-4.

- Lévêque, Pierre; Vidal-Naquet, Pierre (1996). Cleisthenes the Athenian: An Essay on the Representation of Space and Time in Greek Political Thought from the End of the Sixth Century to the Death of Plato. Humanities Press.

- David Ames Curtis: Translator's Foreword to Pierre Vidal-Maquet and Pierre Lévêque's Cleisthenes the Athenian: An Essay on the Representation of Space and Time in Greek Thought from the End of the Sixth Century to the Death of Plato (1993-1994) http://kaloskaisophos.org/rt/rtdac/rtdactf/rtdactfcleisthenes.html

| Library resources about Cleisthenes |

Further reading

- Davies, J.K. (1993). Democracy and classical Greece. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-19607-4.

- Ehrenberg, Victor (2010). From Solon to Socrates Greek History and Civilization During the 6th and 5th Centuries BC. Hoboken: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-203-84477-9.

- Forrest, William G. (1966). The Emergence of Greek Democracy, 800–400 BC. New York: McGraw–Hill.

- Hignett, Charles (1952). A History of the Athenian Constitution to the End of the Fifth Century BC. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Larsen, Jakob A. O. (1948). "Cleisthenes and the Development of the Theory of Democracy at Athens". In Konvitz, Milton R.; Murphy, Arthur E (eds.). Essays in Political Theory Presented to George H. Sabine. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- O'Neil, James L. (1995). The origins and development of ancient Greek democracy. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0-8476-7956-X.

- Staveley, E. S. (1972). Greek and Roman voting and elections. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell Univ. Pr. ISBN 0-8014-0693-5.

- Thorley, John (1996). Athenian democracy. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-12967-2.

- Zimmern, Alfred (1911). The Greek Commonwealth: Politics and Economics in Fifth Century Athens. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

External links

- BBC – History – The Democratic Experiment

| Preceded by Hippias |

Tyrant of Athens | Succeeded by Isagoras |

| Preceded by Isagoras |

Archon in the Athenian democracy | Succeeded by |