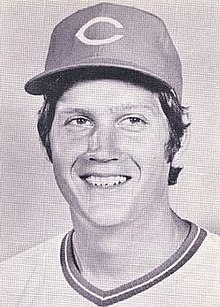

Clay Kirby

Clayton Laws Kirby, Jr. (June 25, 1948 – October 11, 1991) was a Major League Baseball (MLB) pitcher for the San Diego Padres (1969–73), Cincinnati Reds (1974–75) and Montreal Expos (1976).

| Clay Kirby | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Pitcher | |||

| Born: June 25, 1948 Washington, D.C. | |||

| Died: October 11, 1991 (aged 43) Arlington, Virginia | |||

| |||

| MLB debut | |||

| April 11, 1969, for the San Diego Padres | |||

| Last MLB appearance | |||

| September 28, 1976, for the Montreal Expos | |||

| MLB statistics | |||

| Win–loss record | 75–104 | ||

| Earned run average | 3.84 | ||

| Strikeouts | 1,061 | ||

| Teams | |||

| Career highlights and awards | |||

| |||

Early life

Clayton Laws "Clay" Kirby, Jr, was born in Washington, D.C. and attended Washington-Lee High School in Arlington, Virginia.[1] He was drafted by the St. Louis Cardinals in the third round of the 1966 draft, however, in October 1968 he was chosen in the expansion draft by the Padres, who would begin play in 1969 along with the Expos.[2]

MLB

He made his Major League debut at age 20 with the first-year Padres on April 11, 1969 as the Padres fell at home 8-0 to the San Francisco Giants. The first major league hitter he ever faced was Willie Mays, who walked, as Kirby gave up three earned runs in four innings.[3] Although he led the National League in losses that year with 20 (and seven wins), he had a 3.80 earned run average in 35 starts with 215.1 innings pitched.[2]

Near no-hitter

On July 21, 1970, Kirby was working on a no-hitter against the New York Mets after eight innings, but trailed 1-0 as the Mets scored in the first inning after a walk to Tommie Agee. Agee stole second base. Bud Harrelson popped up to the shortstop. Then Kirby walked Ken Singleton and the Mets pulled off a double steal. Agee was now on third, Singleton was on second and Art Shamsky was the batter. He hit a ground ball to second baseman Ron Slocum, who threw him out as Agee scored.[4] With two outs, Manager Preston Gómez had Cito Gaston pinch-hit for him in the bottom of the eighth, denying him a chance to complete the no-hitter. The 10,373 fans in attendance booed long and loud. Relief pitcher Jack Baldschun then gave up two runs and three hits in the ninth. Mets Jim McAndrew had retired 15 batters in a row en route to what would be a three-hit, 3-0 victory for the Mets. According to Mets pitcher Tom Seaver. “The Mets bench just gasped in disbelief,” Seaver told sportswriter Joe Durso. "I personally would have let him hit. If the pennant race were involved, no. But in this situation, yes.”[5][6] That season, Kirby posted a 10-16 record with a 4.53 ERA. The next two years Kirby had numbers of 15-13, 2.83 (with 13 complete games) in 1971 and 12-14, 3.13 in 1972. In 1973 his record fell to 8-18 with a 4.79 ERA.[2]

The Padres, who began play in 1969, remain the only Major League Baseball team never to have thrown a no-hitter. Fans and writers occasionally attribute this unlikely failure to the "Curse of Clay Kirby," in recognition of the controversial decision to remove Kirby from the game.[7][8]

Big Red Machine

In November 1973 Kirby was traded to the Reds for outfielder Bobby Tolan and the move paid off as Kirby went 12-9 with an ERA of 3.28 as the Reds won 98 games. In 1975, Kirby was one of six starters to win 10 or more games for the Big Red Machine, who won the National League title as he went 10-6 with an ERA of 4.72 in 19 starts. The Reds later won the 1975 World Series, but Kirby did not play in the series.[9]

He was sent to the Montreal Expos for Bob Bailey on December 12, 1975.[10] In January 1976 Kirby was stricken with a long bout of pneumonia before he joined the Expos in Florida for spring training. He was still weak and had a sore shoulder when the season opened. He got off to a miserable start and never recovered and in the 1976 season he fell to 1-8 with an ERA of 5.72, and it was his final major league season. Montreal released him on December 2, 1976. In January 1977 the Padres picked up their former pitcher to give him another chance. They invited him to their spring-training camp in Yuma, Arizona. A knee injury in the final week of spring training delayed his comeback try for almost two months. The Padres placed him in their Pacific Coast League farm club in Hawaii. He won his first game for the Islanders on June 18, but never won another. According to teammate John D'Acquisto in his book Fastball John, "Game after game, I would see him step off the mound in despair, unable to do what he had done all through high school and through much of his time at the major league level: pitch competitive baseball." His record for the season was one win, seven losses, and an earned-run average of 7.95.

After San Diego gave up on Kirby, he tried out with the Minnesota Twins during spring training in 1978. He lasted only two weeks before he was released. Kirby was out of Organized Baseball before his 30th birthday.

In his eight seasons in the Major Leagues, Kirby played 261 games (239 started) and had a 75–104 record with a 3.84 ERA, 42 complete games, eight shutouts, 1,548 innings pitched and 1,061 strikeouts.[2]

After baseball

Following his baseball career, Kirby was acting tournament chairman for the annual Major League Baseball Players Alumni (MLBPA) Washington Metropolitan Area Charity Golf Tournament. The event, which benefited the American Lung Association, was part of the "Swing With the Legends Golf Series."[1] His family continued to live in San Diego County until 1983, when they returned to Virginia. Kirby became a self-employed financial securities broker.

Death

On July 19, 1991, Kirby underwent a coronary atherectomy to open a blockage in an artery just above his heart. After the procedure he was told he had suffered a silent heart attack. Kirby had been complaining about chest discomfort and numbness in his arm. He died of a heart attack on October 11, 1991, at the age of 43. His wife found him about 11 o’clock in the morning in his chair. It appeared that he had fallen asleep while reading and suffered the fatal attack. He was survived by his wife, Susan; his mother, Gloria; his sister, Carolyn Twyman; his son, Clayton; his daughter, Theresa Schoengold; and two grandchildren, Derek and Brandon Schoengold. He was buried in the National Memorial Park in Falls Church, Virginia.

References

- Top 100: Clay Kirby, Washington-Lee Baseball, 1966 | The Connection Newspapers

- Clay Kirby Statistics and History - Baseball-Reference.com

- April 11, 1969 San Francisco Giants at San Diego Padres Box Score and Play by Play - Baseball-Reference.com

- July 21, 1970 New York Mets at San Diego Padres Play by Play and Box Score - Baseball-Reference.com

- PADRES: Forty years after the infamous Clay Kirby game, the no-hitter drought lives on Page 1 of 4 | UTSanDiego.com

- http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/24be38aa

- Lammers, Dirk. Baseball's One-Hit Wonders: More Than a Century of Pitching's Greatest Feats. Unbridled Books. 2016.

- Kenney, Kirk. "Padres streak approaches 7,500 games with no no-no." San Diego Union-Tribune. April 14, 2016.

- Durso Joseph. "Mets Trade Staub to Tigers for Lolich," The New York Times, Saturday, December 13, 1975. Retrieved May 1, 2020

External links

- Career statistics and player information from MLB, or Baseball-Reference, or Fangraphs, or Baseball-Reference (Minors)