Clarke brothers

Brothers Thomas (c. 1840 – 25 June 1867) and John Clarke (c. 1846 – 25 June 1867) were Australian bushrangers from the Braidwood district of New South Wales. They committed a series of high-profile crimes which led to the enacting of the Felons' Apprehension Act (1866), a law that introduced the concept of outlawry in the colony and authorised citizens to kill bushrangers on sight.[1]

Active in the southern goldfields from 1865 until their capture, Thomas and John were joined for a time by their brother James and several associates. They were responsible for a reported 71 robberies and hold-ups, as well as the death of at least one policeman; they are also suspected of killing a squad of four policemen looking to bring them in. The Clarkes also murdered one of their own gang members and a man they wrongly assumed was a police tracker, and shot several other victims. They were captured during a shoot-out in April 1867 and hanged two months later at Sydney's Darlinghurst Gaol. Their execution ended organised gang bushranging in New South Wales.

Some modern-day writers have described the Clarkes as the most bloodthirsty bushrangers of all, and according to one journalist, "Their crimes were so shocking that they never made their way into bushranger folklore — people just wanted to forget about them."[2]

Bushranging

The Clarkes' father Jack, a shoemaker transported to Sydney in 1828 for seven years aboard the Morley, arrived in the Braidwood district as a convict assigned to a pastoralist. He married Mary Connell and took up a leasehold in the Jingeras, which proved too small to support his family of five children. He took to selling sly-grog, initiated his sons Tom and John into cattle duffing, and raised them to believe in his view of the fair and equitable distribution of property. They constantly raided crops and livestock, aided by their uncles Pat and Tom Connell. Their gang, the Jerrabat Gully Rakers, were regarded as scientists in the art of cattle duffing and horse stealing. The Clarke gang of relatives and friends were well trained in bushcraft and heavily armed.

They plundered publicans, storekeepers, farmers and travelers. They ambushed gold shipments from Nerrigundah and Araluen and the coaches that traveled from Sydney and the Illawarra. Till November 1866 they marauded virtually unchecked in a triangle through the Jingeras from Braidwood to Bega, and up the coast to Moruya and Nelligen.

On 9 January 1867, a party of special constables—John Carroll, Patrick Kennagh, Eneas McDonnell and John Phegan—were ambushed and killed near Jinden Station. They had been tied to a tree and then shot. The Clarke brothers were implicated in the murders. A blood-soaked pound note was pinned to Carroll, the leader, as a warning to anyone else intent on pursuing them.

Their run of luck ended with the conviction at Darlinghurst on 15 February 1867 of Tom Connell for the robbery and assault of John Emmott, when he stole 25 ounces of gold dust, two one-pound notes, some silver coins and a gold watch. The many other exploits of the "Blacksmith", including the death of Constable Miles O'Grady were ignored, but his death sentence was on appeal remitted to life imprisonment. In February 1867 Long Jim "Jemmy the Warrigal", a second member of the gang, fractured his skull in an accident and died.

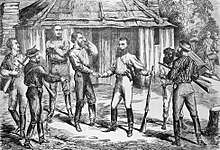

In late March 1867 the drought broke with floods which swept away steam engines, huts and mountains of earth. The remains of Billy Scott believed to have been murdered by his own gang, were found on 9 April, thus reducing the gang to two men, Tom and John Clarke. During April a police patrol led by Senior Constable Wright and an Aboriginal tracker Sir Watkin Wynne (later Sergeant Major Sir Watkin Wynne), followed information to Jinden Creek, and reached Berry's hut on Friday 26 April. The bushrangers and police engaged in a shoot-out that Saturday morning, during which John was shot in the right shoulder, and a plain clothes policeman received a gunshot graze. Wynne also received injuries during the fight. Senior Constable Walsh called for the bushrangers to surrender, and eventually they agreed. The reward for Tom Clarke had by then been raised to 1,000 pounds and that for John to 500 pounds.

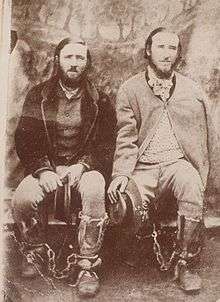

After their surrender, the brothers shook hands with the police, and were arraigned in Braidwood before being taken by coach to the port of Nelligen, where they were shackled to the prison tree. From there they were conveyed to Sydney. On 13 May they appeared in court for their committal hearing, on wounding Wynne, prior to their capture by Wright, Walsh, Egan and Lenehan. The £1500 reward was distributed as follows: Wright £300; Walsh £130; Wynne £120; constables Lenehan, Wright and Egan £110 each; sergeant Byrne £30; constables Ford, O'Loughlin, Armstrong, Brown and Woodlands £15 each; and £7 10s each to trackers Emmott and Thomas. £500 went to a civilian informer (the highest reward offered until the £2000 for Ned Kelly).

Trial and execution

The Clarkes' trial on 28 May 1867 lasted just a day. Chief Justice of New South Wales Sir Alfred Stephen was known to be especially concerned about bushranging, in particular Frank Gardiner, and had most to do with the drafting of the "Felons' Apprehension Act".

It was stated in evidence that "when Thomas Clarke fired, John Clarke fired immediately afterwards ... with the intent to kill and wound the constables...".

The jury took 67 minutes to find both brothers guilty. Before passing sentence, Stephen pointed out that the Clarkes were to be hanged, not as retribution, but because their deaths were necessary for the peace, good order, safety and welfare of society. Their fate was to serve as a warning to others. Stephen then pointed out the list of their offences over the previous two years. Thomas: exclusive of the seven murders of which he was suspected, including that of Constable O'Grady, 9 robberies of mails, 36 robberies of individuals including Chinamen, labourers, publicans, storekeepers, tradesmen and settlers, John's offences in one year numbered 26 and his possible implication in the unexplained murder of the four specials. On 13 March 1865, the Araluen Gold Escort was attacked by the gang on the Majors Creek Mountain Road, where two troopers were wounded. The four trooper escorts held off the attack and the gold was delivered to the Bank of New South Wales at Braidwood. Although this attack was carried out by Ben Hall, John Gilbert and John Dunn there was speculation in newspapers of the time that one of the Clarke brothers was the fourth member of the gang in this attack. However, it was mostly Daniel Ryan from Murruburrah and good friend of John Dunn. Ryan was later arrested as a suspect. The Araluen Escort Attack was dramatised in the 2016 film, The Legend of Ben Hall.

Following the death sentences, an appeal was made on a point of law. Because of the small number of Supreme Court Justices, the court of appeal was made up of Sir Alfred Stephen the Chief Justice, and Justices John Hargrave and Alfred Cheeke. The rejection of a new trial by two to one led many to believe that the conviction of the Clarkes was not altogether satisfactory. A memorandum was sent to the Governor, Sir John Young and the Executive Council. In the end, neither the Governor nor the ministry decided to interfere with the sentence imposed on either of the Clarkes. They were visited by their two sisters, their brother Jack (brought in from Cockatoo Island Prison), and their uncle Mick Connell (in gaol in Sydney awaiting his trial as one of their harbourers under the "Felons’ Apprehension Act" for supplying food, gin and ammunition to the bushrangers in October 1866 as evidenced by his brother's 20-year-old pregnant lover, Lucy Hurley).

Tom Clarke, 27, and his brother John, 21, were hanged from twin gallows at Darlinghurst Jail on 25 June 1867, ending a reign of terror on the south coast of New South Wales which had cost the lives of at least eight men who were mainly police trying to capture the brothers. The Clarkes and other bushrangers may have had some influence in Parkes's campaign for educational reforms. In his electioneering speeches of 1867 he spoke of the Clarkes and the necessity of schools in the outback as a way of putting down bushranging. "The Clarkes and other executed bushrangers were in large measure the victims of circumstances. The eyes of the children of the bush opened upon wild, savage scenery. They grew up creatures of a warm, passionate nature, without knowledge and respect for the law of the land and without any bonds to bind them to the rest of society. We want the means of instructing the young so they shall form an honest and intelligent generation when we shall have passed away". Subsequently, an attempt was made in the Braidwood district to improve the opportunities for education.

References

- Eburn, Michael (2005). "Outlawry in Colonial Australia: The Felons Apprehension Acts 1865-1899" (PDF). Australian and New Zealand Law and History E-Journal. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 October 2008. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- Brown, Bill (10 April 2017). "Re-enactment to look back at capture of Australia's deadliest bushrangers at Braidwood". ABC News. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- Fitzgerald, A. (1977). Historic Canberra 1825-1945, a pictorial record. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service. ISBN 0-642-02688-2.

External links

- "The Clarke Brothers". About NSW. Archived from the original on 28 May 2011.

- Phillips, Nan. "Clarke, John (1846-1867)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Retrieved 9 July 2011.