Civilian Public Service

The Civilian Public Service (CPS) was a program of the United States government that provided conscientious objectors with an alternative to military service during World War II. From 1941 to 1947, nearly 12,000 draftees, willing to serve their country in some capacity but unwilling to perform any type of military service, accepted assignments in work of national importance in 152 CPS camps throughout the United States and Puerto Rico. Draftees from the historic peace churches and other faiths worked in areas such as soil conservation, forestry, fire fighting, agriculture, under the supervision of such agencies as the U.S. Forest Service, the Soil Conservation Service, and the National Park Service. Others helped provide social services and mental health services.

The CPS men served without wages and minimal support from the federal government. The cost of maintaining the CPS camps and providing for the needs of the men was the responsibility of their congregations and families. CPS men served longer than regular draftees and were not released until well after the end of the war. Initially skeptical of the program, government agencies learned to appreciate the men's service and requested more workers from the program. CPS made significant contributions to forest fire prevention, erosion and flood control, medical science and reform of the mental health system.

Background

Conscientious objectors (COs) refuse to participate in military service because of belief or religious training. During wartime, this stance conflicts with conscription efforts. Those willing to accept non-combatant roles, such as medical personnel, are accommodated. There are few legal options for draftees who cannot cooperate with the military in any way.

Experiences of World War I

The conscription law of World War I provided for noncombatant service for members of a religious organization whose members were forbidden from participating in war of any form.[2] This exemption effectively limited conscientious objector status to members of the historic peace churches: Mennonites (and other Anabaptist groups such as Hutterites), Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) and Church of the Brethren. The law gave the President authority to assign such draftees to any noncombatant military role.

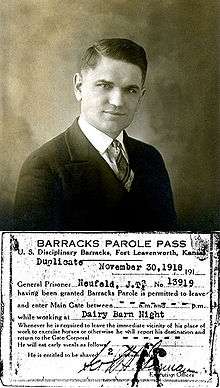

Conscientious objectors who refused noncombatant service during World War I were imprisoned in military facilities such as Fort Lewis (Washington), Alcatraz Island (California) and Fort Leavenworth (Kansas). The government assumed that COs could be converted into soldiers once they were exposed to life in their assigned military camps. Simultaneously the Justice Department was preparing to indict 181 Mennonite leaders for violating the espionage act because of a statement they adopted against performing military service.[3] The draftees' refusal to put on a uniform or cooperate in any way caused difficulties for both the government and the COs. The treatment received by nearly 2,000[4] of these absolute COs included short rations, solitary confinement and physical abuse so severe as to cause the deaths of two Hutterite draftees.[5]

Preparation for World War II

After World War I, and with another European war looming, leaders from the historic peace churches met to strategize about how to cooperate with the government to avoid the difficulties of World War I. Holding a common view that any participation in military service was not acceptable, they devised a plan of civilian alternative service, based on experience gained by American Friends Service Committee work in Europe during and after World War I and forestry service done by Russian Mennonites in lieu of military service in Tsarist Russia.[6]

As the United States prepared for another war, the historic peace churches, represented by Friends who understood inner dealings of Washington D.C. politics, attempted to influence new draft bills to ensure their men could fulfill their duty in an alternative, non-military type of service. On June 20, 1940, the Burke-Wadsworth Bill came before Congress. The arrangements for conscientious objectors were almost identical to the World War I provisions.[7]

Selective Service Act

The Friends representatives continued attempting to make the bill more favorable to the historic peace churches. The Burke-Wadsworth Bill passed on September 14, 1940, becoming the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940. The influence of the churches was evident in section 5(g), which says in part:

Any such person claiming such exemption from combatant training and service ... in lieu of such induction, be assigned to work of national importance under civilian direction.[8]

The bill offered four improvements from the perspective of the churches over the World War I provisions.[9] The exemption applied to conscientious objection based on religious training or belief, opening the door for members of any religious denomination to apply for CO status. Draftees turned down by local draft board could appeal under the new law. Those assigned to "work of national importance" would be under civilian, not military, control and violations of law on the part of those in the program were subject to normal federal jurisdiction, not the military justice system. From the military perspective, it removed the burden of dealing with thousands of uncooperative draftees and segregated the COs and their philosophy from military service members.

Unlike harsher methods, the military found that this gentler approach resulted in about one in eight eventually transferring to military service.

Organization

When registration commenced on October 16, 1940, no structure was in place to handle thousands of anticipated conscientious objectors. Church representatives meeting with government officials learned that little thought had been put into the program, and the churches were advised to create a plan.[10] Because the government wanted to deal with one body, not individual religious denominations, the National Council for Religious Conscientious Objectors was formed as a liaison between the churches and the federal government. The historic peace churches outlined a plan that included running and maintaining CPS camps under church control. However, President Roosevelt opposed any plan not involving military control over the draftees.[11] To save their plan and retain civilian direction of the program, the churches offered to fund the camps. Aides convinced Roosevelt that putting the COs to work in out-of-the-way camps was preferable to repeating the difficulties of World War I. Selective Service and the peace churches agreed to a six-month trial of church supported and funded camps for conscientious objectors and thus Civilian Public Service was born.

The first camp opened on May 15, 1941 near Baltimore, Maryland. A total of 152 camps and units[12] were established over the next six years. The federal government provided work projects, housing, camp furnishings and paid for transportation to the camps. The responsibilities of the churches included day-to-day management of the camps, subsistence costs, meals and healthcare for the men.[13] When the young men arrived at the first camps, they started a six-month experiment that would extend to six years.

Camp life

| Religious Affiliation | |

|---|---|

| Number | Affiliation[14] |

| 223 | Baptist |

| 127 | Christadelphian |

| 1,353 | Church of the Brethren |

| 78 | Church of Christ |

| 209 | Congregational Church |

| 78 | Disciples of Christ |

| 88 | Episcopal |

| 50 | Evangelical |

| 101 | Evangelical and Reformed |

| 157 | German Baptist Brethren |

| 409 | Jehovah's Witnesses |

| 108 | Lutheran |

| 4,665 | Mennonite[15] |

| 673 | Methodist |

| 192 | Presbyterian |

| 951 | Religious Society of Friends |

| 149 | Roman Catholic |

| 76 | Russian Molokans |

| 44 | Unitarians |

| 1,695 | Other religious groups |

| 449 | Unaffiliated |

| 11,996 | Total |

Civilian Public Service men lived in barracks-style camps, such as former Civilian Conservation Corps facilities. The camps served as a base of operations, from which the COs departed to their daily assignments. Sites were located typically in rural areas near the agricultural, soil conservation and forestry projects where the work took place. A large camp such as number 57 near Hill City, South Dakota, had five dormitories and housed as many as 172 men building the Deerfield Dam.[16] Later, with projects located in urban areas, the men lived in smaller units, communal housing near their assignments. CPS men typically worked nine hours, six days per week.

Mennonite Central Committee, American Friends Service Committee and Brethren Service Committee administered almost all of the camps.[17] The Association of Catholic Conscientious Objectors managed four camps and the Methodist World Peace Commission two. Each camp was assigned a director responsible for supervising camp operation. The director managed the needs of the men, oversaw maintenance of the camp facilities, handled community relations and reported to Selective Service officials. Initially a pastor had the camp director role. Later, capable men from among the CPS workers directed the camps.

Besides the director, a matron, business manager and dietitian staffed a typical camp. An educational director was responsible for creating recreational, social and educational programs for the men. Church history, Bible and first aid were standard course topics. The strength of instructional programs varied from camp to camp, and after nine hours of physical labor, it could be difficult to motivate the men to attend classes. Most camps had libraries, some showed current films and camp number 56 (Camp Angel) near Waldport, Oregon had a particular emphasis on the arts. Camps produced newsletters and yearbooks documenting their experiences.[18]

The camp dietitian, with the help of men assigned as cooks, prepared all of the meals. Camps with large gardens provided their own fresh vegetables. Sponsoring congregations also supplied home canned and fresh produce. The camps were subject to the same shortages and rationing as the rest of the nation.[19]

Sunday worship services were organized by the camp director if he was a pastor, by a visiting pastor, or by the CPS men themselves. While the historic peace churches organized the CPS, 38% of the men came from other denominations and 4% claimed no religious affiliation.[20]

Men spent their free time doing crafts such as woodworking, rugmaking, leatherwork and photography. Outdoor activities included hiking and swimming. Men formed choirs and music ensembles, performing in neighboring towns when relations were good.[21] The men earned two days of furlough for each month of service. These days could be saved to allow enough time to travel several hundred miles home or in some cases traded to other men in exchange for cash.

Men with wives and dependents found it difficult to support their families. Beyond a small allowance, the men did not get paid for their service, nor were their dependents given an allowance.[22] To be closer to their husbands, women sought employment near their husband's assignment. Later, when jobs on dairy farms became available, families could live together in housing provided for farm workers.

Men who became uncooperative with the CPS system and were unable to adjust to the church-managed camps were reassigned to a few camps managed by the Selective Service System.[23] These camps tended to be the least productive and most difficult to administer. Men who felt compelled to protest the restrictions of the conscription law attempted to disrupt the program through the use of various techniques, including the initiation of work slowdowns and labor strikes. Routine rule breaking frustrated camp directors. The most difficult cases were given to the federal court system and the men imprisoned.[24]

Finances

Churches were primarily responsible for financing Civilian Public Service, providing for the men's food, clothes, and other material needs. The churches also provided and paid for the camp director. To cover personal needs, the men received a monthly allowance of between $2.50 and $5.00 (equivalent to $43 and $87 respectively in 2019). When jobs were available in surrounding farms and communities, those willing to work beyond their regular CPS jobs could earn extra spending money. The federal government spent $1.3 million on the CPS program.[25] The men performed $6 million of unpaid labor in return.

Men who worked for farmers or psychiatric hospitals received regular wages, which they were required to give to the federal government.[26] Objections to this practice developed immediately because the men felt they were helping to fund the war. A compromise was reached where the wages were put into a special fund that was unused until after the end of the war. At one point, church representatives attempted unsuccessfully to have these funds used for providing a living allowance for the men's dependents.[27]

Types of work

The first Civilian Public Service projects were in rural areas where the men performed tasks related to soil conservation, agriculture and forestry. Later men were assigned to projects in cities where they worked in hospitals, psychiatric wards, and university research centers.

Soil conservation and agriculture

Anticipating the rural background of most men, the initial camps provided soil conservation and farming-related projects. By August 1945, 550 men worked on dairy farms and with milk testing.[28] Labor-intensive farming operations like dairies were short of workers and accepted COs to help fill the gap. Men assigned to the Bureau of Reclamation built contours to prevent soil erosion, constructed 164 reservoirs and 249 dams. A sixth of all CPS work was performed in this area.[29]

Forestry and National Parks

At Forest Service and National Park Service camps, CPS men were responsible for fire control. Between fires they built forest trails, cared for nursery stock, planted thousands of seedlings and engaged in pest control. Campgrounds and roadways on the Blue Ridge Parkway and Skyline Drive of Virginia are products of CPS labor.[29]

Hundreds of men volunteered for smoke jumping, showing their willingness to take great personal risks. When fire was detected by a lookout, smoke jumpers were flown directly to the site and dropped by parachute to quickly contain and extinguish the fire. From base camps scattered through the forests of Montana, Idaho and Oregon, the men were flown as many as 200 miles to fire sites, carrying firefighting tools and a two-day supply of K-rations. For larger fires, additional men, supplies and food were airdropped to expand the effort. Up to 240 CPS men served in this specialized program.[30] One of the smokejumping schools was at Camp Paxson in Montana.[31]

Mental health

As the war progressed, a critical shortage of workers in psychiatric hospitals developed, because staff had left for better paying jobs with fewer hours and improved working conditions. Understaffed wards at Philadelphia State Hospital had one attendant member for 300 patients,[32] the minimum ratio being 10:1. The government balked at initial requests that CPS workers have these positions, believing it better to keep the men segregated in the rural camps to prevent the spread of their philosophy.

Eventually the men received permission to work for the mental institutions as attendants or psychiatric aides. Individuals who found jobs at the rural camps unfulfilling and meaningless volunteered for this new type of assignment. The mental health field promised to provide the work of national importance that the program was designed to produce. By the end of 1945, more than 2000 CPS men worked in 41 institutions in 20 states.[33]

The CPS men discovered appalling conditions in the mental hospital wards. In an interview, a conscientious objector described his experience when he first entered a mental hospital in October 1942:[34]

It is sort of like a perpetual bad dream. The smells, the sounds of the insane voices, the bad equipment. The long, dark corridors. I tell you, it is all very much like a medieval fairytale of the nether regions. We’d heard about how these patients had been treated by the attendants, Beat with rods, you know, do all kind of things. We took a vow before we left the camp, we decided that we would not assault or in any way, strike a patient. I opened one of those rooms, and there was a man lying on the floor. I leaned over to try to see what I could do to minister to him in some way, do something for him. He may have been on a mattress or he may have been on the bare floor. No he was on the bare floor, because when I tried to move him, his skin came off. His skin was bloody and stuck to the floor and when I tried to lift him up it just peeled his skin off. He was in the last stages of syphilis. He died less than a week afterwards. Now that was my first introduction to what was badly needed in that institution.

The CPS men objected to the mistreatment and abuse of patients and determined to improve conditions in the psychiatric wards. They wanted to show other attendants alternatives to violence when dealing with patients.

Frank Olmstead, chairman of the War Resisters League observed:[35]

One objector assigned to a violent ward refused to take the broomstick offered by the Charge. When he entered the ward the patients crowded around asking, "Where is your broomstick?" He said he thought he would not need it. "But suppose some of us gang up on you?" The CO guessed they wouldn't do that and started talking about other things. Within a few days the patients were seen gathering around the unarmed attendant telling him of their troubles. He felt much safer than the Charge who had only his broomstick for company.

Outraged workers surveyed CPS men in other hospitals and learned of the degree of abuse throughout the psychiatric care system. Contacting church managers and government officials, the COs begin advocating for reforms to end the abuses. Conditions were exposed in institutions such as Cleveland State Hospital, Eastern State Hospital in Virginia and Hudson River State Hospital.[36] One explained:[34]

And the governor came in and they cleaned out the hospital. I mean, they had hearings. We all had to appear in court and all that kind of stuff. And within a month or so, the hospital was completely changed. The superintendent was fired and the new superintendent was put in, and not only did they do our hospital, they did all the hospitals, mental hospitals in Virginia.

The reformers were especially active at the Byberry Hospital in Philadelphia where four Friends initiated The Attendant magazine as a way to communicate ideas and promote reform. This periodical later became The Psychiatric Aide, a professional journal for mental health workers. On May 6, 1946 Life Magazine printed an exposé of the mental healthcare system based on the reports of COs. Another effort of CPS, Mental Hygiene Project became the National Mental Health Foundation.[37] Initially skeptical about the value of Civilian Public Service, Eleanor Roosevelt, impressed by the changes introduced by COs in the mental health system, became a sponsor of the National Mental Health Foundation and actively inspired other prominent citizens including Owen J. Roberts, Pearl Buck and Harry Emerson Fosdick to join her in advancing the organization's objectives of reform and humane treatment of patients.[38]

Medical experiments

A faction of the Civilian Public Service camps developed into a scientific research unit known as Camp #115, or the “Guinea pig units.”[39] These units included around 500 conscientious objectors who volunteered to be scientific test subjects in a wide range of human medical experiments in the country’s top universities and hospitals.[40] The majority of these experiments were conducted under the direction and approval of the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD), the Committee on Medical Research (CMR), and the Surgeon General at leading academic and medical institutions such as Harvard Medical School, Yale and Stanford Universities, and Massachusetts General Hospital. These experiments involved a range of research topics, including studying disease, survival in extreme conditions, and equipment testing. The experiments often endangered the health of the COs.[41][42]

The following chart lists the unit numbers, facility, type of project, capacity of CPS assignees, and dates of many experiments done on COs that were approved by the OSRD and CMR as reported by Selective Service. The numbers reported may be slightly inaccurate as some COs and experiments were not properly recorded.[43]

| Unit Number | Facility | Type of Project | Capacity of CPS ssignees | Dates Approved-Dates Closed |

| 115.28 | University of Illinois | Cold weather | 13 | Nov 30, 1942 to June 22, 1944 |

| 115.31 | Northwestern University Medical School | Diet-altitude | 7 | Aug 20, 1943 to Oct 31, 1944 |

| 115.10 | Massachusetts General Hospital | Sea water | 7 | Sept 15, 1943 to Dec 31, 1945 |

| 115.18 | University of Minnesota | Thiamine | 40 | Sept 15, 1943 to Feb 1, 1946 |

| 115.29 | University of Chicago | High altitude | 1 | Sept 15, 1943 to Jan 20, 1944 |

| 115.30 | University of Illinois | Heat | 8 | Sept 24, 1943 to Feb 31, 1944 |

| 115.16 | University of Michigan | Physiological hygiene | 10 | Oct 11, 1943 to Feb 1, 1946 |

| 115.11 | Massachusetts General Hospital | Malaria | 1 | Feb 24, 1944 to Dec 31, 1945 |

| 115.5 | Welfare Island Hospital | High altitude | 8 | Mar 20, 1944 to Nov 4, 1945 |

| 115.23 | [Manteno State Hospital/] University of Chicago | Malaria | 21 | May 23, 1944 to Aug 12, 1946 |

| 115.13 | Haskins Laboratories | Sensory device | 2 | June 28, 1944 to Dec 1, 1945 |

| 115.27 | Cornell University | Bed rest | 8 | June 30, 1944 to Feb 2,1946 |

| 115.25 | Columbia University | Malaria | 4 | Sept 2, 1944 to June 30, 1946 |

| 115.9 | Stanford University | Malaria | 1 | Sept 25, 1944 to Dec 31, 1945 |

| 115.17 | University of Minnesota | Starvation | 39 | Nov 13, 1944 to Feb 1, 1946 |

| 115.12 | University of Michigan | Weather | 4 | Dec 15, 1944 to Dec 8, 1945 |

| 115.4 | Welfare Island Hospital | Life raft ration | 11 | Feb 5, 1945 to Feb 15, 1945 |

| 115.3 | Welfare Island Hospital | Altitude pressure | 38 | Feb 8, 1945 to Feb 15, 1945 |

| 115.20 | Ohio State University | Physiology | 6 | Apr 21, 1945 to Mar 5, 1946 |

| 115.22 | Goldwater Memorial Hospital | Malaria; [diet] | 36 | July 3, 1945 to May 9, 1946 |

| 115.14 | University of Rochester | Cold weather | 8 | Aug 20, 1945 to Jan 8, 1946 |

| 115.21 | University of Rochester | Physiology | 13 | Aug 25, 1945 to Apr 8, 1946 |

| 115.8 | New York University | Poison gas | 2 | Aug 28, 1945 to Feb 1, 1946 |

| 115.7 | Harvard University | Psycho - acoustic | 13 | Sept 15, 1945 to June 12, 1946 |

| 115.6 | Metropolitan Hospital | Frost bite | 4 | Oct 9 1945 to Dec 27 1945 |

| 115.19 | Massachusetts Institute of Technology | Malaria | 1 | Oct 26, 1945 to Apr 8, 1946 |

| 115.1 | California Institute of Technology | Malaria | 2 | Nov 20, 1945 to Feb 28, 1946 |

| 115.2 | University of Southern California | Altitude pressure | 1 | Jan 4, 1946 to Feb 15, 1946 |

| 115.24 | Massachusetts General Hospital | Malaria; [convalescence] | 28 | Jan 4, 1946 to Aug 9, 1946 |

| 115.15 | Indiana University | Climatology | 4 | Feb 1, 1946 to Sept 26, 1946 |

| 115.26 | New York Hospital | Bed rest | 1 | Feb 18, 1946 to Nov 25, 1946 |

| 115.32 | Mayo Clinic | Aero medical | 2 | Apr 11, 1946 to May 15, 1946 |

Specific Experiments

Typhus: Typhus, a disease transmitted by body lice, was considered to be “one of the most dangerous of the potential epidemic diseases which were expected to occur during or after the war.”[44] The Rockefeller Foundation, with support of the US government, headed an experiment on louse disinfestation techniques. Initially its leadership paid homeless individuals $7 a day to participate, however, the "difficulty in securing suitable subjects” led the foundation to be the first experiment to use American WWII COs as subjects.[45][46] A total of 32 COs volunteered for the experiment.

In July 1942, Dr. Davis and Dr. Wheeler began the experiment with COs at a site in Campton, New Hampshire that became nicknamed “Camp Liceum.” They collected lice from an alcoholic ward of Bellevue Hospital and brought it with them to the facility. For 18 days, the men were required to wear undergarments infested with live lice and their eggs. For the second half, they were split into groups and given various delousing powders.[46]

Most of the powders proved ineffective and the medical legacy of the experiment was short lived; however, it set a precedent for the use of COs in experiments. Only a few years after the study, scientists discovered DDT which helped prevent a Typhus epidemic and eliminated the need for the Lice Experiment's results.[47]

Hepatitis: During the 1940s the cause, method of communication, and treatment of infectious hepatitis were not well understood. Experimentation began with COs working at psychiatric hospitals and expanded to a major research project with 30 to 60 test subjects at the University of Pennsylvania and Yale University. The men were inoculated with infected blood plasma, swallowed nose and throat washings, and the human body wastes of infected patients, and drank contaminated water.[48] The infectious hepatitis research was instrumental in determining that a virus, rather than bacteria, is responsible for the Hepatitis A and that it is transmitted through human filth, serum and drinking water.[48]

Malaria: During the early 1940s, Malaria was a major threat to troops fighting in the Pacific Front and quinine was the chief anti-malarial drug. Made from the bark of the South American cinchona tree, quinine was in short supply during the war, so scientists began searching for alternative treatments. There were over 14 different experiments conducted on COs with an emphasis on malaria research.

In many of the cases, the test subjects were bitten by malarial mosquitoes and when the fever reached its peak after three to four days they were given various experimental treatments.[49][50] During one Malaria experiment at the University of Minnesota, twelve CPS men underwent tests to determine the recovery period for those infected with malaria. This research documented the debilitating effects of the disease and the amount of time required for a complete recovery.[51]

Common cold and atypical pneumonia: CPS men participated in tests in Pinehurst, North Carolina and Gatlinburg, Tennessee during which they drank throat washings contaminated with soldiers' colds and pneumonia. Through this experiment, researchers with the Commission on Acute Respiratory Disease came to the conclusion that colds and some types of pneumonia are caused by a virus rather than bacteria.[50][52]

Minnesota Starvation Experiment: To study the effects of diet and nutrition, Dr. Ancel Keys of the University of Minnesota Laboratory of Physiological Hygiene placed 36 conscientious objectors on a controlled diet. The study was split into three parts: a control period, a semi-starvation period, and a refeeding period.[53] For three months the subjects were given a normal 3,200 calories (13,000 kJ) daily diet depending on the weight. This was followed by six months of a 1,800 calories (7,500 kJ) diet, fewer calories than provided by the famine diet experienced by the civilian population in wartime Europe. The results showed an average of 24% loss in body weight, 40% loss in resting metabolism, decreased heart size, decreased blood pressure, 30% decrease in lung capacity, and other serious effects.[54] The research not only documented the men's ability to maintain physical output, but also the psychological effects of the restrictive calorie diet such as introversion, lethargy, irritability and severe depression. The study then followed the men's long recovery as they returned to a normal diet and regained the weight lost during the experimentation.[55][56]

The study provided valuable insights into hunger and starvation and the results were made available to all major relief agencies concerned with postwar food and nutrition problems, helping to inspire the Marshall Plan.[57] It became the most widely publicized of any of the experiments on COs and the results continue to be beneficial to the study of famine and anorexia.[53]

Non-disease related experiments: A number of other experiments were done to help test soldiers' abilities to survive in the extreme conditions the war presented. These tests included exposure to excessively high altitudes, cold, and heat.[43] For example, to test the effects of extreme heat on soldiers, a group of COs at the University of Rochester rode stationary bikes in 123 degree heat on empty stomachs.[58] In a different experiment, CO participants at Indiana University slept in frigid, temperature-controlled rooms wearing soaked clothing. The results of this study were used to gain information for the army on how different types of clothing responded to cold weather.[59] Experiments also helped to decide adequate survival rations, calculate the duration of time men could survive on life rafts, and calculate the amount of time men could survive drinking only ocean water.

Willingness to participate and public sentiment

Although every COs experience was different, overall, even with the harsh experimental conditions, most participants described their work in the Guinea Pig Units positively. At the time the experiments were thought of as “work of national importance” and an overwhelming number of the COs preferred this form of objection to other CPS manual labor tasks.[39] In fact, "the amount of men not selected for these dreadful experiments after volunteering outpaced the numbers actually chosen".[60] Over 40 years after the experiment, CO Peter D. Watson, discussing his experiences in the Guinea Pig Units at the University of Rochester's medical school, said “it was a chance to serve and to do something worthwhile.’’[61] They took pride in their efforts, as their research directly helped soldiers during WWII and continues to have a lasting effect on the medical field today. Many COs reported that this work served as a form of humanitarian work that aligned with their pacifist and religious beliefs.[62]

Although public views toward COs were generally negative, as they were viewed as cowardly, emasculate, and untrustworthy, after 1944 when the government released their participation in experiments, the media covered the COs involved in experimentation in a positive light. [63][64] The Minnesota Starvation Experiment was featured in Life Magazine in 1945, making it the first of the Guinea Pig Experiments to be widely publicized.[53] After this publication, other newspapers and journals including The Washington Post, Cosmopolitan, World-Telegram, Survey Graphic, and Coronet Magazine began discussing these COs positively.[43] This press coverage tended to focus on the sacrifice the COs were making and the risks they were facing, depicting them as far more patriotic and heroic than prior representations.

Ethical Considerations

Despite the positive medical impact these studies using COs have had, many scholars have deemed the experiments unethical by modern standards. In most of the experiments, the participants were subject to unsafe conditions and many left with permanent negative health effects.

As a young surgeon, C. Everett Koop, who later became the 13th Surgeon General of the United States, was part of the research team at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine. He has since expressed regret for his involvement in the studies. In an interview for the documentary The Good War and Those Who Refused to Fight It, Koop described his experience with CPS test subjects:

And the first time I was introduced to this whole program when I as a young surgeon, was asked to do serial biopsies on their livers to see what the effect of the virus was in the production of the changes in the liver. And in that way, I got to know that a lot of these young men had no idea that the risk they were taking also included death. And some of those youngsters did die and it was a very difficult thing for me to be part of, because you know, you’re powerless, when you’re part of the big team. It couldn't happen today. Internal Review Boards would not permit the use of a live virus in human subjects unless they really understood what was going to happen to them. And I doubt that even if they knew what the risk was, that an Internal Review Board in any academic institution would consent to that kind of experimental work.

War Relief and Seacowboys

In 1945 and 1946, after World War II, ships were converted to livestock ships, also called "cowboy ships". From 1945 to 1947 the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration and the Brethren Service Committee of the Church of the Brethren sent livestock to war-torn countries. These "seagoing cowboys" made about 360 trips on 73 different ships. Of the 7,000 seagoing cowboys, 366 were from the Civilian Public Service, these volunteered to be "seagoing cowboys". The Heifers for Relief project was started by the Church of the Brethren in 1942; in 1953 this became Heifer International.[65] These ships were known as cowboy ships and moved livestock across the Atlantic Ocean. These ships moved horses, heifers, and mules as well as a some chicks, rabbits, and goats.[66][67] [68] [69][70]

Closure and impact

Civilian Public Service men were released from their assignments and the camps closed during March 1947, nineteen months after the end of the war in the Pacific.[71] Reforms in the mental health system continued after the war. The experience of Mennonite COs was instrumental in creating regional mental health facilities in California, Kansas and Maryland.

Lewis Hill, who was in CPS camp number 37 near Coleville, California, together with several other COs founded Pacifica Network and KPFA Radio in Berkeley, California, the world's first listener-sponsored radio station.[72] Poets William Everson and William Stafford were both in CPS camps.[72] Actor Francis (Fritz) William Weaver spent time in the Big Flats (New York) CPS Camp number 46.[73]

Men from the historic peace churches volunteered for relief and reconstruction after their release from CPS. The 1947 Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to American and British Friends Service Committees for their relief work in Europe after the war.[74] Mennonite Central Committee redirected its effort from camp administration to relief and reconstruction in Europe after the war.

Civilian Public Service created a precedent for the Alternative Service Program for conscientious objectors in the United States during the Korean and Vietnam Wars.[75] Although the CPS program was not duplicated, the idea of offering men an opportunity to do "work of national importance" instead of military service was established.

See also

- Civilian Bonds

- Jewish Peace Fellowship

- Swiss Civilian Service

- Zivildienst

People

- Delamere Francis McCloskey, Los Angeles City Council member, 1941–43, opposed the camps

Notes

- Mock,

- Keim p. 18.

- Juhnke p. 103.

- Keim p. 9.

- Keim p. 11.

- Braun.

- Gingerich, pp. 47-50.

- Gingerich pp. 437-8.

- Krahn p. 604.

- Keim, p. 26.

- Gingerich pp. 57 & 338.

- Swarthmore College Peace Collection (Camps) and Keim pp. 107-110.

- Keim p. 30.

- Keim p. 81.

- Includes 12 groups of Mennonites and Amish, plus the Brethren in Christ and Missionary Church. Gingerich p. 340.

- Dyck p. 39.

- Keim, pp. 37-38.

- Keim, pp. 86-94.

- Keim, pp. 95-96.

- Keim, pp. 80-86.

- Keim, pp. 91-93.

- Keim, p. 94.

- Gingerich, p. 388.

- Gingerich, p. 390.

- Krahn p. 609.

- Keim, pp. 57, 98.

- Keim, p. 98.

- Krahn p. 607.

- Keim p. 49.

- Gingerich p. 147.

- Phifer, Gregg (July 2000). "My Brush with History: CPS Smokejumpers". National Smokejumper Association. Archived from the original on October 18, 2011. Retrieved May 27, 2012. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Gingerich p. 213.

- Keim p. 59.

- Good War (Transcripts p. 12)

- Keim pp. 69-70.

- Keim, pp. 58-72.

- Merged with two other organization in 1950 to become National Association of Mental Health (NAMH) and now National Mental Health Association (NMHA)

- Gingerich p. 248.

- "CPS CAMP NUMBER 115". Civilian Public Service. Mennonite Central Committee. 2015.

- Robinson, Robinson, Mitchell Lee (1990). Civilian Public Service during World War II: the dilemmas of conscience and conscription in a free society. Cornell University.

- Keim, pp. 75–80.

- Gingerich, p. 270–273.

- Bateman-House, Alison S. (2014). "Compelled to Volunteer: American Conscientious Objectors to World War II as Subjects of Medical Research". Columbia University.

- “Study of Typhus Fever – Authorization and Designation,” March 18, 1940, folder 259, box 32, series 100, RG1, Rockefeller Foundation Archives, RAC.

- Bauer JH. Sleepy Hollow (NY): RAC; 1942. Jun 29, Testing louse repellents. Folder 261, box 32, series 100, RG 1.

- Bateman-House, Alison (2009). "Men of Peace and the Search for the Perfect Pesticide: Conscientious Objectors, the Rockefeller Foundation, and Typhus Control Research". Public Health Reports. 124 (4): 594–602. doi:10.1177/003335490912400418. ISSN 0033-3549. PMC 2693176. PMID 19618798.

- Bushland, R. C.; Mcalister, L. C.; Jones, Howard A.; Culpepper, G. H. (April 1, 1945). "DDT Powder for the Control of Lice Attacking Man1". Journal of Economic Entomology. 38 (2): 210–217. doi:10.1093/jee/38.2.210. ISSN 1938-291X.

- Keim, pp. 75–76.

- Keim, pp. 76-78.

- Gingerich, p. 272.

- Keim, p. 78.

- Keim, p. 76.

- Russell, Sharman Apt. (2008). Hunger : an Unnatural History. Basic Books. pp. 113–137. ISBN 978-0-7867-2239-6. OCLC 784885620.

- Keys, Ancel Benjamin Drummonds, J. C., BeteiligteR. (1950). The Biology of human starvation. The Univ. of Minnesota Pr. OCLC 252020400.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Keim, p. 79.

- Gingerich, p. 270–271.

- Good War (Alternative Service).

- Schmitt, Eric (May 29, 1989). "They Served Country and Conscience". The New York Times.

- Krehbiel, Nicholas A. (2014). General Lewis B. Hershey and Conscientious Objection During World War II. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 978-0-8262-1941-1. OCLC 1020553623.

- Markam Bryant, “The Thirteen Thousand,” The Antioch Review, no. 1 (1947).

- Schmitt, E. (1989, May 29). They Served Country and Conscience.(National Desk). The New York Times.

- Kleinsasser, P., Ellis, M., Davis, R., Gough, P., & Rohrer, J. (2014). Serving both conscience and nation (ProQuest Dissertations Publishing). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1648419651/

- Leo P. Crespi, “Public Opinion Toward Conscientious Objectors: II. Measure of National ApprovalDisapproval.” Journal of Psychology 19: 1945, 212.

- Crespi, L. (1945). Public Opinion Toward Conscientious Objectors: II. Measurement of National Approval-Disapproval. The Journal of Psychology, 19(2), 209–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.1945.9917230

- Heifer International

- Swarthmore library, Seagoing Cowboys, Civilian Public Service, by Anne M. Yoder, Archivist, SCPC

- Sea going cowboys

- Seacowboys report

- Who were the Seagoing Cowboys, by Jackie Turnquist

- Seagoing Cowboys, S. S. Pierre Victory, by Peggy Reiff Miller

- Gingerich, p. 385.

- Good War (Arts)

- Swarthmore College Peace Collection (Personal Papers).

- Good War (Post-war Contributions)

- Keim, p. 100.

References

- Braun, Abraham, Th. Block and Lawrence Klippenstein (1989). "Forsteidienst, Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online". Retrieved July 7, 2008.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Dyck, John M. (1997). Faith Under Test: Alternative Service During World War II in the U.S. and Canada, Gospel Publishers.

- Gingerich, Melvin (1949), Service for Peace, A History of Mennonite Civilian Public Service, Mennonite Central Committee.

- Juhnke, James C. (1975), A People of Two Kingdoms: the Political Acculturation of the Kansas Mennonites, Faith and Life Press. ISBN 0-87303-662-X

- Keim, Albert N. (1990). The CPS Story, Good Books. ISBN 1-56148-002-9

- Kovac, Jeffrey, Refusing War, Affirming Peace: A History of Civilian Public Service Camp #21 at Cascade Locks, Oregon State University Press, 2009

- Krahn, Cornelius, Gingerich, Melvin & Harms, Orlando (Eds.) (1955). The Mennonite Encyclopedia, Volume I, pp. 604–611. Mennonite Publishing House.

- Mock, Melanie Springer (2003). Writing Peace: The Unheard Voices of Great War Mennonite Objectors, Cascadia Publishing House. ISBN 1-931038-09-0

- Swarthmore College Peace Collection:

- "Civilian Public Service Personal Papers and Collected Materials, 1939-present". [Swarthmore College Peace Collection]. Retrieved July 7, 2008.

- "List of CPS Camps (by Camp Number)". [Swarthmore College Peace Collection]. Retrieved July 7, 2008.

- "The Good War and Those Who Refused to Fight It". PBS. Retrieved July 7, 2008.

- "Alternative Service". PBS. Retrieved July 7, 2008.

- "The Arts". PBS. Retrieved July 16, 2008.

- "Post-war Contributions". PBS. Retrieved July 16, 2008.

- "Transcript" (PDF). PBS. Retrieved July 7, 2008.

Further reading

- Alexander, Paul (2008) Peace to War: Shifting Allegiances in the Assemblies of God, Telford, PA: Cascadia Publishing, ISBN 978-1-931038-58-4

- Cottrell, Robert C. (2006) Smokejumpers of the Civilian Public Service in World War II: Conscientious Objectors As Firefighters, Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, ISBN 0-7864-2533-4

- Kniss, Lloy A. (2002) I Couldn't Fight and Other CO Stories 1917—1960, Ephrata, PA.: Eastern Mennonite Publications

- National Service Board for Religious Objectors (1947) Directory of Civilian Public Service: May, 1941 to March, 1947, Washington, D.C., 167 pages, ASIN: B000KI7H1C.

- Schlabach, Mose A. (2003) Memories of CPS Camp Days, Volumes I and II, Sugarcreek, OH: Carlisle Printing

- Van Dyck, Harry R. (1990) Exercise of Conscience: A World War II Objector Remembers, Buffalo, NY: Prometheus Books. ISBN 0-87975-584-9

- Wittlinger, Carlton (1978) Quest for Piety and Obedience: The Story of the Brethren in Christ, Nappanee, IN: Evangel Press, ISBN 0-916035-05-0

- Zahn Gordon C., Another Part of the War: The Camp Simon Story (University of Massacvhusetts Press, 1979), ISBN 978-0-870232-59-6

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Civilian Public Service. |

- Civilian Public Service in Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online (GAMEO)

- They starved so that others be better fed: remembering Ancel Keys and the Minnesota experiment

- Lewis & Clark College: CPS Camp Newsletters Digital Collection

- Oral history interview with Charles K. Griffith, a conscientious objector during WW II from the Veterans History Project at Central Connecticut State University

- Civilian Public Service, Searchable database of all 12,000 draftees who served in CPS, plus descriptions of the work in more than 150 camps. Includes images, stories and some primary source documents.

- Civilian Public Service Smokejumpers Oral History Project (University of Montana Archives)