Cité Soleil

Cité Soleil (Haitian Creole: Site Solèy; English: Sun City) is an extremely impoverished and densely populated commune located in the Port-au-Prince metropolitan area in Haiti. Cité Soleil originally developed as a shanty town and grew to an estimated 200,000 to 400,000 residents, the majority of whom live in extreme poverty.[2] The area is generally regarded as one of the poorest and most dangerous areas of the Western Hemisphere and it is one of the biggest slums in the Northern Hemisphere. The area has virtually no sewers and has a poorly maintained open canal system that serves as its sewage system, few formal businesses but many local commercial activities and enterprises, sporadic but largely unpaid for, electricity, a few hospitals, and two government schools, Lycee Nationale de Cite Soleil, and Ecole Nationale de Cite Soleil. For several years until 2007, the area was ruled by a number of gangs, each controlling their own sectors. But government control was reestablished after a series of operations in early 2007 by the United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH)[3] with the participation of the local population.

Cité Soleil Site Solèy | |

|---|---|

Cité Soleil | |

Cité Soleil | |

| Coordinates: 18°34′40″N 72°19′55″W | |

| Country | |

| Department | Ouest |

| Arrondissement | Port-au-Prince |

| Area | |

| • Total | 21.81 km2 (8.42 sq mi) |

| Population (2015 Est.)[1] | |

| • Total | 265,072 |

| • Density | 12,154/km2 (31,480/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (EST) |

The neighborhood is located at the western end of the runway of Toussaint Louverture International Airport and adjoins the grounds of the former Hasco Haitian American sugar complex. It began with the construction in 1958 of homes for 52 families. In the summer of 1966, a mysterious fire in the slum of La Saline displaced many of its residents. 1,197 homes were built there and it was named Cité Simone, after Haiti's First Lady Simone Ovide Duvalier. In 1972, a major fire near the central market of Port-au-Prince displaced yet more people who ended up in the Boston section of Cité Simone. In 1983, the census recorded 82,191 people in Cité Simone.[4]

Originally designed to house sugar workers, Cité Simone later housed manual laborers for a local Export Processing Zone (EPZ). Neoliberal reforms beginning in the early 1970s made this place a magnet for squatters from around the countryside looking for work in the newly constructed factories. This movement accelerated in the early 1980s with the destruction of the Creole pigs by American order in response to an African swine flu outbreak, followed by the rise of Finance Minister Leslie Delatour who took this post following the ouster of Jean-Claude Duvalier in 1986. Delatour openly advocated the depopulation of much of the Haitian countryside and that these people work instead in cities, living in places such as the newly named Cité Soleil, though not for Hasco that Delatour shut down in 1987. This industrial sector was however damaged following the 1991 coup d'état that deposed President Jean-Bertrand Aristide, causing a boycott of Haitian products that closed the EPZ.[5] Cité Soleil continued to be plagued by extreme poverty and persistent unemployment, with high rates of illiteracy.[3]

Half of the houses of Cité Soleil are made of cement with a metal roof, half are made completely of scavenged material. An estimated 60 to 70% of houses have no access to a latrine, particularly in the marshy Brooklyn area which includes Cité Carton.[6]

Armed gangs roamed the streets and terrorized the neighborhood. Every few blocks was controlled by one of more than 30 armed factions.[7] Though the gangs no longer rule, murder, rape, kidnapping, looting, and shootings are still common. The area has been called a "microcosm of all the ills in Haitian society: endemic unemployment, illiteracy, non-existent public services, unsanitary conditions, widespread crime and armed violence".[8]

After the devastating 2010 earthquake, it took nearly two weeks for relief aid to arrive in Cité-Soleil.[9]

Overview

Most of the residents of Cité-Soleil are children or young adults. The mortality rate is high from diseases such as AIDS, or from violence.[3] At times Cité Soleil has been filled with armed gangs. Politically affiliated gangs or militias, often with quasi-official powers, have been a regular element of Haitian politics throughout the country's history.

The fighting led to wide scale charges by neighborhood residents that the United Nations stabilizing force has permitted conditions that led to the death of unarmed bystanders.[10] In 2004 they were accused of ignoring violence by the Haitian police, the criminal roots of the kidnapping and undermining of president Jean Bertrand Aristide's security police force.[11]

During the mid-1990s, the city's population was terrorized by armed gangs which drove the local police out; this situation prevented officials aid workers from intervening to provide help.[12] In 1999, Cité Soleil was set on fire by a gang and at least 50 shacks were burned.[13] By 2002, the violence escalated as the gangs began warring with each other in addition to preying on ordinary people. Many inhabitants had temporarily left to escape the turmoil.[14] In a series of operations from 2004 to 2007, UN peacekeepers tried to seize control from the gangs in Cité Soleil and end the chaos.[15] Although the United Nations Stabilization Mission (MINUSTAH) has been deployed since 2004, it continues to struggle for control over the armed gangs and the violent confrontations continue. MINUSTAH maintains an armed checkpoint at the entrance to Cité Soleil and the road is blocked with armed vehicles.[3] In December 2004, a group of armed ex-soldiers occupied Aristide's home against the wishes of the Haitian government.[16] In January 2006, two Jordanian peacekeepers were killed in Cité Soleil.[17] The UN has described the human rights situation in Haiti as "catastrophic".[18]

Current status

The United Nations Stabilization Mission (MINUSTAH) has been in Haiti since 2004. It now numbers 8,000 troops but continues to struggle for control over the armed gangs. In October 2006, a group of heavily armed Haitian police were able to enter Cité Soleil for the first time in three years and were able to remain one hour as armored UN troops patrolled the area. Since this is where the armed gangs take their kidnap victims, the Haitian police's ability to penetrate the area even for such a short time was seen as a sign of progress.[19] Before Christmas 2006, the UN force announced that it would take a tougher stance against gang members in Port-au-Prince, but since then the atmosphere there has not improved; the armed roadblocks and barbed wire barricades have not been removed. After four people were killed and another six injured in a UN operation exchange of fire with criminals in Cité Soleil in late January 2007, the United States announced that it would contribute $20 million to create jobs in Cité Soleil.[20][21]

In early February 2007, 700 UN troops flooded Cité Soleil, resulting in a major gun battle. Although the troops make regular forcible entries into the area, a spokesperson said this one was the largest attempted so far by the UN troops.[22] On July 28, 2007, Edmond Mulet, the UN Special Representative in Haiti, warned of a sharp increase in lynchings and other mob attacks in Haiti. He said that the UN Stabilization Mission would launch a campaign to remind people that lynching is a crime.[23]

On August 2, 2007, the UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon arrived in Haiti to assess the role of the UN forces, announcing that he would visit Cité Soleil during his visit. He said that as it is Haiti's largest slum, it is the most important target for UN peacekeepers in gaining control over the armed gangs. The Haitian president René Préval has expressed ambivalent feelings about the UN security presence, saying, "If the Haitian people were asked if they wanted the UN forces to leave they would say yes."[24] Survivors at times blame the UN peacekeepers for deaths of relatives.[25]

Critics of UN Stabilization Mission's plan feel that the United Nations mandate is unrealistic, treating a political problem as a security problem.[26]

2010 Haiti earthquake

On January 12, 2010, at 21:53 UTC (4:53 PM local time) Haiti was struck by a magnitude-7.0 earthquake, the country's most severe earthquake in over 200 years.[27] The epicenter of the quake was just outside the Haitian capital, Port-au-Prince, in Léogâne.[28] As the biggest slum of Port-au-Prince, Cité Soleil fared relatively well, as most of its cinder block and corrugated steel shacks survived. Médecins Sans Frontières reopened its Choscal Hospital (which operated between 2005 and 2007 during the gang war) in the heart of the slum within 24 hours.[29] However, the area remained in desperate need of help, according to World Emergency Relief.[30]

Gang members who escaped from Haiti's damaged prison returned to the area to continue to commit crimes.[31] The crime rate rose and police urged citizens to take matters into their own hands.[32] As of January 23, 2010, Cité Soleil had largely remained neglected by earthquake relief workers and was doing what it could to survive and help on its own.[33] Samaritan's Purse worked in Cité Soleil by building the largest cholera treatment center during the outbreak.[34]

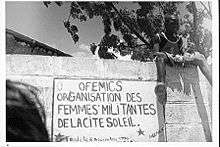

Gallery

Cité Soleil, 2002

Cité Soleil, 2002 Cité Soleil, 2002

Cité Soleil, 2002 Cité Soleil, 2002

Cité Soleil, 2002

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cité Soleil. |

- Bureau des Avocats Internationaux

- Cité Soleil raid of 2007

- Konbit Soley Leve

- Emmanuel Wilmer

Footnotes

- "Mars 2015 Population Totale, Population de 18 ans et Plus Menages et Densites Estimes en 2015" (PDF). Institut Haïtien de Statistique et d’Informatique (IHSI). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 November 2015. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- "Cité-Soleil: Grinding poverty, relentless violence". International Committee of the Red Cross. Archived from the original on 2007-09-30. Retrieved 2007-08-16.

- "INTELLIGENCE-LED PEACEKEEPING: The United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH), 2006-07". Intelligence and National Security. Retrieved 2010-09-10.

- "Project Paper: Urban Health and Community Development – Phase II" (PDF). USAID/Haiti. 25 May 1984. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- "Quake aid finally reaches Cité Soleil". euronews. 2010-01-25. Retrieved 25 January 2010.

- "Activity Report No. 21: A Plan for CDS to Establish a Water and Sanitation District in Cité Soleil, Haiti and Monitoring Visit Report" (PDF). USAID Mission to Haiti. May 1996. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- "Glimmers of Hope in Cité Soleil". WashingtonPost.com. 2 February 2006. Archived from the original on 18 April 2006. Retrieved 2006-12-30.

- Revol, Didier (2006). "Hoping for change in Haiti's Cité-Soleil". International Red Cross. Retrieved 24 January 2010.

- "Quake aid finally reaches Haiti's Cité-Soleil slum". euronews. January 25, 2010. Retrieved 25 January 2010.

- "The Cité Soleil Massacre Declassification Project". Archived from the original on 2010-02-27. Retrieved 2010-01-21.

- "Document - Haiti: Amnesty International calls on the transitional government to set up an independent commission of inquiry into summary executions attributed to members of the Haitian National Police". Amnesty International. 2004. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- "MINUSTAH Focuses on Security in Haiti's Cité Soleil Slum". Americas Quarterly. Americas Society and Council of the Americas. August 2009. Retrieved 2010-01-20.

- "Haitian shantytown torched in revenge attack". BBC News. 1999-12-23. Retrieved 2007-08-16.

- "Violence Between Gangs in Cité Soleil". 9 September 2002. Retrieved 2006-12-30.

- "UN peacekeepers storm Haiti slum". BBC News. 2004-12-15. Retrieved 2007-08-16.

- "Ex-soldiers occupy Aristide home". BBC News. 2004-12-16. Retrieved 2007-08-16.

- "Two UN soldiers killed in Haiti". BBC News. 2006-01-18. Retrieved 2007-08-16.

- "Country profile: Haiti". BBC News. 2009-11-16. Retrieved 2007-08-16.

- "Haiti police visit gang stronghold". BBC Caribbean. Retrieved 2007-08-02.

- "HAITI: Poor Residents of Capital Describe a State of Siege". ipsnews. Archived from the original on 2007-08-14. Retrieved 2007-08-02.

- "US aid for Cité Soleil". BBC Caribbean. Retrieved 2007-08-02.

- "UN troops flood into Haiti slum". BBC New. Retrieved 2007-08-14.

- "UN concerned at Haiti lynchings". BBC Caribbean. 2007-07-28. Retrieved 2007-08-02.

- "UN chief visits Haiti". BBC Caribbean. Retrieved 2007-08-02.

- Jordan, Sandra (2007-04-01). "Haiti's children die in UN crossfire". London: Guardian Unlimited. Retrieved 2007-08-02.

- Guidi, Ruxandra (August 20, 2009). "MINUSTAH Focuses on Security in Haiti's Cité Soleil Slum". Americas Quarterly. The Americas Society and Council for the Americas. Retrieved 2010-01-20.

- "Magnitude 7.0 – Haiti Region". Archived from the original on January 15, 2010. Retrieved January 12, 2010.

- "Major earthquake off Haiti causes hospital to collapse – Telegraph". London: telegraph.co.uk. 2010-01-12. Retrieved 2010-01-20.

- Marlowe, Chris (January 20, 2010). "Just this once, the stricken capital's biggest slum was comparatively lucky". The Thomas Reuters Foundation. Retrieved 2010-01-20.

- Hobbes, Lara (January 18, 2010). "Haiti: Much needed supplies for Cité Soleil". The Irish Times. Retrieved 2010-01-20.

- Brown, Tom (January 17, 2010). "Gangs return to Haiti slum after quake prison break". Reuters. Retrieved 22 January 2010.

- Katz, Jonathan (January 19, 2010). "Gang members in Haitian slum profit from disaster". streetgangs.com. Retrieved 2010-01-20.

- Davis, Nick (2010-01-23). "Haiti's Cité Soleil still deprived of post-quake help". BBC News, Haiti. Retrieved 23 January 2010.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-04-08. Retrieved 2014-04-07.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

References

- Nicolas Rossier. "Aristide and the Endless Revolution". www.aristidethefilm.com

- Michael Deibert. Notes from the Last Testament: The Struggle for Haiti. Seven Stories Press, New York, 2005. ISBN 1-58322-697-4.

- Aristide's Tinderbox: Haitian Militants Losing Faith in President’s Promise of Reform (August 2002) by Michael Deibert

- HAITI: Poor Residents of Capital Describe a State of Siege"(February 2007)

- HaitiAction.net (April 25, 2005): "Cité Soleil under siege: Haiti's elite, U.N., and fat cat NGOs paralyzed"

- Haiti Report (September 9, 2002): "Violence Between Gangs in Cite Soleil"

- DemocracyNow.org (December 29, 2006): "Another Massacre in Cite Soleil?"

- RedCross.int (no date): "Hoping for change in Haiti's Cité-Soleil", by Didier Revol

- ZMag.org (July 17, 2005): "Murdering Haiti", by Yves Engler

- Counterpunch.org (November 24, 2006): "The UN Fails Haiti, Again", by Kim Ives

- New Left Review #27 (May-June 2004): "Operation Zero in Haiti", by Peter Hallward

- Centre for Civil Society: Summary of Depelchin, Jacques (2004), "Haiti 1804 as an Event - Fidelity to Freedom, Why has it been so difficult to achieve?", CCS Seminar Series: 1-17

- Cité Soleil Water Truck