Circassians in Israel

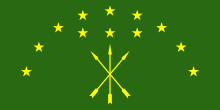

Circassians in Israel (Adyghe: Адыгэхэу Исраэл исыхэр; Hebrew: הצ'רקסים בישראל) refers to the Circassian people who live in Israel. They hail from a Northwest Caucasian[4] ethnic group native to Circassia who mostly adhere to Islam.

Адыгэхэу Исраэл исыхэр הצ'רקסים בישראל | |

|---|---|

| Total population | |

| c. 4,000[1][2]–5,000[3] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Kfar Kama, Rehaniya | |

| Languages | |

| Circassian, Hebrew, Arabic, English | |

| Religion | |

| Sunni Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Circassians |

Circassians in Israel are Sunni Muslims; they number about 4,000 and live primarily in two towns: Kfar Kama (Adyghe: Кфар Кама), and Rehaniya (Adyghe: Рихьаные). They are descended from two groups settled in the Galilee by the Ottoman Empire in the 1870s.

Circassian men serve in the Israeli military.[5] Along with the Druze, they are the other minority group in the country for whom male military service in the IDF is mandatory.[6]

History

Ottoman era

Circassia was a Christian land for 1,000 years, but from the 16th century to the 19th century, they were Islamized under the influence of Crimean Tatars and Ottoman Turks.[5] The Circassians arrived in the Middle East after they were expelled from their homeland in the northwestern Caucasus. The Circassians, who fought during the Russo-Circassian War in the mid-to-late 19th century against the Russian Empire captured the northern Caucasus, were massacred and expelled by Czarist Russia from the Caucasus.[7] The Ottoman Empire, which saw the Circassians as experienced fighters, absorbed them in their territory and settled them in sparsely populated areas, including the Galilee.[8]

The Circassian exiles established Rehaniya (nine miles north of Safed) in 1878, and Kfar Kama (13 miles southwest of Tiberias) in 1876.[9][5] After having been deported a second time, this time from the Balkans, by Russia, Ottoman authorities settled Circassians in areas of the Levant as a bulwark against the Bedouins and Druze, who had at times resisted Ottoman rule as well as any hint of Arab nationalism, while avoiding settling Circassians among the Maronites due to the international problems it could cause.[10][11]

At first, the Circassian settlers faced many challenges. The Bedouin viewed them as "squatters" of their pastures and appropriators of their springs, as well as pro-Ottoman agents placed there to undermine their autonomy, and Arab nationalism as it emerged tended to regard Circassians with suspicion; Circassian culture occasionally clashed with Arab mores as well, with local Arabs looking with horror upon the public dancing of Circassian men and women mixed together in festivals.[11] At the time, Ottoman rule of the area was light and there was no real government and no law enforcement, and in various areas of the wider Levant region armed conflict not infrequently broke out between Circassians and other local groups, especially Bedouin and Druze groups in Syria, occasionally with little or no Ottoman intervention; some of these feuds continued as late as the mid-20th century[12] The Chechen community of Syria, which had arrived at the same time as the Circassians, were nearly wiped out by disease, war, and destruction by 1880.[13] However in Northern Israel the Circassians prevailed and European travelers praised their "advanced agricultural methods" and skill in animal husbandry.[13]

Throughout the time of the Ottoman Empire, Circassians kept to themselves and maintained their separate identity, even having their own courts, in which they would tolerate no outside influence, and various travelers noted that they never forgot their homeland, for which they continually yearned.[14]

British Mandate

Circassians in Palestine maintained good relations with the Yishuv and later the Jewish community in Israel, in part due to the language shared with many of the First Aliyah immigrants from Russia who settled in the Galilee.[15] The Circassian community in Palestine helped with the migration of Jews into the British Mandate of Palestine, which was illegal under British rule, in part due to relative cultural similarities such as having a sedentary culture.[15] Circassians and Jews also sympathized with each other's histories of exile.[15] When conflict between Jews and Arabs began during the British Mandate, the Circassians most often took either neutral or pro-Jewish stances.[5]

State of Israel

Circassians fought on the Israeli side of the War of Independence. At their community leaders' request, since 1958, all male Circassians must complete the mandatory military service in the Israel Defense Forces upon reaching the age of majority, while females do not.[16] In this, they are equal to the Israeli Jews and the Israeli Druze populations living in the State of Israel proper (this excludes most of the Druze population living on the Golan Heights). The percentage of the army recruits among the Circassian community in Israel is particularly high. Many Circassians also serve in the Israel National Police, Israel Border Police, and the Israel Prison Service.

In 1976, the Circassian community won the right to maintain its own educational system separate from the Israeli government's Department of Arab Affairs. As a result, the community manages its own separate educational system, which ensures that its culture is passed down to the younger generations.[17] In 2011, a bill was passed by the Knesset to allocate NIS 680 million to the development of education, tourism, and infrastructure in Circassian and Druze villages.[18][15]

Demography

Israeli Circassians have adopted the practice of smaller families,[19] with an average of two children per family,[19] compared to the national rate of 3.73 children per family.[19]

They speak both Adyghe and Hebrew, and many also speak Arabic and English, while cultivating their unique heritage and culture.[20]

Circassian identity

Although Circassians are loyal to Israel, serve in the IDF, and have "prospered" as part of Israel, while preserving their language and culture,[15][21] for many Israeli Circassians, their primary loyalty remains toward their scattered nation with, for some, a desire to "gather all the Circassians in the same place, whether it's autonomy, a republic within Russia, or a proper state".[15] Influenced by the global movement of Circassian nationalism, some Israeli Circassians have returned to Russian-ruled Circassia despite the current political situation in the North Caucasus, much to the dismay of their Israeli Jewish neighbors who would rather they stay.[22] Some Circassians who emigrated to Circassia have returned after becoming disillusioned with the low standard of living in the Circassian homeland, though some have stayed.[22]

Socioeconomic position

In 2012, it was reported that 80% of the younger generation of Circassians in Israel had a post-secondary degree.[15] Overall, in Israel, the percentage of adult citizens with a post-secondary degree is 49%.[23]

In 2007, Circassian and Druze authorities in Israel launched a joint market initiative to invest in the growing tourism industry for bed-and-breakfast stays in Circassian and Druze villages, giving outsiders a chance to experience their cultures.[15]

Circassians are regarded as being both "politically and ideologically" closer to Israeli society, although lately, "at the margins", there has been a renewed emphasis on their Islamic identity, which is thought to be due to Islamophobia coming from some sectors of Israeli society.[15] According to Eleonore Merza: "while the Israeli Circassians are treated quite differently from the Palestinians, they are still ... often victims of discrimination".[24] Shlomo Hasson writes that on the one hand, there are elements of equality, while on the other hand, there is exclusion, inequality, and prolonged discrimination".[25] On the one hand, Circassians in Israel exercise their civil rights. "They are entitled to vote and be elected to the representative bodies of the state." However, on the other hand, he says, "there is inequality between Jews and the minorities. This inequality is expressed in discrimination in the allocation of resources for education, for local government, in unemployment and getting jobs, and especially in the civil service".[26] In 2009, Circassian and Druze activists called on the government to cancel controversial land appropriations and to increase funding to Circassian community.[27] According to these activists, "Circassians receive less than Arab or Haredi-religious communities, despite "sixty years of loyalty".[27] In response to the protests, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu asked the Circassian and Druze communities for "patience", citing the global financial crisis that was occurring in 2009.[27] In 2011, in response to the concerns that had been raised by the activists from the Circassian and Druze communities,[15] the Israeli Knesset approved an allocation of NIS 680 million to aid the development of education, employment, housing, and tourism, as well as assistance for the needs of discharged Druze and Circassian soldiers,[15][18] the bill having passed with the support of Likud, Shas, and Yisrael Beiteinu.[18]

Geographic dispersion

The Circassian community of Israel is concentrated almost entirely in the villages of Kfar Kama (population c. 3,000) and Rehaniya (population c. 1,000). In contrast to Circassian communities in other Middle Eastern countries, which have lost much of their traditions, Israeli Circassians have carefully preserved their culture. More than 90% of Circassians return to their villages after completing their military service and studies. Despite the difficulty of finding marriage partners within a community of 4,000, Israeli Circassians mostly shun intermarriage. Although some Arabs moved to Kfar Kama, they quickly integrated into local society, and left no lasting cultural impression. Intermarriage is widely regarded as a taboo there. Rehaniya absorbed larger numbers of internally displaced Arab refugees during the 1948 war, and as a result, intermarriage with non-Circassians, while still avoided for the most part, became more acceptable there.[28][19]

Most of the Circassians in Kfar Kama are Shapsughs, while those in Rehaniya are mostly Abzakhs.[29]

Circassian families in Israel

- Abrag (Adyghe: Абрэгь)

- Ashmuz or Achmuzh or Achmiz (Adyghe: Ачъумыжъ)

- Bat (Adyghe: Бат)

- Batwash (Adyghe: БэтIыуашъ)

- Bghana (Adyghe: Бгъанэ)

- Blanghaps (Adyghe: БлэнгъэпсI)

- Choshha or Shoshha (Adyghe: Чъушъхьэ)

- Gorkozh (Adyghe: ГъоркIожъ)

- Hadish (Adyghe: Хьэдищ)

- Hako or Hakho (Adyghe: Хьэхъу)

- Hazal (Adyghe: Хъэзэл)

- Kobla (Adyghe: Коблэ)

- Lauz (Adyghe: ЛъыIужъ)

- Libai or Labai (Adyghe: ЛIыпый)

- Nago (Adyghe: Наго)

- Napso (Adyghe: Нэпсэу)

- Nash (Adyghe: Наш)

- Natkho or Natcho (Adyghe: Натхъо)

- Qal (Adyghe: Къалыкъу)

- Qatizh (Adyghe: Къэтыжъ)

- Sagas or Shagash (Adyghe: Шъэгьашъ)

- Shamsi (Adyghe: Чъуэмшъо)

- Showgan (Adyghe: Шэугьэн)

- Shaga (Adyghe: Шъуагьэ)

- Thawcho (Adyghe: Тхьэухъо)

- Zazi (Adyghe: Зази)

Notable people

- Bibras Natkho – Israeli-Circassian footballer, who plays as a midfielder for Serbian Partizan and also serves as the captain of the Israel national team

- Izhak Nash – Israeli-Circassian footballer who plays in the Israeli Premier League

- Nili Natkho – late Israeli-Circassian basketball player who played for Maccabi Raanana and Elitzur Ramla

See also

References

- Besleney, Zeynel Abidin (2014). The Circassian Diaspora in Turkey: A Political History. Routledge. p. 96. ISBN 978-1-317-91004-6.

- Torstrick, Rebecca L. (2004). Culture and Customs of Israel. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-313-32091-0.

- Louër, Laurence (2007). To be an Arab in Israel. New York City, NY: Columbia University Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-231-14068-3.

- One Europe, Many Nations: A Historical Dictionary of European National Groups. Questia Online Library. 25 August 2010. p. 12.

- "PEOPLE: Minority Communities". Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 2013. Retrieved May 6, 2020.

- Richmond, Walter (2013). The Circassian Genocide. Rutgers University Press. back cover. ISBN 978-0-8135-6069-4.

- The Circassians in Israel Archived 2013-04-16 at the Wayback Machine

- Circassians (in Rehaniya and Kfar Kama)

- Kadir Natho (2009). Circassian history. p. 517.

- Walter Richmond. The Circassian Genocide. pp. 113–114.

- Walter Richmond. Circassian genocide. pp. 113–114, 117–118.

- Walter Richmond. Circassian genocide. p. 114.

- Walter Richmond. Circassian genocide. p. =118.

- Oren Kessler (20 August 2012). "Circassians Are Israel's Other Muslims". Forward. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

- "www.circassianworld.com". Archived from the original on 2013-04-17. Retrieved 2010-02-09.

- Circassians, Descendants of Russian Muslims, Fight for Identity in Israel

- Hagar Einav (13 February 2011). "Cabinet approves NIS 680M for Druze, Circassian towns". Retrieved 3 March 2018.

- Sedan, Gil; Westheimer, Ruth K. (2015). The Unknown Face of Islam: The Circassians in Israel. Brooklyn, NY: Lantern Books. ISBN 978-1-59056-502-5.

- Circassians in Israel

- Kadir Natho. Circassian history. pp. 517–518.

- Walter Richmond. Circassian genocide. p. 159.

- "Key Facts For Israel". Keepeek. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- Eleonore Merza, « The Israeli Circassians: non-Arab Arabs », Bulletin du Centre de recherche français à Jérusalem [En ligne], 23 | 2012, mis en ligne le 20 février 2013, Consulté le 12 juin 2017. URL : http://bcrfj.revues.org/7250. All non-Jewish people are discriminated, says Eleonore Merza, and Circassians too, even if they have Israeli citizenship, p. 28, https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00769910/document.

- Shlomo Hasson, Relations between Jews and Arabs in Israel Future Scenarios, 2012, University of Maryland, Institute for Israel Studies, https://cpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/blog.umd.edu/dist/b/504/files/2017/08/2023oneenglish-288g8dg.pdf

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-12-22. Retrieved 2017-06-13.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Maayana Miskin (7 February 2009). "Druze, Circassians Protest in North". Arutz Sheva. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- Gilad, Moshe (5 July 2012). "A Slightly Rarefied Circassian Day Trip". Haaretz. Tel Aviv, Israel. Archived from the original on 4 April 2016. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

I assume it must be a complex and heavy costume, not exactly the latest wrinkle for the blistering Israeli summer. But a moment later, tracing a slender hourglass shape in the air, he explains that even his slim frame would not fit into a Circassian belt without some heavy dieting. "Our traditional costume is made for a man with a hip measurement of 50 centimeters [about 20 inches]", he said. "I couldn't wear it today. Circassian men is supposed to look different."

- Moshe Gilad (5 July 2012). "A Slightly Rarefied Circassian Day Trip". Haaretz. Retrieved 3 March 2018.