Church of Saint Demetrius, Budapest

The Church of Saint Demetrius (Hungarian: Szent Demeter-templom, Serbian Latin: Crkva Svetog Dimitrija) was a Serbian Orthodox church in Budapest, Hungary, located in the Tabán area. It was built between 1742 and 1751 in Central European Baroque style by the Serbian community of Buda, and served as the co-cathedral of the Eparchy of Buda. The building was seriously damaged in the siege of Budapest in 1945, and the ruins were demolished in 1949.

History

Establishment and early history

The first group of Serbian refugees arrived at Buda in the first half of November 1690. They belonged to the great migration of the Serbs from the Ottoman Empire to the Kingdom of Hungary led by Arsenije III Crnojević, the Archbishop of Peć and Serbian Patriarch. The Cameral Administration of Buda settled almost 600 families in the part of the lower town between Castle Hill and Gellért Hill which had been destroyed during the siege of Buda in 1686. The new neighbourhood was called Tabán, Ratzenstadt or Rácváros, the "town of the Serbs". The first census in 1696 found more than 1000 Serbian families in the Tabán or about 5000 people. The majority of the new settlers in Tabán followed the Orthodox faith: from among the taxpayer heads of the families, 461 belonged to the Serbian Orthodox Church and 250 were Catholics in 1702.[1]

During the 18th century the Serbian community increased in number and wealth, and established its own institutions. The former Ottoman mosque of Pasha Sokollu Mustafa was converted into a Catholic church while the Orthodox Serbs built their own church nearby. The first temporary church was made of wood but construction of a new stone building shortly began after the Cameral Administration issued a permit on 23 September 1697. This was consecrated in 1698 by Arsenije III Crnojević although the tower was only added in 1716.[2] The Tabán parish had a stavropegial status being directly under the jurisdiction the Patriarch.

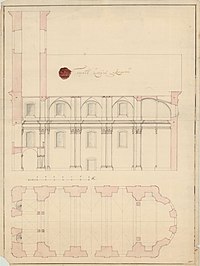

Due to the frequent floods of the Danube, the church soon went to ruin, and in 1738 the townspeople – in consultation with the Bishop of Buda, Vasilije Dimitrijević – made a decision to replace it with a more durable and monumental structure. The design of the new church was entrusted to architect Ádám Mayerhoffer, and the contract was signed on 29 March 1741. The building permit was only issued on 28 April 1742, construction work began on 1 May 1742, and the vault and the roof of the nave was already complete on 26 November. The original plans were slightly modified in the final build. Due to a shortage of money the new church was equipped with icons salvaged from the previous building between 1745 and 1747. In 1751 Bishop Dionisije Novaković consecrated the church to the Holy Trinity but a chapel on the loft was established in the honor of Saint Demetrius to carry on the tradition. The Tabán church was the largest church building in the whole Metropolitanate of Karlovci.[3]

19th century

At first the tower had a simple pyramidal roof clad with shingles but in 1775 a new copper spire was made. The richly decorated spire, designed by Mihajlo Sokolović, was one of the most beautiful Rococo church spires in Central Europe. A painted and gilt wood model was made by Joseph Leonard Weber in 1774 which still exists.[4]

The church completely burned out in the Great Tabán Fire of 1810 which destroyed the whole district, "only its copper spire survived" as a contemporary report claimed.[5] The reconstruction was a long process lasting through the whole decade. The surroundings of the church also changed during the renewal of the area because a new square was created along the southern and eastern side of the church which was called Kirchenplatz (Egyház tér) and served as the main square of the district. In this new setting the church had a narrow churchyard on the south and the east, and it was surrounded by a courtyard and smaller buildings owned by the Serbian parish on the northern and western sides.[6]

The first half of the 19th century was the heyday of Serbian culture in Buda where local intellectuals established strong connections with the national awakening movement of the Hungarian Reform Era, and even took part in the literary and cultural debates of their Hungarian compatriots. They also paid attention to the national and cultural renaissance unfolding in Serbia, and were part of the Serbian enlightenment. Petar Vitković (Péter Vitkovics) was the priest of the Tabán church from 1803 until his death in 1808. He came from an old Serbian family in Eger but he left his hometown for Buda later in his life. An erudite and jovial man, and a polyglot speaking Serbian, Hungarian, German, Latin and Greek, he wrote several treatises and orations. His large personal library was destroyed in the fire of 1810.[7] His elder son, Mihailo Vitković (Mihály Vitkovics) was a Serbian and Hungarian poet, translator and lawyer who carried an extensive correspondence with his prominent Hungarian contemporaries as well as Serbian writers and intellectuals. Mihailo's younger brother, Jovan Vitković (1785-1849) served as priest of the Tabán church, and cultivated friendships with Benedek Virág, a Hungarian poet and historian living in Tabán, and Matija Petar Katančić, a Franciscan friar, pioneer archaeologist and Croatian writer.

The housing stock of the Tabán gradually improved in the 19th century, especially after the unification of Pest and Buda in 1873 as Budapest grew into a booming modern capital during the age of the Dual Monarchy. The urban context of the church changed fundamentally between 1898 and 1903 when the central part of the Tabán was rebuilt creating new roads and squares, demolishing the poorest quarters and even building a new bridge across the Danube.[8]

20th century and destruction

In 1933-1934 the biggest part of the Tabán district was demolished by the municipality of Budapest but the church, which was still in use by the Eparchy of Buda, was preserved. The 1934 urban plan of the municipality foresaw the creation of a sunken courtyard around the church and a row of arches on the side of the planned new thoroughfare.[9] However in the following years the new Tabán Park was created on the site of the demolished district, and the excavated Tabán ruins were incorporated into the design of the green area. The last buildings around the church, including a large block of flats owned by the Serbian parish and the old parish house were demolished in 1938.[10] In the last ten years of its existence the church had a parklike setting as almost every traces of the former Rácváros disappeared due to the large-scale demolitions. The Serbian Orthodox population in the area was also greatly reduced following these changes.

The building was seriously damaged in the siege of Budapest in 1944-45. The Rococo spire and the roof was destroyed, and parts of the vault fell down but the interior and the iconostasis survived the destruction. The liturgical objects and later the paintings were saved by the last parish priest, Vujicsics Dusán (Dušan Vujičić). Although the church was not fit for use, the priest strongly opposed its demolition.[11] In early 1946 György Zubkovics (Georgije Zubković), the Bishop of Buda asked the government for help but the municipality and the Fővárosi Közmunkatanács (Council of Public Works) was against the restoration the church. The urban planners at the time regarded the cathedral obsolete and a hindrance to the intended restructuring of the bridgehead area.[12]

The ruined church was finally demolished in 1949. The area was landscaped but a little more than ten years later it was completely restructured again when the new Elisabeth Bridge was built. In 1962 new roads and a traffic interchange was built covering the land where the cathedral had stood. In 2014 a memorial bell was erected nearby which was created by Kristóf Petrika and László Rétháti. The bell is decorated with the coat-of-arms of the Eparchy of Buda and a Serbian inscription recalling the foundation and the destruction of the former Orthodox cathedral.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to St. Demetrius Church (Budapest). |

- Nagy Lajos: Budapest története III. A török kiűzetéstől a márciusi forradalomig, Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest, 1975, p. 129

- Nagy Lajos: Rácok Budán és Pesten (1686-1703), in: Tanulmányok Budapest Múltjából 13., 1959, p. 72

- Szerb székesegyház a Tabánban. Az eltűnt Rácváros emlékezete - Kiállítási vezető (ed. Tamás Csáki), Budapest, 2018, Budapesti Történeti Múzeum, pp. 29-31

- Tóth Árpád: Főnixmadárként feltámadó szakrális tér a budai szerbek püspöki templomából, Műemlékvédelem, 2018/6, p. 448

- Magyar Kurir, 11 September 1810

- Buda nagyméretű kataszteri térképsorozata, 1873 (map)

- Margalits Ede: Szerb történelmi repertorium 1., Budapest, 1918, Szerb évkönyvek, p. 17

- A budai Ráczváros bontása, in: Vasárnapi Ujság, 1898/6, p. 88

- Kempelen Ágoston: Előterjesztés az I. ker. Tabán szabályozási tervének megállapítása ügyében. in: Fővárosi Közlöny, 3 July 1934, pp. 734-735

- Friss Ujság, 20 March 1938, p. 16

- Saly Noémi: "Gyönyörű, kocsmai csend" - A nyolcvan éve lebontott Tabán emlékezete, in: Budapest, 2013 December, p. 25

- Gárdonyi Jenő: Új elgondolások Budapest-fürdőváros kialakítására, Fővárosi Napló, 28 September 1946, p. 2