Chunee

Chunee (or Chuny) was an Indian elephant who was brought to Regency London in 1811.

Three elephants were brought to England in East India Company ships between 1809 and 1811. The third of these was Chunee. He travelled on the East Indiaman, Astell, from Bengal, arriving in England in July 1811.[1]:190

The other two elephants, also owned by Stephani Polito at some point, arrived in England in September 1809,[1]:125 and June 1810.[1]:186

"Mr Polito ... has obtained possession of a remarkably fine Elephant, brought to England in the Hon. East India Company's ship, Winchelsea, Capt. William Moffat, which will be exhibited at Rumsey [sic] fair on Monday; and it is expected he will be offered for public inspection for a day or two, in this town [Winchester], on his way to the Exeter 'Change London."[2]

The second elephant was brought to England from Sri Lanka on the East India Company ship Walthamstow in June 1810.[1]:186

Chunee was originally exhibited at the Covent Garden Theatre,[1]:190 but was bought by circus owner Stephani Polito to join his menagerie at Exeter Exchange on the Strand in London. The menagerie was bought by Edward Cross in 1817. The events in which the elephant was put to death in 1826 became a cause célèbre.

Career

Chunee weighed nearly 7 tons, was 11 feet tall, and was valued at £1,000. He was tame, and was originally a theatrical animal, appearing on stage with Edmund Kean. His plays included Blue Beard, at the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden, and the pantomime Harlequin and Padmanaba, or the Golden Fish, at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane.

Chunee was trained to take a sixpence from visitors to the menagerie to hold with his trunk before returning it. An entry in Lord Byron's journal records a visit to Exeter Exchange on 14 November 1813, when "The elephant took and gave me my money again — took off my hat — opened a door — trunked a whip — and behaved so well, that I wish he was my butler."

Death

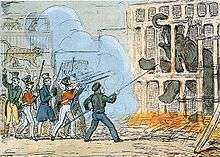

Chunee became dangerously violent towards the end of his life, attributed to an "annual paroxysm" (perhaps his musth) aggravated by a rotten tusk which gave him a bad toothache. On 26 February 1826, while on his usual Sunday walk along the Strand, Chunee ran amok, killing one of his keepers. He became increasingly enraged and difficult to handle over the following days, and it was decided that he was too dangerous to keep. The following Wednesday, 1 March, his keeper tried to feed him poison, but Chunee refused to eat it. Soldiers were summoned from Somerset House to shoot Chunee with their muskets. Kneeling down to the command of his trusted keeper, Chunee was hit by 152 musket balls, but refused to die. Chunee was finished off by a keeper with a harpoon or sword. The floor of his cage was deeply covered with his blood, and it was said that the sound of the elephant in agony was more alarming than the reports of the soldiers’ guns.

Aftermath

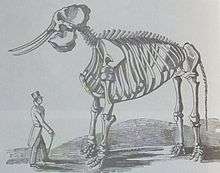

Hundreds of people paid the usual shilling entrance fee to see his carcass butchered, and then dissected by doctors and medical students from the Royal College of Surgeons. His skeleton weighed 876 lb (397 kg), and was sold for £100 and exhibited at the Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly, and later at the Royal College of Surgeons in Lincoln's Inn Fields, the bullet holes clearly visible. His skin weighed 17 cwt (1,900 lb or 860 kg), and was sold to a tanner for £50. Chunee's skeleton was on display in the Hunterian Collection until 1941 when it had a direct hit from a Luftwaffe airstrike.

The manner of Chunee's death was widely publicised, with illustrations printed in popular newssheets of volley after volley being shot into his profusely bleeding body. Recipes were published for elephant stew, along with maudlin poems saying "Farewell, poor Chuny". Letters were printed in The Times protesting at the barbarity of the process, and the poor quality of the living conditions of the animals in the menagerie. The Zoological Society of London was founded in April 1826. The controversy was the inspiration for a successful play at Sadler's Wells, entitled Chuneelah; or, The Death of the Elephant at Exeter 'Change.

The menagerie at Exeter Exchange declined in popularity after Chunee's death. The animals were moved to Surrey Zoological Gardens in 1828, and the building was demolished in 1829.

See also

- List of historical elephants

- Topsy the Elephant

- Tyke

- Mary (elephant)

- Shooting an Elephant

Sources / further reading

- Donald, Diana (2007). A divided nature : the representation of animals in Britain, c.1750-1850. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 171–173. ISBN 0300126794.

External links

- Medal of Chunee at Blackburn Museum

- Exeter Exchange

- Romantic Rhinos and Victorian Vipers: The Zoo as Nineteenth-Century Spectacle by Ashton Nichols

- Cross's Menagerie (includes links to contemporary images)

- Royal College of Surgeons at Victorian London

- Ceramic depiction of Chunee in Stephani Polito's Menagerie

- Destruction of the Furious Elephant of Exeter Change (Lithographic print dated 6 March 1826)

- Destruction of the Noble Elephant (Hand coloured print)

- When Animals Resist their Exploitation by Jason Hribal

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chunee. |

References

- Grigson, Caroline, Menagerie: The History of Exotic Animals in England, Oxford University Press, 2016. ISBN 9780198714705

- Hampshire Chronicle (23 April 1810), p.4.