Chilham Castle

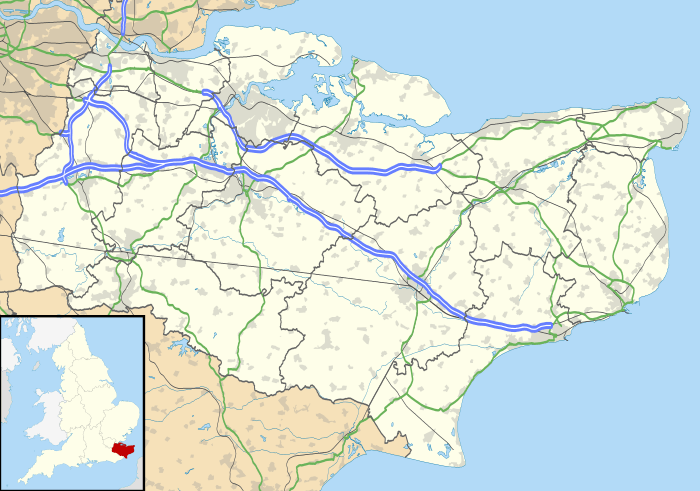

Chilham Castle is a manor house and keep in the village of Chilham, between Ashford and Canterbury in the county of Kent, England.

| Chilham Castle | |

|---|---|

| Chilham, Kent, England | |

| |

Chilham Castle | |

| Coordinates | 51.243°N 0.960°E |

| Type | Manor house and keep |

| Site information | |

| Controlled by | Historic England |

| Condition | Excellent |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1612–1616 |

| Built by | Dudley Digges |

| In use | Private Residence |

| Materials | Brick and Stone |

History

The polygonal keep of the Norman Castle, the oldest building in the village, dates from 1174 and is still inhabited - making it perhaps one of the oldest dwellings in the UK. It was said to have been built for King Henry II. But archaeological excavations carried out in the 1920s suggest that it stands on the foundations of a much older Anglo-Saxon fortification, possibly dating from the seventh century. In June 1320, Chilham Castle was the venue for a splendid reception hosted by Bartholomew de Badlesmere for Edward II and his entourage when they were travelling to Dover en route for France.[1]

The Jacobean building, within sight of the "Old Castle" (the keep), was completed in 1616 for Sir Dudley Digges on a hexagonal plan, with five angled ranges and the sixth left open. It has battlemented parapets, clustered facetted columnar brick chimneys and corner towers with squared ogee cappings.

The Victorian tradition that this bold but vernacular house was designed by Inigo Jones[2] is not credited by architectural historians.[3] Indeed, Nicholas Stone, a master mason who had worked under Jones' direction at Holyrood Palace in 1616, and at the Whitehall Banqueting House, was commissioned to add a funerary chapel to Chilham church for Sir Dudley Digges, to contain Stone's funerary monument to Lady Digges, in 1631–32;[4] if any traces of the manner of Jones were discernible at Chilham Castle, Nicholas Stone might be considered as a candidate.[5] It is, nevertheless, one of the finer mansions in the south-east of England and commands exceptional views across the valley of the River Stour, Kent.

The gardens, said originally to have been laid out by John Tradescant the elder, were redesigned twice in the eighteenth century. First, under the London banker James Colebrooke[6] (who bought the estate from the Digges family) fine vistas were created stretching to the river and then, under Thomas Heron (who acquired the estate from Colebrooke's son Robert),[7] Capability Brown made further recommendations for change, some of which were implemented.

Chilham Castle was purchased by James Wildman in 1794[8] and in 1816 was inherited by his son James Beckford Wildman, who sold it in 1861, because of falling income after emancipation of the slaves on the family estates in the West Indies. Plans of Chilham showing some of the substantial changes made to the building by David Brandon for Charles Hardy in 1862 and by Sir Herbert Baker for mining magnate Sir Edmund and Lady Mary Davis in the early nineteen twenties are conserved in the Victoria & Albert Museum.

The present terracing, altered in the eighteenth and twentieth centuries, leads down to a fishing lake dating from the time of Charles Hardy's son Charles Stewart Hardy in the 1860s and 70s. The walls to the grounds date mostly from the eighteenth century, although the two gatehouses were only added in the early 1920s, again replacing a very different 19th-century one.

From 1949 until his death in 1992 it was owned by the John Whyte-Melville-Skeffington, 13th Viscount Massereene[9] Chilham Castle was owned by UKIP activist Stuart Wheeler, who lived there with his three daughters, Sarah, Jacquetta, and Charlotte until his death on 23 July 2020. Stuart's wife the photographer Tessa Codrington died in 2016.

The site now hosts the Chilham Park Equestrian Centre.

In 1965 it was used for part of the filming of The Amorous Adventures of Moll Flanders starring Kim Novak, Leo McKern and Angela Lansbury. In 1985 Chilham Castle featured in an episode of 1980s police drama Dempsey & Makepeace as Makepeace's family home (filmed summer 1984). The episode was titled 'Cry God For Harry' and most of the hour-long episode was filmed in the castle and its grounds. It also featured in the first episode in 1989 of the ITV adventure game show Interceptor produced by Chatsworth Television who were responsible for the earlier Treasure Hunt series. A medieval joust was being held there and a contestant was required to take part in order to progress further in the show.

In 1994, the castle featured in an episode of Agatha Christie's Poirot (ITV), as Simeon Lee's manor house Gorston Hall. It was also used in the 2006 TV film, "The Moving Finger" (Miss Marple) as the magnificent home of Cardew Pye. The entire village also features.[10]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chilham Castle. |

- Haines, Roy Martin (2003). King Edward II: Edward of Caernarfon His Life, His Reign and Its Aftermath, 1284-1330. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 120.

- Sir Banister Fletcher, A History of Architecture on the Comparative Method (1901:407) listed Chilham among Jones' works, apparently the last historian to do so: "Many buildings have been attributed to Jones with very slight authority. They include Chilham Castle in Kent..." DNB reports (s.v. "Inigo Jones"); George Mabbitt (Mabbitt, "Chilham: The Unique Village," 1999 Archived 2007-07-10 at the Wayback Machine), alludes to original plans in the Royal Institute of British Architects; this is apparently an error, but there is one unsigned outline plan, apparently most ancient, now in the keeping of the Victoria & Albert Museum, London.

- Neither by Howard Colvin, A Biographical Dictionary of British Architects, 1600-1840 3rd ed. (Yale University Press) 1995, who makes no attribution of seventeenth-century Chilham, nor by Nicholas Cooper, Houses of the Gentry, 1480-1680 (Yale University Press) 1999, who discusses Chilham briefly (p. 33) and illustrates both new and old castles (p. 32, figs 19 and 20).

- Colvin 1995, s.v. "Stone, Nicholas"; Stone's chapel was demolished in 1863.

- John Newman, "Nicholas Stone's Goldsmiths' Hall: Design and Practice in the 1630s" Architectural History 14 (1971:30-39, 138-141) discusses Stone's role in the dissemination of Jones' architectural ideas in England.

- One of his sons was Sir James Colebrooke, 1st Baronet.

- Robert's domed mausoleum, designed by Sir Robert Taylor, 1755, attached to the chancel of the parish church, was demolished in 1862 (Colvin 1995, s.v. "Taylor, Sir Robert").

- Edward Hasted, (1778-99) The History and Topographical Survey of the County of Kent.

- ("History - The Owners". The Chilham Castle website. Archived from the original on 2011-08-10. Retrieved 2011-09-01.) states:"In 1949 Chilham was offered for sale by auction with its remaining 400 acres and bought by “Jock“ Skeffington for £94,000. With his wife Annabelle McNamara née Lewis, he lived there until his death in 1992. In 1956 on the death of his father, Skeffington became 13th Viscount Massereene and Baron of Loughneagh, 6th Viscount Ferrard and Baron Oriel of Collon in Ireland and Baron Oriel of Ferrard in the United Kingdom."

- Miss Marple – The Moving Finger (2006), Kent Film Office, retrieved 5 February 2017