Charles I. Barber

Charles Ives[3] Barber (October 25, 1887 – June 14, 1962) was an American architect, active primarily in Knoxville, Tennessee, and vicinity, during the first half of the 20th century. He was cofounder of the firm, Barber & McMurry, through which he designed or codesigned buildings such as the Church Street Methodist Episcopal Church, South, the General Building, and the Knoxville YMCA, as well as several campus buildings for the University of Tennessee and numerous elaborate houses in West Knoxville.[4] Several buildings designed by Barber have been listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Charles I. Barber | |

|---|---|

| Born | Charles Irving Barber October 25, 1887[1] DeKalb, Illinois, US |

| Died | June 14, 1962 (aged 74)[1] |

| Resting place | Greenwood Cemetery, Knoxville[2] |

| Alma mater | University of Pennsylvania[1] |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Spouse(s) | Marion Lawrence (d. 1949), Blanche McKinney[1] |

| Parent(s) | George Franklin Barber and Laura Chenney[1] |

The son of mail-order architect George Franklin Barber, Charles Barber studied at the University of Pennsylvania under Paul Cret, from whom he absorbed the Beaux-Arts style.[4] For most of his career, he primarily designed houses and religious structures, though he also designed schools, clubhouses and courthouses. During the 1930s and 1940s, Barber designed several structures for federal entities such as the Tennessee Valley Authority and the Civilian Conservation Corps.[4]

Biography

Early life and career

Barber was born in DeKalb, Illinois, in 1887, though his parents relocated to Knoxville, Tennessee, when he was about a year old. He attended Knoxville's Baker-Himel School, and briefly attended the University of Tennessee.[1] In 1907, his father sent him on a tour of Greece and Italy, and sought his advice on the proper design of Italian villas, which he used to remodel the home of General Lawrence Tyson (now UT's Tyson Alumni House) that same year.

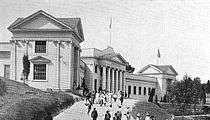

In 1909, Barber enrolled in the University of Pennsylvania. He studied under French-born architect Paul Cret, who was responsible for teaching the Beaux-Arts style to several notable architects in the early 20th century.[4] The Beaux-Arts style would characterize much of Barber's early work. After receiving his Certificate of Proficiency in Architecture in 1911, he returned to Knoxville.[1] Barber's first major work was the Southern States Building, which he designed for the National Conservation Exposition in 1913.[4] During this same period, he formed a partnership with Dean Parmelee (son of his father's partner, Martin Parmelee) to design Knoxville's First Christian Church, which was completed in 1914.[1]

Barber & McMurry

In 1915, Barber, along with his cousin, David West Barber, and fellow Penn alumnus, Benjamin McMurry (1885–1969), founded the firm Barber & McMurry.[1] The firm's early work focused on houses for affluent Knoxvillians in the Sequoyah Hills area, such as the homes of White Lily Flour founder J. Allen Smith (1915) and financier William Cary Ross (1921), both on Lyons View Pike, and the home of Alexander Bonnyman (1916) on Kingston Pike.[4]

During the 1920s and early 1930s, Barber & McMurry designed some of Knoxville's most notable public and religious structures, including the Church Street Methodist Church Episcopal Church South (1931), the Knoxville YMCA (1927), the Candoro Marble Works showroom (1923), the Holston Hills Country Club (1927), and Barber's lone high-rise, the 15-story General Building (1926). The firm also designed several buildings surrounding Ayres Hall atop the "Hill" at UT, most notably the Hoskins Library, Hesler Hall and Dabney Hall.[5]

Barber & McMurry designed some of Knoxville's most elaborate houses in the late 1920s. These include Glen Craig (1926),[6] built for Candoro Marble Works owner John C. Craig, Westcliff (1928), built for inventor Weston M. Fulton,[6] and the H.M. Goforth House (1928) on Lyons View Pike.[4] The latter design was awarded the gold medal at the Southern Architecture and Industrial Arts Exposition in 1929.[4][7]

During the 1930s, Barber turned his attention to the design of public buildings and houses for various federal entities that had begun operating in East Tennessee. Barber worked with fellow architects Roland Wank and Louis Grandgent for the Tennessee Valley Authority's Norris project, and succeeded Wank as chief architect of the project in 1934.[8] Barber's firm also designed the Riverdale School (1938) in eastern Knox County[9] and the headquarters for the Great Smoky Mountains National Park (1940),[10] both built by the Civilian Conservation Corps. In the 1940s and 1950s, Barber and McMurry designed several buildings for the Arrowmont campus in Gatlinburg.[11]

Legacy

Barber died in 1962, and is buried in the Barber family plot in Knoxville's Greenwood Cemetery.[1] In 1976, Barber & McMurry's work was the subject of an exhibition at Knoxville's Dulin Art Gallery.[1] The firm, which currently operates under the name BarberMcMurry, has since transitioned to larger-scale development projects.[7]

At his height, Barber was considered the leading practitioner of the Beaux-Arts style in the South.[4] Several of Barber's designs have been listed on the National Register of Historic Places, either individually or as contributing properties in historic districts. Many of his surviving houses in West Knoxville have been given historic overlay protection by the Knox County Historic Zoning Commission.[4] Notable losses include Westcliff (demolished 1967), the William Cary Ross House (demolished 1969), the Goforth House (demolished 1982),[4] and the J. Allen Smith House (demolished 2004).[12]

Works

Houses

Barber's residential designs typically consisted of Beaux-Arts elements incorporated into traditional architectural styles, such as Tudor, Gothic, or Renaissance.[4] While his works bear little stylistic resemblance to his father's Late Victorian and Colonial houses, his designs reveal an emphasis on proportion and harmony with nature that characterized his father's architectural philosophy.[4][13] In a typical Charles Barber house, chimneys and fireplaces are emphasized, openings are richly ornamented, and materials for roofs and walls are carefully chosen for color and texture.[4]

Three houses constructed on Lyons View Pike in Knoxville illustrate Barber's range of style. The J. Allen Smith House (1915), one of Barber's earliest residential designs, was a primarily Italian Renaissance design, and featured two large chimneys, a tiled roof, and arched loggias.[4] The N.E. Logan House (1929) is a Tudor-style home built to resemble an English Cotswold Cottage, with fieldstone and cedar exterior, thick walls and solid pine interior doors.[4] The Hal Mebanes House (1931), which stands adjacent to the Logan house, is built in the Georgian Revival style, with brick veneer walls, cedar shingles, marble arched entrance, and a rear loggia looking out over the Tennessee River and the mountains beyond.[4]

Westcliff, Fulton's mansion, was one of Barber's largest domestic undertakings. The house's design, a mixture of Gothic, Renaissance, and Baroque influences, was consistently modified as Fulton continuously changed his preferences.[6] The exterior walls were sheathed in crab orchard stone on the lower floors and stucco on the upper floors, all under a tiled roof. The roof contained a garden flanked by an imposing domed gazebo.[6] The interior consisted of vaulted corridors connected by octagonal lobbies, with arcaded loggias on the west and south sides.[6] An elevator accessed a third-story ballroom and the roof garden.[6]

Churches

Barber designed or codesigned over 50 churches in his career.[14] His earliest church, the First Christian Church (1914) on Fifth Avenue, contains Neoclassical and Romanesque elements.[15] The church's dominant feature is its projecting pedimented portico, which is supported by Ionic columns. In 1929, Barber designed adjacent Sunday school and office buildings for the church, as well as a central courtyard with arcaded walkways connecting the three buildings. All three buildings are now contributing properties in the Emory Place Historic District.[15]

Barber's grandest church design is the Gothic-style Church Street Methodist Church (1931), which was codesigned with New York architect John Russell Pope. The church, the congregation of which Barber was a member,[1] features an imposing bell tower, central courtyard, and interior arcades.[16] The respective roles of Barber and Pope in the church's design are unknown.[16] Other churches designed by Barber in the Gothic style, though on a much smaller scale, include the First Methodist Church in Gatlinburg and Barton Chapel in the Robbins community of Scott County.

Other buildings

Barber's lone high-rise, the Second Renaissance Revival-style General Building (commonly called the First Bank Building after its current anchor tenant), was completed in 1926. The first three stories of the building's South Market and Church Avenue facades are coated in limestone veneer, with three monumental arched openings facing South Market.[17] The building's first-floor bank lobby, which includes a mezzanine and vaulted ceilings, is the most impressive interior feature. Barber & McMurry's offices were located in the building from its completion until 1934.[17]

Barber and McMurry designed several school buildings, most notably the Riverdale School in east Knox County and the Sequoyah Elementary School in Sequoyah Hills, the latter of which is still in use (though it has been expanded).[7] For buildings designed for the University of Tennessee in the early 1930s, the firm used a modified "campus" Gothic style to match Ayres Hall, which stands at the center of the "Hill."[5]

In 1923, Barber designed a showroom and garage for the Candoro Marble Works. The showroom is built of marble blocks, and contains extensive marble ornamentation.[18] Barber also designed the adjacent Spanish Colonial-style garage, which features a tiled roof and exterior walls that consist of marble and stucco.[18] Other Barber works include the Holston Hills Country Club (1927), the Christenberry Clubhouse (1936), and the Colonial-style Ossoli Circle Clubhouse (1933). One of Barber's simplest works was the Smoky Mountain Hiking Club Cabin, which the club (of which Barber was a member) assembled in 1934 from the logs of a dismantled pioneer cabin.[19]

References

- East Tennessee Historical Society, Lucile Deaderick (ed.), Heart of the Valley: A History of Knoxville, Tennessee (Knoxville, Tenn.: East Tennessee Historical Society, 1976), pp. 491-492.

- Charles Irving Barber at Findagrave.com. Retrieved: 17 May 2011.

- Many sources, including the University of Tennessee ("Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-09-27. Retrieved 2011-05-17.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)), Deaderick (Heart of the Valley), and the 1909-1910 student directory for the University of Pennsylvania list his middle name as "Irving," but in his later life, Barber himself gave it as "Ives."

- Knoxville Historic Zoning Commission, Lyons View Pike Historic District Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine, c. 2002. Retrieved: 16 May 2011.

- Carroll Van West, Tennessee's Historic Landscapes: A Traveler's Guide (Knoxville, Tenn.: The University of Tennessee Press, 1995), p. 79.

- William Ross McNabb, "Westcliff: Mr. Fulton's Mansion," East Tennessee Historical Society Publications, No. 49 (1977), pp. 93-98.

- Katherine Wheeler, Barber & McMurry Architects, Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture, 2002. Retrieved: 16 May 2011.

- Tim Culvahouse, The Tennessee Valley Authority: Design and Persuasion (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2007), pp. 1924, 1930.

- The Riverdale School: The Restoration Archived August 26, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved: 16 May 2011.

- Lois Reagan Thomas, Headquarters to be Restored to its Original Glory, Knoxnews.com, 16 March 2009. Retrieved: 16 May 2011.

- Susan Knowles and Carroll Van West, National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form for Settlement School Dormitories and Dwellings Historic District, 30 October 2006.

- Knox Heritage: J. Allen Smith Endangered Properties Fund Archived July 26, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved: 19 May 2011.

- Michael Tomlan, Introduction to George F. Barber's Victorian Cottage Architecture: An American Catalog of Designs, 1891 (Dover Publications, 2004), pp. v-xvi.

- William Scott Downs, Encyclopedia of American Biography, Vol. 35 (American Historical Company, 1966), p. 657.

- Ann Bennett, National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form for Emory Place Historic District, May 1994.

- Knoxville Historic Zoning Commission, Church Street Methodist Church National Register Nomination Summary, December 2008. Retrieved: 17 May 2011.

- Cynthia Whitaker, National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form for the General Building, 12 September 1987.

- Tony VanWinkle, National Register of Historic Places Registration Form for Candoro Marble Works Showroom and Garage, 13 July 2004.

- Robbie Jones, The Historic Architecture of Sevier County, Tennessee (Sevierville, Tenn.: Smoky Mountain Historical Society, 1997), pp. 109, 353.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charles Irving Barber. |