Charles Grandison Finney

Charles Grandison Finney (August 29, 1792 – August 16, 1875) was an American Presbyterian minister and leader in the Second Great Awakening in the United States. He has been called The Father of Modern Revivalism.[1] Finney was best known as a flamboyant revivalist preacher during the period 1825–1835 in upstate New York and Manhattan, an opponent of Old School Presbyterian theology, an advocate of Christian perfectionism, and a religious writer.

Charles Grandison Finney | |

|---|---|

| |

| 2nd President of Oberlin College | |

| In office 1851 – 1866 | |

| Preceded by | Asa Mahan |

| Succeeded by | James Fairchild |

| Personal details | |

| Born | August 29, 1792 Warren, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Died | August 16, 1875 (aged 82) Oberlin, Ohio, U.S. |

| Spouse(s) | Lydia Root Andrews (m. 1824) Elizabeth Ford Atkinson (m. 1848) Rebecca Allen Rayl (m. 1865) |

| Profession | Presbyterian minister; evangelist; revivalist; author |

| Signature | |

Together with several other evangelical leaders, his religious views led him to promote social reforms, such as anti-slavery and equal education for women and African Americans. From 1835 he taught at Oberlin College of Ohio, which accepted students without regard to race or sex. He served as its second president from 1851 to 1865, during which its faculty and students were activists for abolition, the Underground Railroad, and universal education.

Biography

Early life

Born in Warren, Connecticut, August 29, 1792,[2] Finney was the youngest of nine children. The son of farmers who moved to the upstate frontier of Jefferson County, New York, after the American Revolutionary War, Finney never attended college. His leadership abilities, musical skill, six-foot three-inch stature, and piercing eyes gained him recognition in his community.[3] He and his family attended the Baptist church in Henderson, New York, where the preacher led emotional, revival-style meetings. Both the Baptists and Methodists displayed fervor through the early nineteenth century.[4] He "read the law", studying as an apprentice to become a lawyer under Benjamin Wright.[5] In Adams he entered the congregation of George Washington Gale, and became director of the church choir.[6]:8 After a dramatic conversion experience and baptism into the Holy Spirit he gave up legal practice to preach the gospel.[7][8]

As a young man Finney was a Master Mason, but after his conversion, he dropped the group as antithetical to Christianity. He was active in Anti-Masonic movements.[9]

In 1821, Finney started studies at age 29 under George Washington Gale, to become a licensed minister in the Presbyterian Church. As did his teacher Gale, he

"took a commission for six months of a Female Missionary Society, located in Oneida County. I went into the northern part of Jefferson County and began my labors at Evans' Mills, in the town of Le Ray."[10]

When Gale moved to a farm in Western, Oneida County, New York, Finney accompanied him, working on Gale's farm in exchange for instruction, a forerunner of Gale's Oneida Institute. He had many misgivings about the fundamental doctrines taught in Presbyterianism.[11] He moved to New York City in 1832, where he was minister of the Chatham Street Chapel and took the breathtaking step of barring from communion all slave owners and traders.[12]:29[4] Since the Chatham Street Chapel was not a church, but a theater "fitted up" to serve as a church, in 1836 a new Broadway Tabernacle was built for him, "the largest Protestant house of worship in the country".[13]:22 In 1835, he became the professor of systematic theology at the newly formed Oberlin Collegiate Institute in Oberlin, Ohio.[14]

Revivals

Finney was active as a revivalist from 1825 to 1835 in Jefferson County and for a few years in Manhattan. In 1830-31, he led a revival in Rochester, New York that has been noted as inspiring other revivals of the Second Great Awakening.[15] A leading pastor in New York who was converted in the Rochester meetings gave the following account of the effects of Finney's meetings in that city: "The whole community was stirred. Religion was the topic of conversation in the house, in the shop, in the office and on the street. The only theater in the city was converted into a livery stable; the only circus into a soap and candle factory. Grog shops were closed; the Sabbath was honored; the sanctuaries were thronged with happy worshippers; a new impulse was given to every philanthropic enterprise; the fountains of benevolence were opened, and men lived to good."[16]

He was known for his innovations in preaching and the conduct of religious meetings, which often impacted entire communities. These included having women pray out loud in public meetings of mixed sexes; development of the "anxious seat", a place where those considering becoming Christians could sit to receive prayer; and public censure of individuals by name in sermons and prayers.[17] He was also known for his extemporaneous preaching.

Finney "had a deep insight into the almost interminable intricacies of human depravity. ...He poured the floods of gospel love upon the audience. He took short-cuts to men's hearts, and his trip-hammer blows demolished the subterfuges of unbelief."[18]:39

Disciples of Finney were Theodore Weld, John Humphrey Noyes, and Andrew Leete Stone.

Antislavery work and Oberlin College presidency

In addition to becoming a widely popular Christian evangelist, Finney was involved with social reforms, particularly the abolitionist movement. Finney frequently denounced slavery from the pulpit, calling it a "great national sin", and he refused Holy Communion to slaveholders.[19]

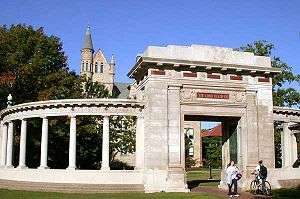

In 1835, the wealthy silk merchant and benefactor Arthur Tappan (1786-1865) offered financial backing to the newly founded Oberlin Collegiate Institute (as Oberlin College was known before 1850), and he invited Finney, on the recommendation of abolitionist Theodore Dwight Weld (1803-95), to establish its theological department. After much wrangling, Finney accepted, on the conditions that he be allowed to continue to preach in New York, that the school admit blacks, and that free speech be guaranteed at Oberlin. After more than a decade, he was selected as its second president, serving from 1851 to 1866. (He had already served as acting President in 1849.)[20] Oberlin was the first American college to accept women and blacks as students in addition to white men. From its early years, its faculty and students were active in the abolitionist movement. They participated together with people of the town in biracial efforts to help fugitive slaves on the Underground Railroad, as well as to resist the Fugitive Slave Act.[21] Many slaves escaped to Ohio across the Ohio River from Kentucky, making the state a critical area for their passage to freedom.

Personal life

Finney was twice a widower and married three times. In 1824, he married Lydia Root Andrews (1804–1847) while living in Jefferson County. They had six children together. In 1848, a year after Lydia's death, he married Elizabeth Ford Atkinson (1799–1863) in Ohio. In 1865 he married Rebecca Allen Rayl (1824–1907), also in Ohio. Each of Finney's three wives accompanied him on his revival tours and joined him in his evangelistic efforts.

Finney's great-grandson, also named Charles Grandison Finney, became a famous author.

Theology

Finney was a New School Presbyterian, and his theology was similar to that of Nathaniel William Taylor. Finney departed from traditional Calvinist theology by teaching that people have free will to choose salvation. He argued that original sin was a "selfishness" that people can overcome if they made themselves a "new heart". He taught that "Sin and holiness are voluntary acts of mind."[22] He also believed that preachers had important roles in producing revival, writing in 1835 that "A revival is not a miracle, or dependent on a miracle, in any sense. It is a purely philosophical result of the right use of the constituted means."[22]

A major theme of his preaching was the need for conversion. He also focused on the responsibilities that converts had to dedicate themselves to disinterested benevolence and work to build the kingdom of God on earth. Finney's eschatology was postmillennial, meaning he believed the Millennium (a thousand-year reign of true Christianity) would begin before Christ's Second Coming. Finney believed Christians could bring in the Millennium by ridding the world of "great and sore evils". Frances FitzGerald writes that "In his preaching the emphasis was always on the ability of men—and women—to choose their own salvation, to work for the general welfare, and to build a new society."[23]

Finney was an advocate of perfectionism, the doctrine that through complete faith in Christ believers could receive a "second blessing of the Holy Spirit" and reach Christian perfection (a higher level of sanctification). For Finney, this meant living in obedience to God's law and loving God and one's neighbors. This was not a sinless perfection. For Finney, even sanctified Christians were susceptible to temptation and capable of sin. Finney believed it was possible for Christians to backslide and lose their salvation.[24]

Benjamin Warfield, a Calvinist professor of theology at Princeton Theological Seminary, claimed that "God might be eliminated from it [Finney's theology] entirely without essentially changing its character."[25] Albert Baldwin Dod, another Old School Presbyterian, reviewed Finney's 1835 book Lectures on Revivals of Religion.[26] He rejected it as theologically unsound.[27] Dod was a defender of Old School Calvinist orthodoxy (see Princeton Theology) and was especially critical of Finney's view of the doctrine of total depravity.[28]

In popular culture

In Charles W. Chesnutt's short story "The Passing of Grandison" (1899), published in the collection The Wife of His Youth and Other Stories of the Color Line, the enslaved hero is named "Grandison", likely an allusion to the well-known abolitionist.[29]

The Charles Finney School was established in Rochester, New York in 1992.

See also (influenced by Finney)

- Manie Payne Ferguson

- Theodore Pollock Ferguson

- Keith Green

- Joshua Hall McIlvaine

- Nathaniel William Taylor

References

- Hankins, Barry (2004), The Second Great Awakening and the Transcendentalists, Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, p. 137, ISBN 0-313-31848-4.

- Charles Finney, Ohio History Central, retrieved July 31, 2019.

- "I. Birth and Early Education", Memoirs of Charles G. Finney, Gospel truth, 1868.

- Perciaccante, Marianne (2005), Calling Down Fire: Charles Grandison Finney and Revivalism in Jefferson County, New York, 1800–1841, pp. 2–4.

- Bourne, Russell. Floating West. W. W. Norton. 1992. p. 177

- Fletcher, Robert Samuel (1943). History of Oberlin College from its foundation through the Civil War. Oberlin College.

- "III. Beginning of His Work", Memoirs, Gospel truth, 1868.

- "III. Beginning of His Work", Memoirs, Gospel truth, 1868.

- Charles E. Hambrick-Stowe, Charles G. Finney and the Spirit of American Evangelicalism (1996), p. 112

- Finney, Charles G. (1989) [1868]. "Chapter V. I Commence Preaching as a Missionary". In Rosell, Garth M.; Dupuis, A. G. (eds.). The Original Memoirs of Charles Finney. Retrieved September 3, 2019.

- "IV. His Doctrinal Education and Other Experiences at Adams", Memoirs, Gospel truth, 1868.

- Essig, James David (March 1978). "The Lord's Free Man: Charles G. Finney and His Abolitionism". Civil War History. 24 (1). pp. 25–45. doi:10.1353/cwh.1978.0009.

- Barnes, Gilbert Hobbs (1964). The antislavery impulse, 1830–1844. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World.

- Hyatt, Eddie (2002), 2000 Years Of Charismatic Christianity, Lake Mary, FL: Charisma House, p. 126, ISBN 978-0-88419-872-7.

- William, Cossen. "Charle's Finney's Rochester Revival". Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- Hyatt, 126

- The various types of new measures are identified mostly by sources critical of Finney, such as Bennet, Tyler (1996), Bonar, Andrew (ed.), Asahel Nettleton: Life and Labors, Edinburgh: Banner of Truth Trust, pp. 342–55; Letters of Rev. Dr. [Lyman] Beecher and the Rev. Mr. Nettleton on the New Measures in Conducting Revivals of Religion with a Review of a Sermon by Novanglus, New York: G&C Carvill, 1828, pp. 83–96; and Hodge, Charles (July 1833), "Dangerous Innovations", Biblical Repertory and Theological Review, 5, University of Michigan, pp. 328–33, retrieved March 31, 2008.

- Wishard, S. E. (1890). "Historical Sketch of Lane Seminary from 1853 to 1856". Pamphlet souvenir of the sixtieth anniversary in the history of Lane Theological Seminary, containing papers read before the Lane Club. Cincinnati: Lane Theological Seminary. pp. 30–40.

- FitzGerald, Frances (2017). The Evangelicals: The Struggle to Shape America. Simon and Schuster. p. 40. ISBN 1439131333.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- {{cite web|title=Charles Grandison Finney Papers | url=http://oberlinarchives.libraryhost.com/index.php?p=collections/controlcard&id=85/%7Cwork=Oberlin College Archives|publisher=Oberlin College|accessdate=30 April 2020|url}

- Charles E. Hambrick-Stowe, Charles G. Finney and the Spirit of American Evangelicalism (1996) p 199

- FitzGerald 2017, p. 36.

- FitzGerald 2017, p. 37.

- FitzGerald 2017, p. 44.

- B. B. Warfield, Perfectionism (2 vols.; New York: Oxford, 1931) 2. 193.

- "On Revivals of Religion" Archived July 20, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Biblical Repertory and Theological Review Vol. 7 No. 4 (1835) p.626-674

- Charles E. Hambrick-Stowe, Charles G. Finney and the Spirit of American Evangelicalism, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1996. ISBN 0-8028-0129-3, p.159

- Rev. Albert B. Dod, D.D., "On Revivals of Religion", in Essays, Theological and Miscellaneous, Reprinted from the Princeton Review, Wiley and Putnam (1847) pp.76-151

- Cutter, Martha J. "Passing as Narrative and Textual Strategy in Charles Chesnutt's 'The Passing of Grandison'", Passing in the Works of Charles W. Chesnutt, Eds. Wright, Susan Prothro, and Ernestine Pickens Glass. Jackson, MS: Mississippi UP, 2010, p. 43. ISBN 978-1-60473-416-4.

Further reading

- Martin, John H. (Fall 2005). "Charles Grandison Finney. New York Revivalism in the 1820-1830s". Crooked Lake Review. Retrieved August 10, 2019.

- Perciaccante, Marianne. Calling Down Fire: Charles Grandison Finney and Revivalism in Jefferson County, New York, 1800-1840 (2005)

- Guelzo, Allen C. "An heir or a rebel? Charles Grandison Finney and the New England theology," Journal of the Early Republic, Spring 1997, Vol. 17 Issue 1, pp 60–94

- Hambrick-Stowe, Charles E. Charles G. Finney and the Spirit of American Evangelicalism (1996), a major scholarly biography

- Rice, Sonja (1992). Educator and Evangelist : Charles Grandison Finney, 1792-1875. Oberlin College Library. OCLC 26647193.

- Hardman, Keith J. Charles Grandison Finney, 1792-1875: Revivalist and Reformer (1987), a major scholarly biography

- Johnson, James E. "Charles G. Finney and a Theology of Revivalism," Church History, September 1969, Vol. 38 Issue 3, pp 338–358 in JSTOR

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Charles Grandison Finney |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Charles Grandison Finney |

| Wikisource has the text of an 1879 American Cyclopædia article about Charles Grandison Finney. |

- The Theology of C. G. Finney explained and defended

- "The COMPLETE WORKS of CHARLES G. FINNEY", collected by Gospel Truth Ministries

- A biography of Charles Finney by G. Frederick Wright (Holiness perspective; supportive)

- A Vindication of the Methods and Results of Charles Finney's Ministry (Revivalist perspective; supportive; answers many traditional Old School Calvinist critiques)

- Charles Grandison Finney: New York Revivalism in the 1820-1830s by John H. Martin, Crooked Lake Review

- Articles on Finney (conservative Calvinist perspective; critical)

- How Charles Finney's Theology Ravaged the Evangelical Movement (conservative Calvinist perspective; critical)

- "The Legacy of Charles Finney" by Dr. Michael S. Horton (conservative perspective; critical)

- The Oberlin Heritage Center-Local history museum and historical society of Oberlin, OH, where Finney lived and worked for decades.

- Finney's Lectures on Theology by Charles Hodge (conservative Calvinist perspective; critical)

- The Church in Crisis A critical look at Finney's revivalist methods and their impact on the modern church in America

- . Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.