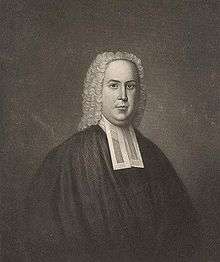

Charles Chauncy

Charles Chauncy (baptised November 5, 1592 – February 19, 1672) was an Anglo-American clergyman, educator, and secondarily, a physician.[2]

Charles Chauncy | |

|---|---|

| |

| President of Harvard College | |

| In office 1654–1672 | |

| Preceded by | Henry Dunster |

| Succeeded by | Leonard Hoar |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Ardeley (then known as Yardley),[1] Hertfordshire |

| Died | February 19, 1672 (aged 79) Cambridge, Massachusetts |

Life

Charles Chauncy was born at Ardeley, Hertfordshire, England.[3] The village was then known as Yardley. The manor belonged to the Dean and Chapter of St Paul's Cathedral, which leased the manor-house (a moated property called "Ardeley Bury") and the demesne lands to the Chauncy family.[4]

He was educated at Westminster School,[5] then at Trinity College, Cambridge,[6] where he later was a lecturer in Greek. In 1627 the College arranged for him to be appointed vicar of St Mary's Church, Ware. In 1633 he left Ware to become vicar of Marston St. Lawrence. At both parishes he faced disciplinary procedures for his Puritan views which included opposition to communion rails.[3]

He emigrated to America in 1637.[1] He preached at Plymouth until 1641,[1] then at Scituate where, says Mather, "he remained for three years and three times three years, cultivating the vineyard of the Lord." He was appointed president of Harvard College in 1654.[1] He held that office until his death in 1671. His descendants also include Connecticut Governor and National Baseball Hall of Fame member, Morgan Bulkeley.[7] Besides a number of sermons, Chauncy published The Doctrine of the Sacrament, with the Right Use Thereof (1642); The Plain Doctrine of the Justification of a Sinner in the Sight of God (1659), a collection of 26 sermons; and Antisynodalia Scripta Americana (1662).

During his time at Plymouth and Scituate, Chauncy got into a heated debate with the religious and secular leaders of the Plymouth Colony over the issue of baptism. Chauncy taught that only baptism by full immersion was valid, while the Separatist Elders taught that sprinkling water over the body was just as valid. The sprinkling method of baptism was much preferred in New England due to its cooler and harsher climate. The religious leaders of the Plymouth Colony held public debates, trying to convince Chauncy to change his views. When Chauncy still did not change his views, the Pilgrim leaders wrote to congregations in Boston and New Haven soliciting their views, and all the congregations wrote back that both forms of baptism were valid. Still, Chauncy did not change his teachings. It was because of this issue that Chauncy left Plymouth for Scituate in 1641. A year after arriving in Scituate, Chauncy had a chance to practice what he preached, when he publicly baptized his twin sons by full immersion. The plan backfired when one of his sons passed out due to being dunked in the water. The mother of the child who was supposed be baptized at the same event refused to let it happen, and according to John Winthrop, got a hold of Chauncy and "near pulled him into the water". When Chauncy was hired to be President of Harvard, he had to promise the leaders in Boston that he would keep his views on baptism quiet.

He died on 19 February 1672[1] and was buried at New Cambridge.[8]

Family

Chauncy married at Ware on 17 March 1630 Catherine, daughter of Robert Eyre, barrister-at-law, of Salisbury, Wiltshire. By her, who died on 24 Jan. 1668, aged 66, he had six sons, all bred to the ministry and graduates of Harvard, and two daughters.[8]

His great-grandson was also named Charles Chauncy (1705–1787),[1] minister of the First Church (Congregational) of Boston 1727–1787, an Old-Light opponent of Jonathan Edwards and the New Light ministers of the Great Awakening, and a precursor of Unitarianism.

Sir Henry Chauncy (1632-1719), the historian, was his grandnephew.

Literature

- Cotton Mather, Magnalia (London, 1702)

- Fowler, Memorials of the Chaunceys (Boston, 1858)

- William Bradford, Of Plymouth Plantation

- John Winthrop, Journal of John Winthrop

References

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 18–19.

-

- “Chauncy, Charles (bap. 1592, d. 1672),” Francis J. Bremer in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, eee online ed., ed. David Cannadine, Oxford: OUP, 2004, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/5196 (accessed July 18, 2017).

- "Ardeley Bury". Retrieved 2017-07-25.

- ""Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-01-13. Retrieved 2015-02-19.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)"

- "Chauncey, Charles (CHNY610C)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- Norton, Frederick Calvin (1905). The Governors of Connecticut. Connecticut Magazine Co. LCC F93.N88. Retrieved 2006-12-29.

- Goodwin 1887.

- Attribution

![]()

External links

| Academic offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Henry Dunster |

President of Harvard College 1654–1672 |

Succeeded by Leonard Hoar |