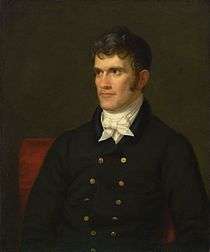

Charles Bird King

Charles Bird King (September 26, 1785 – March 18, 1862) was an American portrait artist, best known for his portrayals of significant Native American leaders and tribesmen.

Charles Bird King | |

|---|---|

Self-portrait, aged 70 | |

| Born | September 26, 1785 |

| Died | March 18, 1862 (aged 76) Washington D.C. |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Edward Savage in New York, and Benjamin West at the Royal Academy in London |

| Known for | Painting, including portraiture, still life, and genre |

Notable work | Native American portraiture commissioned by the United States Government from 1822 to 1842 |

| Patron(s) | John Quincy Adams, John Calhoun, Henry Clay, James Monroe, Daniel Webster and William Henry Tayloe |

Biography

Charles Bird King was born in Newport, Rhode Island, the only child of Deborah (nee Bird) and Zebulon King, an American Revolutionary veteran and captain. The family traveled west after the war, but when King was four years old, his father was killed and scalped by Native Americans near Marietta, Ohio. Because of this, Deborah King took her young son and moved back to her parents' home in Newport.[1]

When King was fifteen, he went to New York to study under the portrait painter Edward Savage. At age twenty he moved to London to study under Benjamin West at the Royal Academy. After a seven-year stay in London, King returned to the U.S. due to the War of 1812. He lived and worked in the major cities of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Baltimore, Maryland; and Richmond, Virginia.

He eventually settled in Washington, DC, due to the economic appeal of the burgeoning capital city. Here King developed a solid reputation as a portraitist among politicians, and earned enough to maintain his own studio and gallery.[2] King’s economic success in the art world, particularly in the field of portraiture, was in part dependent on his ability to socialize with the wealthy celebrities, and relate to the well-educated politicians of the time: "His industry and simple habits enabled him to acquire a handsome competence, and his amiable and exemplary character won him many friends".[3] These patrons included such prominent leaders as John Quincy Adams, John C. Calhoun, Henry Clay, James Monroe, and Daniel Webster.[4] King’s popularity and steady stream of work left him with little reason or need to leave Washington.[3] In 1827 he was elected to the National Academy of Design as an Honorary Academician.

King never married. He lived in Washington until his death on March 18, 1862. He bequeathed his collection of paintings, books, and prints to the Redwood Library and Athenaeum.

Styles and influences

Though King’s legacy lies in his portraiture, throughout his career he also demonstrated a great technical skill in still life, genre, and literary paintings. Scholars have thought he would have preferred to focus on these styles throughout his career, but he needed to earn a living. Painting portraits was the only way for artists to make enough money to live on in the early part of the 19th century.

King's inclination towards genre and still life paintings is thought to have been influenced to his seven-year stay in London. The 16th and 17th-century style attributed to masters in Northern Europe, especially that of the Dutch and Flemish, was quite popular in the upper echelons of the art culture. While attending the Royal Academy, King was swayed towards the Dutch styles by the demand such works commanded. He also was able to study the works and learn from them. It is likely that through his schooling, he was able to study the British royal collection, as “Prince of Wales, and Regent, George IV collected Dutch art voraciously…” and the prints were the favored style at the time by other members of European royalty.

King took more than stylistic cues from these examples, as he also employed some of the techniques which he saw. As Nicholas Clark wrote in 1982, King “sometimes relied upon Dutch prints for formal solutions."[5] The prints were sources of valued composition. Many of King's paintings include features that show the influence of Dutch art. As noted above, King incorporated the techniques of Dutch painting into his portraits, though he recognized that the United States was not yet as familiar with "references to the style as it would be in the sphere of “post-Civil War materialism…[3]".

King is known to have been especially committed to staying within the confines of the traditional style of painting which he learned in his youth: “it is apparent that the artist would adapt, time and again, traditional European mannerisms to his new and native subject matter”.[3]

While King completed a number of paintings that invoked Dutch painting technique, he is better known as an important figure for his numerous portraits of Native Americans, commissioned by the federal government. He was also commissioned by the government for portraits of celebrated war heroes, and privately by the political elite. Painting was used to portray important men before the time of photography. Despite his popularity at the time, King is often overlooked in the broad scope of art history. His relative obscurity may be due in part to his lack of innovation in his work. It is also surely due to the loss of most of his numerous Indian portraits to a fire in the Smithsonian. With his most unique work destroyed, he was overlooked by succeeding generations.[3]

Native American portraits

The Smithsonian art historian Herman J. Viola notes in the preface to The Indian Legacy of Charles Bird King that he compiled the book in order to acknowledge the importance of King, as well as his Native American subjects, as part of the creation of a federal collection of Indian portraits. The government, private collectors, and museums hold portraits by a number of talented United States’ painters, including George Catlin, James Otto Lewis, and George Cooke. King’s work makes up a bulk of the Indian portrait collection, with more than 143 paintings done from 1822 to 1842.[6]

Thomas McKenney, who served as the United States superintendent of Indian trade in Georgetown and later as the head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, initiated the government's commissioning of the portraits. Like many others, at the time he believed that the indigenous people were nearing extinction, and he was seeking ways to preserve their history and culture. He first tried to collect artifacts from various tribes, then thought of having portraits painted for the government. About this time, he met King, whose talent he appreciated. “The arrival of Charles Bird King on the Washington scene inspired the imaginative McKenney to add portraits to his archives.”[6] King painted the subjects in his own studio, as McKenney easily obtained the consent for the portraits from Native American leaders coming to Washington to do business with the US through his new department. King’s 20-year role in painting works for the collection was profitable for the artist. He charged at least $20 for a bust, and $27 for a full-figure portrait, allowing him to collect an estimated $3,500 from the government.[6]

The portraits gained widespread publicity beyond Washington during this period as McKenney broadened his project by publishing a book on Native Americans. In 1829 he began what would become many years' worth of work on the three-volume work, History of the Indian Tribes of North America.[6] The project featured the many portraits of Native Americans, mostly King's, in lithograph form, accompanied by an essay by the author James Hall.

After the administration changed and McKenney left the BIA, the agency donated the Native American portrait collection to the National Institute, but shoddy care and shoddy displays kept it from the public eye.[6] When the National Institute deteriorated, it gave its work in 1858 to the Smithsonian Institution.[6] King's portraits were displayed among similar paintings by the New York artist John Mix Stanley, in a gallery containing a total of 291 paintings of Native American portraits and scenes. On January 24, 1865 a fire destroyed the paintings in this gallery, though a few of King’s were saved before the flames spread. Representations of many of the lost paintings have been found in McKenney’s lithograph collection that supported the book.

Gallery

Portraits

- Portraits by Charles Bird King

Sarah Weston Seaton, wife of William Winston Seaton, and two of their children, c. 1815

Sarah Weston Seaton, wife of William Winston Seaton, and two of their children, c. 1815 George Washington Adams, c. 1820

George Washington Adams, c. 1820 Elizabeth Meade Creighton, c. 1820

Elizabeth Meade Creighton, c. 1820%2C_Oto_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg) Hayne Hudjihini (Eagle of Delight) Otoe c. 1822

Hayne Hudjihini (Eagle of Delight) Otoe c. 1822 Monchousia (White Plume) Kansa c. 1822

Monchousia (White Plume) Kansa c. 1822%2C_Pawnee_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

%2C_Pawnee_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg) Sharitarish (Wicked Chief) Pawnee c.1822

Sharitarish (Wicked Chief) Pawnee c.1822%2C_Kansa_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg) Shaumonekusse (Prairie Wolf) Otoe c.1822

Shaumonekusse (Prairie Wolf) Otoe c.1822 Vice President John C. Calhoun, 1822

Vice President John C. Calhoun, 1822 First Lady Louisa Adams, c. 1821-1825

First Lady Louisa Adams, c. 1821-1825 David Vann, later Treasurer of the Cherokee Nation, 1825

David Vann, later Treasurer of the Cherokee Nation, 1825 Red Jacket, Sagoyewatha, or Keeper Awake - A Seneca War Chief, c. 1828

Red Jacket, Sagoyewatha, or Keeper Awake - A Seneca War Chief, c. 1828 Novelist and biographer Margaret Bayard Smith, c. 1829

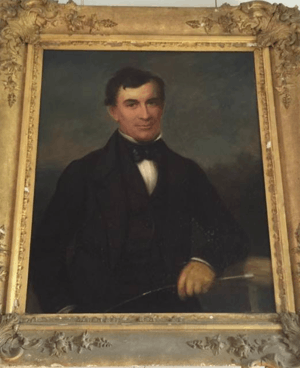

Novelist and biographer Margaret Bayard Smith, c. 1829 Joseph Kent, Governor of Maryland and U.S. senator, before 1837

Joseph Kent, Governor of Maryland and U.S. senator, before 1837 Plantation owner William Henry Tayloe

Plantation owner William Henry Tayloe

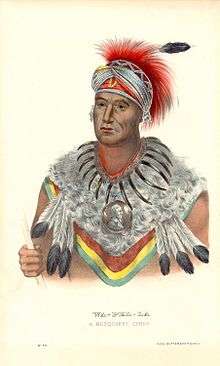

Lithographs of Native Americans

Lithographs from Thomas L. McKenney & James Hall. History of the Indian Tribes of North America. Philadelphia: F.W. Greenough, 1838–1844

- Lithographs of Native Americans by Charles Bird King

Menawa, a Creek chief

Menawa, a Creek chief Ojibwa woman and child

Ojibwa woman and child The Choctaw chief Pushmataha, 1824

The Choctaw chief Pushmataha, 1824 Major Ridge, 1834

Major Ridge, 1834 Tah-Chee (Dutch), A Cherokee Chief

Tah-Chee (Dutch), A Cherokee Chief Tshusick, an Ojibwa woman

Tshusick, an Ojibwa woman

Still life

Exhibitions

- The Annual Exhibition Record of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, August 1813

- Louisville Museum, Louisville, Kentucky, May 1834

- Philadelphia Artists, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, April 8, 1839

- Artists' Fund Society, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1845

- The McKenney & Hall Lithographs of Charles Bird King’s Portraits of American Indians, Smithsonian Institution Building, 1990–1996

Sampling of works

- William Pinkey (1815) Maryland Historical Society

- General John Stricker (1816) Maryland Historical Society

- The Poor Artist’s Cupboard (c. 1815) National Gallery of Art, formerly in the Corcoran Gallery of Art

- Wicked Chief (c.1822) White House Library

- Vanity Of An Artist’s Dream (1830) Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University

- Fruit Piece with Pineapples (1840) John S. H. Russell, Newport, Rhode Island

- Young Omahaw, War Eagle, Little Missouri, and Pawnees (c. 1821) Smithsonian American Art Museum, Smithsonian Institution

- Hoowaunneka [Little Elk], Winnebago, (1828), Peabody Museum, Harvard University.

- Wajechai [Crouching Eagle], (1824), Gulf States Paper Corporation, Tuscaloosa, Alabama.

- Pushmataha, The Sapling is Ready for Him, (1824), Gulf States Paper Corporation Collection, Tuscalossa, Alabama.

- Joseph Porus [Polis], Penobscot, (1842), Thomas Gilcrease Institute of American History and Art, Tulsa, Oklahoma.

See also

- Elbridge Ayer Burbank

- George Catlin

- Seth and Mary Eastman

- Paul Kane

- W. Langdon Kihn

- Joseph Henry Sharp

- John Mix Stanley

References

- Viola, Herman J. The Indian Legacy of Charles Bird King. 1st ed. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1976.

- Viola, Herman J. The Indian Legacy of Charles Bird King 1st ed. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1976.

- Consentino, Andrew J. "Charles Bird King: an Appreciation," American Art Journal 6 (1974): 54–71. JSTOR.

- Truettner, William, ed. "Have a Question?" Smithsonian American Art Museum, Smithsonian Institution Press, 1991 <http://americanartsi.edu>.

- Clark, Nichols B. "A Taste for the Netherlands: the Impact of Seventeenth-Century Dutch and Flemish Genre Painting on American Art 1800-1860," American Art Journal 14 (1982): 29. JSTOR.

- Viola, Herman J. The Indian Legacy of Charles Bird King. 1st ed. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1976.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charles Bird King. |