Paul Cézanne

Paul Cézanne (/seɪˈzæn/ say-ZAN, also UK: /sɪˈzæn/ siz-AN, US: /seɪˈzɑːn/ say-ZAHN,[1][2] French: [pɔl sezan]; 19 January 1839 – 22 October 1906) was a French artist and Post-Impressionist painter whose work laid the foundations of the transition from the 19th-century conception of artistic endeavor to a new and radically different world of art in the 20th century.

Paul Cézanne | |

|---|---|

Paul Cézanne, c. 1861 | |

| Born | 19 January 1839 Aix-en-Provence, France |

| Died | 22 October 1906 (aged 67) Aix-en-Provence, France |

| Resting place | Saint-Pierre Cemetery |

| Nationality | French |

| Education | Académie Suisse, Aix-Marseille University |

| Known for | Painting |

Notable work | Mont Sainte-Victoire seen from Bellevue (c. 1885) Apothéose de Delacroix (1890–1894) Rideau, Cruchon et Compotier (1893–94) The Card Players (1890–1895) The Bathers (1898–1905) |

| Movement | Impressionism, Post-Impressionism |

| Awards | Cézanne medal |

Cézanne is said to have formed the bridge between late 19th-century Impressionism and the early 20th century's new line of artistic enquiry, Cubism. Cézanne's often repetitive, exploratory brushstrokes are highly characteristic and clearly recognizable. He used planes of colour and small brushstrokes that build up to form complex fields. The paintings convey Cézanne's intense study of his subjects. Both Matisse and Picasso are said to have remarked that Cézanne "is the father of us all".

Life and work

Early years and family

The Cézannes came from the commune of Saint-Sauveur (Hautes-Alpes, Occitania). Paul Cézanne was born on 19 January 1839 in Aix-en-Provence.[3] On 22 February, he was baptized in the Église de la Madeleine, with his grandmother and uncle Louis as godparents,[3][4][5][6] and became a devout Catholic later in life.[7] His father, Louis Auguste Cézanne (1798–1886),[8] a native of Saint-Zacharie (Var),[9] was the co-founder of a banking firm (Banque Cézanne et Cabassol) that prospered throughout the artist's life, affording him financial security that was unavailable to most of his contemporaries and eventually resulting in a large inheritance.[10]

.jpg)

His mother, Anne Elisabeth Honorine Aubert (1814–1897),[11] was "vivacious and romantic, but quick to take offence".[12] It was from her that Cézanne got his conception and vision of life.[12] He also had two younger sisters, Marie and Rose, with whom he went to a primary school every day.[3][13]

At the age of ten Cézanne entered the Saint Joseph school in Aix.[14] In 1852 Cézanne entered the Collège Bourbon in Aix[15] (now Collège Mignet), where he became friends with Émile Zola, who was in a less advanced class,[10][13] as well as Baptistin Baille—three friends who came to be known as "Les Trois Inséparables" (The Three Inseparables).[16] He stayed there for six years, though in the last two years he was a day scholar.[17] In 1857, he began attending the Free Municipal School of Drawing in Aix, where he studied drawing under Joseph Gibert, a Spanish monk.[18] From 1858 to 1861, complying with his father's wishes, Cézanne attended the law school of the University of Aix, while also receiving drawing lessons.[19]

Going against the objections of his banker father, he committed himself to pursue his artistic development and left Aix for Paris in 1861. He was strongly encouraged to make this decision by Zola, who was already living in the capital at the time. Eventually, his father reconciled with Cézanne and supported his choice of career. Cézanne later received an inheritance of 400,000 francs from his father, which rid him of all financial worries.[20]

Artistic style

%2C_60_x_73_cm%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_Courtauld_Institute_of_Art%2C_London.jpg)

In Paris, Cézanne met the Impressionist Camille Pissarro. Initially the friendship formed in the mid-1860s between Pissarro and Cézanne was that of master and disciple, in which Pissarro exerted a formative influence on the younger artist. Over the course of the following decade their landscape painting excursions together, in Louveciennes and Pontoise, led to a collaborative working relationship between equals.

Cézanne's early work is often concerned with the figure in the landscape and includes many paintings of groups of large, heavy figures in the landscape, imaginatively painted. Later in his career, he became more interested in working from direct observation and gradually developed a light, airy painting style. Nevertheless, in Cézanne's mature work there is the development of a solidified, almost architectural style of painting. Throughout his life he struggled to develop an authentic observation of the seen world by the most accurate method of representing it in paint that he could find. To this end, he structurally ordered whatever he perceived into simple forms and colour planes. His statement "I want to make of impressionism something solid and lasting like the art in the museums",[21] and his contention that he was recreating Poussin "after nature" underscored his desire to unite observation of nature with the permanence of classical composition.

Optical phenomena

Cézanne was interested in the simplification of naturally occurring forms to their geometric essentials: he wanted to "treat nature in terms of the cylinder, the sphere and the cone"[22] (a tree trunk may be conceived of as a cylinder, an apple or orange a sphere, for example). Additionally, Cézanne's desire to capture the truth of perception led him to explore binocular vision graphically, rendering slightly different, yet simultaneous visual perceptions of the same phenomena to provide the viewer with an aesthetic experience of depth different from those of earlier ideals of perspective, in particular single-point perspective. His interest in new ways of modelling space and volume derived from the stereoscopy obsession of his era and from reading Hippolyte Taine’s Berkelean theory of spatial perception.[23][24] Cézanne's innovations have prompted critics to suggest such varied explanations as sick retinas,[25] pure vision,[26] and the influence of the steam railway.[27]

Exhibitions and subjects

Cézanne's paintings were shown in the first exhibition of the Salon des Refusés in 1863, which displayed works not accepted by the jury of the official Paris Salon. The Salon rejected Cézanne's submissions every year from 1864 to 1869. He continued to submit works to the Salon until 1882. In that year, through the intervention of fellow artist Antoine Guillemet, he exhibited Portrait de M. L. A., probably Portrait of Louis-Auguste Cézanne, The Artist's Father, Reading "L'Événement", 1866 (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.),[28] his first and last successful submission to the Salon.[29][30]

Before 1895 Cézanne exhibited twice with the Impressionists (at the first Impressionist exhibition in 1874 and the third Impressionist exhibition in 1877). In later years a few individual paintings were shown at various venues, until 1895, when the Parisian dealer, Ambroise Vollard, gave the artist his first solo exhibition. Despite the increasing public recognition and financial success, Cézanne chose to work in increasing artistic isolation, usually painting in the south of France, in his beloved Provence, far from Paris.

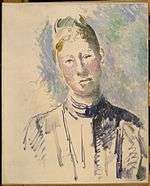

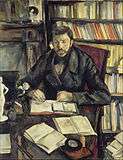

He concentrated on a few subjects and was equally proficient in each of these genres: still lifes, portraits, landscapes and studies of bathers. For the last, Cézanne was compelled to design from his imagination, due to a lack of available nude models. Like the landscapes, his portraits were drawn from that which was familiar, so that not only his wife and son but local peasants, children and his art dealer served as subjects. His still lifes are at once decorative in design, painted with thick, flat surfaces, yet with a weight reminiscent of Gustave Courbet. The 'props' for his works are still to be found, as he left them, in his studio (atelier), in the suburbs of modern Aix.

Cézanne's paintings were not well received among the petty bourgeoisie of Aix. In 1903 Henri Rochefort visited the auction of paintings that had been in Zola's possession and published on 9 March 1903 in L'Intransigeant a highly critical article entitled "Love for the Ugly".[31] Rochefort describes how spectators had supposedly experienced laughing fits, when seeing the paintings of "an ultra-impressionist named Cézanne".[31] The public in Aix was outraged, and for many days, copies of L'Intransigeant appeared on Cézanne's door-mat with messages asking him to leave the town "he was dishonouring".[32]

Death

One day, Cézanne was caught in a storm while working in the field.[33] After working for two hours he decided to go home; but on the way he collapsed. He was taken home by a passing driver.[33] His old housekeeper rubbed his arms and legs to restore the circulation; as a result, he regained consciousness.[33] On the following day, he intended to continue working, but later on he fainted; the model with whom he was working called for help; he was put to bed, and he never left it.[33] He died a few days later, on 22 October 1906[33] of pneumonia and was buried at the Saint-Pierre Cemetery in his hometown of Aix-en-Provence.[34]

Main periods of Cézanne's work

Various periods in the work and life of Cézanne have been defined.[35]

Dark period, Paris, 1861–1870

In 1863 Napoleon III created by decree the Salon des Refusés, at which paintings rejected for display at the Salon of the Académie des Beaux-Arts were to be displayed. The artists of the refused works included the young Impressionists, who were considered revolutionary. Cézanne was influenced by their style but his social relations with them were inept—he seemed rude, shy, angry, and given to depression. His works of this period[36] are characterized by dark colours and the heavy use of black. They differ sharply from his earlier watercolours and sketches at the École Spéciale de dessin at Aix-en-Provence in 1859, and their violence of expression is in contrast to his subsequent works.[37]

In 1866–67, inspired by the example of Courbet, Cézanne painted a series of paintings with a palette knife. He later called these works, mostly portraits, une couillarde ("a coarse word for ostentatious virility").[38] Lawrence Gowing has written that Cézanne's palette knife phase "was not only the invention of modern expressionism, although it was incidentally that; the idea of art as emotional ejaculation made its first appearance at this moment".[38]

Among the couillarde paintings are a series of portraits of his uncle Dominique in which Cézanne achieved a style that "was as unified as Impressionism was fragmentary".[39] Later works of the dark period include several erotic or violent subjects, such as Women Dressing (c. 1867), The Rape (c. 1867), and The Murder (c. 1867–68), which depicts a man stabbing a woman who is held down by his female accomplice.[40]

Impressionist period, Provence and Paris, 1870–1878

After the start of the Franco-Prussian War in July 1870, Cézanne and his mistress, Marie-Hortense Fiquet, left Paris for L'Estaque, near Marseille, where he changed themes to predominantly landscapes. He was declared a draft dodger in January 1871, but the war ended the next month, in February, and the couple moved back to Paris, in the summer of 1871. After the birth of their son Paul in January 1872, in Paris, they moved to Auvers in Val-d'Oise near Paris. Cézanne's mother was kept a party to family events, but his father was not informed of Hortense for fear of risking his wrath. The artist received from his father a monthly allowance of 100 francs.[41]

Camille Pissarro lived in Pontoise. There and in Auvers he and Cézanne painted landscapes together. For a long time afterwards, Cézanne described himself as Pissarro's pupil, referring to him as "God the Father", as well as saying: "We all stem from Pissarro."[42] Under Pissarro's influence Cézanne began to abandon dark colours and his canvases grew much brighter.[43]

Leaving Hortense in the Marseille region, Cézanne moved between Paris and Provence, exhibiting in the first (1874) and third Impressionist shows (1877). In 1875, he attracted the attention of the collector Victor Chocquet, whose commissions provided some financial relief. But Cézanne's exhibited paintings attracted hilarity, outrage, and sarcasm. Reviewer Louis Leroy said of Cézanne's portrait of Chocquet: "This peculiar looking head, the colour of an old boot might give [a pregnant woman] a shock and cause yellow fever in the fruit of her womb before its entry into the world."[44]

In March 1878, Cézanne's father found out about Hortense and threatened to cut Cézanne off financially, but, in September, he relented and decided to give him 400 francs for his family. Cézanne continued to migrate between the Paris region and Provence until Louis-Auguste had a studio built for him at his home, Bastide du Jas de Bouffan, in the early 1880s. This was on the upper floor, and an enlarged window was provided, allowing in the northern light but interrupting the line of the eaves; this feature remains. Cézanne stabilized his residence in L'Estaque. He painted with Renoir there in 1882 and visited Renoir and Monet in 1883.[45]

Mature period, Provence, 1878–1890

In the early 1880s the Cézanne family stabilized their residence in Provence where they remained, except for brief sojourns abroad, from then on. The move reflects a new independence from the Paris-centered impressionists and a marked preference for the south, Cézanne's native soil. Hortense's brother had a house within view of Montagne Sainte-Victoire at Estaque. A run of paintings of this mountain from 1880 to 1883 and others of Gardanne from 1885 to 1888 are sometimes known as "the Constructive Period".[46]

The year 1886 was a turning point for the family. Cézanne married Hortense. In that year also, Cézanne's father died, leaving him the estate purchased in 1859; he was 47. By 1888 the family was in the former manor, Jas de Bouffan, a substantial house and grounds with outbuildings, which afforded a new-found comfort. This house, with much-reduced grounds, is now owned by the city and is open to the public on a restricted basis.[47]

For many years it was believed that Cézanne broke off his friendship with Émile Zola, after the latter used him, in large part, as the basis for the unsuccessful and ultimately tragic fictitious artist Claude Lantier, in the novel L'Œuvre.[48]

Recently letters have been discovered that refute this. A letter from 1887 demonstrates that their friendship did endure for at least some time after.[49][50]

Final period, Provence, 1890–1906

Cézanne's idyllic period at Jas de Bouffan was temporary. From 1890 until his death he was beset by troubling events and he withdrew further into his painting, spending long periods as a virtual recluse. His paintings became well-known and sought after and he was the object of respect from a new generation of painters.[47]

The problems began with the onset of diabetes in 1890, destabilizing his personality to the point where relationships with others were again strained. He traveled in Switzerland, with Hortense and his son, perhaps hoping to restore their relationship. Cézanne, however, returned to Provence to live; Hortense and Paul junior, to Paris. Financial need prompted Hortense's return to Provence but in separate living quarters. Cézanne moved in with his mother and sister. In 1891 he turned to Catholicism.[51]

Cézanne alternated between painting at Jas de Bouffan and in the Paris region, as before. In 1895, he made a germinal visit to Bibémus Quarries and climbed Montagne Sainte-Victoire. The labyrinthine landscape of the quarries must have struck a note, as he rented a cabin there in 1897 and painted extensively from it. The shapes are believed to have inspired the embryonic "Cubist" style. Also in that year, his mother died, an upsetting event but one which made reconciliation with his wife possible. He sold the empty nest at Jas de Bouffan and rented a place on Rue Boulegon, where he built a studio.[47]

The relationship, however, continued to be stormy. He needed a place to be by himself. In 1901 he bought some land along the Chemin des Lauves, an isolated road on some high ground at Aix, and commissioned a studio to be built there (now open to the public). He moved there in 1903. Meanwhile, in 1902, he had drafted a will excluding his wife from his estate and leaving everything to his son. The relationship was apparently off again; she is said to have burned the mementos of his mother.[52]

_in_a_Red_Dress%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_116.5_x_89.5_cm%2C_The_Metropolitan_Museum_of_Art%2C_New_York.jpg)

From 1903 to the end of his life he painted in his studio, working for a month in 1904 with Émile Bernard, who stayed as a house guest. After his death it became a monument, Atelier Paul Cézanne, or les Lauves.[52]

"Cézanne's Doubt": essay by Maurice Merleau-Ponty

Cézanne's stylistic approaches and beliefs regarding how to paint were analyzed and written about by the French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty who is primarily known for his association with phenomenology and existentialism.[53] In his 1945 essay entitled "Cézanne's Doubt", Merleau-Ponty discusses how Cézanne gave up classic artistic elements such as pictorial arrangements, single view perspectives, and outlines that enclosed color in an attempt to get a "lived perspective" by capturing all the complexities that an eye observes. He wanted to see and sense the objects he was painting, rather than think about them. Ultimately, he wanted to get to the point where "sight" was also "touch". He would take hours sometimes to put down a single stroke because each stroke needed to contain "the air, the light, the object, the composition, the character, the outline, and the style". A still life might have taken Cézanne one hundred working sessions while a portrait took him around one hundred and fifty sessions. Cèzanne believed that while he was painting, he was capturing a moment in time, that once passed, could not come back. The atmosphere surrounding what he was painting was a part of the sensational reality he was painting. Cèzanne claimed: "Art is a personal apperception, which I embody in sensations and which I ask the understanding to organize into a painting."[54]

Legacy

Cézanne's works were rejected numerous times by the official Salon in Paris and ridiculed by art critics when exhibited with the Impressionists. Yet during his lifetime Cézanne was considered a master by younger artists who visited his studio in Aix.[55]

Along with the work of Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin, the work of Cézanne, with its sense of immediacy and incompletion, critically influenced Matisse and others prior to Fauvism and Expressionism.[56][57] After Cézanne died in 1906, his paintings were exhibited in a large museum-like retrospective in Paris, September 1907. The 1907 Cézanne retrospective at the Salon d'Automne greatly affected the direction that the avant-garde in Paris took, lending credence to his position as one of the most influential artists of the 19th century and to the advent of Cubism.

Inspired by Cézanne, Albert Gleizes and Jean Metzinger wrote:

Cézanne is one of the greatest of those who changed the course of art history . . . From him we have learned that to alter the coloring of an object is to alter its structure. His work proves without doubt that painting is not—or not any longer—the art of imitating an object by lines and colors, but of giving plastic [solid, but alterable] form to our nature. (Du "Cubisme", 1912)[55][58]

Ernest Hemingway compared his writing to Cézanne’s landscapes.[59][60] As he describes in A Moveable Feast, I was "learning something from the painting of Cezanne that made writing simple true sentences far from enough to make the stories have the dimensions that I was trying to put in them."

Cézanne's explorations of geometric simplification and optical phenomena inspired Picasso, Braque, Metzinger, Gleizes, Gris and others to experiment with ever more complex views of the same subject and eventually to the fracturing of form. Cézanne thus sparked one of the most revolutionary areas of artistic enquiry of the 20th century, one which was to affect profoundly the development of modern art. Picasso referred to Cézanne as "the father of us all" and claimed him as "my one and only master!" Other painters such as Edgar Degas, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Paul Gauguin, Kasimir Malevich, Georges Rouault, Paul Klee, and Henri Matisse acknowledged Cézanne's genius.[55]

Cézanne's painting The Boy in the Red Vest was stolen from a Swiss museum in 2008. It was recovered in a Serbian police raid in 2012.[61]

The 2016 film Cézanne and I explores the friendship between the artist and Émile Zola.[62]

Art market

On 10 May 1999, Cézanne's painting Rideau, Cruchon et Compotier sold for $60.5 million, the fourth-highest price paid for a painting up to that time. As of 2006, it was the most expensive still life ever sold at an auction. One of Cézanne's The Card Players was sold in 2011 to the Royal Family of Qatar for a price variously estimated at between $250 million ($284.1 million today) and possibly as high as $300 million ($341 million today), either price signifying a new mark for highest price for a painting up to that date. The record price was surpassed in November 2017 by Leonardo da Vinci's Salvator Mundi.[63][64]

Gallery

Paintings

The Black Marble Clock

The Black Marble Clock

1869–1871

.jpg)

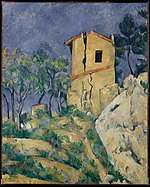

L'Estaque

L'Estaque

1883–1885 Houses in Provence: The Riaux Valley near L'Estaque

Houses in Provence: The Riaux Valley near L'Estaque

1883 The Bay of Marseilles, view from L'Estaque

The Bay of Marseilles, view from L'Estaque

1885

The Neighborhood of Jas de Bouffan

The Neighborhood of Jas de Bouffan

1885-1887

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Thannhauser Collection%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_102_x_81_cm%2C_Pushkin_Museum.jpg)

Mont Sainte-Victoire and Château Noir

Mont Sainte-Victoire and Château Noir

1904–05

Bridgestone Museum of Art, Tokyo, Japan_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

Still life paintings

Watercolours

Boy with Red Vest

Boy with Red Vest

1890 Self-portrait

Self-portrait

1895 Three Pears, ca. 1888–1890, Henry and Rose Pearlman Collection on long-term loan to the Princeton University Art Museum

Three Pears, ca. 1888–1890, Henry and Rose Pearlman Collection on long-term loan to the Princeton University Art Museum Pine Tree in Front of the Caves above Château Noir, ca. 1900, Princeton University Art Museum

Pine Tree in Front of the Caves above Château Noir, ca. 1900, Princeton University Art Museum Mill at the River

Mill at the River

1900–1906 Study of a Skull, 1902–1904, Henry and Rose Pearlman Collection on long-term loan to the Princeton University Art Museum

Study of a Skull, 1902–1904, Henry and Rose Pearlman Collection on long-term loan to the Princeton University Art Museum Still Life with Carafe, Bottle, and Fruit, 1906, Henry and Rose Pearlman Collection on long-term loan to the Princeton University Art Museum

Still Life with Carafe, Bottle, and Fruit, 1906, Henry and Rose Pearlman Collection on long-term loan to the Princeton University Art Museum

Portraits and self-portraits

Portrait of Victor Chocquet

Portrait of Victor Chocquet

1876–77

See also

Notes

- Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- Jones, Daniel (2011). Roach, Peter; Setter, Jane; Esling, John (eds.). Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-15255-6.

- J. Lindsay Cézanne; his life and art, p. 6

- Dominique Auzias, Le Petit Futé, 2008 p. 142 Archived 10 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Dominique Auzias, Jean-Paul Labourdette, Aix-en-Provence 2012, Le Petit Futé, 2012, p. 299 Archived 8 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Olivier-René Veillon, Seul comme Cézanne, Maisonneuve et Larose, 1995, p. 24.

- "Paul Cezanne". TotallyHistory. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- "Louis Auguste Cézanne". Guarda-Mor, Edição de Publicações Multimédia Lda. Archived from the original on 29 March 2007. Retrieved 27 February 2007.

- Danchev, Alex (2012). Cézanne: A Life. Pantheon. p. 45. ISBN 0307377075.

- "Paul Cézanne Biography (1839–1906)". Biography.com. Archived from the original on 3 September 2011. Retrieved 17 February 2007.

- "Louis Auguste Cézanne". Guarda-Mor, Edição de Publicações Multimédia Lda. Archived from the original on 29 March 2007. Retrieved 27 February 2007.

- A. Vollard First Impressions, p. 16

- A. Vollard, First Impressions, p. 14

- P. Machotka Narration and Vision, p. 9

- "Paul Cézanne | French artist". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 17 August 2018. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- "National Gallery of Art timeline, retrieved February 11, 2009". Nga.gov. Archived from the original on 5 November 2010. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- J. Lindsay Cézanne; his life and art, p. 12

- Gowing 1988, p. 215

- P. Cézanne Paul Cézanne, letters, p. 10

- J. Lindsay Cézanne; his life and art, p. 232

- Paul Cézanne, Letters, edited by John Rewald, 1984.

- Cézanne, Paul (2013). The Letters of Paul Cézanne. Translated by Danchev, Alex. Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum. p. 334.

- Rod Bantjes, ‘"Perspectives bâtardes": Stereoscopy, Cézanne, and the Metapictoral Logic of Spatial Construction’, History of Photography, 41:3 (August 2017), 262–285.

- Jon Kear, Paul Cézanne Archived 27 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Reaktion Books, 15 June 2016, p. 65

- Joris-Karl Huysmans, "Trois peintres: Cézanne, Tissot, Wagner," La Cravache, 4 August 1888.

- Hans Sedlmayr, Art in Crisis: The Lost Center, London, 1957. (original German 1948)

- "Cezanne and the Steam Railway (1)". Tomoki Akimaru (Art Historian). Archived from the original on 9 September 2017. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- "The Artist's Father, Reading "L'Événement", 1866, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C". Archived from the original on 26 April 2015. Retrieved 9 August 2015.

- Gowing 1988, p. 110

- "Société des artistes français, catalogue illustré, Salon 1882, Cézanne, Portrait de M. L. A., p. 32, no. 520". Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- Rochefort, Henri, L'Amour du laid, L'Intransigeant Archived 19 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Numéro 8272, 9 March 1903, Gallica, Bibliothèque nationale de France (French)

- The Unknown Matisse: A Life of Henri Matisse. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- Vollard, pp. 113–114

- "Paul Cézanne 1839–1906". MyStudios.com. Archived from the original on 24 March 2007. Retrieved 18 February 2007.

- The scheme presented here is essentially that of the Encyclopædia Britannica. Some alternative names are mentioned. On the whole the various classifications tend to converge.

- It is sometimes called "the Romantic Period", but Cézanne was not primarily interested in Romanticism. The term here refers to personal disposition, rather than connection with a historical movement.

- Le Moniteur, 24 April 1863, in Maneglier, Hervé, Paris Impérial – La vie quotidienne sous le Second Empire, p. 173

- Gowing 1988, p. 10.

- Gowing 1988, p. 104.

- André Dombrowski, Cézanne, Murder, and Modern Life Archived 24 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine, University of California Press, 2013, ISBN 0520273397

- "Cézanne in Provence: A Provençal Chronology of Cézanne: 1870–1879" Archived 22 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine, National Gallery of Art. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- Brion 1974, p. 26

- Rosenblum 1989, p. 348

- Brion 1974, p. 34

- "Cézanne in Provence: A Provençal Chronology of Cézanne: 1880–1889" Archived 15 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine, National Gallery of Art. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- Anne Distel, Michel Hoog, Charles S. Moffett, Impressionism: A Centenary Exhibition, Metropolitan Museum of Art Archived 30 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine, 12 December 1974 – 10 February 1975, p. 56, ISBN 0870990977

- Ulrike Becks-Malorny, Cézanne Archived 1 January 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Taschen, 2001, p. 48, ISBN 3822856428

- "Paul Cézanne, Claude Lantier and Artistic Impotence, by Aruna D'Souza". Archived from the original on 18 January 2018. Retrieved 17 January 2018.

- Elderfield, John; Morton, Mary; Rey, Xavier; Danchev, Alex; Warman, Jayne S. (2017). Cézanne Portraits. London: National Portrait Gallery. p. 224. ISBN 9781855147317. OCLC 1006293797.

- Lethbridge, Robert (Winter 2014). "The End of the Affair: Zola and Cézanne". French Studies Bulletin. 35 (133): 95–99. doi:10.1093/frebul/ktu026.

- Susan Sidlauskas, Cézanne's Other: The Portraits of Hortense Archived 28 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine, University of California Press, 2009, p. 240, ISBN 0520257456

- Dita Amory, et al, Madame Cézanne Archived 28 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2014, p. 19, ISBN 0300208103

- "Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1908—1961)". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Iep.utm.edu. Archived from the original on 25 August 2011.

- Merleau-Ponty 1965

- Philadelphia Museum of Art. "Philadelphia Museum of Art". philamuseum.org. Archived from the original on 14 November 2013.

- Richard Shiff, Cézanne and the End of Impressionism: A Study of the Theory, Technique, and Critical Evaluation of Modern Art, University of Chicago Press, 2014, pp. 55–61, ISBN 022623777X

- "Paul Cézanne Overview and Analysis". The Art Story. Archived from the original on 17 August 2018. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- Albert Gleizes, Jean Metzinger, Du "Cubisme", Edition Figuière, Paris, 1912 (First English edition: Cubism, T. Fisher Unwin, London, 1913)

- Johnson, Kenneth (1984). "Hemingway and Cézanne: Doing the Country". American Literature. 56: 28–37.

- Herlihy, Jeffrey (2011). In Paris or Paname: Hemingway's Expatriate Nationalism. Amsterdam: Rodopi/Brill. p. 61.

- "Serb police find stolen Cezanne painting". CBS News. 12 April 2012. Archived from the original on 9 May 2012. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- Pacatte, Rose. "Film dramatizes broken friendship of Cezanne and Zola". National Catholic Reporter. The National Catholic Reporter Publishing Company. Archived from the original on 24 February 2019. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- Art Media Agency (AMA), 250 M$, a new record for a painting? Archived 23 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine, 4 May 2011

- Haigney, Sophie (3 July 2017). "Lawsuit Reveals Gauguin Painting Was Not World's Most Expensive". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 4 July 2017. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- "Woman with a Coffeepot". www.musee-orsay.fr. Archived from the original on 19 February 2015.

References

- Brion, Marcel (1974). Cézanne. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-86004-1.

- Chun, Young-Paik (2006). "Melancholia and Cézanne's Portraits: Faces beyond the mirror". In Griselda Pollock (ed.). Psychoanalysis and the Image. Routledge. ISBN 1-4051-3461-5.

- Cézanne, Paul; John Rewald; Émile Zola; Marguerite Kay (1941). Paul Cézanne, letters. B. Cassirer. ISBN 0-87817-276-9. OCLC 1196743.

- Danchev, Alex (2012). Cézanne: A Life. Profile Books (UK); Pantheon (US). ISBN 978-1846681653.

- Gowing, Lawrence; Adriani, Götz; Krumrine, Mary Louise; Lewis, Mary Tompkins; Patin, Sylvie; Rewald, John (1988). Cézanne: The Early Years 1859–1872. Harry N. Abrams.

- Lehrer, Jonah (2007). "Paul Cézanne, The Process of Sight". In Jonah Lehrer (ed.). Proust Was a Neuroscientist. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-618-62010-4.

- Klingsor, Tristan (1923). Cézanne. Paris: Rieder.

- Lindsay, Jack (1969). Cézanne: His Life and Art. United States: New York Graphic Society. ISBN 0-8212-0340-1. OCLC 18027.

- Machotka, Pavel (1996). Cézanne: Landscape into Art. United States: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-06701-1. OCLC 34558348.

- Pissarro, Joachim (2005). Cézanne & Pissarro Pioneering Modern Painting: 1865–1885. The Museum of Modern Art. ISBN 0-87070-184-3.

- Rosenblum, Robert (1989). Paintings in the Musée d'Orsay. New York: Stewart, Tabori & Chang. ISBN 1-55670-099-7.

- Vollard, Ambroise (1984). Cézanne. England: Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-24729-5. OCLC 10725645.

Further reading

- Danchev, Alex (2012) Paul Cézanne: A Life, New York: Pantheon, ISBN 978-0-30737-707-4

- Danchev, Alex (2013) The Letters of Paul Cézanne, Los Angeles: Getty Publications, ISBN 978-1-60606-160-2

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Paul Cézanne. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Paul Cézanne |

- National Gallery of Art, Cézanne in Provence

- Paul Cézanne at the Museum of Modern Art

- Getty Research Institute. Los Angeles, California

- Impressionism: A Centenary Exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art – Exhibition catalog: Cézanne (pp. 49–63)

- The Private Collection of Edgar Degas, fully digitized text from The Metropolitan Museum of Art libraries (see Degas and Cézanne: Savagery and Refinement, pp. 197–220)