Ceratium

The genus Ceratium is restricted to a small number (about 7) of freshwater dinoflagellate species. Previously the genus contained also a large number of marine dinoflagellate species. However, these marine species have now been assigned to a new genus called Tripos.[1] Ceratium dinoflagellates are characterized by their armored plates, two flagella, and horns.[2] They are found worldwide and are of concern due to their blooms.

| Ceratium | |

|---|---|

| |

| Ceratium tripos | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Ceratium |

| Species | |

| |

Taxonomy

The genus was originally published in 1793 by Shrank, F. von Paula.[3] The taxonomy of Ceratium varies among several sources. One source states the taxonomy as: Kingdom Chromista, Phylum Miozoa, Class Dinophyceae, Order Gonyaulacales, and Family Ceratiaceae.[3] Another source lists the taxonomy as Kingdom Protozoa, Phylum Dinoflagellata, Class Dinophyceae, Order Gonyaulacales, and Family Ceratiaceae.[4] The taxonomic information listed on the right includes Kingdom Chromalveolate. Thus, sources disagree on the higher levels of classification, but agree on lower levels.

Appearance

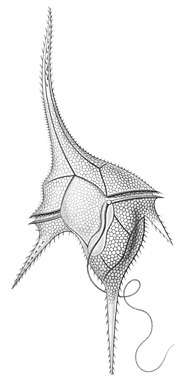

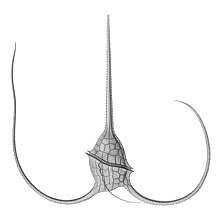

Ceratium species belong to the group of dinoflagellates known as dinophysiales, meaning they contain armored plates.[2] They contain a pellicle, which is a shell, that is made from the cell membrane and vesicles; vesicles are composed of cross-linked cellulose, forming the plates.[2] The pellicle divides into two structures known as the epicone and hypocone that lie above and below the transverse groove, the cingulum, respectively.[2] Two rows of plates surround the epicone and hypocone in a particular pattern that may be inherited by offspring.[2] These patterns may be used to identify groups of dinoflagellates or even species of Ceratium.[2]

The plates contain expanded horns, which is a characteristic feature of Ceratium species.[2] Species tend to have different shaped horns depending whether they are freshwater or marine species.[5] Their morphology depends on the temperature and salinity of the surrounding environment.[6] Species can be identified based on the shape of their horns. For instance, the species Ceratium tripos has horns that are U-shaped.[6]

Species of Ceratium contain two flagella of different lengths that are orientated in the transverse and longitudinal positions.[7] The transverse flagellum is structurally complex and wraps around the cingulum.[2] The movement of the flagellum is described as "wave-like" and allows the organism to spin as it swims.[2] The longitudinal flagellum extends from a groove known as the sulcus, and this flagellum is simpler in structure than the transverse flagellum.[2] The movement of this flagellum pulls the organism forward, but ultimately its movement is controlled by the viscosity of the water.[2]

Species of Ceratium have other structures called chromatophores, which contain red, brown, and yellow pigments used for photosynthesis.[8]

The average size of a Ceratium dinoflagellate is between 20–200 µm in length, which classifies it as belonging to the microplankton size category.[9]

Life cycle

Reproduction

Ceratiums have zygotic meiosis in their alternation of generation.

Ceratium dinoflagellates may reproduce sexually or asexually.[4] In asexual reproduction, the pellicle (shell) pulls apart and exposes the naked cell.[2] The cell then increases in size and divides, creating 4–8 daughter cells, each with two flagella.[2] The nuclear membrane is present throughout the process and the centrioles are not present, unlike many other eukaryotic organisms.[2] The nuclear membrane only divides when the waist of the organism constricts.[2]

In sexual reproduction, the cells of two organisms couple close to their sulci (longitudinal groove).[2] Meiosis occurs, which allows the chromosomes given by the haploid parents to pair.[2] Then diploid offspring, known as "swarmers", are released.[2]

Growth

Species of Ceratium are mixotrophic, meaning they are both photosynthetic and heterotrophic, consuming other plankton.[4]

Ceratium dinoflagellates have a unique adaptation that allows them to store compounds in a vacuole that they can use for growth when nutrients become unavailable.[10]

They are also known to move actively in the water column to receive maximum sunlight and nutrients for growth.[9] Another adaptation that helps growth includes the ability to extend appendages during the day which contain chloroplasts to absorb light for photosynthesis. At night, these organisms retract these appendages and move to deeper layers of the water column.[11]

Distribution and habitat

Geographic

Species of Ceratium are found across high and low latitudes,[5] but are commonly found in temperate latitudes.[12] Marine species found in warmer tropical seas in lower latitudes tend to have more branched horns than marine species found in the cold waters of higher latitudes.[5] The warm water of the tropics is less viscous, so marine species of Ceratium contain more branched horns in order to remain suspended in the water column.[5] The main function for the horns is to maintain buoyancy.

Seasonal

As lakes and ponds stratify in the summer due to a decrease in mixing, freshwater species of Ceratium tend to dominate the water column.[5]

Ecology

Ceratium sp. are generally considered harmless and produce non-toxic chemicals.[13] Under certain conditions that promote rapid growth of the population, Ceratium sp. blooms known as Red Tides can deplete the resources and nutrients of the surrounding environment.[13] These blooms also deplete the dissolved oxygen in the water, which is known to cause fish kills.[14]

These dinoflagellates play important roles at the base of the food web. They are sources of nutrients for larger organisms and also prey on smaller organisms[13] such as diatoms.[2]

Human use and impact

Worldwide, especially in higher latitudes, the frequency of red tides has increased, which may be due to human impacts on the coasts in terms of pollution.[2] As a result, dead fish from the oxygen-depleted water wash up on beaches, much to the dismay of people at resorts and hotels.[2]

The migration of these species has been impacted by global warming. Because the surface temperature of the ocean rises, these organisms move to deeper layers of the water column as they are temperature sensitive.[15] Due to this behavior, species of Ceratium are used as biological indicators because the deeper they are found in the water column, the greater the impact from global warming.[15]

See also

References

- Gómez, F (2013). "Reinstatement of the dinoflagellate genus Tripos to replace Neoceratium, marine species of Ceratium (Dinophyceae, Alveolata)". Cicimar Oceánides. 28 (1): 1–22.

- Miller, Charles B.; Wheeler, Patricia A. (2012). "2. The phycology of phytoplankton". Biological Oceanography (2nd ed.). Wiley. pp. 39–49. ISBN 978-1-4443-3301-5.

- "Ceratium F.Schrank, 1793". Algaebase. Retrieved 2016-03-14.

- "EOS". Phytoplankton Encyclopedia Project. Retrieved 2016-03-14.

- Reynolds, C.S. (2006). The Ecology of Phytoplankton. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-45489-6.

- Burns, D.A.; Mitchell, J.S. (1982). "Further examples of the dinoflagellates genus Ceratium from New Zealand coastal waters". New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research. 16 (1): 57–67. doi:10.1080/00288330.1982.9515946.

- Reynolds, C.S. (1984). The Ecology of Freshwater Phytoplankton. Cambridge University Press. pp. 99–. ISBN 978-0-521-28222-2.

- "Ceratium. (n.d.)". Encyclopædia Britannica online.

- Pal, Ruma; Choudhury, Avik Kumar (2014). An Introduction to Phytoplanktons: Diversity and Ecology. Springer. ISBN 978-81-322-1838-8.

- Sahu, G.; Mohanty, A.K.; Samantara, M.K.; Satpathy, K.K. (2014). "Seasonality in the distribution of dinoflagellates with special reference to harmful algal species in tropical coastal environment, Bay of Bengal". Environ Monit Assess. 186 (10): 6627–44. doi:10.1007/s10661-014-3878-3. PMID 25012144.

- Sardet, Christian; Ohman, Mark (2015). Plankton: Wonders of the Drifting World. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-18871-3.

- Soderberg, L.M.; Hanson, P.J. (2007). "Growth limitation due to high pH and low inorganic carbon concentrations in temperate species of the dinoflagellates genus Ceratium". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 351: 103–112. doi:10.3354/meps07146. JSTOR 24872109.

- "Ceratium arietinum". www.sahfos.ac.uk. Retrieved 2016-03-13.

- Lim, H.C.; Teng, S.T.; Leaw, C.P.; Iwataki, M.; Lim, P.T. (2014). "Phytoplankton assemblage of the merambong shoal, tebrau straits with note on potentially harmful species". Malayan Nature Journal. 66 (1–2): 198–211. Archived from the original on 2017-09-24. Retrieved 2017-09-24.

- Tunin-Ley, A.; Ibañez, F.; Labat, J.; Zingone, A.; Lemée, R. (2009). "Phytoplankton biodiversity and NW Mediterranean Sea warming: Changes in the dinoflagellates genus Ceratium in the 20th century". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 375: 85–99. doi:10.3354/meps07730. JSTOR 24872971.

External links