Kerameikos

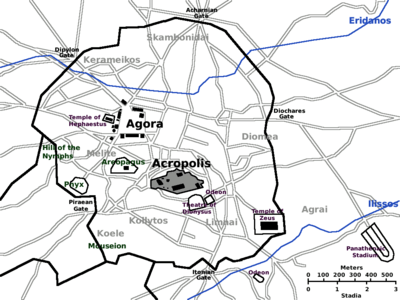

Kerameikos (Greek: Κεραμεικός, pronounced [ce.ɾa.miˈkos]) also known by its Latinized form Ceramicus, is an area of Athens, Greece, located to the northwest of the Acropolis, which includes an extensive area both within and outside the ancient city walls, on both sides of the Dipylon (Δίπυλον) Gate and by the banks of the Eridanos River. It was the potters' quarter of the city, from which the English word "ceramic" is derived, and was also the site of an important cemetery and numerous funerary sculptures erected along the road out of the city towards Eleusis.

Kerameikos Κεραμεικός | |

|---|---|

Neighborhood | |

| |

Location within Athens | |

| Coordinates: 37°58′42″N 23°43′8″E | |

| Country | Greece |

| Region | Attica |

| City | Athens |

| Postal code | 105 53 |

| Area code(s) | 210 |

| Website | www.cityofathens.gr |

History and description

The area took its name from the city square or dēmos (δῆμος) of the Kerameis (Κεραμεῖς, potters), which in turn derived its name from the word κέραμος (kéramos, "pottery clay", from which the English word "ceramic" is derived).[1] The "Inner Kerameikos" was the former "potters' quarter" within the city and "Outer Kerameikos" covers the cemetery and also the Dēmósion Sēma (δημόσιον σῆμα, public graveyard) just outside the city walls, where Pericles delivered his funeral oration in 431 BC. The cemetery was also where the Ηiera Hodos (the Sacred Way, i.e. the road to Eleusis) began, along which the procession moved for the Eleusinian Mysteries. The quarter was located there because of the abundance of clay mud carried over by the Eridanos River.

The area has undergone a number of archaeological excavations in recent years, though the excavated area covers only a small portion of the ancient dēmos. It was originally an area of marshland along the banks of the Eridanos river which was used as a cemetery as long ago as the 3rd millennium BC. It became the site of an organised cemetery from about 1200 BC; numerous cist graves and burial offerings from the period have been discovered by archaeologists. Houses were constructed on the higher drier ground to the south. During the Archaic period increasingly large and complex grave mounds and monuments were built along the south bank of the Eridanos, lining the Sacred Way.[1]

The building of the new city wall in 478 BC, following the Persian sack of Athens in 480 BC, fundamentally changed the appearance of the area. At the suggestion of Themistocles, all of the funerary sculptures were built into the city wall and two large city gates facing north-west were erected in the Kerameikos. The Sacred Way ran through the Sacred Gate, on the southern side, to Eleusis. On the northern side a wide road, the Dromos, ran through the double-arched Dipylon Gate (also known as the Thriasian Gate) and on to the Platonic Academy a few miles away. State graves were built on either side of the Dipylon Gate, for the interment of prominent personages such as notable warriors and statesmen, including Pericles and Cleisthenes.[1]

After the construction of the city wall, the Sacred Way and a forking street known as the Street of the Tombs again became lined with imposing sepulchral monuments belonging to the families of rich Athenians, dating to before the late 4th century BC. The construction of such lavish mausolea was banned by decree in 317 BC, following which only small columns or inscribed square marble blocks were permitted as grave stones. The Roman occupation of Athens led to a resurgence of monument-building, although little is left of them today.[1]

During the Classical period an important public building, the Pompeion, stood inside the walls in the area between the two gates. This served a key function in the procession (pompē, πομπή) in honour of Athena during the Panathenaic Festival. It consisted of a large courtyard surrounded by columns and banquet rooms, where the nobility of Athens would eat the sacrificial meat for the festival. According to ancient Greek sources, a hecatomb (a sacrifice of 100 cows) was carried out for the festival and the people received the meat in the Kerameikos, possibly in the Dipylon courtyard; excavators have found heaps of bones in front of the city wall.[1]

The Pompeion and many other buildings in the vicinity of the Sacred Gate were razed to the ground by the marauding army of the Roman dictator Sulla, during his sacking of Athens in 86 BC; an episode that Plutarch described as a bloodbath. During the 2nd century AD, a storehouse was constructed on the site of the Pompeion, but it was destroyed during the invasion of the Heruli in 267 AD. The ruins became the site of potters' workshops until about 500 AD, when two parallel colonnades were built behind the city gates, overrunning the old city walls. A new Festival Gate was constructed to the east with three entrances leading into the city. This was in turn destroyed in raids by the invading Avars and Slavs at the end of the 6th century, and the Kerameikos fell into obscurity. It was not rediscovered until a Greek worker dug up a stele in April 1863.[1]

Archaeology

_Kerameikos%2C_Ancient_Graveyard%2C_Athens%2C_Greece_(4451627317).jpg)

Archaeological excavations in the Kerameikos began in 1870 under the auspices of the Greek Archaeological Society. They have continued from 1913 to the present day under the German Archaeological Institute at Athens.

During the construction of Kerameikos station for the expanded Athens Metro, a plague pit and approximately 1,000 tombs from the 4th and 5th centuries BC were discovered. The Greek archaeologist Efi Baziotopoulou-Valavani, who excavated the site, has dated the grave to between 430 and 426 BC. Thucydides described the panic caused by the plague, possibly an epidemic of typhoid which struck the besieged city in 430 BC. The epidemic lasted for two years and killed an estimated one third of the population. He wrote that bodies were abandoned in temples and streets, to be subsequently collected and hastily buried. The disease reappeared in the winter of 427 BC.

Latest findings in the Kerameikos include the excavation of a 2.1 m tall Kouros, unearthed by the German Archaeological Institute at Athens under the direction of Professor Wolf-Dietrich Niemeier. This Kouros is the larger twin of the one now kept in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and both were made by the same anonymous sculptor called the "Dipylon Master".

Large areas adjacent to those already excavated remain in to be explored, as they lie under the fabric of modern-day Athens. Expropriation of these areas has been delayed until funding is secured.

Museum

The area is enclosed and visitable through an entrance on the last block of Ermou Street, close to the intersection with Peiraios Street. The Kerameikos Museum is housed there, in a small neoclassical building that houses the most extensive collection of burial-related artifacts in Greece, varying from large-scale marble sculpture to funerary urns, stelae, jewelry, toys etc. The original burial monument sculptures are displayed within the museum, having been replaced by plaster replicas in situ. The museum incorporates inner and outer courtyards, where the larger sculptures are kept. Down the hill from the museum, visitors can wander among the Outer Kerameikos ruins, the Demosion Sema, the banks of the Eridanos where some water still flows, the remains of the Pompeion and the Dipylon Gate, and walk the first blocks of the Sacred Way towards Eleusis and of the Panathenaic Way towards the Acropolis. The bulk of the area lies about 7–10 meters below modern street level, having in the past been inundated by centuries' worth of sediment accumulation from the floods of the Eridanos.

Metro station

As of spring 2007 Keramikos is the name given to the metro station which belongs to Line 3 of the Athens Metro is adjacent to the Technopolis of Gazi.

Notes

- Hans Rupprecht Goette, Athens, Attica and the Megarid: An Archaeological Guide, p. 59

References

- Ursula Knigge: Der Kerameikos von Athen. Führung durch Ausgrabungen und Geschichte. Krene-Verl., Athen 1988.

- Wolf-Dietrich Niemeier: Der Kuros vom Heiligen Tor. Überraschende Neufunde archaischer Skulptur im Kerameikos in Athen. Zabern, Mainz 2002. (Zaberns Bildbände zur Archäologie) ISBN 3-8053-2956-3

- Akten des Internationalen Symposions Die Ausgrabungen im Kerameikos, Bilanz und Perspektiven. Athen, 27.–31. Januar 1999. Zabern, Mainz am Rhein 2001. (Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Athenische Abteilung, 114) ISBN 3-8053-2808-7

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kerameikos. |